Strength and impermeability of cement-based materials containing nano silica-polymer composites

The influence of nano-SiO2 (NS)/styrene-acrylate (SA) latex composites on the strength and impermeability of cementitious materials was studied and the underlying mechanism is discussed on the basis of its effect on the hydration characteristics and microstructures. The results show that the loss of early strength and delay of hydration caused by the SA mix by itself could be significantly improved by the combined addition of SA-NS. This combined addition of SA-NS can also reduce the total pore volume, refine the pore structure, decrease the amount of harmful and more harmful pores and increase the degree of hydration of the cement clinker and the degree of polymerization of the C-S-H gels, thereby improving the strength and impermeability.

1 Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used civil engineering material in the world. Over the years the output of concrete from China has made up more than half the world’s total output. Concrete is a brittle, heterogeneous, material that will inevitably suffer from physical and chemical erosion when it is in service, especially in complex service environments. This may include chloride salt, sulfate, carbonate and water erosion, resulting in a decline in performance or even destruction of the whole structure [1], thus reducing the safety and durability of buildings. These durability...

1 Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used civil engineering material in the world. Over the years the output of concrete from China has made up more than half the world’s total output. Concrete is a brittle, heterogeneous, material that will inevitably suffer from physical and chemical erosion when it is in service, especially in complex service environments. This may include chloride salt, sulfate, carbonate and water erosion, resulting in a decline in performance or even destruction of the whole structure [1], thus reducing the safety and durability of buildings. These durability indices are in fact closely related to the impermeability of the cement matrix composites, so it is very important to study the impermeability of cement-based materials to improve their durability [2, 3].

The addition of polymer can significantly improve the impermeability of cement-based materials. Styrene-acrylate (SA) latex, a common polymer material, has been widely used in cement-based materials due to its many advantages, such as low price, non-toxic side effects, less pollution, good versatility and applicability and the fact that it does not readily ignite or explode. The research of Kong et al. [4] showed that as the cement hydration progresses the polymers and hydration products can form an interwoven organic-inorganic interpenetrating structure, thus improving the properties of cement-based materials. Zhang et al. [5] found that SA could significantly reduce the porosity and improve the compactness of cement-based materials by filling the pores. The research results of Dou et al. [6] confirmed that the filling and sealing by the polymer films can significantly enhance the impermeability of cement-based materials by improving their pore structures and compactness. However, in addition to discussing the advantages of SA in modified cement-based materials, relevant scholars have also pointed out its disadvantages in practical use, of which the most severe is that its incorporation can cause a delay of the cement hydration [7-9]. This results in the loss of early strength of cement-based materials [10, 11], which seriously affects their efficiency in construction work. It is therefore a matter of urgency that the problem of early strength loss caused by incorporation of polymers in practical engineering should be solved in order to improve their usability in construction work.

The early strength of cement-based materials is closely related to their hydration processes and microstructures, so the improvement in early strength can be achieved by promoting the hydration of cement clinker and obtaining uniform and compact microstructures. One of the most popular technologies is currently the incorporation of nanoparticles in cement-based materials. This can induce the cement hydration to produce more and denser C-S-H gels through the crystal nucleation effect, thereby improving the strength. Nano silica (NS) has attracted more and more attention because of its excellent properties. It has been reported in the literature that NS not only possesses good pozzolanic activity and provides seeds for hydration products at the early stages but also acts as a pore filler to modify the microstructure and interface transition zone (ITZ), thereby making the paste more compact. Singh [12], Du [13], Hou [14] and Zhang [15] et al. have pointed out that the effect of NS is to accelerate the early hydration of cement and refine the pore structure, and thus make hardened cement paste denser at the micro-structural level. The study by Zhang et al. [1] showed that NS has a superior ITZ modification ability and can greatly improve the permeability resistance of cement-based materials to chloride ions. It can therefore be expected that SA-NS mixed in with cement-based materials can not only compensate for the early strength decline caused by SA incorporated by itself but also further improve the original density and permeability resistance of cement-based materials. This superimposes and complements the advantages and disadvantages of nanoparticles and polymers.

The effects of SA and NS on the mechanical properties, hydration processes and microstructure of cement-based materials have now been extensively studied but any understanding of the effects of their composites on the properties of cement-based materials is relatively limited. Current researches focusing on nanoparticles and polymer-modified cement-based materials and their composite application are expected to provide new ideas for the development of cementitious materials. The effects of SA and NS composites on the compressive strength and impermeability of cement-based materials were therefore studied and the regulation and control mechanisms were explored and revealed in relation to the hydration products and microstructures. Such results should provide a theoretical basis for the composite application of nanoarticles/polymers in cement-based materials.

2. Experimental

2.1 Raw materials

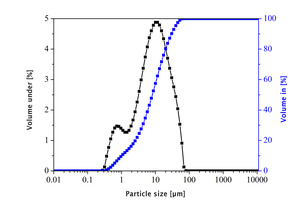

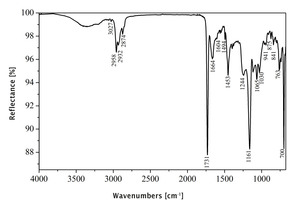

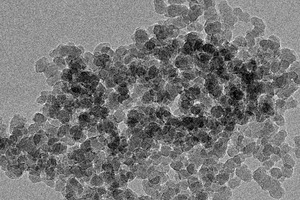

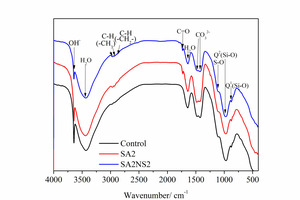

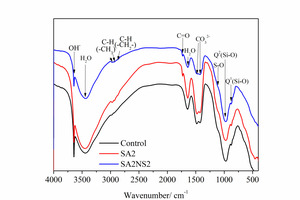

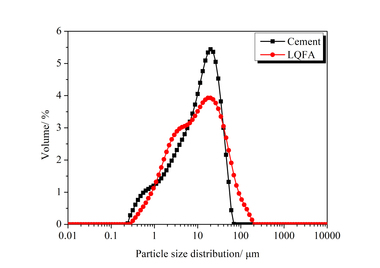

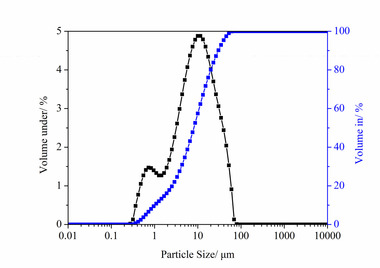

The chemical composition and particle size distribution of P·I 42.5 Portland cement (PC) are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1 respectively. The FT-IR image of styrene-acrylate (SA) latex is shown in Figure 2. The peaks at 2874 cm-1 and 2958 cm-1 in Figure 2 are the areas of –CH3 stretching vibration absorption, the peak at 2932 cm-1 is the area of –CH2 stretching vibration absorption, the peak at 1731 cm-1 is the area of C=O stretching vibration absorption, the peaks at 1494 cm-1 and 1453 cm-1 are the areas of COO- deformation and stretching vibration absorption in acrylic ester, the peaks at 1244 cm-1 and 11161 cm-1 are the areas of -C-O- symmetrical stretching vibration absorption in the ester group, the peaks from 841 cm-1 to 1065 cm-1 are the characteristic areas of butyl ester, the peaks at 1604 cm-1 and 763 cm-1 are the characteristic areas of the benzene ring, 1664 cm-1 is the C=C stretching vibration peak and 699 cm-1 is the C-H out-of-plane bending absorption peak in the benzene ring. The average particle size of the nano silica (NS) powders was about 20 nm and the TEM image is shown in Figure 3. The standard sand used in the specimen as the aggregate meets the ISO 679-2009 standard [16]. Deionized water prepared in-house was used throughout the experiment. A defoamer was used to prevent the formation of large bubbles after the addition of SA. Polycarboxylate superplasticizer (PS) was added to ensure the same fluidity level for the same water/binder ratio.

2.2 Sample preparation and mix design

The mix ratios for mortars are shown in Table 2. The sand-binder ratio, water-binder ratio and polymer-binder ratio were 3, 0.5 and 2% respectively. The NS was considered as a component of the binder, accounting for 2% of the total binder mass. The mortar specimens used for strength testing were prepared in accordance with GB/T17671-1999 [17] and the compressive strengths at 3 d and 28 d were measured after being cured to the specified age in a standard curing chamber with a relative humidity greater than 90% and a temperature of (20±2) °C. The mortar sample used for the chloride ion diffusion coefficient test was prepared in accordance with GB/T 50082-2009 [18].

2.3 Test methods

2.3.1 Compressive strength

The compressive strengths of the samples were tested in accordance with GB/T 17671-1999 [17]. Six specimens were measured for each mix and the average was used as the final result.

2.3.2 Rapid chloride migration (RCM)

The chlorine ion diffusion coefficient was measured by the RCM method in accordance with GB/T 50082-2009 [18] and the results were used to evaluate the impermeability of the cement-based materials.

2.3.3 Pore structure

A mercury intrusion porosimeter (MIP, Quantachrome Autoscan-60) was used to test the pore structure of cement-based materials, in which the surface tension of mercury was 480 mN/m and the contact angle was 140°.

2.3.4 XRD

An X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance) was used at a scanning rate of 8°/min with a step size of 0.02° and a 2-theta range of 5~70° to analyze the sample phases.

2.3.5 FTIR

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, Nexus) spectroscopy technique was used for further investigation of the changes in phase using a wavelength range from 4000 to 400 cm-1.

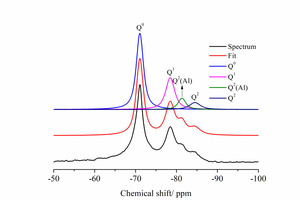

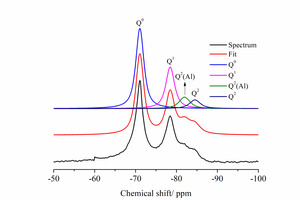

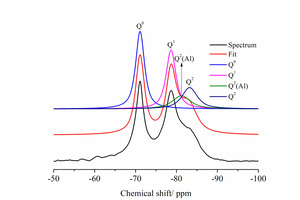

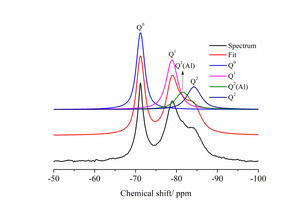

2.3.6 29Si NMR

Magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS-NMR, Bruker Avance III 400) using a 7 mm ZrO2 rotor at a speed of 6.0 kHz was carried out to analyze the composition and structure of 29Si-based substances. The average chain length (ACL) and the degree of cement hydration (aPC) of C-S-H gel were calculated as follows [19-21]:

⇥(1)

⇥(2)

Where I0(Q0) and I(Q0) represent the integral intensities of the Q0 signal before and after cement hydration and I(Q1), I(Q2) and I[Q2(Al)] represent the integral intensities of signals Q1, Q2 and Q2(Al) respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Compressive strength

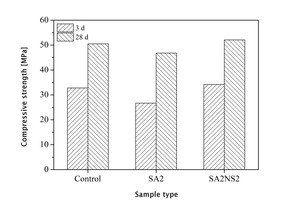

The compressive strengths of three different samples are shown in Figure 4.

As can be seen, the compressive strengths of the samples were significantly reduced when SA was added, mainly because the polymer was adsorbed on the surface of the cement particles and gradually formed a film, which significantly delays cement hydration and ultimately reduces the compressive strength [7-9]. It is also clear that the effect of SA is more significant in the reduction of early strength than with the later strength. Specifically, 2% SA reduced the compressive strength by 18.6% at 3 d and by 7.3% at 28 d. This is mainly because the formation of polymer film was able to retard the evaporation of water from the mortar, which is assists the hydration of clinker with gradually increasing age [4].

If SA is incorporated then the addition of NS can significantly improve the strength of the mortar and compensate for the strength loss caused by using SA by itself. As shown in Figure 4, the compressive strengths at 3 d and 28 d increased by 28.1% and 11.3% respectively after the addition of 2% NS. The NS clearly has a more significant beneficial effect on strength at 3 d than that at 28 d, largely because nanoparticles can provide nucleation sites for hydration products at an early age, which is conducive to the formation of C-S-H gels, coupled with the filling effect of nanoparticles. There was a significant improvement in early strength [12-14].

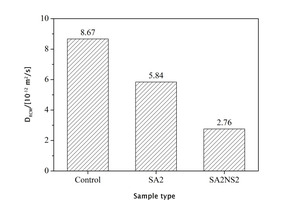

3.2 Chloride ion impermeability

The influence of SA and SA-NS on the chloride diffusion coefficient of mortars is shown in Figure 5. This shows that the control sample has the largest chloride ion diffusion coefficient at 28 d and the addition of SA or SA-NS significantly reduced the diffusion coefficient. The chloride diffusion coefficient of the SA2 sample fell by 32.6% compared with that of the control sample. This indicates that incorporation of the polymer can significantly hinder the diffusion of chloride ions, which is consistent with the results of Liu et al. [11]. This is mainly because the capillary pore plugging effect of the polymer film and polymer particles can block the interlinking of the capillary pores and improve the pore structure of the hardened cement paste [11-13]. Moreover, the addition of 2% NS further reduced the chloride diffusion coefficient, which was 68.2% lower than that of the control sample, indicating that the sample mixed with SA-NS had a good resistance to chloride penetration.

In general, the impermeability of cement-based materials is closely related to the pore structure and hydration behaviour and this will be studied in the following sections.

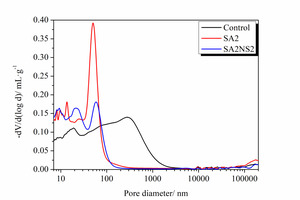

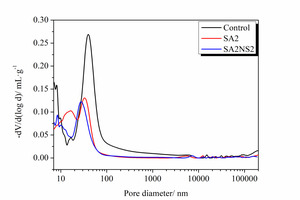

3.3 Pore structure analysis

Porosity is one of the main factors affecting the strength and impermeability of cement-based materials. In general, the greater the density of a cementitious composite, the better is its permeability resistance and the higher is its strength. Wu [22] divided the pores of cement-based materials into four categories according to the different effects of different pore levels on strength, namely harmless pores (< 20 nm), less harmful pores (20-50 nm), harmful pores (50-200 nm) and more harmful pores (> 200 nm). Shen et al. [23] pointed out that when the pore size is less than 10 nm, the ionic permeability coefficient is of an order of magnitude of about 10-14 m2/s, which can be considered as basically impermeable. Mehta et al. [24] found that pores larger than 100 nm have a greater impact on the permeability of cement-based materials. Teramura et al. [25] believed that only the medium pores of 10~50 nm and the large pores of 50~104 nm could significantly affect the properties of cement-based materials, including strength, permeability and durability. At present it is generally believed that pores smaller than 10 nm have almost no influence on the permeability and that pores between 10 nm and 50 nm have little influence on the permeability. Only the interconnected pores larger than 50 nm have a significant influence on the permeability of cement-based materials. In this paper, MIP was used to characterize the influence of SA and NS on the pore structure of cement-based materials. The pore size distributions and structural parameters of each sample at 3 d and 28 d are shown in Figure 6 and Table 3 respectively.

As can be seen from Figure 6a, the addition of 2% SA can reduce the most probable pore (MPA) of the sample from about 300 nm to 50 nm, which indicates that SA has a significant role in refining the pore size. Table 3 (3 d sample) shows that there was a sharp decrease in the pores with a size greater than 50 nm while there was a remarkable increase in the pores smaller than 50 nm when SA was added, which demonstrates that SA can make the pores change from harmful pores and more harmful pores to harmless pores and less harmful pores with the obvious effect of refining the pore structure. There is a slight in increase in MPA and in the total pore volume if NS is also added but there is a distinct decrease in pores larger than 20 nm and a slight increase in pores smaller than 20 nm, which means that NS with a particle size about 20 nm has a significant role in refining the pore structure.

It is clear from Figure 6b and Table 3 that the total pore volume and the MPA of all the samples are lower at 28 d than those at 3 d, mainly because of the gradual formation of C-S-H gels that can fill the pores and make the paste more compact with extended curing time. The total pore volume of samples at 28 d and samples at 3 d also showed a similar change in a descending order of control>SA2>SA2NS2.

These results indicate that the addition of SA and NS can significantly reduce porosity, optimize pore size distribution and improve the density of cement pastes, which contributes to improving the chloride ion permeability resistance of the samples. However, the variations in porosity and pore size distribution cannot fully explain the variations in compressive strength. The addition of NS reduced the porosity and optimized the pore size distribution with a corresponding increase in the sample strength. The addition of SA also reduced the porosity and the amount of harmful and more harmful pores but the sample strength decreased instead of increasing. This is because the strength of cement-based material is not only related to its porosity and pore size distribution but also related to its microstructure, degree of hydration and phase type.

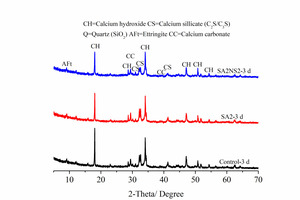

3.4 XRD analysis

The addition of SA and NS will affect the hydration behaviour of cement-based materials, including the hydration process and hydration products. XRD was selected to analyze the hydration products of the sample at 3 d and 28 d, as shown in Figure 7.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that all the hydration samples contain similar phases, principally calcium hydroxide (CH), unhydrated calcium silicates (CS: C2S or C3S), calcium carbonate (CC) and ettringite (AFt). Figure 7a shows that every sample exhibited a strong CS characteristic peak after curing for 3 d due to the low degree of hydration of cement clinker at an early age. When compared with the control sample the characteristic peaks of CH were weakened and those of CS were enhanced by the addition of 2% SA. This is because, firstly, the incorporation of SA can form a dense film on the cement surface, which hinders cement hydration [7-9], resulting in a decrease in cement consumption and CH production and secondly because the SA can react with and consume the CH [4, 11]. This hindrance to hydration by the addition of SA is also one of the reasons for the decrease of sample strength. After the addition of NS there was an obvious weakening of the characteristic peaks of CH and CS, mainly because the pozzolanic activity and nucleation effect of NS can consume a great deal of CH and promote the hydration of cement clinker, which can also explain the increase in the compressive strength of the sample.

As can be seen from Figure 7b, the characteristic peaks of CH and CS of the three samples at 28 d showed a similar trend to those at 3 d, i.e. the addition of SA weakens the CH peak and enhances the CS peak while the addition of NS further weakens the CH peak and the CS peak. However, compared with the 3 d sample, the characteristic peak intensity of CS decreased sharply in all samples, because the CS was gradually consumed with progressing curing time.

From the above analysis it can be seen that the addition of NS can significantly promote the hydration of cement clinker, thus forming a large number of C-S-H gels, which helps to reduce porosity and improve strength.

3.5 FT-IR analysis

The structures of the samples at 3 d and 28 d were characterized by FT-IR, as shown in Figure 8, in order to explore the group characteristics of the hydration products. This shows that a OH- vibration peak related to the hydration product CH appeared at about 3645 cm-1 regardless of whether or not SA was added. The OH- peak decreased significantly after the addition of SA, mainly because the SA was able to form a dense film covering the surface of cement clinker and hinder the cement hydration [7-9]. The reaction between SA and CH is another reason for the decrease in CH. This is consistent with the XRD test results [4, 11].

Q1 and Q2 vibration peaks appear in all samples near 876 cm-1 and 970 cm-1 due to the stretching vibration of the Si-O bond. For the samples mixed with SA the Q1 and Q2 vibration peaks both decreased at the same age, which indicated that the amount of C-S-H gels was reduced after the addition of SA and indirectly confirmed that the incorporation of SA had a certain blocking effect on cement hydration. This is also consistent with the results of XRD analysis.

In contrast to the control sample, new vibration peaks appeared in the samples containing SA. These were the vibration peaks of the C-H bond in -CH3 (around 2933 cm-1 and 2964 cm-1), the C-H bond in -CH2 (around 2870 cm-1) and the C=O group (around 1730 cm-1).

When NS was added there was a clear decrease in the vibration peak intensity related to OH- due to the consumption of CH by the strong pozzolanic activity of NS. The intensities of the vibration peaks of Q1 and Q2 also increased, which indicates that the addition of NS could promote cement hydration and increase the amount of C-S-H gels in cement pastes, and thus improve the compactness and permeability resistance of cement-based materials. This is consistent with the results in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

There was little change in the types of hydration products in the cement pastes from 3 d to 28 d. However, due to the continuous hydration, the vibration peaks of OH- and Si-O increased continuously, indicating an increase in hydration products. This is consistent with the XRD results.

3.6 NMR and SEM analysis

To further illustrate the issues discussed above, 29Si MAS NMR was used to characterize the hydrated pastes, as shown in Figure 9.

Previous studies [19, 21, 26] have confirmed that the Q0 peak related to unhydrated clinker is located at about -71 ppm and the Q1, Q2(Al) and Q3 peaks representing hydration products are located approximately at -79 ppm, -81 ppm and -84 ppm respectively.

Table 4 shows that the degree of cement hydration at 3 d increased from 45.03% to 47.44% with the combined incorporation of 2% SA and 2% NS. This is because active nanoparticles can react with CH and provide seeds for cement hydration [12-14]. The NMR and XRD test results are consistent, and the reason for the strength change caused by the incorporation of SA-NS can be explained to some extent by the changes in the degree of hydration. The influence of SA-NS on compressive strength can also be explained by the change of ACL. In general, the longer the ACL the higher is the degree of polymerization and the greater the strength of the C-S-H gels [21]. The combined addition of SA-NS will lead to an increase in the ACL value, so the strength of the cement-based materials increased accordingly.

The change in aPC and ACL at 28 d showed a similar trend to those at 3 d, i.e. the combined addition of SA and NS increased the degree of hydration and the ACL. However, in comparison with the 3 d sample the degree of hydration increased in all samples because the hydration continued with extending curing time.

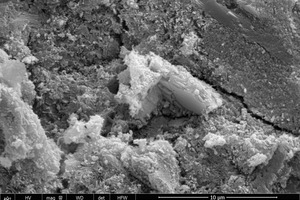

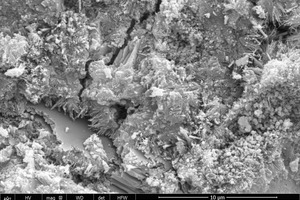

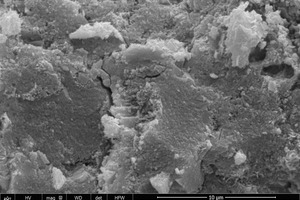

SEM was used to characterize the surface appearance of the hydrates, as shown in Figure 10, so that the morphology of the hydration products could be observed more intuitively.

As can be seen from Figure 10a, the control sample has a loose C-S-H gel structure at 3 d with a large number of pores and there are also some small needle AFt crystals, with poor overall densification. In contrast, the C-S-H gels in the samples modified with SA and NS became finer and denser, with significantly reduced pores and more uniform and compact structure, as shown in Figure 10b. This is due to the filling action of the NS and SA as well as to the function of the NS in promoting the nucleation effect and pozzolanic effect on cement hydration. These can refine the pore structure and thus improve the density of hardened cement.

As shown in Figures 10c and 10d, both the control sample and the SA2NS2 sample at 28 d became more compact than those at 3 d because a large number of C-S-H gels were formed during the hydration, and these gels gradually filled the pores. The SA2NS2 sample is also denser than the control sample, indicating that the incorporation of SA and NS can significantly improve the densification of cement-based materials.

4 Conclusion

The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

The addition of SA was detrimental to the early strength development of cement-based materials, while the combined addition of SA-NS could significantly improve the early strength reduction caused by the addition SA alone.

The early hydration of cement clinker was significantly hindered by the addition of SA, while the incorporation of NS clearly promoted the early hydration; the degree of hydration of the sample containing SA-NS was higher than that of the control sample.

The combined addition of SA and NS can significantly improve the microstructure of hydration products and refine the pore structure, which improves the impermeability and compressive strength of cement-based materials.

Acknowledgement

The financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51908434), the Science and Technology Research Program of the Hubei Province Education Department (Q20191706) and the Nature Science Foundation of the Hubei Province (2020CFB799) are gratefully acknowledged.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.