Effect of mineralogical substitution raw material mixing ratio on mechanical properties of concrete

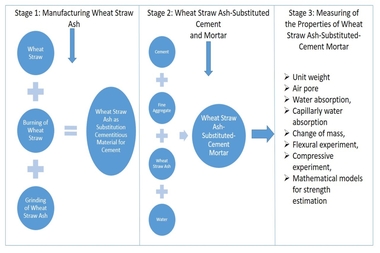

The aim of the original research was to examine and discuss the effects of mineralogical substitution raw material mixing ratios on some mechanical properties of concrete. In this study, fine-particle marble-cutting remnants and fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnants, fine and coarse crushed aggregate, CEM I 42.5N cement and tap water are used as concrete mixing materials. The mineralogical raw substitution material mixing ratio is an independent variable for concrete strength properties. Three substituted concrete groups and one control concrete group were prepared with and without substitution of fine-particle marble-cutting remnants and/or fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnants. The 7-, 14-, 28-, and 90-day compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete were measured with regard to the effects of the mineralogical raw substitution material mixing ratio. The findings unveil that the mineralogical raw substitution material mixing ratio can have positive effects on some mechanical stress factors affecting concrete.

1 Introduction

Turkey has abundant marble reserves and numerous marble-cutting ateliers and factories. Brick is manufactured at about 520 small and medium-sized factories in Turkey. With a total of 57 cement factories, Turkey is a leading producer country in Europe. Indeed, Turkey is one of the top 10 manufacturers in the world [1]. As marble and brick are processed, mineralogical raw material is generated as particulate and scrap material (remnants). According to calculations performed by the author, about 2.592 million t of marble remnant and 3.8 million t of brick remnant accrues in Turkey...

1 Introduction

Turkey has abundant marble reserves and numerous marble-cutting ateliers and factories. Brick is manufactured at about 520 small and medium-sized factories in Turkey. With a total of 57 cement factories, Turkey is a leading producer country in Europe. Indeed, Turkey is one of the top 10 manufacturers in the world [1]. As marble and brick are processed, mineralogical raw material is generated as particulate and scrap material (remnants). According to calculations performed by the author, about 2.592 million t of marble remnant and 3.8 million t of brick remnant accrues in Turkey annually, cf. [2]. In addition to such remnant materials, limestone slag also occurs at quarry facilities. Limestone slag, though, as a normal constituent of quarried material, does not contaminate the environment and is extensively used as aggregate in concrete (Figure 1). Solid waste purification systems are not used for refining marble and brick remnants, so the material is stored on agricultural land, resulting in contamination of the environment (Figure 1). Mineralogical remnants such as fly ash are used in cement manufacturing in India, while South Africa uses brick remnant as aggregate in concrete. In other countries, mineralogical remnant is added to cement and/or concrete.

Some concrete facilities in Turkey use mineralogical remnant as pozzolan. Marble-cutting fine remnant with particle sizes between 150 µm and 2 mm has rich oxide of calcium (CaO) contents. On the other hand, burnt-clay brick remnant that has completed pre-calcination is rich in oxides of silica (SiO2), aluminum (Al2O3), iron (Fe2O3), and calcium (CaO) [2]. Marble and brick remnant should be used neither as filler material on agricultural land nor in concrete due to their aforementioned valuable chemical structure. There have been considerable to excessive amounts of research done on the use of mineralogical additives substituted for sand in mortar beams and for fine aggregate in concrete, including limestone dust filler, ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), rice husk ash (RHA), municipal solid waste ash (MSWA), fly ash (FA), silica fume (SF), etc. [3-24].

For example, Corinaldesi et al. studied the characterization of marble powder (MP) with regard to its chemical and physical properties in order to use it as a mineral additive for sand in mortar and as fine aggregate in concrete. They reported that MP has a very high fineness of 1500 m2/kg, with 90 % of particles finer than 50 μm and 50 % under 7 μm. They also experimentally varied the ratio of water to cementitious material in mortar beams to evaluate the effect of MP on the compressive strength and flexural strength of mortar and concrete. They found that a 10 % substitution of sand with MP provides maximum compressive strength [4]. Lam et al., in [25], focused on compressive strength, splitting tensile strength and elastic modulus, and their results show that combining EAF slag aggregate ratio and 20 % fuel ash improves the mechanical properties in the long term [25]. Viani et al. in [26] found that the water-to-solid ratio influences both compressive strength and setting time positively [26]. A study by Kim [27] explains as an important result that, for a WCP ratio of 15 %, the compressive strength of concrete reaches 30 (MPa) or more on the 28th day [27]. Vurst et al. in [28] investigated the influence of paste volume and water-to-powder volumetric ratio on yield strength, robustness, viscosity, and rheology. Their results establish that, as the water content increases, the yield strength is affected negatively. Conversely, as their last result, increasing the water-to-powder volumetric ratio was seen to improve the robustness of such a mixture [28]. Šipoš et al. in [29] presented the fact that the concrete mixing ratio has an effect of variation on the compressive strength of concrete [29]. Sassani et al. in [30] present important scientific information related to the mixing raw material ratio, such as carbon fiber dosage, fiber length, coarse-to-fine aggregate volume ratio (C/F), conductivity-enhancing agent (CEA) dosage, and fiber dispersive agent (FDA) dosage. Their results show that dosing fiber, CEA, and FDA influence compressive strength positively. Moreover, the C/F ratio and the FDA dosage are important variables with which to enhance flexural strength [30].

On the other hand, there has been comparatively little research done on the partial substitution of fine-particle marble-cutting remnant and fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnant for fine aggregate and cement in concrete. In 2011, Ergün carried out some experiments on concrete prepared with partial substitution of diatomite soil powder and marble powder for cement. Experimental results presented by researchers report that concretes containing 5 % marble powder, 10 % diatomite soil powder, and both 5 % marble powder and 10 % diatomite soil powder show the best compressive strength and flexural strength. However, the substitution of diatomite soil powder for cement, of marble powder for cement, and of both marble powder and diatomite soil powder for cement with addition of superplasticizer shows that marble powder and diatomite soil powder can be added to enhance mechanical properties of conventional concrete such as compressive strength and flexural strength [31]. In 1987, Yuan discussed in [32] the mechanism of formation of a structure within the MP-Portland cement interfacial zone and its relationship to bond strength. Formation of an MP-Portland cement interfacial zone appears to take place by way of subsequent non-homogeneous nucleation of portlandite (CaOH2) and calcium-silica-hydrate (C-S-H) gel. The paper presents the fact that the formation of carboaluminate (CA) has a beneficial effect at the cement paste interface in terms of bond strength, while excessive carbonate dissolution and the reduction of portlandite are negatively influenced at the interface by the existing bond between marble particles and cement paste [32].

In 2010, Wild et al. did research on brick powder (BP) from Europe. BPs from Britain, Denmark, Lithuania and Poland were ground up and examined with regard to their effect on mortar strength, particle size distribution, chemical composition, and mineral content. The chemical composition of the BP confirmed that all types of BP examined in that research had good pozzolanic activity. This finding is supported by the strength development of mortar beams prepared by BP-blended cement. Moreover, the authors report that BP has potential for utilization in the production of durable mortar and concrete [33].

1.1 Purpose of the study

The current paper summarizes the results of an experimental procedure that scrutinized some strength properties of concrete containing fine-particle marble-cutting remnants and fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnants for use in fine aggregate and/or cement. The effect of fine-particle marble and of fine-particle brick on the compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete is considered with regard to the resultant change in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio. It does not address either the fresh properties of concrete or the substantial environmental impact of using marble waste and brick waste in concrete. The partial substitution of fine-particle marble and fine-particle brick for cement or fine aggregate reduces the volume of marble waste and brick waste, but the main concern is how the fine-particle marble and the fine-particle brick influence the compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete.

Thus, the original research presents experimental results regarding the effect of changes in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio on the compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Fine-particle marble-cutting remnant (FMP) and fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnant (FBP) were added to concrete mixes composed of fine crushed aggregate (FCA), coarse crushed aggregate (CCA), cement (as CEM I 42.5 N), and water as mineralogical substitution raw material.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Preparation of concrete

The target fresh and hardened properties of concrete were:

the C25-C35 concrete compressive strength category

a 60 % water-to-cement ratio for concretes in Group1, Group2, and Group4 (Control)

a 70 % water-to-cement ratio for concretes in Group3

a maximum of 65 mm slump in concretes

a maximum of 5 % air content in concretes

a 32-mm maximum grain size of the crushed aggregate

between 270 – 337 kg/m3 cement dosage of the concrete groups [34]

A total of 240 concretes were prepared according to the target properties. Of those 240 concretes, 120 were compacted in 150 x 300 mm cylindrical molds with an immersion vibrator for the compressive strength experiment, and the other 120 concretes were compacted in 100 x 100 x 500 mm prism molds on a table vibrator for the flexural strength experiment. Four groups of concrete were cured in water for 7, 14, 28 and 90 days. Prior to the compressive strength experiment, the 120 cylindrical concretes were headed with sulfur. Groups, types and mixture proportions of concrete are given in Table 1.

2.2.2 Measuring the compressive strength and computing the change in compressive strength

The TS EN 12390–3 standard method explains how to measure the compressive strength of concrete prepared with the 120 cylindrical, sulfur-headed samples at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. The compressive strength of concrete was computed using the standard equation of a compressive-strength/compression-force divided field assuming an applied compression force [35]. Equation (1) was used to compute the change in the compressive strength of the concrete made with fine-particle marble-cutting remnants and with fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnants.

⇥(1)

fcsa: change in compressive strength of concrete [%]

Mcs: compressive strength of Group1, Group2, and Group3 concrete [MPa]

Rcs: compressive strength of control concrete [MPa] and/or target compressive strength indicated in 2.2.1 Preparation of concrete

2.2.3 Measuring the flexural strength and computing the change in flexure moment

The TS EN 12390–5 standard method explains how to measure the 7-, 14-, 28- and 90-day flexural strength of concrete prepared with 120 prism samples. The flexural strength of the concrete was computed using the standard equation of flexural strength quoted in the above standard [36]. Equation (2) was used to compute the change in the flexural strength of the concrete made with fine-particle marble-cutting remnants and with fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnants.

⇥(2)

ffsa: change in flexural strength of concrete [%]

Mfs: flexural strength of Group1, Group2, and Group3 concrete [MPa]

Rfs: flexural strength of control concrete [MPa]

2.2.4 Statistical assessment

Excel was used to construct tables and figures depicting the changes in compressive strength and flexural strength of the concrete. The origin line of the X-axis in Figures 2 to 9 shows a strength limit of the control concrete. The effect of marble and brick fine particle is positive if the change is marked above the X-axis in Group1, Group2, and Group3. The effect of marble and brick fine particle is also negative, if the change is marked under the X-axis. The Y-axis represents the percentage change in compressive strength and flexural strength.

3 Data and arguments

Table 2 presents the mineralogical substitution raw materials mixing ratio, concrete groups, and types. Table 3 gives the change in compressive strength and flexural strength in Group1, Group2, and Group3 concrete, and the 7-day, 14-day, 28-day and 90-day compressive strength and flexural strength of the control concrete, plus the target compressive strength (in bold) and the percentage change in compressive strength with regard to target C25 concrete (in bold).

3.1 Compressive strength of concrete

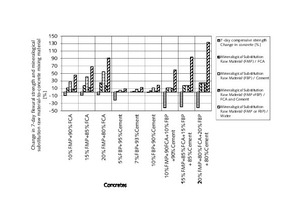

Figure 2 compares the changes in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 7-day compressive strength of concrete compared to that of the control concrete, in Group1, Group2, and Group3.

It was observed that an increase in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio underlies positive growth in the compressive strength of the concrete (except for Group3). As mineralogical substitution raw material such as fine-particle marble and fine-particle brick is substituted for both fine aggregate and standard cement in Group3, the compressive strength of the Group3 concrete decreases at the 7-day point (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 2). The surplus of mineralogical substitution raw material (FMP and/or FBP)-to-water ratio, 59.3 % to 133.6 %, may be a major reason for the decrease in compressive strength, although the water-to-cement ratio was 0.70 in Group3 concrete. Another reason may also be that the fine-particle burnt-clay brick remnant needs much more water than the fine-particle marble-cutting remnant. The purpose of the concrete mixing water is to wet the surface of the aggregate and provide for the hydration of cement. In addition, the mixing water in Group3 concrete served to combine the cement particles, the FMP and the FBP in the hydration process, which is an exothermic chemical reaction promoting the setting of concrete. When the FBP absorbs too much water from concrete mixing, the hydration process slows down to influence the compressive strength negatively in Group3 concrete.

The average 7-day compressive strength of 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete, 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete and 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete was more than 4 % higher than that of the control concrete, Group4. The greatest change in the 7-day compressive strength of the concrete was observed in the 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete sample, with more than 9 % growth. This implies that the gain in 7-day compressive strength is based on the calcium oxide forming the mineralogical structure of fine-particle marble, which is latent hydraulic substitution in Group1. Since the ratio of fine-particle marble takes the place of 10 % to 20 % of the fine aggregate, the concrete in Group1 shows rapid initial setting and pre-compressive strength development at 7 days. The average 7-day compressive strength of 5%FBP+95%cement concrete and 10%FBP+90%cement concrete was more than 3 % lower than that of the control concrete, in Group2, except for the 7%FBP+93%cement concrete. The compressive strength of 7%FBP+93%cement concrete was more than 0.7 % higher than that of the control concrete at 7 days. This implies that the gain in 7-day compressive strength of 7%FBP+93%cement concrete and 10%FBP+90%cement concrete is attributable to the calcium oxide, silica oxide, aluminum oxide and iron oxide based mineralogical structure of fine-particle brick, which has an artificial pozzolanic effect on cement hydration. On average, the 7-day compressive strength of Group2 concrete was more than 19 % lower than that of the control concrete (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 2). Figure 3 compares the change in mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and the change in 14-day compressive strength of Group1, Group2, and Group3 concrete compared to the control concrete.

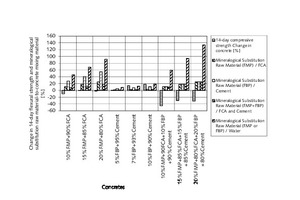

As the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio increases, the compressive strength of the 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete, 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete, 10%FBP + 90% cement concrete, 15 %FMP +85% FCA +15 % FBP +85 % cement concrete, and 20%FMP +80% FCA +20% FBP +80 % cement concrete decreases at 14 days. In contrast to the last findings related to the decrease in the compressive strength of the 14-day concrete, the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio caused an increase in the compressive strength of 15 % FMP +85 % FCA concrete, 5 % FBP +95% cement concrete, 7% FBP +93% cement concrete and 10% FBP +90% cement concrete at the 14-day strength development point. The average 14-day compressive strength of 10%FMP+90%FCA and 20% FMP +80% FCA concrete was more than 2 % lower than that of the control concrete, while the average 14-day compressive strength of 15% FMP +85% FCA concrete was more than 1% higher than that of the control concrete; the average 14-day compressive strength of Group2 concrete was more than 4 % higher than that of the control concrete; and the average 14-day compressive strength of Group3 concrete was more than 22 % lower in comparison with the control concrete. The greatest change in 14-day compressive strength was in that of the 10%FBP+90%cement concrete, with more than 8 % growth (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 3). Raising the FMP-to-FCA ratio between 142.3 % and 225 % had positive effects on compressive strength. Thus, FMP could be defined as an initial and final compressive strength activator. Figure 4 compares the change in mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and the change in 28-day compressive strength of concrete as control concrete, plus the 28-day compressive strength change in concrete as target C25 concrete in Group1, Group2 and Group3.

When the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio was increased, the 28-day compressive strength of Group1 and Group2 concrete also increased, but not that of the 10%FMP+90%FCA and of the Group3 concrete. The average 28-day compressive strength of the 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete was more than 2 % lower than that of the control concrete; the average 28-day compressive strength of 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete and 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete was more than 7 % higher than that of the control concrete; the average compressive strength of Group2 concrete on the 28th day was more than 14 % higher as compared to the control concrete; and the average 28-day compressive strength of Group3 concrete was more than 13 % lower than that of the control concrete (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 4). Group1, Group2, Group3 and the control concrete have higher compressive strength, between 20 % and 70 %, as compared to the target concrete’s compressive strength, i.e., that of C25 concrete (25 MPa). Figure 5 compares the change in mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 90-day compressive strength of concrete compared to that of the control concrete, in Group1, Group2, and Group3.

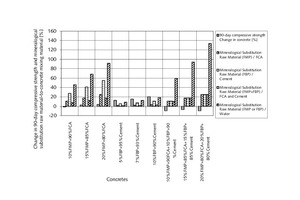

The average 90-day compressive strength of the 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete and Group3 concrete declined with each increase in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, up to 225 %. The average 90-day compressive strength of 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete, 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete, and Group2 concrete increased with each rise in the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio. The average 90-day compressive strength of 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete was more than 1% lower than that of the control concrete, and the average 90-day compressive strength of 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete and of 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete was more than 3 % higher as compared to the control concrete. The average 90-day compressive strength of Group2 concrete was more than 16 % higher than that of the control concrete, and the average 90-day compressive strength of Group3 concrete was more than 8 % lower than that of the control concrete (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 5).

3.2 Flexural strength of concrete

Figure 6 compares the change in mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 7-day flexural strength of concrete. The 7-day flexural strength diminishes as the mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio (FMP/FCA) increases. The average 7-day flexural strength of Group1 concrete was more than 8 % lower than that of the control concrete. The average 7-day flexural strength of 5%FBP+95%cement concrete and 10%FBP+90%cement concrete was more than 11 % lower as compared to the control concrete, when the mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio (FBP/Cement) increased by up to 211 %. For that reason, the FBP/cement ratio has a positive impact on the flexural strength of concrete, even if the concrete contains less cement than does the control concrete.

The average 7-day flexural strength of the 7%FBP+93%cement concrete was more than 0.3% higher than that of the control concrete. The average 7-day flexural strength of Group3 concrete was more than 40 % lower than that of the control concrete (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 6). Figure 7 compares the change in mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 14-day flexural strength of concrete compared to the control concrete.

The change in the 14-day flexural strength of Group1 and Group3 concrete was impaired by the increase in mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio. On the other hand, the 14-day flexural strength of Group2 concrete increased. The average 14-day flexural strength of Group1 concrete was more than 4 % lower than that of the control concrete. The average 14-day flexural strength of Group2 concrete was more than 10 % higher as compared to that of the control concrete. Thus, the author noticed that the effect of the FBP/cement ratio on flexural strength remained positive. The average 14-day flexural strength of Group3 concrete was more than 35 % lower than that of the control concrete (Table 2 and Table 3, Figure 7). Figure 8 compares the change in mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 28-day flexural strength of concrete compared to the control concrete.

The 28-day flexural strength of Group1 and Group3 concrete weakened as the mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio was augmented. The 28-day flexural strength of Group2 concrete increased along with any increase in the mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio. The average 28-day flexural strength of Group1 concrete was more than 3 % lower than that of the control concrete. The average 28-day flexural strength of Group2 concrete was more than 12 % higher than that of the control concrete. Thus, the FBP, which contained, in all, 68.76 % SiO2+Al2O3+Fe2O3, had a positive activator effect on the flexural strength of concrete at 28 days. The average 28-day flexural strength of Group3 concrete was more than 27 % lower than that of the control concrete. 10%FBP+90%cement concrete had the greatest 28th-day flexural strength (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 8). Figure 9 compares the change in mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio, concrete types, and 90-day flexural strength of concrete with those of the control concrete.

The average 90-day flexural strength of 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete, 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete and Group3 concrete decreased, when the mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio was raised. The average 90-day flexural strength of 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete and Group3 concrete increased along with an increasing mineralogical substitution material-to-concrete mixing material ratio. While the average of 90-day flexural strength of the 10%FMP+90%FCA concrete and the 15%FMP+85%FCA concrete was more than 2 % lower than that of the control concrete, the 90-day flexural strength of the 20%FMP+80%FCA concrete was more than 5 % higher than that of the control concrete. The average 90–day flexural strength of Group2 concrete was more than 14 % higher than that of the control concrete. The average 90-day flexural strength of Group3 concrete was more than 27 % lower as compared to that of the control concrete. As expected, like the 28-day flexural strength, the 10%FBP+90%cement concrete exhibits the highest 90-day flexural strength (Table 2

and Table 3, Figure 9). Since the FBP/cement ratio had a positive effect on flexural strength between the 7th and the 90th day, the FBP could be described as a flexural strength activator for concrete, even if it replaces up to 10 % cement.

4 Conclusions

The most significant conclusion inferred from these research results regarding interaction between the compressive strength, the flexural strength and the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing material ratio is explained below:

In view of the positive effect of the mineralogical substitution raw material-to-concrete mixing ratio on compressive strength and flexural strength, the fine-particle marble (FMP) substituted for fine crushed aggregate in concrete mixing could be defined as an initial and final compressive strength activator. The fine-particle brick substituted for cement in concrete mixing could be described as both a compressive-strength and a flexural-strength activator. Moreover, the fine-particle marble substituted for fine crushed aggregate and the fine-particle brick substituted simultaneously for cement in concrete mixing provide controlled, steady gains in the compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete

As the fine-particle marble and fine-particle brick had no negative effects on the subject strength properties of concrete, the employed concrete mixing design could be commercialized for the construction industry, i.e., for fields such as roller compacted concrete, self-consolidating concrete, heavy weight concrete, pavement concrete and so on. Thus, both the compressive strength and the flexural strength of the concrete rose steadily on incorporation of 10 % fine-particle brick in substitution for cement as the final strength increment at 90 days. The mixing design of 10%FBP+90%cement concrete stands as the best prescription.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.