Advances in physical and mechanical properties of wheat straw ash-substituted cement mortar

Water exists naturally in three forms: above-ground water resources such as rivers, lakes and seas, underground water resources and water vapour in the atmosphere. Ceramic-structured construction materials such as concrete, stone and brick are intrinsically porous materials. Structural systems that are manufactured using such construction materials are generally located in one of these environments and affected by the environment. If a construction is located within water, the affecting factors are the porous system of the construction element and water pressure. If the construction or element is in superficial contact with water, the water passes with capillary pressure effect through capillary channels within the material structure. Porous systems that exist in construction materials are reduced or the structural systems are made impervious to water by using waterproofing materials. Within essential construction materials, some additives to cement are used in concrete production in order to reduce the amount of porosity, improve qualities, increase durability and ensure the affordability of concrete in a particular way. This study outlines the effect of wheat straw ash, which is one of the pozzolanic materials investigated with the aim of reducing the amount of porosity and size of concrete, preventing continuity of capillary pores, minimizing their permeability and improving concrete strength qualities.

1 Introduction

Globally, wheat seed is the main product derived from the wheat plant. According to the Supply and Demand Report of U.S. Wheat Associates, which was published on June 11th, 2020, 773 million t of wheat will be produced this year, while about 753 million t of wheat will be consumed worldwide in food, in feedstock, and also in non-food applications, primarily in binder manufacture [1]. The wheat plant is not only a source of wheat seed but also of wheat straw, a lignin and holocellulose carbohydrate based biopolymer fibre [2, 3]. Wheat straw is an abundant, cheap, and biodegradable...

1 Introduction

Globally, wheat seed is the main product derived from the wheat plant. According to the Supply and Demand Report of U.S. Wheat Associates, which was published on June 11th, 2020, 773 million t of wheat will be produced this year, while about 753 million t of wheat will be consumed worldwide in food, in feedstock, and also in non-food applications, primarily in binder manufacture [1]. The wheat plant is not only a source of wheat seed but also of wheat straw, a lignin and holocellulose carbohydrate based biopolymer fibre [2, 3]. Wheat straw is an abundant, cheap, and biodegradable product that is obtained from renewable resources. Researchers take these advantages into account. Since wheat straw is accepted as an attractive material, there are a variety of applications in the energy generation sector [4, 5], in the production of cattle fodder [6], and in in the construction materials industry as an admixture in the form of wheat straw ash (WSA) for durability modification, water absorption and capillary water absorption reducer, and as a strength increaser in cement-based materials (CBMs) [2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10]. In the last two decades, wheat straw ash, which contains over 83.8% of crystalline silica, has been evaluated in cement and CBMs as synthetic pozzolan, for use either as a supplement for cement-based material or as a substitute material for cement [2, 3]. For instance, in 2002 Al-Akhras and Abu-Alfoul published a very important article relating to the effect of wheat straw ash on the mechanical properties of autoclaved mortar. They replaced mortar sand with three percentages of the WSA: 3.6%, 7.3%, and 10.9%. Their autoclaved mortar made of limestone sand and 10.9% WSA increased in flexural strength, compressive strength, and splitting tensile strength by 71%, 87%, and 67%, respectively, when compared to mortar without the WSA [11]. Martirena and Monzó were among the scientists who worked on WSA in 2018. They presented the benefits of using vegetables ashes as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Their work revealed that the agricultural ashes demonstrated good reactivity within cement-based materials if the agricultural renewable resources were burned at temperatures between 600 °C and 700 °C [8]. One of the last significant studies comparing the retarding mechanisms of ZnO and sucrose in cement hydration and interactions with such SCMs as wheat straw ash, rice straw ash, silica fume, metakaolin, and fly ash was conducted by Ataie et al. in 2015. The experimental results of this work indicated that the mechanism of the ZnO-retarded hydration reaction could be nucleation and/or growth impedence of the C-S-H gel. This study also provided a better understanding of the interaction between SCMs and cement hydration retarders essential in estimating the dosage effect of the retarder [9]. The last significant study on recent advances in understanding the role of SCMs in concrete was carried out by Juenger and Siddique in 2015. They reviewed the advances in information provided by research in the field, emphasizing the effect of the research on the sector. They also found that this practice was favourable to the industry, currently resulting in concrete with lower cost, lower environmental impact, higher long-term strength, and improved long-term durability [10].

On the other hand, cement-based mortar, which can be easily shaped in structure manufacturing and enables continuous construction material production, is widely used in the world, and its sustainability has to be provided by way of an environmentally friendly solution. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the WSA research is particularly aimed at increasing the sustainability of CBM. However, structures containing the CBMs constitute a significant portion of present day structural systems. Different parts of a structure can be situated in the atmosphere, on the ground or within water and affected by water repelling force. The porous structure of the CBM gains importance in water structures, such as dam bodies, water reservoirs, water channels and flumes, due to water absorption by capillarity [12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

In other words, permeability is also of considerable importance in other structures in terms of the porous structure of the CBM, saturation with water resulting in such damage as expansion and shrinkage by freeze and thaw effect, the corrosive effect of deleterious water, increases in pore size, and weakening of the Ca(OH)2 compound, which dissolves in the CBM over time. There are visible and non-visible, continuous and non-continuous pores of all sizes in the inner structure of CBMs. Particularly, large and continuous pores lead to the passage of liquid and gas through material, and absorption of gas and liquid by its outer surface. It is hard to make a thorough classification due to porous structures within materials being irregular and very complex, but it is currently possible to sort pores into two groups as continuous (open) and non-continuous (closed) pores. Pores within CBMs can be classified as follows: a) Pores in own structure of aggregate grain. Usually, aggregate pores are of small diameter and vary according to the type, diameter and form of aggregate; b) Pores within hardened cement paste are gel, capillary and large pores. Pores between 10 (Aº) and 35 (Aº) in size are defined as gel pores while pores between 60 (Aº) and 106 (Aº) in size are defined as capillary pores within hardened cement paste. The amount, diameter and shapes of these pores vary depending on the water-to-binder ratio of the CBM, the hydration level, the greatest grain size of the aggregate stack, binder type etc. Permeability and the freeze-thaw phenomenon cause a huge expansion within this pore system in the CBM. Capillary pores, which are usually connected to each other, may lose their continuity when the development of hydration phenomenon results in clogging; c) Large pores are greater than 0.1 mm in size within cement paste. They are pores that remain within the aggregate bulk. These pores particularly stem from failing to place concrete well and are seen in dry-consistent concretes. They emerge in cases where fine material does not fill pores in between the aggregate grains; d) Pores caused by different settling of concrete are pores that remain under coarse aggregate grains due to prevention of concrete settling in any way and especially as a result of coarse aggregate grains failing to follow this settling; e) Nodular air pores that form when concrete of plastic consistency fills in between aggregate grains of the cement paste. Also, there are cracks and pores in the concrete caused by expansion and shrinkage. As hydration progresses, the absolute volume of cement and water progressively declines. Cement paste with any water-to-cement ratio at the end of hydration does not completely fill the volume that the fresh cement paste does at the beginning, so that shrinkage cracks form [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. The continuity and extent of the porous systems described above are important with respect to the concrete’s permeability, water absorption, capillary water absorption, unit weight, flexural strength, compressive strength and durability.

As water and air pores inside CBM connect with each other, they will act as a concrete-like permeable material. The permeability of cement paste, which serves as a binder for the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) in the aggregate stack in concrete, is a decisive factor in concrete durability. The permeability coefficient of cement paste is not only a function of porosity but also of the surface area of hydrated products and free energy for flow [17]. Other than this, cement pastes with a large specific surface may thereby retain large amounts of water in case of balance, further slowing the passage of moisture [18]. When the mechanism related to strength is looked at in Portland cement pastes manufactured from pozzolans by adding fly ash, attributes such as water-proofing and high chemical resistance are seen in fly ash-added cement paste. Assuming that fly ash particles provide fast and easy nucleation of cement hydration products in paste, these products may clog and cover fly ash cenospheres one by one. After the first cycle, the former increases and the latter decreases as a result of the change in porosity and strength, and of the pozzolanic reactions [19].

Solutions that contain salts of non-organic acids, such as pure waters, sulphate, chloride, and nitrate and organic acid solutions such as acetic acid and lactic acid can be counted among the most hazardous waters in terms of impact on the aforementioned structural systems. Corrosion occurs as a time function in concrete structures that are affected by these waters. When concrete is subjected to corrosive environment effects, new compounds form as a result of reactions among solutions in the environment and the cement hydration products Ca(OH)2 and 3CaO∙Al2O3. These reaction products cause volume expansion, softening and dissolution of the concrete structure. As a result, negative changes in the concrete attributes occur depending on the type, concentration, heat and impact time of the solution. Precautions to be taken to minimize such corrosive problems can be summarized as manufacturing concrete using special type cements, using special additives or both. And pozzolanic cements provide the solution to this kind of concrete-related problem. The fact that pozzolan is more durable in an aggressive environment is attributed to the lower Ca(OH)2 content, the low permeability of the product, different composition of the cement gel and the instability of the ettringite that forms in pozzolanic cement [20].

In the light of the knowledge outlined above, this study aims at evaluating flow, unit weight, water absorption, capillary water absorption, change of mass, flexural strength, and compressive strength, which are known to be significant attributes of CBMs and of mortar containing wheat straw ash. It also seeks forceful correlations between physical features and mechanical features of the mortar in order to set up mathematical regression equations.

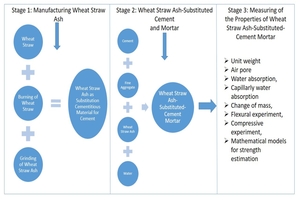

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials used

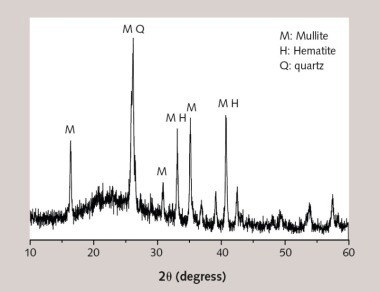

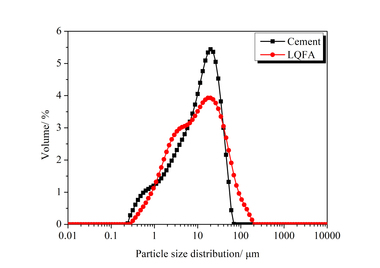

In this study, samples were produced according to TS EN 197-1. The materials used were standard RILEM sand, Portland cement (CEM I 42.5 N) and wheat straw ash with the attributes provided in Tables 1 and 2 as pozzolanic material, as well as commercially obtained plasticizer additive. Types of sample according to the amounts of materials used in production and ash ratio are shown in Table 3.

Flow and unit weight experiments of fresh mortar, water absorption in volume, capillary water absorption, change in unit mass, flexural and compressive experiments of hardened mortar were performed on days 0, 28, 56, 90, and 208 as is done in the production in mortars, and the results are provided in the following figures as a time-dependent change of relative values. The non-ash-added reference mortar’s value on day 28 was based on determined relative values. Mass change in the samples was determined by taking the day when mortar was removed from the form as the beginning, while the time-dependent change of relative value is provided in the following tables by proportioning it to the initial values.

2.2 Experimental study

An experimental study, which was conducted with the aim of evaluating mortar permeability, the impact of synthetic pozzolanic material on flow, unit weight, water absorption, capillary water absorption, change in mass, flexural strength, and compressive strength, and the correlation between those properties was drawn upon in this present study. In experiments, the agricultural residue wheat straw ash was used as synthetic pozzolanic material [21].

Ash-added and non-ash-added mortars were produced. The effect of wheat straw ash on flow, unit weight, water absorption, capillary water absorption, change in mass, flexural strength, and compressive strength was examined. The mass amount of ash added to the cement was 8%, 16% and 24%. Due to the large specific surface of ash, an increased amount of mixing water was needed for the mortar. In order to ensure equal workability with PCA fresh mortar, plasticizer was used as admixture in PCB, PCC and PCD fresh mortars. The flow and unit weight experiments were performed within 4 min as soon as the cement and sand and water were mixed with each other. After the preliminary fresh mortar experiments, prismatic specimens 40x40x160 mm were moulded for use in the flexural and compressive strength tests. Ash-added and non-ash added mortars were preserved within water at 20±2 °C for 27 days by removing from the mould 24 h after production. Flexural and compressive experiments of water absorption in volume and capillary water absorption were carried out on days 28, 56, 90, and 208 in the experiment schedule.

2.2.1 Physical experiments

To better explain, the physical experiments were carried out in two different stages: the physical experiments for fresh state of mortar and the physical experiments for hardened state of mortar. In the first stage, the flow and the unit weight experiments were measured from the fresh state of mortar with and without wheat straw ash. In the second stage, the unit mass, the water absorption in volume, the capillary water absorption, and the mass change experiments were performed to determine the change in physical properties of hardened mortar with and without wheat straw ash.

2.2.1.1 Air pore experiment

Air content experiments were performed on fresh mortar samples according to the rules in BS EN 413-2 and ASTM C185-20. The following steps explain how the air pore is measured; (1) fill a sample of mortar into one litre capacity cylinder of an air meter in three layers, (2) compact each layer by tamper and/or by vibrator, (3) clamp the cover of the cylinder, (4) fill water into the assembly to let air escape through valve, (5) close the valve and increase the internal pressure with a pump, (6) watch the fall in water level in the graduated cylinder, (7) before the pressure exceeds 2.5 (bar), record the water level reading, (8) then release the pressure to let the water level rise, (9) record the difference between the two water levels as apparent air pore [22, 23]. The unit weight in fresh mortar was found by utilizing the correlation (1) below

A = x 100⇥ (1)

Where A is the air pore of fresh mortar, in (%); Va is the volume of air pore, in (dm3); and V is the cylinder volume of the air meter in (dm3).

2.2.1.2 Unit weight experiment

Unit weight experiments were performed on fresh mortars before they were moulded for hardened mortar experiments. The unit weight in fresh mortar was found by utilizing the correlation (2) below.

γUW = ⇥(2)

Where γUW is the unit weight in g/cm3; md is the mass of fresh specimen in grams; and V is the volume of fresh specimen in cm3 [24].

2.2.1.3 Water absorption in volume experiment

Values of water absorption in volume were found by utilizing the correlation (3) below and values of measurement carried out in all groups in samples with dimensions 40x40x50 mm on days 28, 56, 90 and 208, and the graph for the time-dependent change of relative values is shown in Figure 3.

%hs = x 100⇥ (3)

Here, hs indicates the ratio for water absorption (%) in volume, Wk indicates dry weight (g) of the sample, Wsh indicates weight (g) in air of the water-saturated sample, Wss indicates weight (g) in water of the water-saturated sample.

2.2.1.4 Capillary water absorption experiment

The capillary water absorption experiment was performed on days 28, 56, 90 and 208 on samples with dimensions 40x40x50 mm. The experiment determined the dry weight Wk of the samples, which were first dried in an oven at 105±5 °C to constant weight and cooled in a desiccator to room temperature. In the experiment, the 40x40 mm surface of the samples, which was in contact with water, was measured with the 1/20 vernier division calliper and the average actual values of the surfaces were calculated. Samples were placed on glass rods within an enamelled bathtub levelled with water gauge and the contact of samples with water was ensured. The water amounts (Q) absorbed from the surface by capillarity were determined by gauging in the 1st, 4th, 9th, 16th, 25th, 36th, 49th and 64th minutes after the beginning. Linear regression analysis was conducted between Q/F and Vt to determine capillarity coefficient. The graph for time-dependent change of relative values, which were found by proportioning the determined capillary water absorption coefficient (K) to the reference mortar’s value on day 28, is shown in Figure 4. From the correlation (4), K was calculated as capillarity coefficient (cm2/s).

K = ⇥ (4)

In the correlation, K indicates capillarity coefficient (cm2/s), Q indicates the water amount (cm3) absorbed by the sample, F indicates the capillary water-absorbed sample surface (cm2), t indicates the sample’s water absorption time (s) via capillarity.

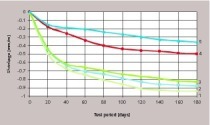

2.2.1.5 Change of mass experiment

Change of mass experiments were carried out on 3 prism samples with dimensions 40x40x50 mm. Samples, which were taken out of water on day 28, were weighed in a 0.1 g precision scale by slightly drying their outer surfaces. Samples cured in water were weighed in the same way until day 180 by taking them out of the environment in which they were present on every 14th day of the periods. Values calculated from the correlation (5) below were proportioned to the average value of mass of the reference mortar on day 28. The determined time-dependent change of relative value is shown in Figure 5.

W = x 100⇥(5)

In the correlation, W is the mass change ratio (%), WSH is the sample mass (g) at (t) time and Wk is the initial sample mass (g).

2.2.2 Mechanical experiments

Mechanical and physical experiments were conducted representing the reference group in both groups of samples, which were removed from the water on day 28. Other samples were preserved in lime-saturated water at 20±2 °C until days 28, 56, 90 and 208 when compression, water absorption in volume and capillary water absorption experiments were performed. Flexural and compressive experiments were conducted on days 28, 56, 90 and 208 to evaluate the impacts on mortars of wheat straw ash, which was determined to possess pozzolanic properties through physical, chemical and mechanical experiments. Water absorption in volume and capillary water absorption experiments were conducted on the same days and their masses were measured.

2.2.2.1 Flexural experiment

Flexural experiments in samples were carried out in Michaelies flexural instrument in 3 prism samples with dimensions 40x40x160 mm, which were produced in compliance with international standard, according to cure age on days 28, 56, 90, and 208. The force that causes fracture in flexural effect was determined by loading prism samples from their middle cross sections. Flexural strength was calculated drawing on the correlation (6) below. The time-dependent change of relative value, which was found by proportioning to the average flexural strength of the reference mortar on day 28, is provided in Figure 1.

ƒce = 1.5 x ⇥ (6)

In the correlation, fce indicates flexural strength (N/mm2), Pk indicates fracture force (N), L indicates the distance between bearings and b indicates the sample cross-section dimension (mm).

2.2.2.2 Compressive experiment

The cube compressive experiment was conducted on 6 samples by utilizing 40x40 mm steel caps on the fractured parts from the flexural experiment according to international standard. In the experiment, the fracture force Pk was determined by using a Universal Press with a capacity of 350 kN. The compressive strength was calculated from the correlation (7). Relative values were found by proportioning these values to the compressive strength of the reference mortar on day 28 and are shown in Figure 2.

ƒcb =⇥(7)

In the correlation, fcb indicates compressive strength (N/mm2), Pk indicates fracture force (N) and b indicates the sample cross-section dimension (mm).

3 Experimental results and discussions and

mathematical modelling

3.1 Physical properties

Table 4 gives averages and standard deviations of air pore and unit weight wheat-straw-ash-added and non-wheat-straw-ash-added mortar in fresh state, as well as water-to-binder ratio, water-to-sand ratio, plasticizer-to-water ratio, ash-to-cement ratio, cement-to-sand ratio, and ash-to-sand ratio. Table 5 presents types of physical experiment, types of mortar, averages and standard deviations of relative water absorption in volume and of relative capillary water absorption and of relative change of mass, and days of physical experiment.

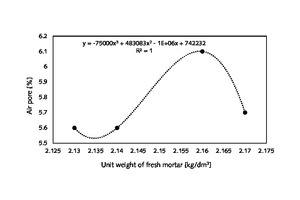

3.1.1 Air pore of fresh mortar

Table 4 presents averages and standard deviations of air pore of wheat-straw-ash-added and non-wheat-straw-ash-added mortar in fresh state, as well as water-to-binder ratio, water-to-sand ratio, plasticizer-to-water ratio, ash-to-cement ratio related to air pore property in the CBM. Figure 1 also shows an important relationship between air pore and unit weight of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement, a mathematical equation, and relationship degree as R2 which equals 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties.

As the substitution ratio of wheat straw ash for cement was increased from 0% to 24% in mortar, the air pore properties did not remain constant. The average air pore of wheat-straw-ash-addedwheat-straw-ash-added mortar diverges from the average air content of non-wheat-straw-ash-addedwheat-straw-ash-added mortar. Wheat straw ash substitution for cement led to a reduction in air pore content of between 7% and 8.1% (Table 4). Research on air pore content of mortar reveals that the use of WSA causes a loss of air pore content. The result from this study states a similar conclusion for the air pore content of wheat-straw-ash-addedwheat-straw-ash-added mortar. It is possible to clearly understand from the results of wheat-straw-ash-added mortar that as the WSA increases up to 24% in mortar, the air pore content decreases tangibly. In Figure 1, a polynomial equation is adopted to show the relationship between air pore and unit weight of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement. The relationship degree of R2 is also provided in Figure 1 and shows a good compatibility between two specified properties. As the relationship degree of R2 is very close to 1, the air pore content could be estimated by testing at least one of the unit weights of fresh mortar specimens with the equation in Figure 1.

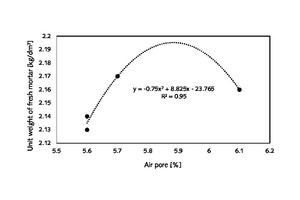

3.1.2 Unit weight of fresh mortar

Table 4 presents the averages and standard deviations of unit weight of wheat-straw-ash-added and non-wheat-straw-ash-added mortar in fresh state, as well as cement-to-sand ratio and ash-to-sand ratio related to the unit weight property in the CBM. Figure 2 also shows an important relationship between unit weight and air pore of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement, a mathematical equation, and relationship degree as R2 which is very close to 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties.

In mortars, the interlocking of the fine aggregate and cement paste forms an interfacial transition zone (ITZ), which is described as a weak phase, because of the effect of various sizes of fine aggregate and cement and supplementary cementitious material [25, 26, 27]. The incompatibility of particles between the fine aggregate and cement and wheat straw ash negatively affects the unit weight of mortar. These results verified the aforementioned knowledge. The lowest unit weight is in the PCD, since it contains 24% WSA. The PCC and PCD are respectively lower over 0.92% and 0.98% than that of the PCA. There is only 0.46% growth in unit weight of PCB when compared to PCA. These results show that the unit weight percentages are reduced by raising the WSA content from 8% to 24% in the wheat-straw-ash-added mortar system [28]. In Figure 2, a polynomial equation is adopted to show the relationship between unit weight and air pore of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement. The relationship degree of R2 is also provided in Figure 2 and shows a good compatibility between two specified properties. As the relationship degree of R2 is very close to 1, the unit weight content could be estimated by testing at least one of the air pores of fresh mortar specimens with the equation in Figure 2.

3.1.3 Water absorption in volume

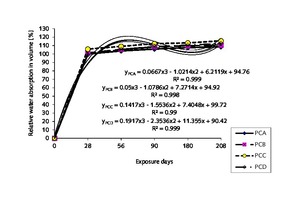

Pozzolans are materials that contain a great deal of active SiO2 and a small amount of oxides such as A12O3, Fe2O3, CaO and MgO. When vitrified active silica in pozzolanic material is mixed with lime, it gains a binding attribute in a wet environment and transforms into calcium silicate salt that is insoluble in water. It constitutes insoluble silicate salt by also combining with Ca(OH)2, which is the hydration product of cement and dissolves in water. Due to this characteristic of mortar hydration products, pozzolans positively influence the water durability of cement mortar [29]. Adding pozzolan instead of a portion of cement increases plasticity, prevents water bleeding and thaw phenomena, as well as decreasing the hydration heat and permeability of mortar [30]. Pozzolans are separated into two classes as natural and synthetic according to their mode of formation [15, 30, 31]. Materials that are known as natural pozzolan are volcanic ashes, clay schist, diatomite soil, pumice stone, etc. They are found in certain regions in the world. The chemical structure and activity of pozzolans vary according to the region where they are found. Their specific weights are between 2000 and 2200 kg/m3. Natural pozzolans can be subjected to calcination operation. Thus, as a result of calcination, any carbonates in structures turn into oxygen components by disintegration. Natural pozzolans are divided into three sub-group as clays and sedimentary schists, opals and volcanic tuffs and pumice stones [15, 31, 32]. Synthetic pozzolans are pozzolans obtained by calcination operation. They are mainly industrial waste substances. Examples of such materials are silica fume from the manufacture of metallic silica and silica alloy, fly ash from thermal electric power plants, cinder from cast iron production in the iron and steel industry, and rice shell ash and corn stalk ash from agricultural residues [20, 33]. Examining Figure 3, in which the time and ash ratio-dependent change of water absorption in volume is given, it was understood that the water absorption of all groups displayed an increase depending on time and ash ratio. Figure 3 also provides equations to estimate water absorption in volume from exposure day as well as regression degree R2 which is very close to 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties.

The fact that water absorption in volume increased although mass change and capillary water absorption decreased with ash ratio cannot be attributed to the increase in active porosity. This situation does not fit the known correlation between water absorption in volume (active porosity) and permeability. The increase of water absorption in volume with ash ratio can be attributed to the adsorbing property of ash, whose specific surface is large, and to the carbon ratio within the ash [20]. However, it is shown that the total water absorption in volume increased although the substitution of WSA for cement is increased in the mortar, and the most probable pore diameter of the mortar shifts from a larger pore to a smaller one. In Figure 3, four polynomial equations are adopted to show the relationship between water absorption and exposure day. The degree of R2 is also provided in Figure 3 and shows a good compatibility between two specified properties. As the figure shows equations for the CBM, one may estimate a specified water absorption in volume by testing a specimen on at least one of the exposure days.

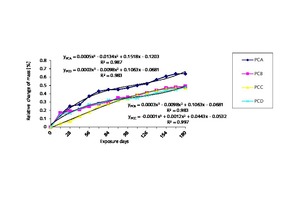

3.1.4 Capillary water absorption

Figure 4 also shows four important relationships between capillary water absorption and exposure day of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement, four mathematical equations, and four degrees of relationship as R2 which is very close to 1 meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties. Examining Figure 4, it can be seen that the capillary water absorption of groups with 8% and 24% wheat straw ash additive is lower than that of the group without additive at the beginning, and the capillary water absorption of groups with 8% and 16% additives is lower than that of the group without additive in the exposure days 90 and 208.

It can be said that ash interrupts their continuity by clogging capillary pores or it may have contracted the capillary pores. It can be concluded from this that the active ash ratio with regard to capillarity was 8% and 16% and that capillarity decreased in later ages. Evaluating Figure 3, it is noticed that the PCC shows the lowest capillarity at 208 days, and the second lowest capillarity is in the PCB. Additionally, the greatest capillarity is in the PCD, and the second greatest capillarity is in the PCA (Table 5 and Figure 4). However, it is shown that the total capillarity decreased as the substitution of WSA for cement increased in mortar up to 24%. Also, the most probable pore diameter of the mortar is reduced from a larger pore to a smaller one. In Figure 4, four polynomial equations are adopted to show the relationship between capillary water absorption and exposure day. The degree of R2 is also provided in Figure 4 and shows a good compatibility between two specified properties. As the figure exhibits equations for the CBM, one may estimate a specified capillary water absorption by testing a specimen on at least one of the exposure days.

3.1.5 Change of mass

Examining Table 5 as the time and ash ratio-dependent change ofmortar mass, an increase in mass was observed in all groups over time. However, the mass increase amounts are at a very small level. Figure 5 presents four important relationships between change of mass and exposure day of fresh mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement.

It also provides four mathematical equations and four degrees of relationship as R2 which is very close to 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties specified. Except for the group made of 8% wheat straw ash substitution for cement, two other ash-added mortar groups’ change of mass is lower than that of non-ash added mortar. Increases in mass in all groups showed a tendency to be stable after the 90 days. Considering the initial quantity, it is seen that the mass of change depends on the ash ratio in the mortar. The change towards decline in mass increase is connected to new chemical formations during the hydration process [19]. In Figure 5, four polynomial equations are adopted to show the relationship between relative change of mass and exposure day. The degree of R2 is also provided in Figure 5 and shows a good compatibility between two specified properties. As the figure provides equations for the CBM, one may estimate a specified change of mass by testing a specimen on at least one of the exposure days.

3.2 Mechanical properties

Table 6 gives types of experiment, types of mortar, averages and standard deviations of relative flexural strength and of relative compressive strength, and days of mechanical experiment.

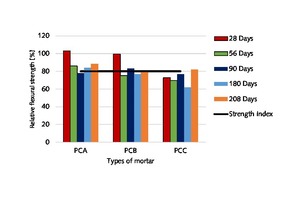

3.2.1 Flexural strength

Active elements contained in pozzolanic materials, such as SiO2, A12O3 etc., bind lime (CaO) that is one of the chemical compounds of cement and soluble in water, and thereby create calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which is insoluble in water. They reduce strength in the early ages due to the fact that pozzolanic materials reduce hydration heat and speed but considerably impact the ultimate strength. Pozzolans also increase durability by reacting with free lime. These particles, which are really small as they do not react with other chemical compounds of cement even if they are quite fine, increase compactness by serving as a passive aggregate, reduce pore size, prevent pore continuity by clogging capillary pores and lower the aqueous permeability. Figure 6 shows flexural strength, types of mortar, days of test, and strength index of mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement. The early age flexural strength of mortar samples with wheat straw ash additive, which is used as a pozzolanic material in this study, became lower than that of the ashless reference samples.

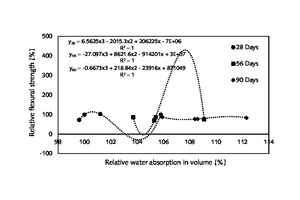

However, it was observed that flexural strengths in later ages increase in time depending on the ash ratio, and moreover reduce the water absorption in volume and the capillary water absorption. As shown in Figure 6, the time and ash ratio-dependent change of flexural strength is higher in mortars containing ash according to the strength index specified by ASTM C 618 standard. An increase is, albeit steady, seen in some ash groups in the early ages, while flexural strengths after day 56 remain at the same level on day 208. It is difficult to assess the ash’s influence on flexural strength. Examining the time and ash ratio-dependent change of flexural strength, a decline in flexural strength is observed in the early ages depending on the ash ratio, while it increased on day 208 in proportion with the ash ratio (Table 6 and Figure 6). For instance, flexural strength, which was 72.6% at first, reached 81.8% with an increase of 12.6% on day 208. Figure 7 presents three important relationships between relative flexural strength and relative water absorption of hardened mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement.

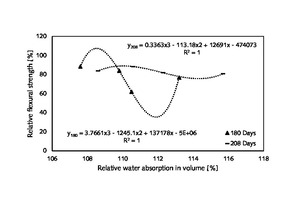

It also provides three mathematical equations and three degrees of relationship as R2 which is very close to 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties specified. Figure 8 demonstrates two important relationships between relative flexural strength and relative water absorption of hardened mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement.

In Figure 7 and Figure 8, five polynomial equations are adopted to show the relationship between relative flexural strength and relative water absorption. The R2 degrees, which show a good compatibility between two specified properties, are also provided in Figure 7 and Figure 8. As the figure presents equations for the CBM, one may estimate a specified relative flexural strength by testing relative water absorption of a specimen on at least one of the exposure days.

3.4 Relative compressive strength

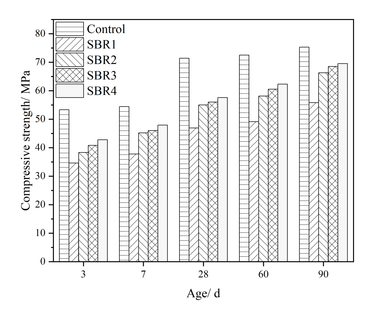

Lightweight cement based composites have been used properly in various structures such as dam bodies, buildings, and bridges for many years. One of the best practices was in the construction of cement mortar ships in North America between 1914 and 1918 [34]. Throughout the years, by proper mixing design and selection of the mild sand, semi-lightweight cement mortars possessing great compressive strengths were produced for evaluation purposes [35]. Even though such strength gain is not important in many structural members, there are benefits to the use of semi-lightweight cement mortars in such applications as offshore drilling platforms. Such lightweight cement based material has greater floating ability and is thus easier to push and tow in shallow sea water, and less excavation is required in the construction of the dry platform when compared to heavier constructions. There is one enterprise where such lightweight CBM has been used for oil-drilling platforms in the Arctic [36]. Additionally, such lightweight CBM permits savings in dead load and thus reduces the cost of both superstructure and foundations, is resistant to fire and provides greater heat and sound isolation than a CBM of normal density [37, 38, 39]. For lightweight CBM constructions, there is a well-set trend toward using greater compressive strength gain than for a structure made of normal weight CBM. Figure 9 shows compressive strength, types of mortar, days of test, and strength index of mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement.

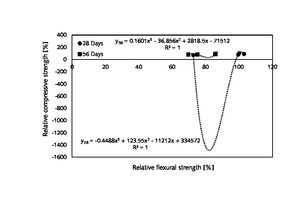

This use allows the building of structures with small structural members because of the enabled decrease in dead load, resulting in cost reductions and increases in the practical distance between structural columns [40, 41, 42]. The main aim of the section described in this manuscript was to contribute insight regarding the compressive strength gain of lightweight cement mortar reinforced with wheat straw ash. The early age compressive strength of mortar samples with wheat straw ash substitution, which is used as a pozzolanic material in this study, was lower than that of the ashless reference samples. However, it was observed that compressive strengths in later ages increase in time depending on the ash ratio. As will be understood from Table 6 and Figure 9, the time and ash ratio-dependent change of compressive strength is higher in mortars containing ash according to the strength index specified by ASTM C 618 standard. An increase, albeit steady, is seen in some ash groups at the later age of 208 days, when compressive strengths are greater than those of 28 days. This is an indicator regarding the ash’s influence on the compressive strength of lightweight cement mortar containing wheat straw ash. Examining the time and ash ratio-dependent change of compressive strength, while a decline is observed in compressive strength on days 28, 56, and 90, depending on the ash ratio, it increased on day 208 in proportion with the ash ratio (Table 6 and Figure 9). Figure 10 presents two important relationships between relative compressive strength and relative flexural strength of hardened mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement.

For instance, compressive strength, which was 71.2% at first, reached 106.8% with an increase of 50% on day 208 although it was made of 76% common cement and 24% wheat straw ash. In other words, even though it contains a 24% lower cement amount, the compressive strength of PCD gives a similar compressive strength amount with PCA which is the reference mortar at 208 days. Figure 11 presents three important relationships between relative compressive strength and relative flexural strength of hardened mortar made of wheat-straw-ash-added cement and common CEM I 42.5 N cement. Figures 10 and 11 also present five mathematical equations and five degrees of relationship as R2 which is very close to 1, meaning that there is an important indicator for a forceful relationship between the two properties specified.

In Figures 10 and 11, five polynomial equations are adopted to show the relationship between relative compressive strength and relative flexural strength. The R2 degrees, which show a good compatibility between two specified properties, are also provided in Figures 10 and 11. As the figure presents equations for the CBM, one may estimate a specified relative compressive strength by testing the flexural strength of a specimen on at least one of the test days.

4 Conclusions

As a result of the examinations carried out above:

The specific surface of wheat straw ash is smaller than that of cement and binds free lime, which is the product of cement hydration, due to its active silica content. Also the non-reacting ash particles reduce the porosity by serving as a passive aggregate

The early-age strength declines in mortars produced with wheat straw ash with pozzolanic property, which causes an increase in later-age strength

In addition to binding lime, which is a hydration product, wheat straw ash also reduces pore size by serving as a passive aggregate, clogs capillary channels and lowers the capillary water absorption by reducing the capillary continuity

Mathematical models presented in the manuscript ease the laboratory workload for determining the physical and mechanical properties

Wheat straw ash burned at 670 ºC was used and the experiment duration was limited to 208 days. It will be interesting to perform longer experiments with ash obtained at different temperatures.

Acknowledgement

In this study, the cement factories, Akçansa A.Ş., Pınarhisar A.Ş. and Sika are gratefully acknowledged for their provision of material.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.