The leaching of antimony from concrete

The use of antimony compounds as reducing agents for hexavalent chromium has proved to be the best solution regarding long term reduction, absence of negative impacts on cement quality and cost effectiveness.

1 Chemistry of antimony in aqueous media

It can be expected that antimony compounds are readily soluble in the alkaline environment found in concrete pore water, but actually the situation is different due to interactions between antimony and the cement hydration products. Calcium antimonate (the solubility product of which was calculated and is K = [Ca2+]·[Sb(OH)6-]2 = 10-12.55 [4]) has a very low solubility, thus the high calcium availability in cement-based systems should reduce the leachability of antimony.

In addition, investigations of the antimony leaching from incinerator solid waste as a function of pH and carbonation [5] showed that at alkaline pH the Sb leaching is lower than that expected on the basis of the solubility product of calcium antimonate. Calcium bearing minerals such as portlandite and ettringite probably play an important role in controlling Sb leaching.

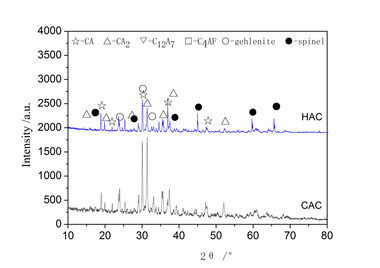

When cement is mixed with water, antimony trioxide dispersed in cement goes rapidly into solution following the pH increase. After red-ox reaction with hexavalent chromium, antimony is basically present as Sb(V), probably fixed in hydrated cement paste as calcium antimonate. If Sb(III) partially remains, this can be included as calcium antimonite or in AFm phases, following its similarities with Al(III). Recent papers discuss in more detail possible immobilization pathways [6].

2 Leaching of antimony from concrete

The use of analytical techniques (ICP/AES) with 10 µg/l Sb as lowest detection limit is suitable only for a first assessment of antimony leachability. The target of this paper is to provide further investigations considering the limits of antimony in drinking water, that are set to a maximum of 5 µg/l (ppb) by the European Union [8].

3 Experimental part

For each cement reproduced, concrete (340 kg/m3, class XC4 according to EN-206) was mixed and cast in several 10x10x10 cm cubic specimens. The water cement ratio was kept constant (w/c=0.5) and a standard acrylic based superplasticizer was used. The cubes were cured (wrapped in plastic foil as a form of protection against accidental contamination) for 56 days at 20 ± 2 °C and >90 % RH before starting the leaching test. In addition, cement with 1000 ppm antimony trioxide was used for preparation of a cement paste (W/C=0.5), cast and cured in the same way as the concrete specimens.

Thus, leaching from concrete and cement paste cubes was evaluated through tank tests conducted using an internal method based on NEN 7375:2004. Cubes were immersed in the leachant (liquid volume/surface area of cube 80 l/m2) and kept in static conditions at 21 ± 1 °C. Several leachates were collected: the liquid was separated, the pH and electrical conductivity were measured, acidified (with HNO3 1 % + HF 0.1 %) and stored for analysis, then replaced with the same amount of fresh water. For each test performed, a blank test was run.

Apart a slightly different choice of the intervals, the difference between the internal method of the present study and NEN 7375:2004 lies in the leachant. We decided to use tap water, rather than distilled water (or distilled water corrected with nitric acid until pH = 4, as described in NEN 7345:1995) in order to have a situation similar to the real conditions of concrete in contact with drinking water. Some tests focused on a comparison of the difference between tap water and leachants described in NEN 7375 and NEN 7345. A summary of these leaching tests is reported in Table 1.

The antimony determination in leachates was performed with ICP/MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma/Mass Spectrometry) analysis at the University of Barcelona using an ICP Perkin Elmer Elan 6000. Calibration was performed with five standards (Sb 1 g/l NIST traceable) prepared with nitric acid/hydrofluoric acid and using rhodium as internal standard. The lower detection limit for antimony in this matrix was found to be 0.5 µg/l (ppb). Some leachates were analyzed for other elements (such as K and Na) using ICP/AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma/Atomic Emission Spectrometry Varian Vista MPX Axial).

4 Results

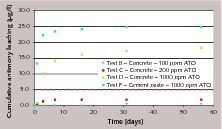

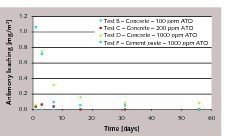

Leaching seems to be directly related to the antimony content in cement. Passing from cement with 100 ppm ATO (where there is little or no detection of antimony in water) to cement with 1000 ppm ATO, the antimony leaching increases.

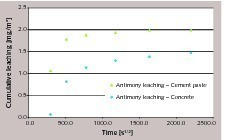

Antimony release is faster during the first few days of contact with water, then rapidly decreases or completely stops. This is very clear in the case of concrete or cement paste prepared with cement containing 1000 ppm antimony.

Leaching from cement paste is higher than from concrete. This can be related to the fact that a 0.5 w/c paste contains a higher amount of cement (around 1400 kg/m3) than a 340 kg/m3 concrete prepared with the same cement, and consequently higher antimony is available for leaching.

According to the test summarized in Figure 1, the limit of antimony in drinking water is exceeded when very high amounts of antimony trioxide are involved. Dosages of up to 200 ppm in cement still provide concrete with leaching below 5 ppb Sb.

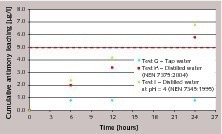

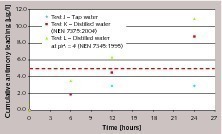

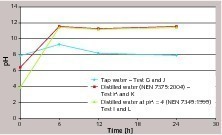

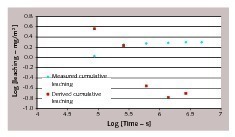

Figure 4 (tests G, H and I, cement with 100 ppm ATO) and Figure 5 (tests J, K and L, cement with 200 ppm ATO) demonstrate the effect of different leachants: cumulative antimony leaching profiles obtained in tap water, distilled water (according to NEN 7375:2004) and distilled water corrected with nitric acid to pH = 4 (according to NEN 7345:1994) are compared.

The results show evident differences in leaching behavior: distilled water seems to promote a release of antimony that does not slow down after the first intervals, but increases and rapidly (especially at higher antimony trioxide contents in cement) exceeds the 5 ppb limit. As already pointed out in NEN 7375:2004 (see Annex B), the use of distilled water corrected to pH=4 as leachant can largely increase initial leaching, especially with material with low buffering capacity. Although concrete (due to alkalinity of cement paste) tends towards a rise in the pH of water (thus acting as buffer), higher amounts of antimony released are noticed when acid leachant is used.

A possible explanation for this different behavior can be derived from the pH variation (Fig. 6). Tap water has a buffering effect on the pH value (probably due to the presence of calcium salts that, for equilibrium reasons, slows down the dissolution of portlandite and calcium silicates hydrates), that remains around 7.5–9 (average pH: 8.5 ± 0.7) at all intervals. With distilled water (where no salts are present, thus promoting the dissolution of cement paste) the pH level is stabilized at 11.5 ± 0.2. This type of difference in the pH can strongly affect the leaching of the antimony, probably as a consequence of a different stability of antimony bearing phases. Thus, this different behavior should be taken into account when considering leaching in drinking water.

5 Discussion

Leaching from concrete can be governed by diffusion, dissolution (the element is released due to its solubility in the conditions of the test) or decomposition of phases (hydration products decompose allowing the release of an element previously immobilized).

Diffusion processes are described by Fick’s laws, that can be summarized (for diffusion in one dimension, e.g. x-axis) as follows:

J is the flow of the diffusing species (mass/surface · time)

D is the diffusion coefficient (surface/time)

dC/dx is the variation of the concentration of the diffusing species in the x direction (mass/volume · length)

dC/dt is the variation of the concentration of the diffusing species as a function of time (mass/volume · time)

E is the cumulative leaching as a function of the surface area (mg/m2)

r is the density of concrete (kg/m3)

Q is the total availability of the element leached (mg/kg)

D is the diffusion coefficient (m2/s)

t is time (in seconds)

When concrete prepared with cements containing 100 and 200 ppm ATO are considered, antimony contents in leachates are quite low and comparable with the lower detection limit of the analytical method, thus it is not possible to evaluate the leaching mechanism.

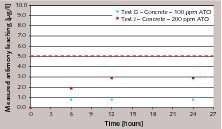

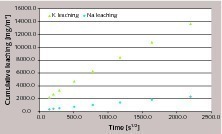

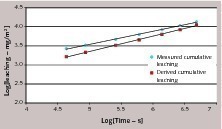

Alternatively, if we consider concrete and cement paste containing overdosed amounts of antimony (tests D and F), the graph representing cumulative leaching versus square root of time is reported in Figure 8 and it can be clearly seen that the relation is not linear. It must be mentioned that Figure 7 and Figure 8 should not be directly compared, as different leachants are involved. However, the data in Figure 8 suggest that when antimony leaching in tap water is considered, the general behavior is far from a diffusion controlled process.

NEN 7375:2004 makes use of the same correlation with the square root of time. In order to assess whether leaching is diffusion controlled, a quantity defined as derived cumulative leaching is calculated as follows:

«n is the derived cumulative leaching after period n (mg/m2)

Ei is the measured leaching in leachate at interval i (mg/m2)

ti is the time of interval i (s)

Boundary conditions of the semi-infinite slab model require that the concentration of the diffusing species at the interface concrete/leachant is constant [10]. This approximation is fulfilled when its availability in concrete is much higher than quantity diffused in water. In the case of antimony, we can suppose that diffusion from the core of the concrete to the surface is much slower than diffusion from the concrete surface to water. Hence, after initial leaching of the antimony in the external layer of concrete the process slows down or is interrupted because no further antimony is supplied to the interface.

6 Conclusions

Nevertheless, according to the results we obtained, it seems that at dosages normally used in industrial practice the amount released is very low, at least for the majority of the cements normally produced (the soluble chromates content of which hardly exceeds 15 ppm).

The fact that antimony leaching (at least at dosages considered in the present study) is not described by pure diffusion has some important consequences. In fact, diffusion is basically controlled by the difference in chemical potential and driven by differences in concentration between solid and liquid phase. On the other hand non-diffusive mechanisms (thus involving dissolution or chemical modifications) are more sensitive to pH. This means that the use of distilled water as leachant is not comparable to tap water and care must be taken in case the target of the leaching test is the reproduction of real conditions on site (where distilled water is never used).

Finally, we would like to point out that a mechanism (such as the one we described in the present study) where leaching rapidly slows down or stops after the first hours of contact with water should allow the limitation and control of the eventuality of antimony release, by following the proper pre-treatment procedures of the concrete.

Acknowledgements

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.