Hydration investigation of α-calcium

sulphate hemihydrates is influenced by waste water from the foundry sand

regeneration process

The influences of waste water collected from the wet regeneration process of foundry sand on the hydration of α-calcium sulphate hemihydrates (α-HH) was investigated. The characterization of liquid phase and solid phase in the waste water was conducted using ion exchange chromatography (IC), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Phosphate was found in waste water by IC, which severely retarded the setting times of plaster slurries. The compressive strength and density of gypsum was increased with addition of waste water. The pore size distribution was shifted to a higher range in deionized water in comparison with waste water containing samples. These results were obtained by means of gas adsorption (GA) and mercury intrusion porosity (MIP) methods accordingly. Moreover, the microstructure of the samples was investigated by utilizing SEM. The degree of hydration was investigated by using quantitative XRD and simultaneous thermal analysis (STA), respectively.

1 Introduction

Foundries use sands to make moulds and cores for metal casting. In this process, new sands are mixed with a diversity of inorganic and organic binding agents such as clay or organic chemical binders or resin [1]. From the resultant mixture, moulds and, if required, cores are prepared. The molten metal, at a temperature above 1000 °C, is cast into the molds [2], then left to harden, cool and, finally, to be removed. New sand is sporadically added to the system in order to maintain optimal molding characteristics. The excess sand that is generated during casting is dumped in...

1 Introduction

Foundries use sands to make moulds and cores for metal casting. In this process, new sands are mixed with a diversity of inorganic and organic binding agents such as clay or organic chemical binders or resin [1]. From the resultant mixture, moulds and, if required, cores are prepared. The molten metal, at a temperature above 1000 °C, is cast into the molds [2], then left to harden, cool and, finally, to be removed. New sand is sporadically added to the system in order to maintain optimal molding characteristics. The excess sand that is generated during casting is dumped in landfills as surplus foundry sand [3]. The sand cores are necessary to create openings in the castings. Different organic binders are used for preparing the core. The typically employed chemical binders are phenolic urethane resin, furfuryl resin, sodium silicate, etc. Various catalysts and materials are used for gaining better surface quality of casting and core. Due to the exposure of these binders and additives to elevated temperatures, the majority of them will burn down. The mould and core sands are reused at the foundry a number of times, i.e., until they wear out due to mechanical abrasion during the moulding process, and are then disposed of in landfills. These discarded sands are called surplus foundry sand, waste foundry sand or spent foundry sand [4]. Apart from this, many moulds and cores rejected during the quality inspection test and discarded in landfills are also termed surplus foundry sands. Surplus foundry sands that are not exposed to high temperatures can contain a wide variety of organic and inorganic chemicals. Boyle et al. (1978) [5] stated that a higher organic binder level in the surplus foundry sand is due to the higher percentage of cores used and to the type of metal cast.

Population growth and advancements in technology have led to increasing waste production. Thus, many researchers and scientists all over the world are finding new ways to reduce these wastes or, as a better alternative, to use them as resources with value added [6-8]. Over the past several decades, various types of industrial waste have been studied extensively as substitute/replacement material for fine aggregate in building materials. Substitution of alternative materials in construction material has been found to improve both the mechanical and durability properties, and this practice can promote the development of sustainable material systems. Waste foundry sand (WFS) is one such promising material that needs to be studied extensively as a substitute for fine aggregates in construction materials. As already mentioned, it is a by-product of the ferrous and non-ferrous metal casting industries with ferrous foundries producing the most sand. It is characteristically sub-angular to round in shape and displays high thermal conductivity, making it suitable for molding and casting operations. Molding sands are recycled and reused multiple times during casting processes. In due course, the recycled sand degrades to such an extent that it can no longer be reused in the casting process. At that point, the old sand is discarded as a by-product, and new sand is introduced into the cycle [9-11].

The regeneration of used sand is very important for the foundry industry, because it reduces the demand for new sand and cuts the relevant costs for the industry. Furthermore, waste reduction is another very important factor, since waste disposal is expensive and likely to exacerbate environmental pollution. There are three primary methods of foundry sand regeneration: thermal regeneration, dry regeneration and wet regeneration. Within the foundry industry, combinations of different methods are used.

Wet regeneration, a method for removing the residuals by means of dissolution and mechanical stirring of water, is suitable for application to water-glass-bound foundry sand. The advantage of wet regeneration is that it has a good regeneration effect for sand with water-soluble binders, and the reclamation quality is high. The disadvantage is that waste water is produced as a useless byproduct.

To solve the problem of waste water, the first step is to introduce a water treatment system en-abling the water to be reused in the wet regeneration process. On the other hand, this waste water also serves to generate added value. In this research, waste water from the foundry sand regeneration process is characterized by different analytical methods, and the relevant influences on α-hemihydrate hydration system are investigated.

Gypsum is one of the most used materials in the world; 263 million tons of natural gypsum were won worldwide in 2016 [12]. Additionally, there are another 300 million tons of byproduct gypsum coming from various production processes for phosphoric acid, citric acid and hydrogen fluorine, for example, and from flue gas desulfurization.

Calcium sulphate-based binders and gypsum are used for very different technical applications like floor pavement, stucco and plasterboard in the building industry, casting in the ceramic industry, as an additive in polymers and colors or for plaster bondage or dental casting material in the medical sector, and as a food additive, either for human consumption (e.g. in ketchup or tofu) or in animal food. The principal customer is the cement industry, where calcium sulphates are in use to retard the very fast reaction of the clinker phase aluminate C3A, which consume 51 % of the gypsum, and for calcium sulphate-based binders in the building industry, where another 39 % is used [13].

Another question is which phenomena occur during the reaction of calcium sulphate hemihydrate with water to yield calcium sulphate dehydrate:

2 CaSO4 • 0.5 H2O + 3 H2O = 2 CaSO4 • 2 H2O⇥ (1)

In the literature, different theories are considered. The growth of gypsum crystals out of a supersaturated liquid was described by Lavosier and Le Chatelier in 1919 [14-15]. Cavazzi and Traube [16] described a gel-like interface and the stepwise transformation of dihydrate into a crystal form. Another kind of reaction was published by Fiedler (1958). He described the crystallization of gypsum as an inner reaction in the calcium sulphate subhydrates by an inner transformation of the crystal structure. Perederji in 1956 [14] and Eipeltauer [18] in 1960 combined the theories of Lavosier and Le Chatelier and Fiedler and published their view that an inner hydration process takes place along with the creation of dihydrate out of a supersaturated solution.

2 Materials

A sample of combined waste water (WW from mechanical mixing + washing) was taken from the wet regeneration process of foundry sand, diluted for the calibrated ion concentration range of the ion chromatograph, and subjected to anion/cation analysis, respectively. The results of anion analysis are shown in Table 1 below for an integrated 1.15 % CaO treated water. The considerable amount of phosphate which is found in the waste water, approached zero when the waste water was treated with 1.15 % CaO as solid content. The stated amounts in ppm correspond to the values of mg/l. In the case of a concentration of wash water to a gel-like consistency, the contents increase correspondingly. By way of comparison, the results of cation analysis are shown in Table 2 below.

The significant sodium content stems from the sodium water glass, which is used as binder for molding purposes in the foundry industries. The potassium and calcium contents are also higher in comparison with others that can also impact the hydration of α-hemihydrates (α-HH).

The residue, which is evaporated to dryness, was finely ground, transferred to a melting tablet and analyzed for its oxide constituents (chemical composition) by means of X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF). Table 3 shows the proportions of the corresponding oxides in % by weight as well as the loss on ignition (LOI) of the sample, also in % by weight. The loss on annealing is caused chiefly by the dissolution of carbon during the washing process and by the SiO2 concentration, which is high in comparison to that of Na2O due to fine sand particles entering the wash water via the sieve.

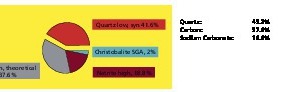

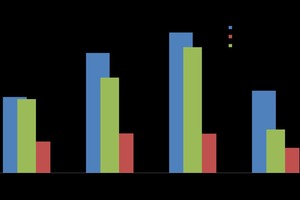

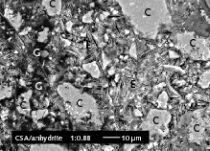

For qualitative phase determination (determination of crystalline constituents) of the residue of the wash water evaporated to dryness, the sample was examined in a powder diffractometer using Cu-Kα1,2 X-ray radiation. The X-ray phase analysis is performed by search-match identification using the ICDD’s PDF-2 database (International Center for Diffraction Data). The residue was ground to <63 μm and transferred to the sample carrier in a back-loading process, and the measurement was then carried out. Figure 1 shows the results of semi-quantitative analysis of the residue in mass percent. The main constituents were carbon (diamond), which was washed off during the regeneration process, SiO2 in the form of quartz and cristobalite through the fine sand particles, which enter the wash water via the sieve, and identify as sodium carbonate (natrites). Non-crystalline components were not included in this analysis.

The quantitative XRD results show the amount of anhydrates (8 %) and bassanite (90.9 %) which is a major constituent of the α-HH.

3 Results and discussions

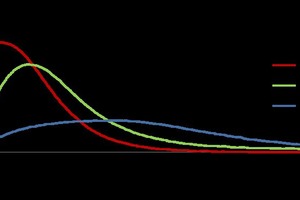

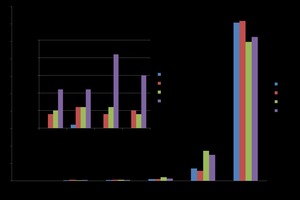

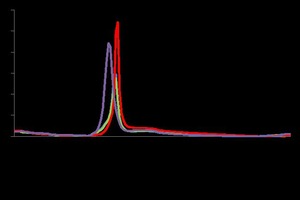

The influence of the waste water on heat development during hemihydrate hydration (reaction of hemihydrate with water) was investigated to explore the possibility of using waste water in gypsum based binder systems. A reduction in maximum heat development and a retarding effect on the reaction of an alpha-hemi-hydrate (α) with water were demonstrated (Figure 2), as in the investigation of the gypsum systems.

The abbreviations WW and CWW stand for waste water and concentrated waste water.

The hydration of α-hemihydrate was observed by heat evolution with replacement of the deionized water with waste water (WW) with retarded hydration becoming even slower in the case of concentrated water (CWW, 50 w/w% concentrated by heating at 80°C). The investigation charted the progress of hydration of α-hemihydrate (α-HH) as similar to P2O5 content in the water. The waste water has more retardation effect as compared to P2O5 content in the water.

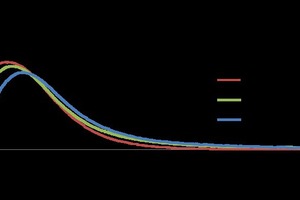

There is no influence on hydration when the waste water is treated with CaO. As a result of CaO treatment of the waste water, no phosphate content was detected by IC investigation. The reason for the higher heat flow is the higher calcium ion concentration compared with the reference (Figure 4). So, the cause of retardation, in addition, was the waste water in α-HH due mainly to the presence of phosphate.

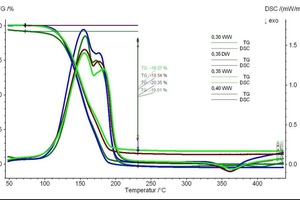

The α-hemihydrates gypsum stone samples were produced for the flexural strength and compressive strength measurements. These samples had a size of 15 x 15 x 60 mm. The samples were stored for 1 day at room temperature and 1 day at 60°C. Additionally, samples were designed for water-to-hemihydrates ratios of 0.30 WW, 0.35 WW, 0.40 WW and 0.35 DW (deionized water) (as a reference).

It has been found that a higher 2-day compressive strength is achieved in combination with a higher density. Figure5 shows the results for different water / α-HH values (0.3 - 0.4) when using wash water compared to a reference sample with deionized water (DW (R)).

The formation of hydration products yields gypsum as an indication of both the degree of hydration and of strength. The percentages established for gypsum are higher than for DW. The flexural strength increases by a small fraction for all samples containing waste water, and the highest compressive strength was found for the 0.35 WW sample.

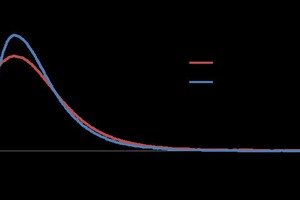

As the percentages of gypsum are one indication of the degree of hydration, this can also be compared with the TG values from thermal analysis. The TG curves have been presented in such a way as to correlate the degree of hydration with the loss of water. 0.35 DW showed less weight loss as compared to the others (Figure 7).

The waste water based samples showed nearly 21 % water loss, which is typical within the hemihydrates system. On the other hand, the deionate based water showing 18.54 % water loss also correlates with the quantitative XRD analysis data.

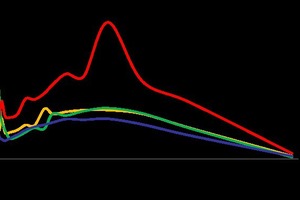

The BET surface area of the 0.35 DW (2.18 m2/g) is higher compared to waste water base systems (1.03, 1.16 and 1.09 m2/g for 0.30, 0.35 and 0.40 WW, respectively), as analyzed by gas adsorption (GA). It is indicated that the corresponding pore size distribution is higher than the others. The BJH methods also specify correlation with the BET methods (Figure 8).

The hemihydrates yield comparatively larger crystals than does the cement system. So, mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was used to verify the porosity of all 2-day hydrated samples. The porosity was determined to be 30.76, 24.52, 25.36 and 33.35 % for 0.30 WW, 0.35WW, 0.40 WW and 0.35 DW, respectively. The differential pore volume increased with respect to pore radius in comparison with waste water gypsum stone (Figure 9).

The pore size distribution found according to both methods (GA and MIP) showed correlation between pore volumes with respect to pore width and radius. In contrast, the porosity was lower and the density higher with respect to the deionized water sample, which also correlated with the strength of the waste water gypsum stone samples.

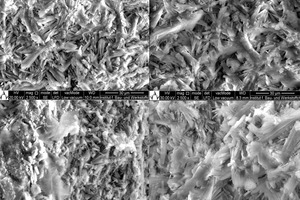

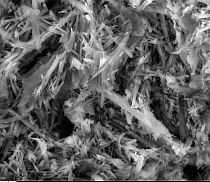

The microstructures seen in the SEM images were obtained after 2-day hydration of gypsum stone in the presence and absence of waste water (Figure 10). The hydrated crystal size was found to be smaller and non-uniform regarding the deionized water sample compared to waste water samples. On the other hand, some unreacted products were found in deionized water. The increasingly clear crystal morphology of the reaction products observed for denser structures and higher strengths was due to better interlacing of the reaction products in waste water containing samples.

4 Conclusion

Waste water influences the hydration of hemihydrate, the different technical properties of the resultant gypsum stone and the morphology of the single dihydrate crystals. One main effect which was investigated is the retarding effect of waste water. The retarding effect of phosphate-containing waste water on the setting of gypsum could be explained in relation to the absence of phosphate in CaO treating waste water, which was determined separately in a DCA experiment. These data allowed quantification of the phosphate effect at various stages of the setting process. HH dissolution, calcium sulfate dehydrates (DH) nucleation and DH growth at high degrees of supersaturation are diffusion controlled processes. Retardation of their reaction kinetics may be due to covering of the surface of HH by waste water containing phosphate or a small amount of silica, which governs the resultant diffusion properties. However, during the phase of simultaneous HH dissolution and DH growth, the retardation effect becomes significant, and as both processes are diffusion controlled, the diffusion properties and the associated phosphate covering the surface of HH from waste water play a key role. On the other hand, it also increases the strength of the gypsum stone thus created. The formation amount of DH as a hydration product was also found to be higher in waste water containing samples with different water to the α-HH ratio as compared to the reference, and it occurs when the curing time and temperature of gypsum stone are identical. It is remarkable, that waste water increases the strength of gypsum stone created by the hydration of hemihydrate in the presence of waste water.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.