1 Introduction

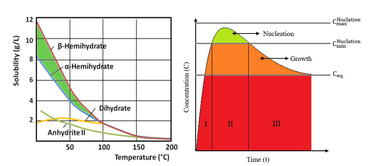

The development of the mechanical properties in ordinary Portland cement is closely linked to the hydration of tricalcium and dicalcium silicates. Accelerating the hydration of these phases, and therefore the setting and hardening of concrete, is highly desired in many applications, mainly for speeding up the production or to reduce the cement portion in the concrete mix design. The addition of seeds, namely the “seeding”, is a common practice to accelerate and control the crystallization and in this case to accelerate the cement hydration. Despite the fact that this idea is not new [1], its introduction on to the market and thus the technology are quite recent. Indeed, a suspension of finely dispersed calcium silicate hydrate particles (X-SEED®100) was commercialized by BASF. These C-S-H nanoparticles develop a large surface area, and this is the main difference compared to other seeds from the past. Also, in the literature, studies have shown the potential of this technique for accelerating alite and cement hydrations [2,3] as well as the hydration of slags [4]. The efficiency of the seeding technique is less sensitive to the cement composition compared to other regular accelerators. However it does still influence the performances of the seeding particles. The silicate hydration in paste (water to cement ratio inferior to 1) consists of 3 steps:

1) �There is an extremely short period of pure dissolution until the ion concentrations reach the maximum supersaturation with respect to C-S-H:

Ca3SiO5 → 3Ca2+ + H4SiO4 + 6OH–⇥(1)

2) �As soon as the maximum supersaturation is reached, the first C-S-H particles mostly nucleate heterogeneously onto the C3S grains.

1,5 Ca2+ + H4SiO4 + 3OH– → C1,5 – S – H3,5⇥(2)

3) �After the rapid C-S-H nucleation, the concentrations evolve slowly: the system is in the steady state. The first C-S-H particles will grow and meanwhile C3S continues dissolving: dissolution and precipitation are simultaneous. The kinetic path followed by the Ca2+, OH- and H4SiO4 concentrations is located between the solubilities of C3S and C-S-H [5].

In this study, for a pragmatic approach, we first looked at mathematical correlations between the main cement characteristics and the acceleration by seeding. We also tried to define mechanisms explaining those correlations. Secondly, as the addition of seeds allows us to directly control the initial surface area of nucleation, we may shed a new light on the silicate hydration.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

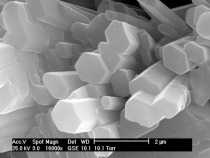

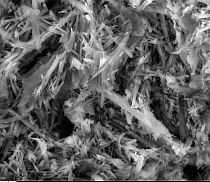

Seven different cements and two alites were considered in this study. The phase composition determined by Q‑XRD, the solid elemental composition by XRF as well as the pore solution compositions during the first minutes are reported in Table 1. The C-S-H suspension used in this study is X-SEED®100 produced by BASF. The dosages are given in percentage of dried C-S-H with respect to the mass of cement powder.

2.2 Calorimetry and processing of calorimetry curves

50g of cement and 25g of distilled water are mixed by mechanical stirring. Then, 3g of paste is sealed in a plastic ampule and inserted into the calorimeter (TAM‑AIR, TA Instruments). For pure alite systems, the quantities are reduced to 3g of alite mixed manually with a spatula. The temperature is kept steady at 20°C. All hydrations were carried out with water to cement/alite ratios of 0,5.

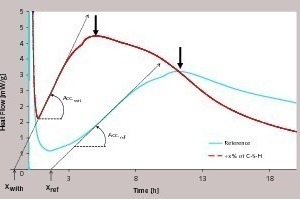

A linear heat flow evolution occurs during the first hours of hydration (Fig. 1). As the heat flow is proportional to the hydration rate of silicate phases, the derivate of heat flow with respect to time represents the hydration acceleration. The linearity means that the acceleration is constant, and defined by the slope Acc.ref for reference, and by Acc.with CSH when seeds are present. The relative acceleration A, due to the addition of C-S-H seeds, is calculated as follows:

A = Acc·withCSH⇥(3)

Acc·ref

The time frame of the low activity period, often referred to in the literature as the “dormant period” is characterized here by the parameter X (see Fig. 1).

3 Experimental results

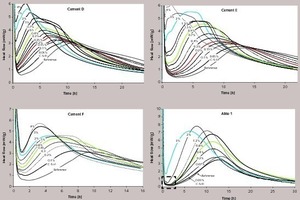

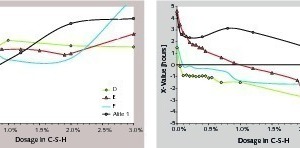

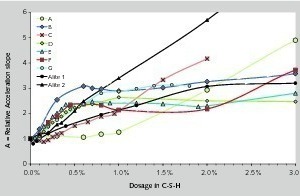

All cements and alites were hydrated with various amounts of C-S-H up to 4%. In Figure 2 4 examples of the principal behaviors encountered in our experimental set are shown. Then, the relative accelerations A and X-Values are reported in Figure 3 for the same cements and alite.

Basically, 4 types of accelerating behaviors can be identified. (1) A small addition rapidly reduces the “dormant period”, then the acceleration increases until reaching a plateau (cement D); (2) The hydration is further accelerated with a higher dosage of C-S-H (cement F); (3) sometimes the dormant period is not completely suppressed (cement E); and (4) finally the hydration of pure alite shows an immediate increase of the acceleration, still combined with a long dormant period. The evolutions of relative acceleration A for all cements are shown in Figure 4.

4 Discussion

In the steady-state, the hydration of C3S consists of the simultaneous dissolution of C3S and precipitation of C‑S‑H, it implies an equalization of the rates:

RHyd. = RC3Sdiss. = RCSHprec.⇥(4)

The reaction rate, either of dissolution or of precipitation, is the product of the corresponding interfacial reaction rate with the surface area of dissolution or precipitation:

RiCSHSCSH = RiC3S SC3S⇥(5)

which yields

RiC3S (t) = SCSH (t) (6)

RiCSH(t) SC3S (t)

We may define a reference state, indexed with 0, and an accelerated state indexed with 1. At low changes in ion concentrations, there is equivalence between the volume evolution and the surface evolution. Therefore, there is an acceleration of the hydration if and only if:

S1CSH(t) > S0CSH(t) and S1C3S(t) < S0C3S(t), it yields:

S1CSH(t) = S0CSH (t) (7)

S1C3S(t) S0C3S (t)

Based on equation 6, this implies that there is acceleration if and only if:

RiC3S1(t) > RiC3S0(t) (8)

RiCSH1(t) RCSH0(t)

The interfacial rates are monotonic continuous functions of the deviation from equilibrium, i.e., the undersaturation regarding the C3S dissolution (bC3S) and the supersaturation for the C-S-H precipitation (bCSH):

RiC3S(t) = ƒ (bC3S) and RiCSH(t) = g (bCSH)⇥(9)

The function ƒ (bC3S) was recently fully determined [6] and obeys a very classical law encountered elsewhere [7]. It is quite reasonable to assume that C-S-H growth also follows a similar law. In general terms , we write the interfacial rates in function of the ion activity products involved in the reactions of dissolution and precipitation:

RiC3S(t) = ƒ((Ca2+)3(OH–)6(H4SiO4) / KC3S) (10)

RiCSH(t) = g((Ca2+)1,5(OH–)3(H4SiO4) / KCSH)

The silicates species being the limiting species and combining equations 10 and 8, the acceleration of the hydration is possible if and only if:

((Ca2+)·(OH–)2)1 < ((Ca2+)·(OH–)2)0 (11)

This is quite a general condition for the acceleration of hydration. By seeding, we add at the beginning a further constraint on SCSH. The kinetic path followed during the hydration in the presence of seeds, if the system is able to accelerate, has to depart from the kinetic path followed in the absence of seeds. This deviation has to favor the dissolution of C3S and disfavor the precipitation of C-S-H, i.e. it has to favor the lower calcium hydroxide concentrations, as imposed by Equation 11.

The following observations established from the evolution of the acceleration curves are summarized in 5 points:

4.1 The simultaneous acceleration of the aluminate reaction:

It is remarkable that for all cements, the sulfate depletion characterized by a peak in the respective calorimetric curves (see Fig. 1) is also accelerated. This can be reasonably explained by the fact that the presence of C-S-H seeds accelerates the dissolution of C3S and therefore the flow of calcium and hydroxide ions which in turn contribute also to the acceleration of the aluminate hydration.

4.2 Evolution of the early period of low activity

For most cements, the addition of synthesized nuclei first shortens the “dormant” period and then accelerates the hydration. That this is not an absolute rule can be seen with cement F and alite 1. In these cases, the duration of the dormant period remains relatively long although huge quantities of nuclei were added. This is particularly clear for the alite 1 which does not contain any phases other than C3S. The result of this observation is that the phenomena leading and ending the dormant period are certainly not only due to the nucleation of C-S-H but likely to the nucleation of C-S-H and dissolution of C3S. Additionally, it is not possible in this case to invoke the precipitation of metastable C-S-Hm [8] which by protecting the surface of C3S, leads to the dormant period: the most stable hydrate, C-S-H, already being present. Theories regarding the “dormant” period where C-S-Hm are involved, are contradicted by our experiments.

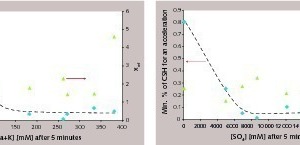

4.3 Annihilation of first nuclei

In some cements, significant dosages of C-S-H seeds are required to initiate the first acceleration of the hydration. This means that, below these dosages, the first C-S-H seeds are inefficient or annihilated. Looking at possible parameters likely to be correlated with this phenomenon, we saw that the alkali concentration and/or the sulfate concentration are the most relevant (Fig. 5). In cement, both parameters are strongly interconnected since they are dependent on the alkali sulfate content. We observed that, if those are too low, a lot of C-S-H is needed for the first acceleration. In the same figure, there is no clear correlation between the quantities of annihilated nuclei and Xref, i.e., in references the alkali and/or in sulfate concentrations do not directly influence the dormant period. For both alites, the hydration is rapidly accelerated, whereas there are no alkali sulfates. This leads to the conclusion that the annihilation of C-S-H nuclei in cement should be connected with (1) the presence of aluminate phases and (2) the interplay with the alkali sulfates. Remembering the previous point, it can be assumed that the hydration of aluminate phases is of great importance in the C3S dissolution and/or in the C-S-H nucleation.

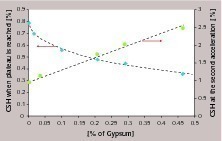

4.4 The beginning and the end of the acceleration plateau

After the first acceleration, the relative acceleration due to the nuclei varies quite linearly with the C-S-H dosage, until reaching a plateau where further additions at first do not further accelerate the hydration. In the case of pure alite systems, this plateau is not observed for alite 2 and occurs above 2 % for alite 1. With some cements, it ends with a second acceleration at high C-S-H dosages. In Figure 6 both characteristics, namely the onset and the end of the plateau, are clearly correlated with the gypsum content. The absence of gypsum in pure alite systems is consistent with the absence of plateau or its occurrence at high dosage in C-S-H seeds. As mentioned above, the seeding can only accelerate the hydration if it is accompanied by a decrease of calcium and/or hydroxide concentration compared to the reference. In other words, the kinetic path has to be pulled towards the lower calcium hydroxide concentrations. However, in cements, the calcium hydroxide concentration is not only determined by the silicate hydration. In this respect, we may assume that gypsum contributes towards buffering the pore solutions in calcium. As long as gypsum is present, it prevents the decrease of the calcium concentration. The length of the plateau is then connected to the gypsum content.

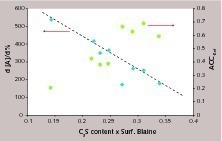

4.5 The acceleration performances

For evident cost reasons, the relative acceleration at low C-S-H dosages is certainly the most interesting for end-users. This varies depending on the cement: in some cements, 1 % of C-S-H seeds will strongly accelerate the hydration, less in other cements. This property can be captured by the relative acceleration per % of C-S-H: dA/d%. The unique acceptable correlation we found is between dA/d% and the available C3S surface area. We approximated this by multiplying the C3S content with the Blaine surface area. Results and the evolution of Accref are reported in Figure 7. Accref follow a very rough tendency: the higher the surface area of C3S, the higher the acceleration. This appears perfectly logical in the absence of additional seeds, since the surface area of C3S probably determines (1) the number of nuclei due to heterogeneous nucleation of C-S-H onto the C3S grains and (2) the kinetic path: the higher the surface area, the higher the dissolution rate, and thus, the nearer the kinetic path to the C3S solubility. When the system is accelerated by seeding, the number of nuclei is fixed and we avoid the precipitation of C-S-H onto the grains. This also means that, the nucleation being controlled, the remaining parameter influencing the acceleration of the hydration, should only be the dissolution of C3S. The increase of the surface area of C3S tends to decrease the relative efficiency of the seeding (Fig. 6). Namely, 1g of seeds will accelerate the C3S hydration less, if this cement either possesses a high surface area or a high C3S content. The acceleration by seeding requires that the kinetic path moves easily towards lower calcium hydroxide concentrations. Then, if the C3S dissolution flow is high, i.e. if the reference kinetic path is near C3S solubility, the ability of seeding to accelerate the hydration will decrease.

5 Conclusions

A new seeding technology, successfully applied in the concrete sector , allows concrete producers to accelerate their production or to replace cement by more cementitious materials. Despite showing a higher robustness compared to classical accelerators, the performances of C-S-H seeds also depend on the cement composition and the cement reactivity. In this study, we have seen that the acceleration provided by seeding is mainly linked to the alkali sulfate content, the gypsum content and the C3S surface area. It has been highlighted that the “dormant period” is not only connected to the nucleation of C-S-H. With a fixed number of nuclei, the effect of the position of the kinetic path is highlighted. All factors regulating the concentration of calcium hydroxide can limit or slow down the hydration, the dissolution of C3S being one of the most important. This conclusion is in contradiction with the usual hypothesis that hydration is purely controlled by the nucleation and growth of C-S-H.