Investigation of hydration mechanisms of alpha and beta hemihydrate

Gypsum-based binders are generally based on the reaction between calcium sulfate hemihydrate (HH) and water to form calcium sulfate dihydrate (DH). Often gypsum can be used as a raw material to obtain hemihydrate. In this study, the obtained alpha hemihydrate consists of large crystals that have more or less lattice defects according to its production process while beta hemihydrate is characterize by a large surface area and fast setting time. The dissolution rate and setting time of α-HH are relatively lower than β-HH, therefore, large dihydrate crystals with fewer branches were formed. The dissolving rate of β-HH and nucleation density of the crated dihydrate was very high due to its high surface area. The gypsum stone which was created from the hydration process out of α-HH is characterized by its higher compressive strength and slower reaction.

1 Introduction

Calcium sulfate hemihydrate [CaCO4 ∙ 0.5H2O(s)] can be found naturally in very dry climate regions in Egypt, Australia, Death valley and Kuwait as bassanite, but in the presence of water or humid atmosphere it can convert to dehydrate [1, 2]. Therefore, the production of hemihydrate industrially has been studied widely through the dehydration process of dihydrate. Based on the dehydration process, the hemihydrate exists in two forms: alpha and beta. Many investigations showed that the symmetry and the water content vary between alpha and beta hemihydrate which might be due to...

1 Introduction

Calcium sulfate hemihydrate [CaCO4 ∙ 0.5H2O(s)] can be found naturally in very dry climate regions in Egypt, Australia, Death valley and Kuwait as bassanite, but in the presence of water or humid atmosphere it can convert to dehydrate [1, 2]. Therefore, the production of hemihydrate industrially has been studied widely through the dehydration process of dihydrate. Based on the dehydration process, the hemihydrate exists in two forms: alpha and beta. Many investigations showed that the symmetry and the water content vary between alpha and beta hemihydrate which might be due to the existence of channels in the lattice structure where the water molecule could be accommodated. According to the large uncertainty about the exact amount of water molecules in hemihydrate, it was claimed that, based on the water vapor pressure during the production of hemihydrate, the water content varies between 0.5-0.8 [3-6]. If the dehydration was performed in dry atmosphere or under vacuum at a tempera-ture range between 110-150°C, the beta form will be generated. This form has special characteristic, such as, irregular crystal shape, small particle size and existence of many surface defects on the hemihydrate crystal surfaces (this kind of defect refers to the direction of cracks along the c-axis ‘cleavage planes’ on the (010) surface). The alpha hemihydrate form is produced either from the autoclave method or hydrothermal method. In the autoclave method, the dihydrate is heated at 110-160° C under high pressure steam or boiled water generating alpha steam autoclave hemihydrate and water autoclave hemihydrate respectively. The heating temperature which is used in the hydrothermal method is relatively lower compared to the autoclave method due to the usage of some inorganic acids and salts. In general, the obtained alpha hemihydrates have acicular, prismatic or rod like crystals with regular shapes and fewer defects compared to the beta form. The purity, strength and stability of alpha hemihydrate are higher than beta hemihydrate while the solubility of beta is relatively higher than alpha [7-10].

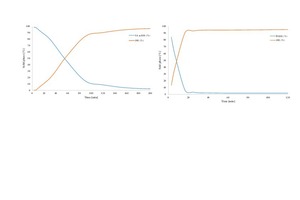

In general, the solubility of calcium sulfate crystal phases has been studied over more than a hundred years by many investigators. It has been established that, dihydrate ‘gypsum’ has very low solubility in pure water at ambient condition compared to the commonly soluble salts such as sodium sulfate. This implies that gypsum has retrograde solubility behavior [13]. The solubility of gypsum mainly depends on temperature, external pressure and water activity [14]. The ‘solubilities’ of hemihydrate and anhydrite have been studied and compared to the solubility of gypsum as shown in Figure 1a. It is clear that, both hemi-hydrate forms and anhydrite have an inverse relation between their solubilities and the temperature [15]. As earlier reported, gypsum [CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O(s)]

can be formed via several processes such as the transformation of hemihydrate or anhydrite upon contact with water and accompanied with the release of heat as shown in Eq. (2) where x and n values depends on the calcium sulfate crystal phase. Another possibility to form gypsum is that the calcium sulfate dihydrate crystalizes through the chemical reaction between Na2SO4(s) and CaCl2(s) as shown in Eq.(2). There are two main theories to explain the mechanism of gypsum formation: the colloid theory and the solubility-crystallization theory [4, 8, 16, 17].

⇥(1)

⇥

⇥⇥(2)

According to the solubility-crystallization theory, the hydration process can be divided into three main stages as follows: (1) dissolving of calcium and sulfate ions in water, (2) crystallization when the ions concentration outweighs the supersaturation point and (3) hardening when the growth process for the formed dihydrate crystals stops and there is no more ions delivery [16, 18]. In this work, two types of calcium sulfate hemihydrates are distinguished as α and β according to the dehydration mechanisms. All raw materials were physically and thermally analyzed in order to ascertain possible variations (particle size distributions, surface morphology, specific surface area, hydration- dehydration mechanisms, setting time and the mechanical properties) existing that originate from different production processes.

2 Results and discussion

The properties of gypsum slurry vary according to the type of hemihydrate. Therefore, a series of experiments were performed as starting point in order to adjust and control the factors that could affect these properties. Table 1 shows the variation in some properties between three types of hemihydrate according to their production processes.

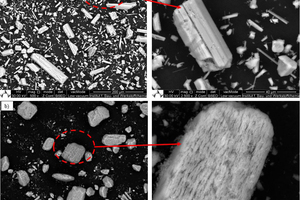

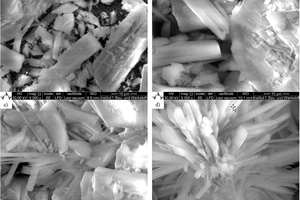

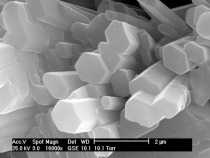

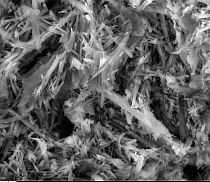

In general, the particle size has an inverse relationship to the surface area, but in the case of β-HH, the number of defects on its single crystal is very large compared to the water and steam autoclave α-HH. These defects which are responsible for the high surface area in β-HH compared to the others are evident in the SEM images shown in Figure 2.

These differences have a large effect on the required amount of water which is needed to achieve a good workability as well as the mechanical properties. The w/s ratio was determined according to a certain slump flow in the range of 82-85 mm.

The crystal morphology varies according to the type and production processes of hemihydrates as shown in Figure 2. The typical column-like structure of α-HH can be clearly seen in the case of unmilled water autoclave α-HH, while the steam autoclave α-HH shows heterogeneous crystal morphology with a large and small column-like structure with fewer defects. As observed from particle size distribution and surface area measurements, β-HH has a large crystal size with a very high surface area. The reason for its high surface area is due to the large number of defects in the single crystal as shown from SEM images in Figure 2c. The disparity between these types of hemihydrate is responsible for their hydration behavior as well as physiochemical properties.

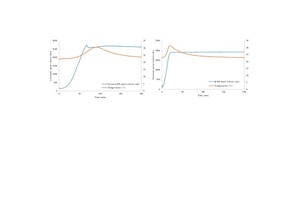

The setting time was determined via the Vicat-cone method as specified by DIN EN 13279-2. In this study, the needle penetration was recorded in mm every 30 seconds and the setting time using this method was defined at the point which the penetration depth reaches 22±2 mm. In order to obtain more information about the setting and hardening of hemihydrate, ultrasonic wave measurement was performed. In Figure 3 (a/b), both temperature and ultrasonic speed velocity against time was recorded. The graphs show an increase in the reaction temperature during the hydration of different types of hemihydrate. The temperature increase started approximately at the same time as of the initial setting which was determined by the Vicat-cone method. The speed velocity of the initial and final setting of each type of hemihydrate was recorded and summarized in Table 2.

Hydration reaction kinetic of different types of hemihydrates was observed using heat flow calorimetry. Figure 3a depicts the temporal changes in the heat development as well as the total heat release during the hydration of steam autoclave (SA) α-HH. As illustrated the hydration mechanism of hemihydrate occurs via several processes.

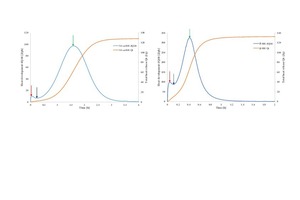

The hydration reaction of SA α-HH can be divided in four steps as shown from the heat development curve in Figure 4a The first peak represents two hydration steps; in the first step, the hemihydrate becomes humidified and a water film will be generated around the particles. This is followed by the solving process of the hemihydrate which should be exothermal because the solubility of hemihydrate has an inverse relation with temperature. This results in the initial increase in the heat development. Through the rapid solving of hemihydrate, the ions concentration increases rapidly until they reach the start supersaturation denoted in the figure with the red arrow. In the next step, after reaching supersaturation the hydration energy decreases up to the point indicated by the blue arrow because of seed crystal formation. During this time period, both processes (solving and seeds formation) takes place. The amount and rate of seeds formation depends significantly on the ion concentration generated from the solving process. It is very important to note that the supersaturation is the driving force behind seeds formation. Moreover, the higher the ion-concentration in the reaction solution, the more seeds are generated.

The second peak of the heat development curve also represents two hydration reaction steps. In the beginning, the reaction energy increases again due to the continuous solving of the hemihydrate without formation of new seeds. In the period which lies between the blue and green arrows, only solving of the remaining hemihydrate in addition to the growing of the created seeds from the previous step, takes place. In the last step which is the retardation period, most of the hemihydrate is consumed and the solving process delivers insufficient ions for the dihydrate crystals to be grown. At this point, when the ions concentration is around the solubility of dihydrate the hydration reaction stops. Figure 4b shows the hydration kinetic throughout the hydration of pure β-HH. The hydration process represents the same hydration processes like SA α-HH. However, the hydration rate in the case of β-HH is much faster than α-HH. Different factors such as the solubility rate in water, particle size and the specific surface area control the hydration rate. As previously shown from Table 1, β-HH has a very large surface area compared to the SA α-HH. Furthermore, the existence of large number of defects on the surface of the β-HH particles depicted in Figure 2b, enhance and increase the solving process. Therefore, β-HH shows a very high heat development at the start of hydration because of its higher solving rate.

According to the summarized information in Table 3, both types of HH (SA α-HH and β-HH), the first hydration step represents only their solving in water until the point where the ion concentration overrides the minimum concentration required for supersaturation to occur. In the second hydration step, both solving and seeds formation takes place. In the final step, the created seeds grow throughout the solving of the unconsumed hemihydrate without any new seed’s formation.

To obtain more information about the hydration mechanisms of different types of hemihydrate, the calcium concentration in addition to the conductivity changes with respect to time were monitored at ambient conditions using the Ca2+-Ion selective electrode (Ca2+-ISE) and the conductivity electrode. As presented in Figure 5, the calcium concentration changes during the hydration of SA α-HH and β-HH was monitored. As previously illustrated from the heat development curves, the hydration steps can be identified and the calcium concentration can be obtained at each step.

A rapid increase in the calcium concentration in the first few minutes represents the dissolving process of calcium sulfate hemihydrate. At this time, the ion concentration overrides their solubility and become oversaturated. The dihydrate crystal seed starts to develop at the minimum concentration of the supersaturation and at this point, the solving rate of hemihydrate is very high compared to the dihydrate seed crystal formation. Therefore, the ion concentration increases until the maximum where the equilibrium between the solving rate and seed formation. Subsequently, when the dihydrate seed crystals formation rate becomes higher than the hemihydrate solving, the concentration starts to decrease. Both processes continue until the concentration drops below the supersaturation range. Afterwards, the created dihydrate seed crystal grows by dragging ions from the solution. It is important to note that in this time period, only growth of the dihydrate takes place without any new seed formation. After a while, once the whole amount of the hemihydrate is consumed, the ion concentration remains constant and become close to the theoretical value of the maximum ion concentration of the dihydrate.

Figure 5a represent the calcium ion changes of β-HH, SA α-HH and the theoretical values of the maximum ion’s concentration of dihydrate as well as the different types of hemihydrate described in Figure 1b. It is clearly shown that the rapid increase in the calcium ion concentration of β-HH than SA α-HH is due to the existence of a large number of defects on the crystal surface of β-HH compared to SA α-HH. The conductivity changes over time were also monitored concurrently with calcium ion changes during the hydration. As shown in Figure 5b, the conductivity behavior has a good correlation with the result of Ca2+-ISE.

From the in-situ X-ray diffraction, the solid phase development can be obtained throughout the hemihydrate-dihydrate transition during the hydration over time. The in-situ X-ray measuring points during the hydration of SA α-HH and β-HH were adjusted according to their heat development curves. The start of measurement depends on the first diffractogram taken by the X-ray machine. Therefore, if the hydration process is very fast, the first transformation cannot be monitored.

Figure 6a describes the solid phase transformation from hemihydrate to dihydrate of SA α-HH. Likewise, Figure 6b describes also the same transformation with reference to β-HH. In both experiments, the X-ray diffraction was analyzed quantitatively using Rietveld refinement to conduct the changes in the solid phase development over the hydration time.

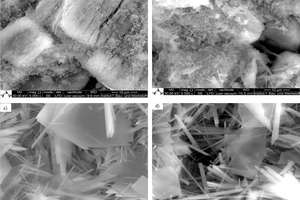

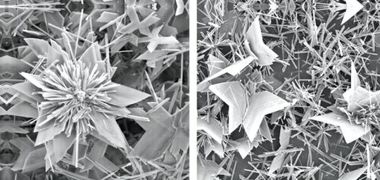

The dissolution rate basically depends on the crystal size and the number of defects on the crystal surface. Therefore, a scanning electron microscope (SEM) was utilized to examine the crystal morphology development during the hydration with high magnification. Figure 7 shows a different hydration process at a different time interval of SA α-HH while Figure 8 shows the same hydration processes in the case of β-HH. In both cases, the hydration processes were clearly identified but in the case of β-HH, the hydration process and crystal morphology development were faster than in SA α-HH.

The samples were prepared outside the SEM in order to obtain dihydrate crystal with single crystal morphology. There was an opportunity to prepare and perform the hydration inside the SEM, but the hydration rate was higher than outside and a dihydrate crystal with different morphologies was created due to the repetition of the condensation-evaporation process on the same sample.

3 Conclusion

It can be concluded that during the formation of calcium sulfate dihydrate from the hydration of pure calcium sulfate hemihydrate, three phenomena are taking place: dissolving of hemihydrate, creation of seeds crystal in the supersaturation solution and seeds growth. The different phenomena and their appearance during the different reaction steps are given in Table 4.

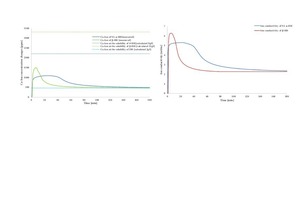

It has been observed that a very high surface area leads to very high heat rate of creating a water film on the surface and fast solving of the first ions. From the different mixtures that have been made to explain the influence of particle size on the seed formation and seed growth mechanisms, it was clearly shown that small particles of hemihydrate affect the seed formation step while the bigger one affects the crystal growth. The smaller the hemihydrate crystals, the faster is their solving speed. Thus, this results in a higher reach of supersaturation of calcium and sulfate ions compared to the solubility of dihydrate. As long as the supersaturation reaches its higher limit rapidly, more branched seed crystals are generated and the hydration rate is accelerated. Larger hemihydrate particles require more time to solve completely and so they can deliver ions for a longer growing process of the dihydrate crystals. The first peak of DCA is mainly influenced by the small hemihydrate crystals. With finer hemihydrate crystals the energy of solvation increases and the first DCA-peak becomes larger as well as the solving rate. The solving of hemihydrate must be exothermic because the solubility of hemihydrate decreases with temperature. So the faster solving of hemihydrate is another reason for a higher first DCA peak if the hemihydrate is finer. The solubility of dihydrate is almost not influenced by the temperature, so the expected solving and crystallization energy is very small. Which means, that the measured energy of hydration is mainly influenced by the solving of hemihydrate, the crystallization energy of dihydrate is only a small factor. Whereas, the growth rate of the generated seed crystals is mainly more dominant since the ions concentration drops below the supersaturation limit. Solving of hemihydrate and growing of dihydrate continues until the solubility concentration. That can be seen by comparing the DCA curves with the calcium concentration measured by calcium sensitive electrode time depending. The results can be supported by optical microscopy. The small hemihydrate crystals mainly influence the dihydrate seed crystal formation, the larger hemihydrates have only a small influence. The larger hemihydrate crystals regulate the growing process, especially the later part, of the dihydrate crystals, because the smaller hemihydrates are already completely solved.

//www.chemie-biologie.uni-siegen.de" target="_blank" >www.chemie-biologie.uni-siegen.de:www.chemie-biologie.uni-siegen.de

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 a) Represents the solubility curves of gypsum, anhydrite,and hemihydrate while b) represent both nucleation and growth processes [11, 12]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/6/0/1/2/7/4/tok_1ff5ec778394ef11ad291e611804165b/w300_h200_x532_y233_Materials_Pritzel_Figure_1-236d0eb0081f17a7.jpeg)