Formation of intermediate phases during hydration of C3S

The described model concepts can be employed as the basis for the development of binding agents possessing a significantly lower energy content and thus generating lower specific carbon dioxide emissions.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

The substitution of Portland cement clinker with latent-hydraulic, inert and pozzolanic materials is an important element in current efforts to reduce the environmental impact. Nevertheless, Portland cement clinker still has an outstanding function in respect of the quantities produced and significance for the strength development. Particularly with regard to the production of cements with rapid strength development, it is not conceivable that the industry could dispense with Portland cement clinker.

Against this background, an understanding of the fundamental processes is necessary in order to assess possible alternatives to Portland cement clinker. In such analyses, tricalcium silicate (Ca3SiO5, C3S) is generally used because a form of this compound that is rich in other oxides (alite) is the main component of Portland cement clinker and is the most important factor for its hydraulic setting.

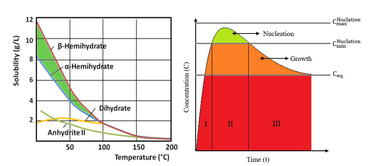

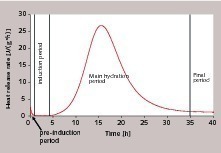

The reaction of C3S with water to form X-ray-amorphous C-S-H phases and calcium hydroxide has been studied for more than 100 years now. It is assumed that the initial substance dissociates in the mixing water or the pore solution to form calcium, silicate and hydroxide ions and that the reaction products precipitate out of the supersaturated solution. This is a continuous dissolution-precipitation process, conversion rates of which vary considerably over the entire course of the process. This can be particularly simply proven by measuring the heat of reaction. As a result of such measurements the process has been divided into different time stages (Fig. 1).

Following an initial release of heat in the “pre-induction period”, there is an apparent period of dormancy that is also referred to as the “induction period”. Generally, the heat release of the first few minutes is attributed to the slaking of free lime, the wetting of the solid material with water, the dissolution of a small quantity of C3S and the formation of the first hydrate phases, although the contributions of these individual reactions are difficult to quantify. The subsequent induction phase of the main hydration is very important from a technological point of view, as it governs the transportation, placing and compaction properties of the produced concrete. Experimental investigations have shown that the length of the induction period can vary greatly. The duration of this process stage is particularly influenced by the properties of the C3S, the reaction temperature and the addition of substances that accelerate or retard the process.

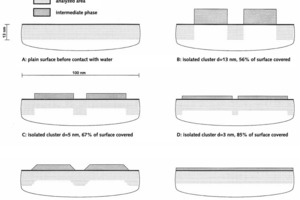

The reasons for the temporal delay of the main hydration due to the occurrence of an induction period are contentious. Early researchers assumed that the formation of a hydrate envelope around the C3S particles is responsible. They also came to the conclusion that the first hydration product is a metastable calcium silicate hydrate, which is transformed in a second step into C-S-H as a stable end product [2, 3]. However, at that time it was not possible to prove the formation of this intermediate product by experiment [4]. Later, various spectroscopic methods were employed in order to provide such proof [5-9]. These analyses revealed that various chemical and physical modifications take place on the surface. A particularly important discovery was that the primary hydrate phases contain uncondensed silicate tetrahedrons (monomers), while the stable C-S-H phases contain dimers and short chains, i.e. condensed silicate compounds. Although these studies succeeded in providing proof of an intermediate compound, they could not show that this covers the entire surface of the C3S. As a result, the formation of a complete envelope (Fig. 2) was not proven and it was also possible to alternatively explain the spectroscopic findings by the presence of clusters of the intermediate phase on the surface of the C3S (Fig. 3). For this reason, alternative mechanisms were proposed for the existence of the induction period. One model postulated the precipitation of nuclei of the stable C-S-H phases as early as the first minutes of the process. All further kinetic steps were attributed to modification of conversion rates of the solution-precipitation reaction due to the composition of the pore solution and the size of the available growth surface [10]. One other hypothesis holds that the reaction speed is dependent on the dissolution speed of the C3S, which is itself influenced by the density of defects in the crystal lattice of the C3S and by the composition of the solution [11].

This article describes experimental investigations aiming to prove the existence of an intermediate compound in the hydration of C3S. The method employed was to concentrate this phase and perform analysis by means of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In a further investigation the surface of the C3S was studied during the hydration process by means of X‑ray photoelectron spectroscopy. This had the objective of ascertaining whether the entire surface of the C3S is really covered by an envelope of the intermediate product. The achieved results form the basis for discussion of the energetic fundamentals of C3S hydration.

2 Proof of an intermediate phase by means of nuclear

resonance spectroscopy [13]

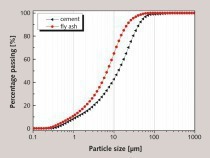

For the investigations, pure C3S was ground in isopropanol to a fineness of approximately 21 m²/g (BET). The ground product contained particles with a diameter of between 50 and 200 nm. The formation of the intermediate phase was investigated after a very short hydration period. Due to the high fineness value, a water to solid ratio of 1.2 was needed for the production of a workable paste. After a hydration period of 5 minutes the reaction was thermally halted. The hydrated sample and the non-hydrated sample were analysed using various methods, including thermal analysis, X-ray diffraction, nuclear resonance spectroscopy and electron microscopy [13]. This article is mainly concerned with the results of the nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). Using 29Si MAS NMR, differences in the chemical environment of the silicon nucleus can be measured. The coordination, the degree of condensation and the mean Si-O distance influence (to various extents) the magnetic fields in the vicinity of the investigated nuclei and thus modify the chemical shifts in the NMR spectrum. The single pulse spectra were acquired at a magnetic field strength of 9.4 T (Varian INOVA-400) and a flip angle of 45° in rotors with a volume of 220 µl. The spectral width was reduced and rotation sidebands were avoided by rotating around the magic angle (MAS).

Figure 4 shows the results of the NMR investigations. The triclinic crystal structure of C3S contains 9 different silicon lattice sites, which normally lead to the detection of 8 NMR peaks, with one peak showing double the intensity of the others. By contrast, the NMR spectrum of the non-hydrated, finely ground C3S (Fig. 4, top) displays very broad resonances. It is impossible to distinguish the individual lattice sites. This is presumably due to the small particle sizes, which cause extreme structural disorder leading to different Si-O bond lengths. After a hydration period of 5 minutes, only slight changes in the single pulse spectrum can be observed (Fig. 4, centre). One particular feature is the absence of any indication for the presence of condensed silicon tetrahedrons (Q1 and Q2), which normally occur in C-S-H. The NMR investigation only verified the presence of non-condensed silicon species (Q0).

The additional recording of 29Si{1H} cross polarization (CP) spectra shows that a large proportion of the silicon tetrahedrons are in close contact to hydrogen nuclei, as direct transfer of the magnetization from 1H to 29Si is possible. This indicates that a high proportion of the silicon is already present in the form of calcium silicate hydrate. However, this phase is not the stable C-S-H with condensed silicon tetrahedrons, but of a phase containing silicon in monomer form (intermediate phase). The degree of hydration can be calculated from the CP spectrum after experimental determination of the CP gain factor under identical conditions in an inversion-recovery experiment. It was calculated with the aid of this value that after a hydration period of only 5 minutes the sample consisted of 79 % intermediate phase and 21 % C3S. In this sample, no stable C-S-H phases as end product of the reaction were detected. Additional analyses of other samples showed that in the further course of hydration a transformation of the intermediate product into C-S-H can be detected, indicating that it is really a metastable compound.

The described experiments proved that if the initial material has a very large surface, a large quantity of intermediate phase can be formed. However, it is not possible to conclude from these experiments whether the entire surface of cement particles of normal fineness is completely covered, or whether the formation of the intermediate phase is responsible for the reduction in reaction speed during the induction period.

3 Investigation of the degree of surface

covering by XPS [14]

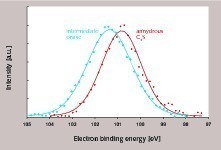

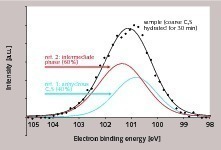

It was already known from other investigations that the binding energy of Si2p electrons in C3S is approximately 100.8 eV [15]. After the transformation to C-S-H phases, Si2p binding energies of between 102.0 and 102.5 eV [16] were measured. These are relatively easy to distinguish from those of C3S. Furthermore, there were indications that the Si2p electrons in the intermediate phase also possess higher binding energies than those in C3S [16]. This experimental method has therefore been verified as both phase sensitive and surface sensitive, which makes it suitable for the investigation of the degree of covering of the C3S surface in the early stage of hydration.

The objective of the described investigations was to determine the proportion of the surface that is covered by the intermediate phase during the induction period. For this purpose, three samples were analysed - two reference samples (non-hydrated C3S, intermediate phase) and one sample from the early stage of the hydration process. To produce the non-hydrated reference, C3S was pressed into tablet form and thermally treated at 1500 °C prior to the analysis. The tablet was broken in the high vacuum of the XPS instrument in order to assure analysis of a fresh, non-hydrated surface. The intermediate phase (reference 2) was produced from nano-C3S analogously to the already described NMR analyses, as those analyses had shown that such samples consist almost completely of intermediate phase. For the actual sample, a C3S with a long induction period was selected (Fig. 1) and the hydration was terminated after 30 minutes by washing with isopropanol.

The XPS analyses were performed in a device (S-Probe) supplied by Surface Science Instruments, equipped with an Al X-ray tube. Different charges in the individual samples were corrected by referring the spectrum to the C1s binding energy of 248.80 eV.

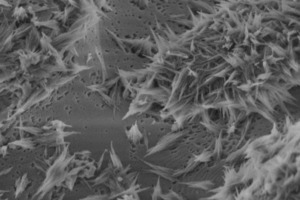

The Si2p binding energies of the two reference samples are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the intermediate phase and the non-hydrated C3S display different Si2p binding energies. However, these partially overlap due to the relatively high half width. Correspondingly, a relatively wide signal is obtained for the actual sample. This signal can be split into the contributions of the two references (non-hydrated C3S, intermediate phase) (Fig. 6). From this, the proportions of C3S and intermediate phase in the analysed volume can be calculated. Three points of the sample were analysed. Mean contents of 56 % intermediate phase and 44 % C3S were determined. No indication of the presence of stable C-S-H phases was detected. In summary, a very high concentration of intermediate phase was detected on the surface of the C3S at a very low degree of hydration (less than1 % by mass). For evaluation of the experimental findings, various geometric situations which would lead to a concentration of 56 % intermediate phase and 44 % C3S in the analysed volume were taken into consideration (Fig. 7). The minimum degree of covering is 56 %, but in this case relatively high islands or clusters of intermediate phase should be visible on the C3S surface (Fig. 7B). Lower layer thicknesses would require a higher degree of covering (Figs. 7C-7E). A homogeneous layer thickness of approx. 2 nm and a complete covering layer would also produce the stated ratio of intermediate phase to C3S in the analysed volume (Fig. 7F). High-resolution scanning electron microscopy showed which of the possible geometric situations of Figure 7 is actually correct. Figure 8 shows a corresponding electron micrograph. It can be seen that the surface of the C3S does not show the humps or surface steps that were assumed in Figures 7B to 7E. The roughness of the surface shown in Figure 8 is less than 2 nm, which permits the assumption that not only a large proportion of the C3S surface is covered, but that there is in fact a complete covering layer of intermediate phase. This confirms earlier models [2, 3, 12] and the schematic representations based on them (Fig. 2).

4 Thermodynamic calculations for the hydration of C3S

5 Derivation of model concepts for C3S hydration

6 Summary

Due to the formation of an intermediate phase on the surface directly after mixing with water, an induction period (dormant period) is observed prior to the main hydration process. This induction period is terminated by the heterogeneous nucleation of the stable end product.

The first reaction already involves more than 90 % of the driving force of the overall reaction. A substantially lower change of energy is available for the second step, which therefore proceeds significantly more slowly.

The described model concepts can serve as the basis for the development of binding agents with a significantly lower energy content and consequently lower specific carbon dioxide emissions. Furthermore, the overall reaction of C3S with water can be accelerated by shifting the shares of energy between the two reactions.

7 Acknowledgements

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![2 Formation of a continuous envelope of reaction products on the surface of the C3S particles in the early phase of hydration [12]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_2942f20087bb7800ec8e2766242cf0a0/w300_h200_x389_y828_101516306_354cd21e50.jpg)

![3 Formation of isolated clusters of the intermediate phase (here designated as C-S-H) on the surface of the C3S particles immediately after contact with water [11]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_e7132e0be385b3c666cac6b9e94719b0/w300_h200_x196_y326_101516318_524fb64b4f.jpg)

![4 Results of 29Si MAS NMR spectroscopy [13]: Top – single pulse spectrum of the non-hydrated nano C3S (vr=6 kHz, 60 s pulse repeat time, 1344 pulses); Center – single pulse spectrum of the nano C3S after a 5 minute hydration period (vr=6 kHz, 60 s pulse repeat time, 1360 pulses); Bottom – 29Si{1H} CP spectrum of the nano C3S after a 5 minute hydration period (vr=3 kHz, 10 s pulse repeat time, CP contact time=1 ms, 2304 pulses)](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_d3b30a5565ec4c173767b48798e80aea/w300_h200_x157_y120_101516315_b804f62988.jpg)

![9 Change in the Gibbs free energy during the hydration of C3S in a single step (left) or in two steps (right). For this calculation, thermophysical data [17, 18] and the following reaction equation were used: C3S + 3.917 H2O ➞ 1.7Ca(OH)2-SiO2-0.917H2O + 1.3 Ca(OH)2](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_27fe079a288eb02a94e328819031db93/w221_h135_x110_y67_101516303_3486673949.jpg)