Superplasticizers in the calcium sulfate system –

plasticizing action and influence on hydration

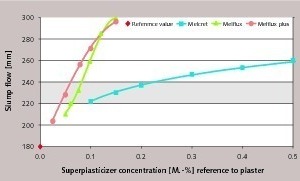

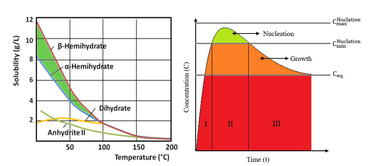

How do superplasticizers influence the hydration of calcium sulfate? Systematic investigations were used to compare the action of polycondensate and polycarboxylate superplasticizers with that of the latest dispersion technology from BASF – a comb polymer with phosphate groups. The addition of the superplasticizers was shown to obstruct not only the nucleation but also the crystal growth.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

The mode of operation of superplasticizers in the calcium sulfate system has been far less researched than in the cement system [2]. The information often relates only to the plasticizing effect or only examines certain parts of the hydration process. The aim of this publication is therefore to examine not only the plasticizing effect but also the action of the three above-mentioned types of superplasticizer on the hydration. The course of hydration was observed in pastes, the nucleation and the crystal growth were examined separately.

2 Current state of the research into the mode

of operation of superplasticizers

In the literature there is very substantial agreement about the basic requirement for the action of superplasticizers, namely the adsorption of the negatively charged side groups of the superplasticizer on the positively charged surfaces of the particles [2, 7, 8]. This involves bonding, based on adsorption, between the anionic superplasticizer and areas with positive charge on the calcium sulfate surface [2, 4, 7]. A clear description of the mode of operation of polycondensates and polycarboxylates in the calcium sulfate system can be found at Peng et al. [2]. The authors show, in the same way as the older literature sources for the cement system, how the adsorption of superplasticizer on the calcium sulfate surface changes the charge distribution of the electric double layer. Transformation of the weakly positive charge into a more strongly negative charge produces an increase in the repulsion forces between the particles and therefore in the dispersion. Polycondensates lie flat on the particle surface and, due to their negative charge, obstruct the agglomeration of the particles through electrical repulsion. In fact, there is also a weak steric hindrance but the dispersion effect is based mainly on electrostatic repulsion. Polycarboxylates have a comb-like structure and are adsorbed with the aid of the negatively charged carboxylate groups on the main chain. The neutral side chains (polyether chains) of the adsorbed superplasticizer produce strong steric hindrance. The dispersing action of the PCE superplasticizers is therefore the result of a combination of steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion. This combination explains the greater effectiveness of PCEs in spite of the lower anionic charge density and lower adsorption rate than polycondensates. Dispersion produced by PCE superplasticizers is comparatively little hindered by advancing hydration, i.e. the loss of flowability with time (slump loss) is reduced. One possible cause of this is the lower adsorption rate of the PCE superplasticizers compared with that of polycondensates. The higher concentration of unadsorbed superplasticizer in the solution means that as the hydration progresses there are more superplasticizer molecules available for adsorption on new calcium sulfate surfaces. Overgrowth of the side chains of the PCE superplasticizer is hypothetically possible. However, this process would take more time than is the case for the polycondensates that lie flat. The consequence would be that the flowability of the mix is maintained for longer [2, 9, 10].

However, alongside the desired effects with respect to workability the superplasticizers also exhibit undesirable secondary effects, such as retardation of the hydration of the binder. From investigations with the cement system it is known that adsorbed superplasticizer obstructs the diffusion of water and ions and therefore adversely affects the nucleation and the precipitation of the reaction products [11]. So far little has been published about observations of this type in the calcium sulfate system. Mention should be made of the work on the interaction of alpha hemihydrate and superplasticizer by Guan et al. [12] that deals with the causes of the retardation action, According to this the adsorption of PCE superplasticizer causes no significant change in the nucleation. However, blocking of some crystal faces was observed that slows down the growth.

The latest dispersion technology from BASF, a comb polymer with phosphate groups, resembles the structural composition of the polycarboxylate ethers. Figure 1 shows that the anionic charge group is formed of phosphate groups rather than carboxylates. The results of Bräu [3] point to increased effectiveness with a significantly reduced retardation action when compared with polycarboxylates.

3 Experimental

The water/solids ratio (l/s) was chosen to suit the test conditions (Tab. 1).

Filtering of the solution in order to produce a virtually homogeneous solution was deliberately abandoned. Experience shows that complete separation of the dissolving and nucleation processes is not possible, i.e. the first nuclei are formed before the hemihydrate has completely dissolved. Filtration of the solution before the onset of nucleation is virtually impossible. Different degrees of obstruction of the dissolving of the hemihydrate depending on the superplasticizer used could not be ruled out so this would also result in differences in the amount of hemihydrate filtered off. The superplasticizer is also known to be adsorbed on the calcium sulfate surface, i.e. superplasticizer molecules would be removed from the suspension with the solids that are filtered off. Filtering the solution at the point when the hemihydrate is fully dissolved is also unfavourable as this represents an intervention into the course of hydration that has already advanced.

The determination of the conductivity was supplemented by mineral phase analysis (X-ray diffraction) using the D 5000 from Siemens/Bruker. The suspension was first filtered quickly (nominal pore size 10–16 µm) and the filter residue was then rinsed several times with isopropanol and dried at 40 °C to stop the reaction.

4 Results and discussions

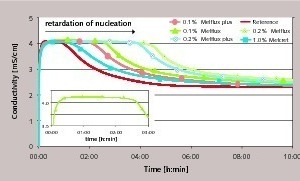

Figure 4 shows the behaviour of conductivity with time for the reference curve and for selected samples containing superplasticizer. A rise in conductivity, which is determined to a great extent by the dissolving of the hemihydrate, can be detected at first in all curves after the mixing of the binder. After passing through a maximum the conductivity of the suspension falls only minimally at first (plateau). The curve then reaches a salient point, after which the conductivity drops rapidly. On the basis of the findings described above the plateau in the curve when the conductivity remains virtually constant can be assigned to the nucleation phase. This means that the term “dormant state” that is often used in this connection describes an equilibrium state. In the plateau region the dissolving of the last hemihydrate and anhydride particles releases ions while the formation of dihydrate nuclei consumes ions. At the same time nuclei below a critical size dissolve and nuclei with radii larger than the critical nuclear radius grow and become dihydrate crystals. Ions are released to the same extent that they become attached. As the reaction continues the formation of dihydrate crystals consumes increasingly more ions. The result is a drop in the conductivity curve. The start of this drop in the curve is defined below as the end of the nucleation phase and the beginning of the crystal growth phase.

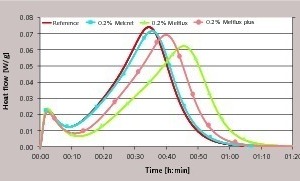

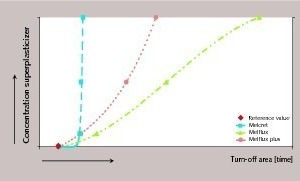

Figure 4 shows very clearly how the use of superplasticizers displaces the salient point in the curve towards later times. This extends the nucleation phase and the start of the crystal growth phase is retarded. The polycondensate exhibits the least retarding action; even a 10-fold increase in concentration leads to only a slightly extended nucleation phase. The greatest retardation is produced by the polycarboxylate. The new type of superplasticizer with phosphate groups occupies a central position. The lowering of the conductivity curve starts more slowly when compared with samples treated with Melcret but earlier in comparison with the use of Melflux. These findings are in agreement with the retarded course of hydration shown in Figure 3 and with the supplementary investigations of the stiffening times that were carried out by the knife cut method. However, it is worth noting that the rest of the reaction is hardly affected. Closer examination even shows a slightly steeper drop in the curve compared with the reference sample. This behaviour is illustrated by conductimetric measurements with a 10-times higher solids content in the suspension (l/s = 20).

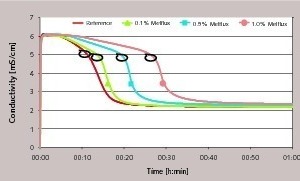

Using the example of the polycarboxylate superplasticizer Figure 5 shows the shape of the conductivity curve in a strongly supersaturated system. It should be borne in mind that with this l/s ratio there is excess hemihydrate present, i.e. hemihydrate is still dissolving when the dihydrate formation starts. The results confirm the interference of the crystallization. This is supported by selected samples that were stopped and then examined by XRD for their phase constitutions. This shows that the addition of superplasticizer extends the period until significant quantities of dihydrate can be detected.

Figure 5 also shows that the addition of superplasticizer not only displaces the moment when the conductivity drops but also reduces its value in the first few minutes. The hydration velocity in the first few minutes decelerates to an increasing extent with increasing superplasticizer concentration. Interference with the nucleation and reduced growth of nuclei or crystals are both possible causes of the depressed initial reaction. This is in agreement with the effects of superplasticizer adsorption already mentioned in the literature.

The superplasticizer can be adsorbed not only on the hemihydrate particles but also on dihydrate nuclei and crystals. A adsorption on the hemihydrate surface does not appear to exert a dominant effect, at least in the first few seconds of the reaction. The maximum conductivity is reached in Figures 4 and 5 with virtually no retardation. The rate of dissolving of the hemihydrate is known to depend on the size and topography of the particles [17, 18]. The rise in ion concentration at the start of the reaction is ensured by the dissolving of the finer hemihydrate particles. Increasingly larger hemihydrate particles are then dissolved as a result of the consumption of the ions; the dissolving takes place preferentially at faults and certain faces. However, at the same time these surface regions also represent preferred adsorption surfaces for superplasticizer molecules. It is therefore possible that the covering of such “reactive centres” by superplasticizer molecules can obstruct the continued dissolving of the hemihydrate. As a result, fewer ions would be released and the reaction would be retarded. Electrostatic interactions of the superplasticizer molecules with unstable clusters could also cause a delay or even obstruction of the growth of the nuclei to form stable nuclei. This would cause ever more nuclei to form, which, with adequate superplasticizer concentration, would also exhibit impaired growth. This type of obstruction of the nuclear growth or extension of the nucleation reaction causes delayed hydration in the first few minutes of the hydration. The same applies to crystals that have already formed where their growth is also obstructed by adsorption of the superplasticizer molecules on the crystal faces with the highest surface energy. The extended nucleation phase and the obstructed growth of the first dihydrate crystals could therefore explain the reduced intensity of hydration. The measurements of the zeta potential in [19] and [20] point to preferred adsorption on dihydrate. The investigations in isopropanol as well as in water showed a higher zeta potential for dihydrate than for hemihydrate.

The marks in Figure 5 indicate the transition to a section of the reaction in which the crystal growth is dominant (turn-off area). It is apparent that with the samples containing superplasticizer there is in fact a time delay in reaching this transition area but the subsequent reaction is slightly accelerated. This is not in contradiction to the retarding action of the superplasticizer. The conditions that occur when the superplasticizer is very largely adsorbed or is possibly partially overgrown can lead to an accelerated reaction. If a fairly large number of nuclei and small crystals are present then correspondingly more growth area is available for further crystal growth. Ions are consumed from the solution to a greater extent. The result is a rapid drop in conductivity, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. This means that the steeper drop in ion concentration is not inevitably caused by increased growth of the individual crystals but can also arise from an increased number of growing crystals.

It is also possible that the particle dispersion has a beneficial effect. It is assumed that the small precipitated dihydrate crystals have a tendency to agglomerate in the reference system, i.e. small accumulations of crystals are formed. Dispersion of the freshly formed dihydrate crystals by the superplasticizer would therefore raise the proportion of freely accessible surface area. More surface area would then be available for deposition of elementary building units, which, with surface-controlled growth, can lead to acceleration. A basic requirement for this is the dominance of the beneficial effect of the greater surface area compared with the reduced reactivity of the surface due to the superplasticizer adsorption.

The regions of transition from the retarded reaction to the crystal growth phase are marked in Figure 5 (using the example of Melflux). Figure 6 is a diagrammatic representation of the transition regions (turn-off areas) in relation to the concentration of the particular superplasticizer. Comparison of the three superplasticizers illustrates the sequence of the retarding action already mentioned. Melcret has the least influence on the course of hydration. Melflux plus causes significant retardation although this is clearly less than when Melflux is used.

Another crucial aspect for nucleation is the complexation of calcium ions on the superplasticizer molecules. This deposition cannot be determined by the methods of measurement used (conductimetry, ICP-OES) and therefore only enters into theoretical considerations. For the present calcium sulfate system it is assumed that the bonding of the cations to the superplasticizer can in fact reduce the probability of nucleation but not the growth of the nuclei or of the crystals. Previous investigations with alkali sulfates and investigations by [21] and [22] in connection with gypsum precipitation during the production of phosphoric acid found high crystal growth rates at Ca2+/SO42- ratios significantly below 1.0. This is attributed to the dependence of the integration rates of the lattice ions on their concentrations in the solution and their integration frequencies. Sulfate ions are known to have significantly larger volumes than calcium ions so sulfate ions exhibit poorer adsorption and integration frequencies. A greater number of sulfate ions in the solution or in the adsorption layer of the dihydrate crystal therefore has a favourable effect on the crystal growth.

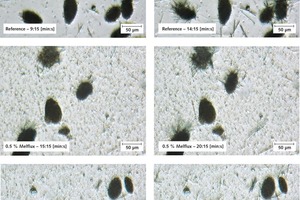

Up to a concentration of 0.1 % none of the superplasticizers caused significant retardation of the observed crystal growth. Differences appeared in the area of the very fine particles at an addition level of 0.2 % relative to the hemihydrate plaster. With the use of Melflux and Melflux plus there were many very fine particles present at the start of the reaction and they dissolved again during the course of the reaction. These could be the first small dihydrate crystals the growth of which was obstructed by the adsorption of superplasticizer and which then dissolved again later as a result of Ostwald ripening. A second possible explanation of these fine particles is the dispersive action of the superplasticizer. Very small particles in the reference sample can agglomerate, i.e. form larger accumulations of particles, without any obstruction but the addition of superplasticizers obstructs the formation of such accumulations of particles. It is therefore possible that the dispersion of the very fine particles leads to an apparently finer particle size distribution.

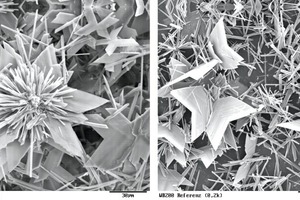

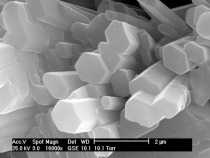

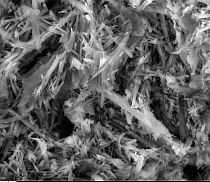

Figure 7 illustrates the growth of the needle-shaped and laminar dihydrate crystals. The large, rounded, particles are hemihydrate particles. The use of 0.2 % Melcret or Melflux plus caused no significant changes to the time until the first dihydrate crystals became visible. Only with the addition of Melflux was this time extended slightly but the crystals that were formed grew only minimally more slowly than with the reference sample. Only above a concentration of 0.5 % Melcret were the crystals visibly slightly delayed but the crystal growth (increase in crystal size) still seemed to be unaffected. At concentrations of 0.5 % Melflux and Melflux plus led both to an extension of the time until the first crystals become visible and to retardation of further crystal growth. Melflux retards the reaction somewhat more strongly than Melflux plus. Figure 7 shows an example of this behaviour in light-optical photomicrographs by comparing the reference sample with 0.5 % Melflux and 0.5 % Melflux plus. The sizes of the crystals present are roughly comparable in the images on the left. The images on the right show the samples five minutes later. It can be seen that the dihydrate crystals in the reference sample have grown significantly more strongly than those in the sample containing the PCE. The Melflux plus superplasticizer caused significantly less retardation. Figure 7 also shows the presence of very small particles in the samples containing superplasticizer. The trials undoubtedly confirm that the crystal growth of the dihydrate crystals is reduced by the presence of superplasticizers. The light-optical photomicrographs support the retarding action sequence already explained: Melcret < Melflux plus < Melflux.

5 Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 Structural composition of the superplasticizers (left: polycondensate, centre: polycarboxylate, right: polymer with phosphate groups) from [3]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_978c63750cdcd38124b90bb24d8c4448/w300_h100_x231_y50_101516192_1f95dac258.jpg)