Progress of hydration and the structural development of hemihydrate plaster

Summary: The phase composition of a hemihydrate binder is crucial for its technological properties such as water demand, workability and rate of hydration. This work deals with the influence of different phase compositions in the binder on the hydration and the resulting solid body properties. This complex process can be reduced to a few characteristic parameters by approximation of this structure formation in a functional relationship.

The hardening of gypsum building materials is based on the crystallization of calcium sulfate dihydrate from a solution that is supersaturated with respect to this phase. The intergrowth and interlocking of the resulting dihydrate crystals is mainly responsible for the formation of a solid body structure and is therefore the source of the strength and stability of gypsum products.

Calcium sulfate occurs in nature as dihydrate, known as gypsum rock, or as water-free anhydrite II. Both phases are used as natural raw materials for the building...

The hardening of gypsum building materials is based on the crystallization of calcium sulfate dihydrate from a solution that is supersaturated with respect to this phase. The intergrowth and interlocking of the resulting dihydrate crystals is mainly responsible for the formation of a solid body structure and is therefore the source of the strength and stability of gypsum products.

Calcium sulfate occurs in nature as dihydrate, known as gypsum rock, or as water-free anhydrite II. Both phases are used as natural raw materials for the building materials industry. Anhydrite II can be used directly but the dihydrate must first be converted into a form that is capable of setting.

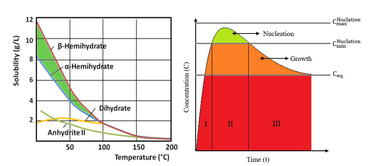

Above a temperature of 40 °C calcium sulfate dihydrate is converted slowly to b-hemihydrate. Technologically meaningful conversion rates are achieved above 180 °C [1, 2]. Hemihydrate plaster is produced by the low-burn process at temperatures of up to 250 °C.

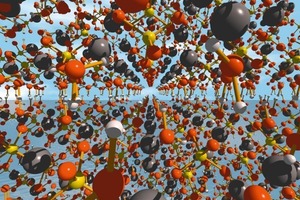

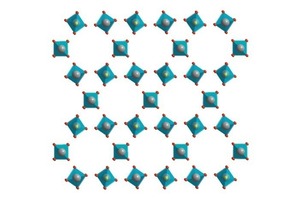

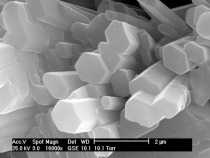

Fairly small particles and the surfaces of larger particles become completely dewatered as a function of the residence time of the material and the temperature in the burning unit. This produces anhydrite III, a very energy-rich and strongly hygroscopic phase. The crystalline structure of anhydrite III is virtually identical to that of the hemihydrate (Fig 1). In both hemihydrate and anhydrite III the calcium ions and the sulfate tetrahedra form alternating chains. In the hemihydrate the crystal water is located in the centre of the hexagonally configured chains. The crystal water is removed during the formation of anhydrite III but the crystalline structure is very largely retained. This is one reason for the great aptitude of anhydrite III for taking up water again. The reverse reaction to form the more stable hemihydrate takes place even at ambient humidity.

Complete dewatering occurs above 200 °C, accompanied by conversion of the structure to anhydrite II. This phase only rehydrates very slowly with water to form dihydrate. As a rule the phase mixture of a hemihydrate plaster exhibits only small proportions of anhydrite II.

On the other hand, the quantity of anhydrite III formed in the binder has practical relevance as it leads to an increase in water demand and promotes particle disintegration. Acceleration of the hydration reaction has been observed where there is only a small proportion of this phase in the binder mix [2]. One possible explanation for this is the rise in temperature that accompanies the anhydrite III conversion and increases the rate of hydration [2]. However, retarded hydration reactions to form dihydrate have been observed when the anhydrite III content is dominant [3]. Furthermore, the marked hygroscopicity of the anhydrite III is technologically significant as it regulates the free moisture in the binder. This increases the storage stability of the product.

This work examines the effects of phase composition on the rate of hydration and the hardening process in the binder. The term “structure formation” is used below for describing the solid body that forms during the hardening.

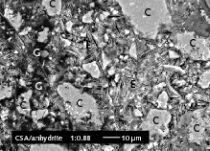

The investigations are based on a natural b hemihydrate plaster formed from Zechstein burnt in a rotary kiln. A virtually complete anhydrite III phase was produced by re-burning this hemihydrate plaster in a drying cabinet for six hours at 160 °C. The anhydrite III contained in the original hemihydrate plaster was carefully converted into hemihydrate for the investigations with an anhydrite III free binder. This conversion reaction was also carried out in a drying cabinet, but for 48 hours at 40 °C. The influence of hemihydrate plaster that has been stored for a long time on the structure-forming properties during the hydration was then examined. The storage was carried out for 28 days at 20 °C and 65 % relative air humidity.

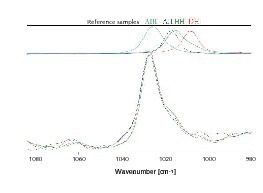

The phase compositions were determined gravimetrically in accordance with internal test instructions [4]. These are given in Table 1. This was supplemented by investigation of the re-burnt hemihydrate plaster by Raman spectroscopy. This provided clear proof of the existence of the required anhydrite III phase (Fig. 2).

The quantity of the starting material required to provide stand-ard consistency as defined in DIN EN 13279-2 gave a water-plaster ratio of 0.71 [5]. The corresponding water-plaster ratio of the re-burnt and stored samples were stoichiometrically corrected to 0.77 and 0.70 respectively (see Table 2).

The measured BET surface areas gave the lowest specific surface area of 4.53 m2/g for the stored hemihydrate plaster and the highest value of 13.70 m2/g for the re-burnt hemihydrate plaster (see Table 2). The specific surface area of the staring material of 7.45 m2/g lay between those of the two hemihydrate plasters that had been subsequently treated.

There are various methods available for quantitative determination of the progress of hydration of the hemihydrate plaster mixes. In principle, the quantity of dihydrate formed can be determined either directly or indirectly by, for example the release of heat or the structure formation.

For direct determination of the development of dihydrate with time, the remaining water was extracted from the gypsum slurry after appropriately specified times. To prevent further hydration in the solid residue this was suspended in acetone and then dried at 40 °C in the drying cabinet. The dihydrate formed was then quantified by Rietveld analysis of the X-ray powder diffraction diagram. The accuracy of the subsequent dihydrate determination was decisively improved by the addition of a known quantity of the fully hydrated sample to the starting material and subsequent calibration. During this calibration it is possible to specify the freely selectable parameters in the Rietveld analysis, such as crystallite size or texture [6].

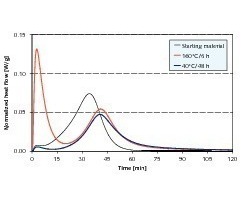

The hydration of CaSO4 · 0.5H2O (HH) to CaSO4 · 2H2O (DH) is an exothermic process. The energy that is released can be quantified in a heat flow calorimeter. By evaluation of the heat energy that has been measured it is possible to draw conclusions about the quantity of dihydrate formed. It must be borne in mind that other effects, such as anhydrite III hydration, heat of wetting and heat of particle disintegration, are superimposed on the quantity of heat measured, especially at the start of the reaction. A heat-conduction calorimeter operating isothermally, in which the sample held at equilibrium can be stirred directly, was used for the investigations. This makes it possible to evaluate the heat flow immediately after the addition of water. The quantity of heat released during the reaction of hemihydrate to dihydrate is 19.3 kJ/mol [2].

The position of the maximum in the rate of heat evolution corresponds to the time of maximum hydration. The wider this peak the slower is the reaction. This means that conclusions about the hydration kinetics of the setting reaction can be drawn from the position and width of the peak.

Finally, the structure formation of the different binders was quantified by oscillating rheometry. This method of investigation is described in detail in [7].

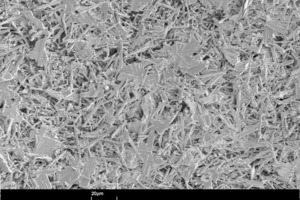

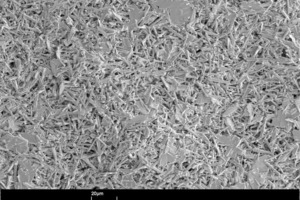

The size, shape and microstructure of the crystals formed were then displayed using scanning electron photomicrographs.

The times measured for the initial setting (is) and final setting (fs) as defined in an internal testing guideline are given in Table 3 [8]. The anhydrite III rich sample and the hemihydrate plaster that had been stored, and was therefore free from anhydrite III, both exhibited initial setting times that were retarded by about four minutes when compared with the starting material. The final setting was retarded by more than five minutes. The setting times of the hemihydrate plaster from long-term storage were also measured. In this case the setting was retarded significantly. The initial setting was displaced by ten minutes while the final stiffening was retarded by 17 minutes. This means that the phase composition of the hemihydrate plaster has a decided influence on the rehydration reactions that take place.

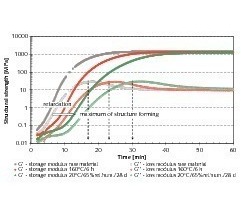

The heat flow, i. e. the amount of heat released per unit time, is shown in Figure 3. Immediately it had been stirred the anhydrite III rich sample produced a marked peak that indicated a strongly exothermic reaction. The heat flow from this reaction, which is attributable to hydration of the anhydrite III, exceeded even the later heat flow of the main hydration to dihydrate.

Both the starting material and the anhydrite III free hemihydrate plaster released thermal energy immediately after the addition of water, although significantly less that the anhydrite III rich sample.

The heat flow stagnated at first after the initial release of heat, but the subsequent main hydration then released thermal energy again.

This intermediate dormant period points to temporary blocking of the hydration reaction from hemihydrate to dihydrate. A basic requirement for the main hydration is an adequate number of stable dihydrate nuclei that are capable of growth. Inhibition of the nuclei-forming process can be regarded as a possible reason for the situation described above. The starting material exhibited the maximum hemihydrate conversion after 34 minutes. Both the anhydrite III rich sample and the anhydrite III free sample only reached this point after 41 minutes.

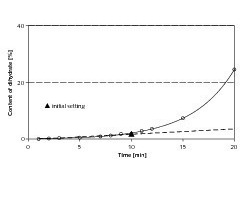

In his investigations Kuzel reported a topotactic reaction of anhydrite III to dihydrate [9]. Its formation directly on the surface could hinder further dissolving of ions, and hence the hydration. For this reason the violent reaction of the anhydrite III rich material at the start of hydration was examined radiographically for possible dihydrate formation. Only a small amount of fresh dihydrate was formed in the first few minutes of hydration (Fig. 4). A disproportionate increase in the quantity of this phase only occurred after a period of more than ten minutes. Retardation of the hydration of the anhydrite III rich binder due to topotactic dihydrate formation on its surface can therefore be ruled out as a cause.

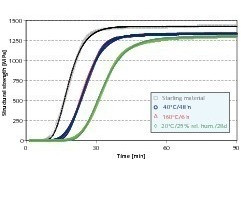

The structure development during the entire period of the setting reaction can be followed with the aid of rheology. By converting the measured values obtained into a suitable analytical form the structure-forming process can be compressed into a few characteristic parameters. This makes it possible to calculate variables such as maximum structure formation or rate of formation.

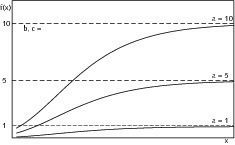

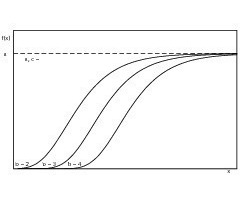

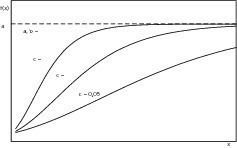

At the start of the hardening process the rate of structure formation increases until a maximum value is reached and then decreases again. This characteristic behaviour pattern is shown in Figure 5. The Gompertz function (1) provides a suitable way of giving an analytical description of this type of sigmoid function. This function is frequently used as an instrument for modelling growth processes [10]. After appropriate modification this function has already been used successfully for analytical description of the setting reaction of hemihydrate plasters [11].

f (x) = a · exp(– exp(b – c · x))(1)

The rate of structure formation is calculated in accordance with (2):

f ’(x) = a · exp(– exp(b – c · x))· c · exp(b – c · x)(2)

The coordinates of the point of inflection are obtained from the zero point of the second derivative and can be calculated by:

xWP = b(3)

c

yWP = a(4)

exp(1)

The abscissa value of the point of inflection (4) shows that this has a constant ratio with the parameter a. The individual effect of the parameter on the shape of the curve that describes the structure-forming process is shown in Figures 6–8. Variable a represents the final value of the structural strength that has been reached while parameters b and c have a major influence on the kinetics of structure formation. Variable b produces a delay in the timing and parameter c varies the rate of structure formation, i.e. the slope of the curve. If the final structure values of two samples differ significantly from one another then its influence on the rate of structure formation should be borne in mind and must be eliminated by appropriate normalization of the final structure values. Analysis of the characteristic structure formation curves can be achieved by evaluation of the approximated variables.

The fitting of the functions to the measured values shown in Figure 5 is carried out by iterative optimization by minimizing the mean-square error. Convergence problems occurred here in the area of the structure formation that was not caused by hydration at the start of the measurements. The structure formations caused by interparticle interactions did not form part of the investigations and for this reason have been ignored.

The parameters that were determined are listed in Table 4. The original hemihydrate plaster mix has the least retardation of hydration, the highest structure formation gradient and the most stable structure at the end of the measurement period.

Both the re-burnt hemihydrate plaster and the anhydrite III free hemihydrate plaster exhibited retarded structure formation. This is made up of a time delay of the start of structure formation and a lower rate of structure formation. The two effects can be considered separately from one another.

The start of structure formation of the re-burnt hemihydrate plaster was retarded 17 % more strongly than that of the starting material. The start of structure formation of the anhydrite III free sample was also delayed by 15 % compared with the original material. It was therefore somewhat less marked. Both the hemihydrate plasters that had been subjected to secondary treatment also had lower structure formation gradients; the re-burnt material had a higher rate of structure formation than the anhydrite III free material. Both lay in the range of about 83–84 % of the rate of structure formation of the original hemihydrate plaster. Superimposition of the two effects resulted in a delay of the time of maximum rate of structure formation of the two materials that had been subjected to secondary treatment of about 38 % when compared with the untreated material.

The hemihydrate plaster from long-term storage exhibited a similar behaviour pattern to that of the two above-mentioned products with a delay of about 23 % compared with the original material. However, with this hemihydrate plaster the rate of structure formation was only about 67 % of the rate of the original material. This lower rate of structure formation led to a delay of the time of maximum structure formation by 82 % compared with the original material. The times of maximum structure formation as well as the associated maximum rates of structure formation of the various hemihydrate plasters are given in Table 5. The times of maximum structure formation correspond very largely with the measured final setting times.

The time of maximum structure formation coincides with the temporary maximum in the development of the loss modulus (Fig. 9). The significance of this temporary maximum has already been described in detail [7] and is attributable to the intergrowth and stressing of the dihydrate crystals formed.

Because of the functional relationships, the structural strength achieved at the time of maximum structure formation (this time corresponds to the point of inflection of the approximated Gompertz function) is firmly linked to the final value of this process and amounts to about 37 % of the maximum value.

However, the structural strength of the hemihydrate plaster at the time under consideration can only be determined by events that have already taken place. This means that about 37 % of the achievable structural strength can be attributed to the free growth and therefore substantially to the crystal form of the dihydrate formed. The more significant proportion of 63 % of the maximum structural strength can be attributed to the interlocking properties of the individual crystals.

When the structure development is compared with the associated heat flow curve it can be seen that the maximum rate of structure formation coincides with the start of the main hydration. If the structure formation were determined solely by the formation and interlocking of the dihydrate then there would have to be a direct relationship between the maximum rate of structure formation and the maximum rate of hydration. This was not found in the investigations that were carried out.

The rate of structure of formation can therefore presumably be attributed to a superimposed effect of the intensified dissolving of the hemihydrate. This means that the dissolving of the hemihydrate affects the structure formation of hardened hemihydrate plaster. More investigations are needed to obtain an accurate description of these relationships.

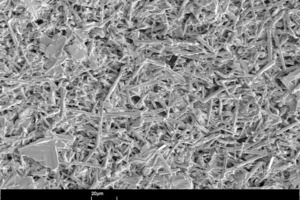

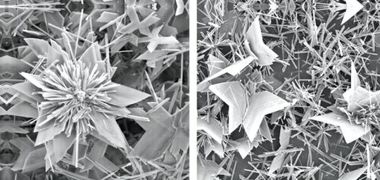

Figure 10 shows scanning electron photomicrographs of the microstructures that have formed in the hemihydrate plasters. The anhydrite III free sample forms large, needle-shaped, crystals. In contrast, the anhydrite III rich sample forms significantly smaller crystals. At the same time there is an increase in the number of plate-like, swallowtail crystals. The number of plate-like, swallowtail crystals is greatest in the original hemihydrate plaster.

This work deals with the influence of different phase compositions of hemihydrate plaster on its rate of hydration and structure formation. The phase composition of the hemihydrate plaster affects its setting reaction with respect to start of hydration, rate of reaction and achievable structural strength. Anhydrite III rich and anhydrite III free hemihydrate plasters both hydrate more slowly than the industrially produced hemihydrate plaster with an anhydrite III content of 16 %. As a rule the attempt is made to describe the setting behaviour of a hemihydrate plaster by determining the progress of hydration. The method described here offers the opportunity of direct determination of the structure development of a hardening hemihydrate plaster. Analytical description of this structure-forming process permits quantification of the hardening process due to hydration. The method of investigation described here makes it possible to analyse these influencing factors independently of one another and in accordance with the significance of their respective effects.

The authors would like to thank Knauf, and particularly the staff of the Research and Development department, for their support. Thanks are also due to the Freiberg Mining Academy Technical University and BASF for carrying out the measurements.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 Crystal structure of a) calcium sulfate hemidydrate [12] and b) anhydrite III (right) [13]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_d7ae785a1819b0066b2493124d897335/w300_h200_x400_y232_101526884_d70343c447.jpg)