Properties of alkali-activated slag cements

This article attempts to quantify the effect of the specific surface area and the particle size distribution of slag on the properties of alkali-activated slag cements. Amongst other things, the normal consistency, the bulk density, the water absorption and the compressive strength have been determined as a function of the setting time.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

Moreover, different types of alternative cements can be obtained by combining GBFS with lime, fly ash, metakaolin, red clay brick waste, microsilica, zeolite etc. One of the stages of cement development with the use of GBFSs (portland slag cement, lime slag cement) was the invention of clinker-free alkali-activated slag (AAS) cements. Numerous studies and long experience have proved their ability to compete with Portland cement, also regarding technical and environmental benefits. AAS cements have a potential availability for “sustainable development” of the cement industry [1].

The fineness of cement was considered as one of the most important characteristics influencing and controlling the properties of cement. The fineness of cement can be characterized by sieving, specific surface area and particle size distribution. With the improvement of the technology for grinding the following factors should be taken into account: the particle size distribution, the shape of particles, the energy input, the abrasive wear and so on [2-11]. Most of the powdered mineral binders are well investigated in terms of the influence of fineness on their properties. At the same time, although most of the mineral binders have common patterns of change in properties with increasing specific surface area and varying the particle size distribution, every kind has its own peculiarities associated with the chemical and mineral composition of the original components, the behaviour of structure formation, the effect on various operational characteristics of the constituents. These investigations are largely carried out with reference to Portland cement and its modifications.

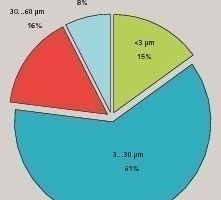

To evaluate the optimal granulometric composition, the different particle size ranges and their optimal content, different studies have been done by various researchers. Matoushek [3] and Ivanov-Gorodov [4] proposed that a proper strength development rate of the cement is obtained with the following size composition: < 5 μm – 15–20 %, 5–20 μm – 40–45 %, 20–40 μm – 20–25 %, > 40 μm – 15–20 %. In 1998, Tsivilis [7, 8] proposed that the percentage of particles with a size of < 3 μm should be lower than 10 %. With a size of 3~30 μm it could be up to 65 % and with a size of > 60 μm and < 1 μm it should be as low as possible.

Butt [13], Venyua [14] and others [15, 16] established that the increase of 1‑day strength is affected by the particles size content < 5 μm, 3–7 days – 5–10 μm, one month and more – 10–20 μm, 90–180 days – 30–40 μm, particles with a size of more than 40 μm contribute to the strength only in a few years. This is due to the fact that generally C3S and C3A are contained in a fraction of less than 20 μm while the larger ones are enriched by C2S and C4AF.

Lingling found [12] that the chemical compositions of narrow particle size fractions show that there are more SiO2, Fe2O3 and MgO in coarse powder, and more SO3 in fine powder. Correspondingly, the content C3S is decreasing gradually with the increasing of particle size, in contrast that of C2S. The content of C3S is as high as 73.5 % and that of C2S is as low as 8.1 % in narrow particle size fraction 0–3 μm. So that the particles with the size of 3–15 μm have a greater contribution to the strength of 3 days, and that of 16–30 μm play a more important role to the strength of 28 days.

Frigione [5] proved that when with the actual grinding technology at cement plants it is possible to minimize the width of granulometric range, the mechanical strength of Portland cements both in Rilem mortar and in concrete can be maximized.

When studying the influence of the GBFS specific surface area on the setting time of AAS cements activated by NaOH, Na2CO3, NaO ∙ 0,9 SiO2 and Na2O ∙ 3,35 SiO2, Andersson and Gram [18] established that the setting time of AAS cement pastes did not show an obvious change when the fineness of the slag was increased from 350 to 530 m2/kg, but decreased noticeably when it was increased from 530 to 670 m2/kg (Blaine) (from 5–20 minutes to 50–140 minutes, depending on the type of alkaline activator).

AAS cements differ from Portland cements in the composition and structure of the initial components, the mechanism of the formation of structure and properties, and therefore, in accordance with the research analysis of the well-known results of the effects of GBFS fineness on the AAS cement’s properties, the optimal and critical fineness depends on the composition and the basicity of the GBFS, the type and concentration of alkaline component and other factors. Glukhovsky noted that when increasing the fineness of fuel slag (residue from the combustion of solid fuels [19]) from 350 to 600 m2/kg (Blaine), the AAS cement’s strength based on it when activated by 15 % of NaOH increases from 55–60 to 75–80 MPa [19]. The limit value of the specific surface for the basic slag for the maximum AAS cement strength is 350 m2/kg Blaine [20].

Shepetov and Brandstater [21, 22] obtained the following results: when increasing the fineness of GBFSs from 200 to 400–500 m2/kg the strength with a sodium silicate alkaline component increases by 1.5–2 times. Pukhalskii and Nosenko [23] showed that increasing the specific surface area of slag with a lime factor (C+M/A+S) 1–1.25 from 250 to 600 m2/kg Blaine when no silicate alkaline component is used makes it possible to increase the AAS cement’s strength from 20 to 60 MPa.

Parameswaran and Chatterjee [24] carried out research on the effect of the specific surface area of GBFSs ranging from 300 to 600 m2/kg Blaine on the AAS cement’s strength activated by NaOH. They found that there is an increase in strength when increasing the specific surface area from 300 to 400 m2/kg, a further increase from 400 to 500 m2/kg Blaine slightly increases the strength and from 500 to 600 m2/kg reduces the strength in the period from 1 to 90 days.

Other studies showed that up to 7 days, the strength of AAS cements increases linearly with increasing specific surface area to 650 m2/kg (Blaine) [25]. The study [26] showed that the critical surface area to reduce the strength varies from 500 to 600 m2/kg (Blaine), depending on the basicity of the slag (550 for “neutral” C+M/A+S = 0,95–1,05, 500 for the “basic” > 1,05 and 600 for the “acid” < 0,95).

The number of known studies on the influence of particle size distribution of ground GBFS on the properties of AAS cements are restricted by studies [27, 28]. Sato [27] and others indicated a decisive influence on the growth of the strength of the AAS cements fraction of slag up to 5 μm. Thus, most of the studies showed the optimum specific surface area for obtaining the proper strength development rate. It is 500–600 m2/kg Blaine. However, the relevant factors relating to this specific surface area particle size distribution and the changes in the granulometric compositions of GBFSs with increasing specific surface area have hardly been studied. The role of the particle size in the property- and structure formation of AAS cements has not been researched yet.

2 Experiments

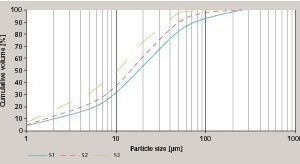

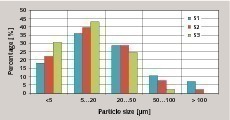

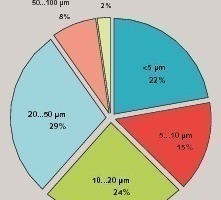

The alkaline activation of the GBFS was carried out using a commercial sodium silicate solution. The silica modulus (Ms = molar SiO2/Na2O ratio) was 1.5, density 1.3 g/sm3, sodium carbonate solution with density of 1.15 g/sm3. The addition of the alkali activator was adjusted to 5 % (by Na2O) of slag in weight. The GBFS was ground in the laboratory planetary mill to a specific surface area of from 300 to 900 m2/kg (Blaine). It were used three samples of GBFS which were obtained by grinding of 100 to 600 sec. The particle size distribution and specific surface area of the powder were tested using a laser particle size analyzer type Fritsch Particle Sizer ANALYSETTE 22 and a Blaine air-permeability apparatus (Figs. 1 and 2).

When increasing a grinding time there is an increase in the content of particles smaller than 20 μm and a reduction in the amount of particles larger than 20 μm (Figs. 1 and 2). The most uneven is an increase in the content of particles smaller than 5 μm, if there is an increase in grinding time from 100 to 300 sec, the content of the fraction is increased by 4.08 % – from 18.13 to 22.21 %, while it is from 300 to 600 by 8.3 % – from 22.21 to 30.5 %.

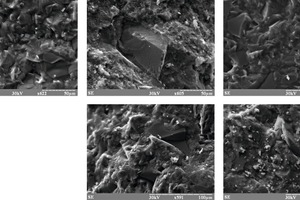

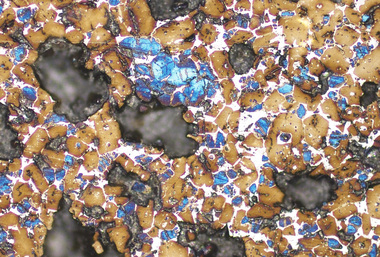

For the slags depending on the fineness Rosin-Rammler equations, the characteristic particle size and uniformity index n were calculated (Table 2). As can be seen, the highest uniformity index n is typical for sample S1. Further reducing of the uniformity index n at a grinding time of more than 300 sec, probably indicates the fine slag particle aggregation. The compressive strength of AAS cements was measured after 1, 3, 7 and 28 days of storage and after steam curing (regime 4+3+6+3 hours). Microscopy study by SEM was performed on a JSM-6460 LV.

3 Results and discussions

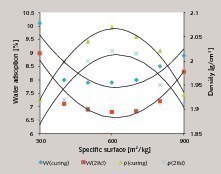

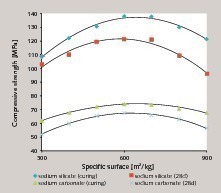

The results of studies of the effect of the specific surface on the bulk density, water adsorption and compressive strength, as well as the behaviour of these three characteristics during the 28 days are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The dependences of the bulk density, water adsorption and compressive strength of AAS cements versus specific surface area of slags regardless of the type of alkaline components and hardening conditions, are characterized by an extreme for S1-based sample (GBFS fineness is 600–700 m2/kg).

In this area AAS cement paste (w/b = 0,28) has the highest rates for bulk density and strength, and the lowest rates for water adsorption. When increasing the fineness from 300 to 600–700 m2/kg, the AAS cement became more “compact” by 7.4–7.8 %. This is accompanied by a decrease of water adsorption by 21.8–24.0 % and a strengthening by 17.4–29.8 %, depending on the type of slag component and hardening conditions. A further increase in fineness from 700 to 900 m2/kg leads to deterioration of the strength and structural characteristics.

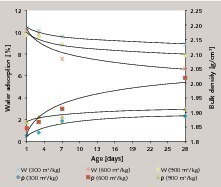

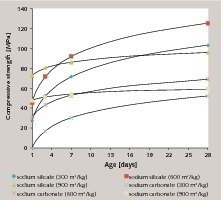

Figure 4 shows the development of bulk density, water adsorption and strength of AAS cements up to 28 days. Table 4 shows the increment in strength at the age of 3 and 7 days relative to the 28-days age, depending on the GBFS fineness. The inherent logarithmical dependences of Portland cement systems describe the development of the strength of AAS cements up to 28 days. The same is observed with the bulk density and water adsorption within 28 days. Analysis of the obtained results revealed differences in the rate and level of the strength formation process of the AAS cement’s samples depending on specific surface area of the slags. The S1- and S2-based samples become “strong” almost at the same rate. The difference in the studied variables in the given time interval is changed slightly.

At the same time, the strength rate for S3-based AAS cement is relatively low, especially after 3 days of hardening. At the age of 1 and 3 days S3-based AAS cement shows the best results, average S2-based AAS cemeent, and the lowest S1-based AAS cement. At the age of 7 days the S2- and S3-based samples have similar strength values. They exceed the respective characteristics of the S1-based AAS cement by 20.6–38.4 % (alkaline component – sodium silicate solution) and by 74.6–92.9 % (alkaline component – sodium carbonate solution). Up to an age of 28 days the strength development rate of the S3-based sample decreases and its strength level approaches the S1-based samples. However, the maximum strength at the age of 28 days has the S2-based sample, which exceeds the characteristic of the S1- and S3-based samples by 21.2–30.4 % (alkaline component – sodium silicate solution) and 16.8–32,3 % (alkaline component – sodium carbonate solution).

The strength level in percent relative to strength at 28-day age (Tab. 4) from S1-based AAS cement to S2-based cement changes slightly – from 50.4 % to 57.3 % at the age of 3 days and from 69.2 % to 73.4 % at the age of 7 days (alkaline component – sodium silicate solution), respectively. The strength level of the S3‑based sample at the age of 3 and 7 days is 83.8 % and 89.8 %, respectively, relative to strength at 28-day age. For the samples activated by sodium carbonate solution the changes in the granulometric composition had a greater influence on the early strength of AAS cements. And if at the age of 3 days the S1-based samples have the strength level 32.8 %, the S2-based samples have 62.7 %, relative to strength at 28-day age.

Thereby, S2-based AAS cement showed the maximum strength, bulk density, minimal water adsorption and a high and persistent strength development rate over time, but has unsatisfactory short setting times and high costs for grinding. A further increase of the fineness impairs the strength and structural characteristics, increases the early strength, but reduces the strength development rate after 7 days, the share of which at this age of 28 days is already 90 %. Hypothetically, S2 GBFS sample has an optimal particle size distribution that conditions the best results for the S2-based AAS cement. S2 GBFS sample has a specific surface area 600 m2/kg, so the obtained results correspond with earlier studies [25,26]. In the S1 GBFS sample a lot of large size particles are present, in the S3 900 m2/kg a lot of fine size particles. Therefore the potential of the S-3 based AAS cement is achieved very quickly (it is possible mostly in the period up to 7 days, in addition probably there is the aggregation of fine GBFS particles and as an effect the high water demand and shortening of the setting times). The hydration process of the S1-based AAS cement is comparatively slow.

It was found from the study that the cement loses strength development potential after 7 days, when increasing the content of the fraction sized < 20 μm from 61 % to 73 % (in particular the size d < 5 μm, which accounts for 8 %) and decreasing the content of fraction sized 20–50 μm from 28.6 to 24.4 %. Consequently, high strength characteristics and proper strength development rate, at least up to 28 days, can be achieved when the content of slag particles < 5 μm is no more than 22 %, total content of particles < 20 μm no more than 61 % and content of particles of 20–50 μm is sufficient and is at least 28.6 %.

As for too short setting times, it is possible to use retarders (for example borax). Secondly in subsequent researches of the optimal particle size distribution of some kinds of blended AAS cements it was found by the authors the that the particle size distribution appropriate to a specific surface ares 600 m2/kg is optimal for blended AAS cements. In addition, the high fineness of the blended cement can be achieved without heightened power inputs on grinding due to a differences in a grindability of the starting materials and dilution of the slag by “supplementary cementitous materials” lengthens the setting times.

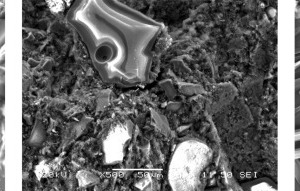

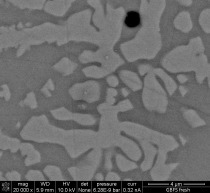

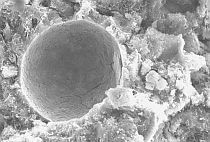

The analysis of the SEM images of the samples (Fig. 5) show the presence of a higher amount of unreacted GBFS particles in the gel of the AAS based on GBFS of 300 and 600 m2/kg than that of 900 m2/kg. At the same time S3-based AAS cement has a lower density than that of S2 based AAS cement. This is caused by the high content of fine GBFS particles that can aggregate and to the higher water demand.

To compare the optimal particle size distributions previously proposed for the Portland cement, the slag particle distributions in fractions of different ranges for the specific surface area of 600 m2/kg are presented (Fig. 6a). A comparative analysis with the previously proposed granulometric compositions shows that dividing into fractions of < 5 μm, 5–10 μm, 10–20 μm, 20–50 μm, > 50 μm, the size composition of slag with the specific surface area of 600 m2/kg (Fig. 6a) is close to the optimal composition proposed by Matoushek [25] and Ivanov-Gorodovoy [17] for Portland cement. Dividing into fractions of < 3 μm, 3–30 μm, 30–60 μm, > 60 μm (Fig. 6b) is close to the optimal one for Portland cement proposed by Tsivilis [28].

4 Conclusions

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.