Numerical investigation on thermomechanical behaviour of refractory masonry with mortar

Refractory masonry is widely used in various industrial furnaces, and its service life determines downtime and production efficiency of the furnaces. To improve the service life of refractory mortar masonry, understanding its thermomechanical behaviour is of first priority. For this reason, 2-D micro models of refractory mortar masonry elements were established for three conditions: undamaged, crack damage, and spalling damage. The influence of different thermal loads on the thermomechanical behaviour of the structures is investigated. The results show that under the condition of constant temperature and no external force, the radial stress on the brick of the undamaged structure is close to zero, and that on the mortar is approximately equal to the product of the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between the refractory brick and mortar, the elastic modulus of the refractory mortar, and the temperature. Under isothermal conditions, only when the damage destroys the symmetry of the masonry, stress concentration occurs near the damage, which is caused by bending stress. However, under thermal shock conditions, as long as there is damage, there will be large stress fluctuations caused by bending stress and axial stress, and the more severe the structural damage, the greater the thermal stress near the damage. More accurate macro model analysis of refractory masonry requires consideration of the interaction between bricks and mortar under thermal conditions.

1 Introduction

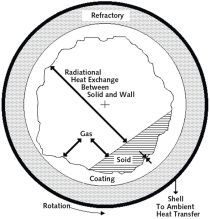

Refractory masonry structures with or without mortar are widely used in various industrial furnaces [1-2]. Different from traditional building masonry, refractory masonry needs to work in a harsh high temperature environment for a long time. Cracking and erosion on the surface of the masonry can be easily caused by thermal shock and high-temperature air scouring [3-5]. The structure will fail with the expansion of cracking and erosion. Therefore, the service life of the lining is often shorter than that of other components, so more downtime is required for maintenance. It can be...

1 Introduction

Refractory masonry structures with or without mortar are widely used in various industrial furnaces [1-2]. Different from traditional building masonry, refractory masonry needs to work in a harsh high temperature environment for a long time. Cracking and erosion on the surface of the masonry can be easily caused by thermal shock and high-temperature air scouring [3-5]. The structure will fail with the expansion of cracking and erosion. Therefore, the service life of the lining is often shorter than that of other components, so more downtime is required for maintenance. It can be said that the service life of the furnace lining determines the length of the repair cycle and the smooth operation of the furnace [6]. In other words, the service life of refractory masonry affects the production efficiency of the furnace.

There are mainly two approaches to prolong the service life of refractory masonry. One is to improve the thermal and mechanical properties of materials by adjusting the chemical composition [7-9], and the other is to optimize the refractory masonry structure. Structural optimization includes changing the size of bricks and joints [10-12], increasing the number of structural layers [13-15], etc. However, the prerequisite for refractory masonry structure optimization is to understand its thermomechanical behaviour. In order to investigate the expansion and compression behaviour of dry joints at high temperatures, the digital image correlation technique was employed, which reveals the process of joint closure and the causes of joint stress [16]. For understanding the strength characteristics of the brick/mortar interface at high temperatures, a new device [17] was developed to measure the tensile, compression and shear properties of refractory masonry at high temperatures. The results show that the masonry structure may be damaged at the interface or in the mortar at high temperature. Furthermore, the cohesion and tensile strength decrease sharply above 900 °C. Although the above-mentioned method is an intuitive experimental test, the simulation can obtain more comprehensive data on temperature, stress, and strain. Therefore, simulation methods have also been widely used in the research of masonry structures [18-20].

For investigating the masonry structure, micro and macro models are two simulation strategies [21-22]. In the micro model, bricks and joints are considered separately. If it is applied to the study of large structures, the model will be very complex. Consequently, in order to study large structures, a representative volume element (RVE) using a micro model was first established to obtain the equivalent material parameters. These parameters are then used to establish a homogeneous model, namely the macro model. For instance, Alain Gasser et al. [23] used an RVE to calculate the equivalent material parameters of refractory masonry with and without mortar, respectively. Then homogeneous models of the bottom lining were established and the results indicate the effects of different masonry designs, joint sizes, and joint types on the thermal stress distribution of the bottom lining. Simona Di Nino et al. [24] calculated the equivalent parameters of mortar masonry walls based on RVE, then established the non-homogeneous model, homogeneous orthotropic model, and homogeneous isotropic model. The results show that the homogeneous model can describe the global behaviour of masonry walls to a satisfactory extent. But the stress on the mortar and joints of the non-homogeneous model is quite different from that of the homogeneous model. That is to say, although the macro model simplifies the calculation, it ignores the different properties of brick and mortar and the interaction between them. It is unable to distinguish the different failure mechanisms of mortar joint cracking and brick cracking. The calculation results are rough and not suitable for detailed analysis of the structure. On the contrary, the micro model can get more accurate calculation results, especially the stress, crack, deformation, failure and other mechanical information of bricks and mortar, which can better describe the local mechanical performance. Incorporating the micro characteristics into the macro structure, may make the results of the macro model more accurate [1, 18, 23, 25].

In the present work, two-dimensional micro models of masonry structures with mortar were established to investigate the micro behaviour of mortar refractory masonry. Combined with theoretical analysis, the influence of joints and damage on thermomechanical behaviour of masonry under different thermal conditions is revealed. At the same time, it provides a theoretical basis for the establishment of a more accurate macro model of refractory masonry with or without damage at high temperatures.

2 Stress analysis

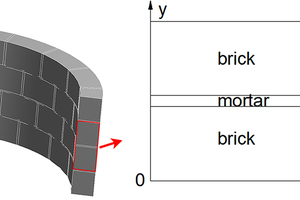

As shown in Figure 1, the representative masonry element is selected to establish a two-dimensional coordinate. The brick-mortar-brick structure can be regarded as a laminated composite material. Previous studies have shown that transverse stress has an important effect on the failure of compo-site laminated structures under thermal conditions [26-27]. Therefore, this paper focuses on the thermal stress in the x-direction (radial direction of the circular furnace) of the representative element.

For masonry elements, axial deformations and stresses as well as bending deformations and stresses in the x-direction under thermal conditions should be investigated [28].

2.1 Axial deformation and stress

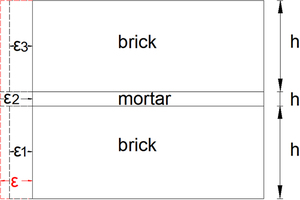

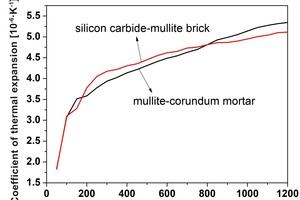

The free thermal strain of bricks and mortar (Figure 2) can be described as:

⇥(1)

Where is the coefficient of thermal expansion, is the temperature change.

Due to the different thermal expansion coefficients of the refractory brick and mortar, their free thermal strain is distinct from each other. But subject to the overall deformation coordination, the overall thermal strain is assumed to be .

The axial thermal stress and internal force generated by the refractory brick and mortar are:

⇥(2)

⇥(3)

Where is the elastic modulus, is the thickness of the material layer.

For the entire structural element, the sum of the

internal forces , therefore:

⇥(4)

Where is the weighted thermal expansion coefficient (the weighted coefficient is the section stiffness of each layer ).

By substituting equation (4) into equation (2), the axial thermal stress of each layer can be expressed as:

⇥(5)

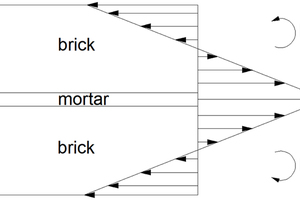

According to the formula above, a schematic diagram of the axial stress on the masonry can be obtained as shown in Figure 3. The axial stress is a piecewise function, which determines the difference in the structural layer stress on both sides of the joint.

2.2 Bending deformation and stress

As shown in Figure 4, is the neutral axis,

K is the deformation curvature, the bending stress at y is:

⇥(6)

The sum of cross-section forces formed by bending stress is 0, and the cross-section bending moment is M, then:

⇥(7)

⇥

⇥(8)

It can be solved that:

⇥(9)

The sum of bending moments formed by axial stress and bending stress is 0, so:

⇥(10)

It can be concluded that:

⇥(11)

By substituting equations (9) and (11) into equation (6), the bending stress can be obtained. It is a continuous function as shown in Figure 5, which determines the change rate of the stress on both sides of the neutral axis.

2.3 Synthesis of stress

The total elastic stress in the x-direction can be obtained by adding the axial stress and bending stress :

⇥(12)

3 Masonry element model

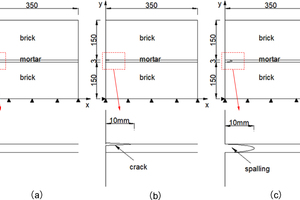

Crack germination, erosion and spalling tend to be the harbingers of furnace lining masonry damage. When cracks or concaves appear, the heating surface at the site of damage gradually expands to the inside of the masonry, which leads to the change of thermal stress. To further contrast and investigate the influence of related factors on stress distribution, two-dimensional numerical models were established in three states: undamaged, crack damage and spalling damage. As shown in Figure 6, the thickness of the brick and mortar is 150 mm and 3 mm, respectively. The crack length and the spalling depth of refractory mortar are both 10 mm. In the simulation, the longitudinal displacements of the bottom edges of the masonry elements are constrained, and the nodes at the lower left corner are fixed.

The furnace operation generally includes stages of heating, production and shutdown for maintenance. The furnace temperature changes slowly during the heating-up and shutdown period, which can be regarded as a quasi-steady state. In the production process, in addition to the thermal shock during charging, the temperature is also relatively stable at other times. So two thermal boundary conditions were applied to the three models respectively:

1. A constant temperature of 1000 °C; 2. The temperature of the left side (damage surface) increases rapidly from 200 °C to 1000 °C within 10 s. Both refractory bricks and mortar are assumed to be isotropic elastic materials. The thermal and mechanical properties of the refractory bricks and mortar are shown in Table 1 and Figure 7.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Under isothermal conditions

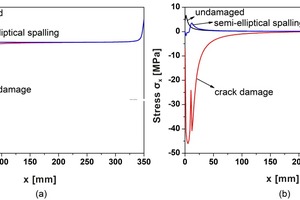

Under isothermal conditions, the stress distribution in the x-direction near the joints of the undamaged structure (in order to avoid the influence of the free edge effect, the middle position x = 175 mm is selected) is shown in Figure 8. It can be found that both sides of the joint are subjected to tensile stress and compressive stress respectively, which may cause its shear failure. This could be one of the main reasons for the cracking of the brick joints. Except for large stress fluctuations near the joints, the stress changes slowly in other places. That is to say, the bending stress and deformation of the undamaged structure under isothermal conditions are very small. It is mainly affected by axial stress and deformation. According to the theoretical analysis in 2.1, the axial stress is mainly determined by the elastic modulus, the thickness of the structural layer, the thermal expansion coefficient and the temperature. Since the thickness of refractory mortar is almost negligible relative to that of brick, the x-direction stress on the brick is close to zero, and that on the mortar is approximately equal to the product of the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between the refractory brick and mortar, the elastic modulus of the refractory mortar, and the temperature. For this article, the theoretical approximation of the x-direction stress on the bricks and mortar are 0 MPa and 9.66 MPa, respectively, which are basically consistent with the simulation results (Figure 8) of 0.1501 MPa and -9.3868 MPa.

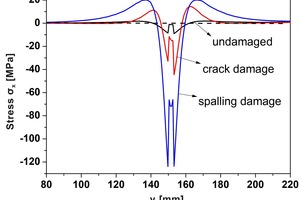

Figure 9 shows the x-direction stress distribution in the middle of the mortar and near the upper joints at a constant temperature of 1000 °C. Compared with the undamaged structure, the stress of the spalling structure does not change much, but there is a large stress fluctuation near the crack. Figure 10 illustrates the x-direction stress near the mortar at x = 30 mm. It is shown that the stress differences on both sides of the joint under the three conditions are almost equal, but the stress near the joint in the crack model changes the fastest. We can infer that the stress concentration near the crack under isothermal conditions is mainly caused by bending stress. However, neither the undamaged model with a symmetrical structure nor the spalling model exhibits stress concentration. It is further inferred that the stress concentration near the crack is due to the bending stress asymmetry caused by the structural asymmetry. It can be concluded that there is no stress concentration around the crack when the crack is in the middle of the mortar.

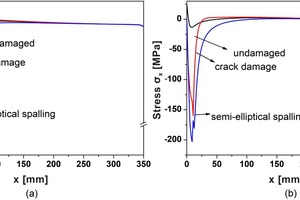

4.2 Under the condition of rapid heating on one side

Figure 11 shows the x-direction stress distribution in the middle of the mortar and near the upper joints at t =10 s when the heating surface temperature rises rapidly from 200 °C to 1000 °C within 10 s. It is obvious that as the damage intensifies, the stress increases. The x-direction stress near the mortar (x = 15 mm) is shown in Figure 12. Under the condition of rapid heating on one side, the stress difference between the two sides of the joints and the stress change rate near the joints of the three models are quite different. Therefore, under thermal shock conditions, the x-direction stress near the damage is determined by both the axial stress and the bending stress. This can partly explain that the damage caused by thermal shock is greater than that under isothermal conditions, namely, the damaged structure has only large bending deformation under isothermal conditions, while there are both axial deformation and bending deformation under thermal shock.

The interaction force between bricks and mortar has an important impact on the high temperature failure of refractory masonry. However, the homogenization model is difficult to highlight the interaction between materials. Therefore, a more accurate high-temperature masonry analysis model needs to incorporate the micro characteristics of the masonry joints into the macro model.

5 Conclusions

Two-dimensional micro finite element models had been established for thermomechanical analysis of masonry elements. The influencing factors of thermal stress distribution under different working conditions were analysed by the models. Then, the effects of cracks and spalling on the thermomechanical behaviour of masonry walls were further studied. The results are summarized as follows:

Under the condition of constant temperature and no external force, the radial stress of bricks in undamaged masonry is close to zero, and that of the mortar is approximately equal to the product of the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between the refractory brick and mortar, the elastic modulus of the refractory mortar, and the temperature.

The stress distribution of damaged masonry under isothermal conditions is mainly affected by bending stress, while the stress distribution under thermal shock is affected by both bending stress and axial stress.

More accurate macro model analysis of refractory masonry requires consideration of the interaction between bricks and mortar under thermal conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 51974211] and the Special Project of Central Government for Local Science and Technology Development of Hubei Province [Grant numbers 2019ZYYD003, 2019ZYYD076].

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.