NOx abatement in the cement industry

The cement industry is getting cleaner, a fact which also applies to NOx emissions. In the last 20 years, primary and secondary NOx abatement technologies have been developed. A combination of these technologies, including selective catalytic and non-catalytic reduction technologies, have become state-of-the-art. This review gives an introduction into what technologies are being used, what emission levels can be achieved and what the installation and operating costs are.

1 Introduction

Cement plants around the world are facing tougher environmental regulations, such as the air emission levels for particulate matter, SO2, NOx, HCl, HF, mercury, TOC, dioxins etc. Nitrogen oxides (generically termed NOx) are highly reactive gases, which are formed when fuel is burned at high temperatures. They contribute to global warming, water quality deterioration and acid rain. Elevated levels of nitrogen dioxide can cause damage to the human respiratory tract and increase a person’s vulnerability to, and the severity of, respiratory infections and asthma. Long-term exposure...

1 Introduction

Cement plants around the world are facing tougher environmental regulations, such as the air emission levels for particulate matter, SO2, NOx, HCl, HF, mercury, TOC, dioxins etc. Nitrogen oxides (generically termed NOx) are highly reactive gases, which are formed when fuel is burned at high temperatures. They contribute to global warming, water quality deterioration and acid rain. Elevated levels of nitrogen dioxide can cause damage to the human respiratory tract and increase a person’s vulnerability to, and the severity of, respiratory infections and asthma. Long-term exposure to high levels of nitrogen dioxide can cause chronic lung disease. Up to 95 % of the NOx formed in cement plants is nitrogen monoxide (NO). In the air this is further oxidised to nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Air quality standards in the EU limit NO2 levels to 40 µg/m3 (average annual exposition), 50 µg/m3 (24h) and 200 µg/m3 (1h) or 105 ppb (1h), respectively.

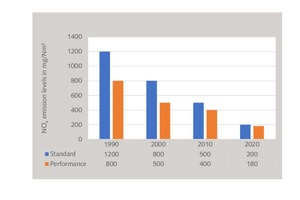

Worldwide, the cement industry emission limits for NOx in the kiln exhaust gas differ widely from country to country, ranging from less than 200 mg/Nm3 (at 10 % O2 for the combustion) for new plants to more than 2000 mg/Nm3 for old plants. Today, in almost all countries there are still different emission limits for old and new plants and type of kiln technology used. Today, the strictest regulations are in the European Union (Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on industrial emissions, IED) and in the USA (NASHEP = National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants by the EPA). Figure 1 shows how NOx emission limits have changed over the years lined up with the technical performances of the plants, derived from Cembureau and the HTC (HeidelbergCement Technology Center). Accordingly, this is an example of how the standards have always closely followed the performances of the plants (BAT = Best Available Technology [1]).

2 NOx formation in cement plants

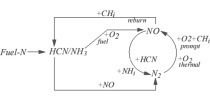

There are two main sources for the production of NOx: a) thermal NOx – part of the nitrogen in the combustion air reacts with oxygen to form nitrogen oxide in the kiln flame b) fuel NOx – nitrogen-containing compounds in the fuel react with oxygen in the combustion air. Furthermore, NOx may also be formed by the oxidisation of NH3, if this is injected for NOx reduction. Thermal NOx, which is the major mechanism of NOx, forms at temperatures above 1050 °C. Due to clinker quality reasons, burning in the kiln takes place under oxidising conditions, so that molecular nitrogen is oxidized to NO mainly in the kiln burning zone, where temperatures are high enough for this reaction. The amount of thermal NOx depends on both the burning zone temperature and the oxygen content. NOx increases with temperature and accordingly, hard-to-burn fuel mixes such as anthracite and petcoke, which require higher temperatures, tend to generate more NOx than fuels such as natural gas or RDF (refused derived fuels), which require lower burning temperatures.

NOx emissions also depend on which kiln process is used. However, worldwide, kilns with precalciner have become the standard and only very few other technologies exist, such as Lepol grates of rotary kilns without precalciner. Accordingly, many different parameters have an influence: burning temperature, air excess factor, flame shape in the kiln, combustion chamber geometry, reactivity and nitrogen content in the fuel, presence of moisture, burner design and residence time for calcining and combustion. According to an investigation by Cembureau in 2007, cement kilns in Europe emitted between 145 mg/Nm3 and 2040 mg/Nm3, with an annual average of about 785 mg/Nm3. For today’s plants, further significant reductions are envisaged using a combination of primary measures and secondary measures (selective NOx reduction).

Figure 2 contains the development in the reduction of NOx emissions by some of the leading cement companies. The specific NOx emissions are given by g NOx/t clinker. Data for mg NOx/Nm3 exhaust gas from the clinker production are not available. Data for g NOx/t cementitious material make no sense from our point of view. The figure shows that there are large differences in the NOx emissions levels, also depending on where the companies operate most of their plants. However, from 2000 to 2018, aside from LafargeHolcim and CRH, there is no clear reduction trend in the NOx emissions, and we think these are still two of the most active companies in the sector. If we look at the producers in other areas of the world, such as in Africa, the Middle East, India and other regions of Asia, the figures are mostly largely above those of the leading companies.

3 NOx abatement solutions

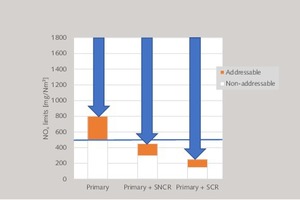

For the reduction of NOx emissions in cement plants a combination of primary and secondary technologies is most prospective. Figure 3 shows the NOx levels that are addressable with the different methods. Primary methods are only able to achieve levels in the range of 500 to 800 mg NOx/Nm3, although it is difficult to achieve min levels below 500 mg NOx/Nm3. Accordingly, secondary methods have to be added for lower abatement requirements. This includes two main solutions. Selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR), which takes place at temperatures between 850°C and 1050°C, and selective catalytic reduction (SCR), which uses catalysts to operate at temperature windows between 250°C and 400°C. Both secondary technologies have been known for many years from the boiler industry and waste incineration. However, the dust load in the cement industry (preheater kilns with 80-100 g/Nm3 and precalciner kilns with up to 180 g/Nm3) is substantially higher than in boiler applications (10-20 g/Nm3).

3.1 Primary methods

There are several primary methods which can avoid the formation of NOx. For environmental and economic reasons, each NOx reduction project should preferably start with the implementation of such methods [1], including:

Optimisation of the fuel mix

Improved firing techniques (low NOx burner, flame cooling, mid kiln firing)

Addition of mineralizers to improve the burnability of the raw meal

Use of low NOx cyclone preheaters

Staged combustion in precalciner kilns

Other kinds of process optimization (energy reduction, etc.)

Today, with low NOx burners and multi-stage combustion (MSC) systems, primary NOx emissions can be reduced to 500 mg NOx/Nm3 [2, 3]. Low NOx burners (Figure 4) have to cope with all kinds of fuels used in the cement industry. They are applied as the main burner at the kiln outlet and for secondary and tertiary combustion at the precalciner or specific combustion chambers. The designs of the low-NOx burners of different suppliers vary in detail, but have in common a multi-channel design where fuel and air are injected through concentric tubes. Up to three air channels are used to provide axial air, radial/swirl air and dispersion air for controlling the flame shape and the burning zone position, and to obtain lower peak temperatures in the combustion zone. The primary air proportion is reduced to about 6-10 % of that required for stoichiometric combustion. Most burners have no moving parts in order to offer a robust and flexible design, with the relative amount of primary air between the swirl and the dispersion channels allowing adjustment between lower NOx (more swirl) and higher solid alternative fuel (more dispersion).

The concept of staged combustion was introduced at cement kilns with precalciners, because such kiln systems allow significant NOx reduction levels due to very low corresponding air ratios and independent settings of the oxidation/reducing levels at the different locations in the system. In comparison, cyclone preheaters without precalciner only allow relatively small reductions of NOx emissions, while substantial preheater modifications are necessary. In a low-NOx precalcining system (Figure 5) the main combustion takes place in the rotary kiln under optimum clinker burning conditions. A second combustion point is located at the kiln inlet in order to produce a reducing atmosphere to reconvert nitrogen oxide generated in the sintering zone to elementary nitrogen. In the precalciner or combustion chamber of the precalciner, a certain amount of tertiary air can be used to generate another reducing burning atmosphere.

3.2 Secondary methods

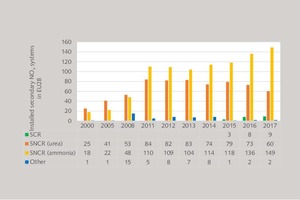

Figure 6 shows the number of secondary NOx abatement systems installed in the EU 28 and also shows the breakdown into different systems. In total, about 220 units have been installed up to 2017, which is about 65 % of the number of kilns in Europe with a capacity of more than 1000 tons per day (t/d). The first SNCR units in the cement industry were installed in 1996/97 in Sweden and Germany. At the beginning, a large number of SNCR systems used urea as the reducing agent. Over the years this has changed to ammonia. The number of SCR systems installed in Europe is still relatively low (just 4 %), but SCR is the trend due to the tougher environmental regulations and limits of 200 mg NOx/m3 for most of the kilns. It can be concluded that in the next few years a number of EU kilns will be converted to the SCR technology. Nevertheless, in international markets the other technologies will also have their market share.

3.2.1 SNCR technology

The SNCR technology involves the injection of liquid ammonia (NH3) or urea (CH4N2O) solutions, leading to the destruction of NOx into nitrogen and water (or water vapour). This reaction can take place spontaneously at around 900°C, or at 300-350°C when using appropriate catalysts. When ammonia is used, the solution is directly injected into the riser duct of the preheater at different locations/levels (Figures 7 and 8). Typically, a reduction in the NOx levels of between 35 % and 65 % can be achieved. Higher reduction efficiencies are generally associated with higher molar ratios. NH3/NOx molar ratios of 0.5-0.9 lead to emission levels <350 – 800 mg/Nm3. With higher molar ratios of 1.0 – 1.2, it is even possible to achieve levels below 250 mg/Nm3, but the so-called ammonia slip becomes more significant and today NH3 levels in the exhaust air are not permitted to exceed 30 mg/Nm3. From an environmental perspective it is reasonable not to apply the SNCR method for maximum NOx abatement, but to achieve a significant reduction with low NH3 escape.

SNCR and high efficiency SNCR systems are applicable at all cement rotary kilns with or without preheater. The installation is relatively easy. Only little additional equipment is required, such as a tank installation with unloading station for the reducing agent (Figure 9), a pressure pump and control skid for pumping the solution, the piping to the riser duct, the nozzle system for spraying and distributing the solution as well as a control system for the ammonia, to determine the optimum ammonia injection rate for maximum NOx reduction and minimum ammonia slip. Depending on the local regulations for the storage of ammonia water, the construction of the storage accounts for a large proportion of the investment costs. If urea solutions are used as reducing agent, the storage facility is not so sophisticated and is safer, because no explosion protection is required, but it does need a water treatment system and heat-traced storage and piping.

3.2.2 SCR systems

The catalytic SCR process, which is state-of-the-art in the power sector, was not used in the cement sector until 20 years ago. In 2000 a first full scale demonstration unit was installed at a cement plant in Germany. Figure 10 shows the principle of the process. The raw gas is directed through the SCR reactor, which is filled with catalyst layers of either titanium-, vanadium- or tungsten oxides. Typically, an ammonia solution of 25 % concentration is used as reducing agent. This allows an essentially stoichiometric reaction to be achieved between NH3 and NOx, so that the side effect of NH3 emissions is small, even at very high NOx reduction rates. Depending on plant circumstances, NOx abatement levels of 80 % and even more are possible. Results of one of the first SCR plants in Monselice, Italy, which went into operation in 2006, are shown in Figure 11. The performance of the SCR system significantly exceeds that of SNCR systems, especially at lower molar ratios [2].

SCR installations can be designed in three different configurations [4]. Each one has its advantages and disadvantages. In the high-dust (HD) version, the SCR reactor (Figures 12 and 13) is directly placed behind the preheater. This leads to no interference with the main process, is the easiest option for retrofits and is the lowest investment cost option, but needs frequent cleaning of the catalyst and has the lowest availability. In the semi-dust (SD) version, an ESP is placed after the preheater and before the SCR. The advantages are easier cleaning of the catalyst, and higher SCR availability, but this configuration causes higher installation costs and additional energy requirement of the ESP. In the low-dust or tail-end (TE) version the SCR is placed behind the ESP, such as in conventional ESP flow-sheets. Accordingly, no dust cleaning of the SCR is required and the lifetime of the catalyst is the longest. But this is the most costly version, because under normal conditions reheating of the flue gas and heat exchangers are required in order to enter the temperature window for the NOx reduction.

Because of the relatively high complexity of SCR systems, there are now technologies on the market which combine SCR technology with other environmental protection technologies, such as the reduction of VOCs (volatile organic compounds) and CO (carbon oxide). One such integrated exhaust gas cleaning system is called “deconox”. The deconox process combines thermal oxidation (RTO) with a low dust or TE SCR. With this system, nitrogen oxides and organic carbon compounds can be reduced at the same time. In first installations in Austria and Germany (Figure 14) outstanding results were achieved. NOx was reduced by up to 90 %, while VOC and CO were reduced by almost 100 %. The heat produced in the afterburning process covers part of the thermal energy requirement (autothermal operation) for the NOx reduction. As a result, the energy requirement for the deconox process is considerably lower than that of a conventional TE SCR.

4 Costs of NOx abatement

The investment costs for NOx abatement technologies depend on where the installation has to be located, but mainly on the kiln size, age and initial NOx emission level before any modifications are made. Detailed cost examples are given in [1], although for most of the individual measures relatively large costs spans were stated. Furthermore, it has to be noted that due to a larger competition among plant suppliers in the sector and to scale effects, there has been a steady cost decline in the last few years. However, when comparing costs, it is very essential to indicate what is included in the costs and what is not included.

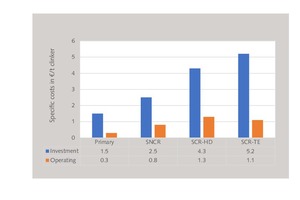

Figure 15 gives a cost comparison of the different NOx abatement technologies. The data is from OneStone Research and indicates the costs for four different technologies, based on a cement kiln with a clinker capacity of 3000 t/d or 1 million tons per year (Mt/a). The costs are related to a reduction of the NOx level from 1800 to 600 mg/Nm3 for primary reduction, from 700 to 350 mg/Nm3 for the SNCR technology and from 700 to 200 mg for the two SCR technologies. The investment costs only cover the equipment costs for the specific technologies, e.g. tank and agent receiving system, pumping, distribution and spraying for SNCR and SCR plus reactor and catalyst filling for the SCR systems. Not included in the costs are steel construction, foundations, erection, commissioning and similar costs, as they are very dependent on local purchasing conditions. The additional operating costs include energy costs and costs for the reducing agent and catalyser but do not include maintenance costs, although the cost for the agent also differs widely.

The primary methods involve the lowest investment costs, which mainly include the costs for the low-NOx burner and the MSC system and subsystems. These costs of about 1.5 €/t clinker (or 1.5 million € for a 1 Mt/a clinker production) also have to be taken into account if any secondary solution is to be added. The investment costs for SNCR systems amount to 2.5 €/t, of which the tank storage facility and reducing agent distribution systems account for a high proportion. SCR systems with the TE version have the highest investment costs of about 5.2 €/t, which is still less than 3.5 % of the investment costs for the complete cement plant. In terms of operating costs in €/t, the SCR HD version produces the highest costs, due to the frequent cleaning and exchange of the catalysts. However, the operating costs for the SNCR version are also relatively high, due to the high molar ratio of these plants and the NH3 slip.

5 Market outlook

NOx abatement has become state-of-the-art in the cement industry. Although there are large differences in the emission limits from region to region and country to country, cement producers and new investors will face tougher regulations in all areas of the world. Especially new clinker production plants will need secondary abatement technologies, while older operating plants will still be able to just invest in primary methods to achieve NOx limits below 600 – 700 mg/Nm3. If the limits are at 400 mg/Nm3, then the SNCR method is the best option from an investment and operating cost view. The method is available for retrofits, too. If limits of 200 mg/Nm3 have to be achieved, only the SCR method is appropriate. The SCR-HD version is probably the best option for retrofits, while the TE version is more appropriate for new plants, especially, when integrated exhaust gas cleaning technologies are required.

//www.on" target="_blank" >www.on:www.onestone.consulting

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![7 Typical arrangement of an SCNR system [4]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/5/0/4/2/0/2/tok_564b8cc68e6cd8f1d6af8d572cf3f105/w300_h200_x600_y359_Fig7_Matz_AAPCA_L-572f6df12a2f2ca5.jpeg)

![10 Typical arrangement for an SCR system [2]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/5/0/4/2/0/2/tok_8c94ba8ae0e256db1b518e0791430fa3/w300_h200_x579_y403_Fig10L_SCR_system_tkIS-7452e0242a90c0c3.jpeg)

![11 Performance results of an SCR system [2]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/5/0/4/2/0/2/tok_4bfcfb05dcbfa131e4278b2453aa50d6/w300_h200_x445_y268_Fig11L_SCR_performance_tkIS-8723f31034ad8862.jpeg)