Experimental study on the influence

of water/cement ratio and polypropylene

fiber on the mechanical properties of

nano-silica concretes

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of polypropylene fiber and water/cement ratio on the compressive, tensile, flexural and abrasion strength, porosity and hydraulic conductivity of nano-silica concrete. Other properties of all specimens displayed extensive mutual similarity. The experimental findings show that, with decreasing water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3, all mechanical properties of the concrete improved, while any further decrease in the water/cement ratio caused deterioration of the flow properties and performance of the concrete, i.e., a reverse effect on its mechanical properties. The highest compressive strength was achieved by introducing 0.1% fiber together with nano-silica. The highest tensile and flexural strength levels, in turn, were obtained for 0.25% fiber, while 0.15% fiber yielded the highest and lowest coefficients of hydraulic conductivity and porosity, respectively, in the concrete samples.

1 Introduction

Due to the fundamental role they play in the economic system of any country, concrete dams are considered as strategic structures. Consequently, the concrete used for building such important structures should display adequate durability and performance. Polypropylene fiber and the water/cement ratio are major factors governing the durability and workability of concrete. It therefore appears advisable to investigate those parameters more closely.

[1] analyzed the effects of various types and volumes of fiber on the characteristics of self-compacting concrete. The same authors also...

1 Introduction

Due to the fundamental role they play in the economic system of any country, concrete dams are considered as strategic structures. Consequently, the concrete used for building such important structures should display adequate durability and performance. Polypropylene fiber and the water/cement ratio are major factors governing the durability and workability of concrete. It therefore appears advisable to investigate those parameters more closely.

[1] analyzed the effects of various types and volumes of fiber on the characteristics of self-compacting concrete. The same authors also studied the effects of steel fiber, basalt and polypropylene on the performance and potentials of fresh concrete with different geometric parameters. [2] studied the impacts of steel and polypropylene fiber on the mechanical properties and microstructure of concrete. They concluded that increasing the volume of polypropylene fiber decreases the material’s fracture energy. The results demonstrated that adding a definite amount of fiber to a concrete mix will significantly alter its microstructure. The smallest microcrack was observed in the transition zone between the concrete paste and aggregates of steel-fibered concrete. [3] probed the effects of various combinations of polypropylene and steel fiber on the failure behavior of reinforced concrete. Specimens containing only polypropylene fiber proved extremely resistant to disintegration, and their ductility was found to be higher in regions displaying small cracks. [4] analyzed the properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete containing polypropylene and steel fiber. They found that the rational use of fiber can improve the mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete specimens. [5] studied the abrasion resistance of classic and normal concrete containing two types of polypropylene fiber. The water/cement ratio was varied between 0.5 and 0.7. According to the findings, the structural abrasion resistance was inversely proportional to the water/cement ratio. Concretes displaying high compressive and flexural strength also have high abrasion resistance. Reinforced micro-concretes were found to have higher abrasion resistance in comparison with that of benchmark concrete. [6] explored the effects of polypropylene fiber on the mechanical and physical properties, compressive and flexural strength, water absorption and shrinkage of mortars containing nano-silica. The findings verified that nano-silica improves the mechanical properties and water absorption (of the mix), and that the microstructural properties of cement mortar can be effectively improved via the composition of mortar and nano-silica. The performance of polypropylene fiber improves in the presence of nano-silica, hence also improving the properties of the cement mortar. [7] conducted a comparison test on the behavior of reinforced concrete slabs containing steel and/or polypropylene fiber. The results showed that 1vol.% steel fiber has the best effect on slab ductility. Moreover, polypropylene fiber expands the energy absorption capacity of concrete slabs more than does steel fiber. [8] investigated the reinforcement of concrete with three types of fiber: glass, polypropylene and polyester. The results disclosed that the inclusion of any type of fiber reduces the workability of the concrete. Likewise, fiber-reinforced concrete was shown to fracture with considerably more need for caution than would be expected for normal concrete. [9] probed the effects of fly ash and various types of local fiber (such as coconut), steel and polypropylene fiber on concrete properties. They concluded that the mechanical and structural properties of normal concrete can be improved by substituting cement with fly ash and locally available fiber.

[10] investigated the use of waste textile fiber for concrete reinforcement and general building purposes. The aim here was to shed light on the effects on normal mortar of nano-silica with various amounts of polypropylene fiber in the aforementioned waste material. The compressive and flexural strength levels were established. The results verified that nano-silica amplifies the ability of polypropylene fiber to improve the mechanical properties of concrete. [11] explored the effects of cement type, cement content and water/cement ratio on the resistance of concrete to sea water. The findings revealed that mixtures of (blast furnace) slag and cement have superior mechanical properties and are considerably more resistant to chloride penetration by sea water than are Portland cement mixes. [12] evaluated the effects of polypropylene fiber on the compressive and tensile strength of concrete. In this case, polypropylene fiber was shown to improve both of those characteristics. In the aforementioned papers, little attention was paid to the effects of water/cement ratio and polypropylene fiber on the mechanical properties of concrete. Thus, the aims of the present research include consideration of the effects of water/cement ratio and polypropylene fiber on six mechanical characteristics of concrete (including compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, abrasion resistance, hydraulic conductivity and porosity), as well as studying the behavior of concrete across a broader range.

2 Experimental procedure

2.1 Materials and mixture proportions

The following conditions were postulated in preparing samples of nano-silica concrete mixes:

The characteristic design strength was assumed as 50 MPa

The water/cement ratio was varied between 0.3 and 0.5

The employed cement was type-I Portland

The optimized nano-silica content replaced 4 wt.% of the cement

The employed fiber was polypropylene, 12 mm long by 0.1 mm thick

The slump-test specimens ranged from 60 to 120 mm in acc. with ASTM C143-78 [13]

Fiber was introduced in proportions of 0, 0.1, 0.15 and 0.25 vol.%

Gravel and sand were employed as ballast aggregate

The maximum size (diameter) of aggregate was 12 mm

Melcret TB 101 served as superplasticizer

Chemical analysis of the nano-silica and type-I Portland cement produced the results shown in Table 1, and the corresponding properties of the polypropylene fiber are listed in Table 2. Polypropylene fiber is resistant to chemicals such as acids, alkalis and chlorides and displays low electrical and thermal conductivity. It is also hydrophobic, showing near-zero water absorption. The polypropylene polymer fiber used in the preparation of test samples is shown in Figure 1.

The grading of aggregates (gravel and sand) and the design of nano-silica concrete containing polypropylene fiber were implemented pursuant to the standards ASTM C136 [14] and ACI-211, respectively. The latter was performed according to the weighting method, the results of which are listed in Table 3.

2.2 Test methods

The subject research involved the following tests performed on concrete specimens:

Compressive strength testing of 15 x 15 x 15 cm3 cubic specimens at 7, 28 and 90 days by means of special test jacks in accordance with ASTM C39 [15]. Figure 2 illustrates the compressive strength test setup for concrete specimens

Tensile strength testing of 15 x 30 cm cylindrical specimens at 28 days by the indirect splitting method (Brazilian test) in accordance with ASTM C496 [16]. The following equation was used for tensile strength calculation:

(1)

Where P is the applied load at the moment of fracture, L and D are the length and diameter, respectively, of the cylinder. Figure 3 shows the tensile strength test apparatus for concrete specimens

Flexural strength testing of 10 x 10 x 50 cm3 prismatic beam specimens at 28 days in accordance with ASTM C1018 [17]. The following equation was used for flexural strength calculation:

(2)

Where P, L, b and d are the applied load at the moment of fracture, the length of specimen, the width of section, and the height of section, respectively. Figure 4 depicts the flexural strength test apparatus for concrete specimens.

Abrasion resistance testing of 15 x 15 x 15 cm3 cubic specimens at 28 days by the water sand-blasting method in accordance with ASTM C480 [18]. The following equation was used for calculating the abrasion depth:

(3)

Where he is the abrasion depth, V the voids volume and A the area of the triturated surface. Figure 5 is a schematic representation of the abrasion resistance test apparatus for concrete specimens.

Hydraulic conductivity testing of 15 x 30 cm cylindrical specimens at 28 days by the penetration depth method in accordance with ASTM C1920-5 [19]. The following equations were used for calculating the hydraulic conductivity and porosity of concrete specimens:

(4)

Where Kp is the coefficient of concrete permeability [m/s], hp the permeability depth [m], T the water permeability time [sec], h the pressure-induced height [m], and V the porosity of the concrete, as derived from the following porosity equation:

(5)

Where w/c is the water/cement ratio; α the degree of cement hydration, w the specific weight of the concrete water [kg/m3] and g the specific weight of the cement [g/cm3]. Figure 6 illustrates the test apparatus for determining the depth of water penetration and the coefficient of hydraulic conductivity of concrete specimens.

3 Experimental investigation and results

3.1 Compressive strength

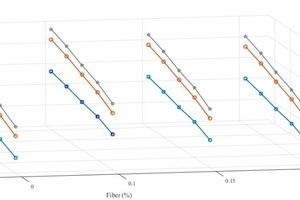

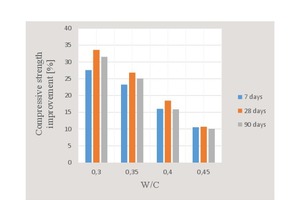

The compressive strength variation curve of fiber-containing specimens at 7, 28 and 90 days as functions of water/cement ratio and fiber content (percentage) are shown in Figure 7 for mixes of various design. The greatest compressive strength of all specimens (containing 0, 0.1, 0.15 or 0.25 vol. % polypropylene fiber) was achieved by specimens with a 0.3 water/cement ratio, while the lowest compressive strength was displayed by those with a water/cement ratio of 0.5. Figure 8 illustrates the percentage of compressive strength improvement in non-fibrous specimens for water/cement ratios below 0.5 at 7, 28 and 90 days. Accordingly, reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 improved the compressive strength of specimens by 27.54 %, 33.55 % and 31.51 %, respectively.

As illustrated in Figure 9, adding 0.1 % fiber (PP) to mixtures with a water/cement ratio of 0.3 improved the compressive strength of the specimens at 7, 28 and 90 days by 21.57 %, 15.1 % and 13.98 %, respectively. Similarly, adding 0.15 % PP to the mix improved the compressive strength of the specimens at 7, 28 and 90 days by approximately 13.4 %, 8.98% and 8.31 %, respectively. Finally, the addition 0.25 % fiber improved the specimens’ compressive strength at 7, 28 and 90 days by some 8.78 %, 5.53 % and 5.09 %, respectively.

As we see, adding 0.1 % fiber, improved the compressive strength at all three ages, while the use of more than 0.1 % fiber detracted from that gain due to unsuitable distribution of the fiber content. Maintaining the employed percentage of superplasticizer at a constant level while increasing the fiber content reduces concrete slump while also decreasing the specimen’s compressive strength. Adding more fiber increases the porosity of the concrete specimens.

3.2. Tensile strength

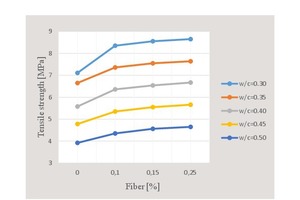

Figure 10 illustrates how adding 0.1% fiber exerts a positive effect on tensile strength. Higher proportions of fiber increase the tensile strength accordingly, but the slope of the curve gradually flattens.

Non-fibrous specimens are subject to a kind of disintegration on fracture, but adding fiber thoroughly resolves that problem.

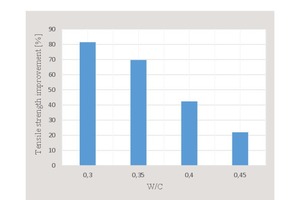

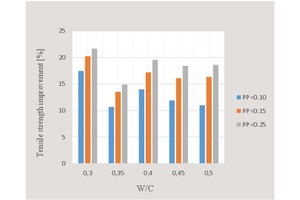

Figure 11 shows that reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 improved the tensile strength of non-fibrous specimens by 81.38 %.

In Figure 12, the tensile strength of the specimens is seen to improve by 17.44 %, 20.25 % and 21.66 %, respectively, on addition of 0.1 %, 0.15 % and 0.25 % fiber to a mix with a water/cement ratio of 0.3.

One shortcoming of plain concrete is that it has low tensile strength. Lacing it with fiber increases both its tensile strength and its ductility thanks to the higher tensile strength of the fiber.

While using up to 0.25 % fiber improves the tensile strength of the specimens, that tensile strength presumably will decrease if more than 0.25 % fiber is added. This behavior is attributable to unsuitable distribution of the fiber, as to be observed on the visible surface of the specimens. The line of fracture passes approximately through the regions displaying low fiber density. In other words, the use of more than 0.25 % fiber subjects the specimens to the balling phenomenon, because excessive fiber content induces blockage within the concrete, hence practically eradicating the positive effects of fiber.

3.3 Flexural strength

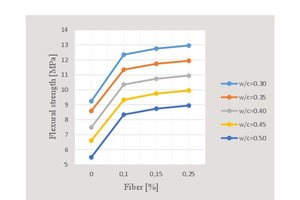

Figure 13 establishes a positive effect on flexural strength through the addition of 0.1 % fiber. Higher proportions of fiber further increased the flexural strength of the specimens, but at a slower pace. Specimens containing fiber display two principal status relationships between cracks and fiber: vertical and horizontal.

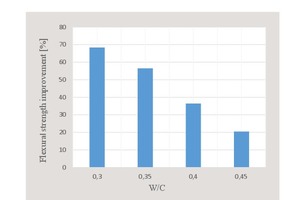

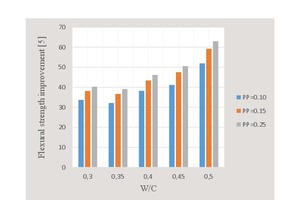

If fiber passes vertically across the edges of cracks, the integrity of the concrete will remain intact despite substantial deformation, because the fiber bridging the cracks practically “sews” the two sides together, thus preserving the concrete’s flexural strength. Figure 14 shows how reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 in non-fibrous specimens improved their flexural strength by 68.31 %, and Figure 15 points out that, for a water/cement ratio of 0.3, adding 0.1 %, 0.15 % and 0.25 % fiber improved the flexural strength of the specimens by 33.66 %, 38.1 % and 40.26 %, respectively.

During flexural testing, the upper and lower cross-sectional axes of a prismatic specimen experience compression and tension, respectively. Thanks to the high tensile strength of fiber, the concrete’s inherent tensile weakness and flexural strength will both increase. Adding fiber to (plain) concrete, which by nature is a brittle material, increases the ductility of specimens and improves their flexural strength.

While adding up to 0.25 % fiber increases the flexural strength of the specimens, any further addition can be expected to have a detrimental effect on flexural strength. This behavior is attributable to unsuitable distribution of fiber. The line of fracture passes approximately through the regions displaying low fiber density. In other words, the use of more than 0.25 % fiber subjects the specimens to the balling phenomenon, because excessive fiber content induces blockage within the concrete, hence practically eradicating the positive effects of fiber.

3.4 Abrasion resistance

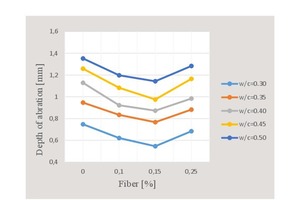

Figure 16 charts the abrasion depth of fibrous and non-fibrous specimens as a function of the water/cement ratio. Increasing the water/cement ratio incrementally from 0.3 to 0.5 is seen to alter the location and course of the abrasion depth curve in relation to the biphasic nature (mortar and aggregates) of concrete with abrasion exposure.

The abrasion resistance of the mortar phase decreases for higher water/cement ratios, while the abrasion resistance of the concrete approaches that of the aggregates.

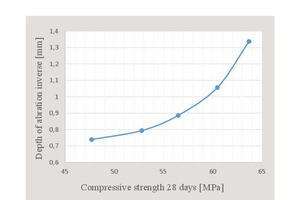

Figure 17 illustrates the compressive strength of 28-day concrete in dependence on the depth of abrasion. This shows that the abrasion resistance of concrete increases along with its compressive strength. In other words, factors that enhance the compressive strength of concrete also tend to improve its abrasion resistance.

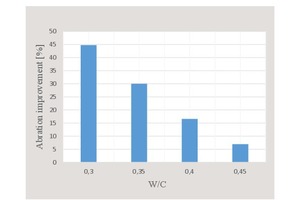

As illustrated in Figure 18, reducing the water/cement ratio for non-fibrous specimens from 0.5 to 0.3 improved their abrasion resistance by 44.71 %.

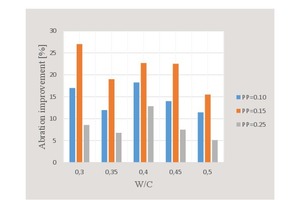

Figure 19 demonstrates how, for a water/cement ratio of 0.3, adding 0.1 %, 0.15 % or 0.25 % fiber to the specimens improved their abrasion resistance by 16.98 %, 27 % and 8.56 %, respectively.

Polypropylene fiber prevents water bleeding and transmission of water to the surface, hence improving the homogeneity of the concrete, the uniformity of the water/cement ratio in all parts of the specimen, and the continuity of hydration. Fiber also reduces the concrete’s surface permeability and improves its resistance to ageing and abrasion, thus helping to prevent disintegration and superficial lamination of the concrete.

Adding up to 0.15 % fiber increases the abrasion resistance of the specimens. However, adding more than 0.15 % fiber causes their abrasion resistance to diminish. Such behavior on the part of concrete specimens is attributable to a porosity increment resulting from excessive fiber content and the absence of polymer admixtures that would help achieve proper cohesion between the fiber and the concrete matrix. Consequently, an appropriate option for improving the abrasion resistance of concrete is to provide for suitable cohesion between fiber and concrete, either by way of the specimen geometry or by adding polymeric material.

3.5 Hydraulic conductivity coefficient

and porosity

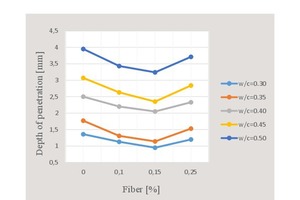

Figure 20 depicts the variation curve of water penetration depth into fibrous and non-fibrous specimens for different water/cement ratios.

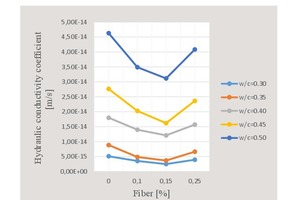

Figure 21 illustrates how the coefficient of hydraulic conductivity of fibrous and non-fibrous specimens depends on the water/cement ratio. The hydraulic conductivity coefficient of concrete increases with each increase in water/cement ratio. Reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 for non-fibrous specimens was seen to lower the concrete’s conductivity coefficient from 46.28 x 10-15 to 5.1 x 10-15.

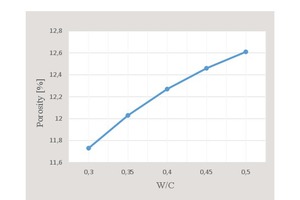

The link between the porosity of non-fibrous specimens and their water/cement ratio is depicted in Figure 22. The porosity of the concrete was seen to increase almost linearly with the water/cement ratio. Reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 lowered the porosity of the concrete from 12.61 % to 11.73 %.

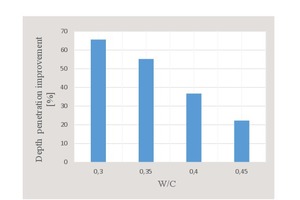

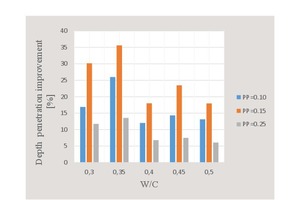

Figure 23 shows how reducing the water/cement ratio from 0.5 to 0.3 for non-fibrous specimens improved the depth of water penetration by 65.57 %.

Figure 24 points out that, for a water/cement ratio of 0.3, adding 0.1 %, 0.15 % and 0.25 % fiber to the specimens improved their depth of water penetration by 16.91 %, 30.15 % and 11.76 %, respectively.

The reason why the presence of fiber reduces the penetration depth of water is that the individual fibers tend to obstruct the pore connection paths, hence accordingly reducing their capillarity as a resonant factor of permeability.

Adding up to 0.15 % fiber reduces the penetration depth of water and, hence the permeability of the specimens. If, however, more than 0.15% fiber is introduced, those factors will increase due to higher porosity resulting from the presence of excessive fiber.

The data shown in Table 4 are needed for obtaining the hydraulic conductivity coefficient and porosity of nano-silica concrete.

4 Conclusions

In due consideration of previous investigations, the present research and test series yielded the following findings:

Adding 0.1 % fiber increases the compressive strength at 7, 28 and 90 days. More than 0.1% fiber reduces the compressive strength of specimens at any age due to unsuitable distribution of fiber. Adding a constant proportion of superplasticizer while increasing the fiber content decreases the slump of concrete and effects a reduction in the compressive strength of the specimens. The porosity of concrete specimens is increased by addition of fiber

0.1 % addition of fiber has a positive effect on tensile and flexural strength. Higher proportions of fiber increase the tensile strength of the specimens, albeit with a lower run of the curve

Adding up to 0.25 % fiber increases the tensile and flexural strength of specimens. It is expected that the tensile and flexural strength of specimens will decrease, if more than 0.25 % of fiber is used. This behavior is due to unsuitable distribution of fiber, as to be seen on the visible surface of those specimens. The line of fracture passes approximately through the regions displaying low fiber density. In other words, the use of more than 0.25 % fiber subjects the specimens to the balling phenomenon, because excessive fiber content induces blockage within the concrete, hence practically eradicating the positive effects of fiber.

Specimens containing fiber display two principal status relationships between cracks and fiber: vertical and horizontal. If fiber passes vertically across the edges of cracks, the integrity of the concrete will remain intact despite substantial deformation, because the fiber bridging the cracks practically “sews” the two sides together, thus preserving the concrete’s flexural strength

During flexural testing, the upper and lower cross-sectional axes of a prismatic specimen experience compression and tension, respectively. Thanks to the high tensile strength of fiber, the concrete’s inherent tensile weakness and flexural strength will both increase. Adding fiber to (plain) concrete, which by nature is a brittle material, increases the ductility of the specimens and improves their flexural strength

The run of the abrasion depth curve is lowered by increasing the water/cement ratio from 0.3 to 0.5. This can be attributed to the biphasic (mortar and aggregates) nature of concrete in abrasion. The abrasion resistance of the mortar phase decreases in reaction to any increase in the water/cement ratio, and the abrasion resistance of the concrete approaches that of the aggregates. Therefore, to increase the abrasion resistance of concrete, the mortar and aggregates should be reinforced together. The mortar phase can be improved by reducing the water/cement ratio, adding nano-silica and/or polypropylene fiber, and ensuring proper, timely curing. The aggregate phase, in turn, can be improved by including abrasion-resistant aggregates

The abrasion resistance of concrete increases along with its compressive strength. In other words, factors that enhance the compressive strength of concrete also tend to improve its abrasion resistance.

Polypropylene fiber prevents water bleeding and transmission of water to the surface, hence improving the homogeneity of the concrete, the uniformity of the water/cement ratio in all parts of the specimen, and the continuity of hydration. Fiber also reduces the concrete’s surface permeability and improves its resistance to ageing and abrasion, thus helping to prevent disintegration and superficial lamination of the concrete.

Adding up to 0.15 % fiber increases the abrasion resistance of the specimens. However, adding more than 0.15 % fiber causes their abrasion resistance to diminish. Such behavior on the part of concrete specimens is attributable to a porosity increment resulting from excessive fiber content and the absence of polymer admixtures that would help achieve proper cohesion between the fiber and the concrete matrix. Consequently, an appropriate option for improving the abrasion resistance of concrete is to provide for suitable cohesion between fiber and concrete, either by way of the specimen geometry or by adding polymeric material.

The reason why the presence of fiber reduces the penetration depth of water is that the individual fibers tend to obstruct the pore connection paths, hence accordingly reducing their capillarity as a resonant factor of permeability.

Adding up to 0.15 % fiber reduces the penetration depth of water and, hence the permeability of the specimens. If, however, more than 0.15 % fiber is introduced, those factors will increase due to higher porosity resulting from the presence of excessive fiber.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.