Effect of calcium carbide slag on the durability of alkali-activated ground granulated blast furnace slag-fly ash cementitious system

In this paper, alkali-activated composite cementitious materials were prepared by using calcium carbide slag, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), and fly ash as raw materials, and a combination of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate solutions were used as alkali activators of binders. The drying shrinkage, resistance to chlorine ion permeability, sulfate resistance, and mechanical properties of GGBS-fly ash cementitious system with different contents of calcium carbide slag were investigated. In addition, the changes in hydration products were also analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The results show that: when the content of calcium carbide slag instead of fly ash or GGBS is gradually increased, the drying shrinkage of the composite cementitious material decreases dramatically, the compressive strength and flexural strengths corrosion resistance coefficient increase first and then decrease, the compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficient decreases weakly. The primary hydration products of the composite cementitious material with varying calcium carbide slag content are calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) and these products remain stable under sodium sulfate erosion. Overall, the optimal properties were achieved with 3% calcium carbide slag replacing fly ash, which exhibits a 28 d drying shrinkage of 9672 με, an electrical flux of 2868 C, a compressive strength of 67.3 MPa after 120 d of full immersion in sodium sulfate, a flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient of 1.21, and a compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficient of 1.02.

1 Introduction

Portland cement is the most widely used building material, and Chinese cement output has reached 2.02 billion t in 2023. The production process of 1 t of cement generates about 810 kg of carbon dioxide, 1.0 kg of sulfur dioxide, and 2.0 kg of nitrogen oxides [1], and the emission of these air pollutant gases poses significant challenge to environmental governance. The alkali-activated cementitious materials, however, take natural silica-aluminate materials (e.g., kaolin, metakaolin) or solid wastes (e.g., fly ash, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), steel slag) as...

1 Introduction

Portland cement is the most widely used building material, and Chinese cement output has reached 2.02 billion t in 2023. The production process of 1 t of cement generates about 810 kg of carbon dioxide, 1.0 kg of sulfur dioxide, and 2.0 kg of nitrogen oxides [1], and the emission of these air pollutant gases poses significant challenge to environmental governance. The alkali-activated cementitious materials, however, take natural silica-aluminate materials (e.g., kaolin, metakaolin) or solid wastes (e.g., fly ash, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), steel slag) as precursors, and activate their potential activity through alkaline activators, which have the advantages of low carbon emissions, environmental protection [2], and excellent durability [3-5].

Calcium carbide slag (CS) is a waste residue composed mainly of calcium hydroxide, which is generated after the hydrolysis of calcium carbide to produce acetylene [6]. Currently, calcium carbide slag is primarily disposed of by stacking and landfill, which not only occupies a large amount of land resources but also causes serious soil and water pollution due to its long-term stacking and its strong alkalinity (pH >12) [7-9]. The strong alkalinity of calcium carbide slag can promote the reaction between precursors and alkali activator [10], or it can be directly used as an alkali activator to prepare alkali-activated cementitious materials. Cong et al. [11] and An et al. [12] both prepared alkali-activated fly ash-slag based composite cementitious materials using calcium carbide slag as an alkali activator, and found that calcium carbide slag can provide an alkaline environment required for the hydration of the composite cementitious materials. However, the excessive amount of calcium carbide slag can lead to a loss of strength in the specimens, and the mechanical properties of the sample were poor when calcium carbide slag was used as the alkali activator alone. Shi et al. [13] investigated the feasibility of a red mud-calcium carbide slag synergistically activated fly ash-GGBS based eco-friendly geopolymer, the best properties of the geopolymer were obtained after 12 h of heat curing, making it suitable for the production of low carbon concrete blocks. Liu et al. [14, 15] studied the effect of different calcium carbide slag contents on the compressive strength and carbonation resistance of alkali-activated fly ash-slag-calcium carbide slag based composite cementitious materials, and pointed out that calcium carbide slag can enhance the compressive strength of the specimens when it is incorporated by replacing the fly ash, but it is not conducive to the development of compressive strength when it is added by replacing the GGBS. Moreover, the addition of calcium carbide slag can improve the carbonation resistance of the specimen.

In summary, some scholars have conducted studies on alkali-activated calcium carbide slag - GGBS-fly ash based composite cementitious materials for a certain study. However, these studies have mainly focused on the preparation of composite cementitious materials and their hydration mechanisms, with a lack of research on durability. Based on this, in this paper, a sodium silicate solution-sodium hydroxide mixture solution was used to active the calcium carbide slag-GGBS-fly ash based composite cementitious material to investigate the effect of calcium carbide slag incorporation on its drying shrinkage, resistance to chloride penetration, and sulfate resistance. In addition, the changes in hydration products were also characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to analyze the mechanism behind calcium carbide slag on the durability of alkali-activated ground granulated blast furnace slag -fly ash cementitious system.

2 Materials and methodology

2.1 Materials

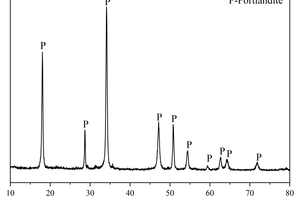

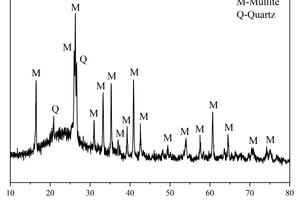

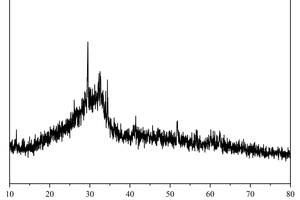

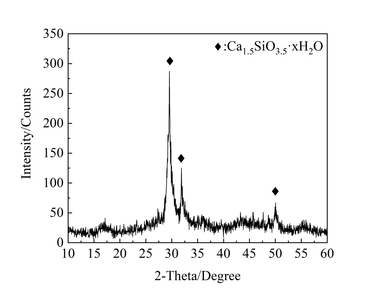

The main chemical compositions and XRD patterns of calcium carbide slag (CS), ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) and fly ash (FA) are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively. It can be observed from Figure 1 that the principal crystalline phase in CS is portlandite, the principal crystalline phases in FA are mullite and quartz, whereas GGBS has a large number of diffuse peaks, indicating the main phases of GGBS are glassy state, with fewer crystalline substances. Sodium silicate solution (with 30.0 wt.% SiO2, 13.5 wt.% Na2O, and 56.5 wt.% H2O) was obtained from a local distributor. NaOH was analytically pure flake sodium hydroxide produced by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. The Sodium silicate solution modulus was adjusted to 1.5 as an alkali activator by mixing with solid NaOH [16]. The alkaline activators were applied in this study at a content of 4 wt.% Na2O relative to the mass of solid precursors (CS + GGBS + FA).

2.2 Experimental program and testing methods

The raw materials were first dry mixed according to the mix proportions shown in Table 2. Then the prepared sodium silicate solution was added to the mixer and stirred evenly to create paste mixtures, which were injected into the molds, and the specimens were demolded after extending the maintenance time to 36 h due to difficulty in demolding the specimens after 24 h of the standard maintenance (20 ± 1 °C, RH ≥ 90%).

2.2.1 Drying shrinkage

The drying shrinkage test was carried out according to Chinese standard JC/T 603-2004 with molds of 25 mm × 25 mm × 280 mm, and the specimen was moved to a drying oven with a temperature of (20±2) °C and a relative humidity of (50±5)% after demolding. After curing to the specified age, the length of the specimen was measured with a cement mortar comparator to calculate the drying shrinkage rate.

2.2.2 Chloride penetration resistance

Referring to the Chinese standard GB/T 50082-2009, the resistance to chloride permeability was evaluated using the electric flux method by cylindrical specimens with a diameter of (100±1) mm and a height of (50±2) mm. After demolding, the specimens were cured for 28 d before conducting the electric flux test.

2.2.3 Sulfate resistance

The sample size for the sulfate attack test was 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm. After the specimens were detached from the mold and placed in water at (20±1) °C for curing for 28 d, they were soaked in 5% Na2SO4 solution for the sulfate attack test. The sulfate attack test was divided into two distinct categories: the full-immersion test and the semi-immersion test. In the semi-immersion test, the specimens were vertically immersed in the erosion solution, with an immersion depth of 80 mm. To ensure the accuracy of the test results, the erosion test process was designed to maintain a constant depth of immersion, and the erosion solution was replaced once a month. After 30 d, 60 d, and 120 d of erosion, the specimens were removed for testing of flexural and compressive strengths. The flexural and compressive strengths were tested in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 17671-2021, using a loading rate of 50 N/s for the flexural strength test and 2400 N/s for the compressive strength test.

2.2.4 XRD analysis

Some small pieces from the broken specimen of the compressive strength test were selected and the hydration of them was terminated with anhydrous ethanol. Then some of them were ground and dried for XRD analysis by a Bruker D8 Advance type X-ray diffractometer from Germany with a scanning rate of 8°/min.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Drying shrinkage

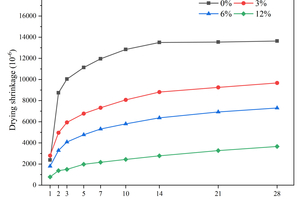

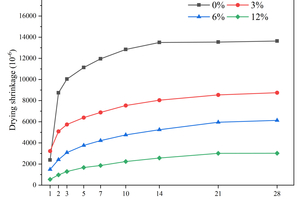

Drying shrinkage primarily occurs due to the loss of water from the interior of the specimens to the environment through evaporation, and the removal of water from the capillary pores would cause capillary stress, which is a major driving force for drying shrinkage [17]. Figure 2 shows the drying shrinkage of the specimens with different contents of CS replacing FA in equal mass for 28 d.

From Figure 2, it can be observed that the control group without the inclusion of CS exhibits the highest drying shrinkage, reaching 13639 με at 28 d. The drying shrinkages at 28 d for 3% and 12% CS inclusion are 9672 με and 3660 με, respectively, which are 29.09% and 73.17% lower than that of the control group. This indicates that the inclusion of CS instead of FA significantly inhibits the drying shrinkage of the specimens, which is attributed to the large amount of Ca(OH)2 in CS. Firstly, the calcium introduced by adding Ca(OH)2 increases the Ca/Si ratio of the C-(A)-S-H gel [18, 19], and the increase in the Ca/Si ratio enhances the water retention of the C-(A)-S-H gel [19]. As a result, the loss of water during drying is reduced, which decreases the drying shrinkage. Secondly, the increased presence of Ca(OH)2 crystalline phase enhances the stiffness of the specimens and improves their elastic modulus [20], thereby limiting the drying shrinkage.

Figure 3 shows the drying shrinkage of the specimens with different contents of CS replacing GGBS in equal mass over 28 d.

It is obvious from Figure 3 that the drying shrinkage of the specimens at 28 d decreases gradually as the content of CS increases, which follows the same trend as when CS replaces FA. The 28 d drying shrinkages of the specimens with 3%, 6%, and 12% CS content are 35.85%, 55.03%, and 77.85%, respectively, lower than that without CS. Comparing Figure 3 and Figure 2, it can be observed that the decrease in drying shrinkage of the CS replacing GGBS is more pronounced compared to that of the CS replacing FA. Specifically, at 12% calcium carbide slag content, the dry shrinkage of the former decreases by 4.68% more than the latter. This can be attributed to the reduction of the content of GGBS, which slows down the initial hydration rate and reduces the amount of hydration products of C-(A)-S-H gels. During drying, the C-A-S-H gel tends to collapse and redistribute [21], so the reduction of the C-A-S-H gel decreases some of the drying shrinkage.

3.2 Chloride penetration resistance

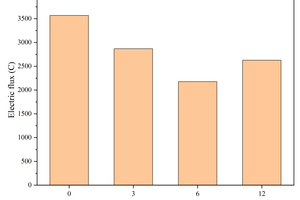

Figure 4 shows the effect of replacing FA with different contents of CS on the electrical flux of the specimens.

Electrical flux is a test based on electrical conductivity measurements, which is mainly influenced by the pore structure of the paste and the chemical composition of the pore solution [22]. It can be observed from Figure 4 that the increased content of CS leads to a decrease followed by an increase in the electrical flux of the specimens. For instance, when the calcium carbide slag content is 0%, 3% and 6%, the electric flux is 3567 C, 2868 C and 2178 C, respectively, showing a decreasing trend, while when the calcium carbide slag content is increased to 12%, the electric flux is increased to 2627 C. This is because the addition of CS promotes hydration, increases the amount of hydration products, refines the pore structure, and thus reduces the electrical flux. Additionally, the incorporation of CS reduces the shrinkage of the specimens, leading to fewer micro-cracks and decreased inter-pore connectivity, which also reduces the electrical flux. However, as the CS content continues to increase, the alkalinity and ionic concentration of the pore solution rise. Consequently, the conductivity of the pore solution increases, leading to higher electrical flux.

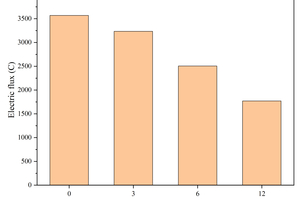

Figure 5 shows the effect of replacing GGBS with different contents of CS on the electrical flux of the specimens.

It is significant from Figure 5 that the electrical flux of the specimen continues to decrease as the CS content replacing GGBS increases. For example, the electric flux of the sample with 12% calcium carbide slag is reduced by 50.39% compared with that without calcium carbide slag. The decreasing of electrical flux caused by CS is mainly because it can promote hydration, reduce shrinkage, and optimize the pore structure, thereby enhance resistance to chloride ion permeability of the cementitious system. Additionally, from the XRD analysis in section 3.4.3, it is evident that when the same content of CS is used to replace FA and GGBS, the CS used to replace GGBS is more consumed in the early hydration of the GGBS. As a result, the effect of CS on the ion concentration of the pore solution is reduced, making the electrical flux of the specimen with 12% CS replacing GGBS relatively smaller compared to that of the specimens replacing FA.

3.3 Effect of the amount of CS replacing FA

on sulfate attack

3.3.1 Flexural/compressive strengths

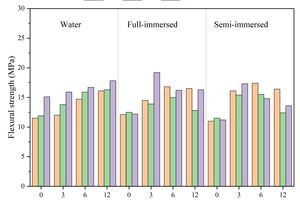

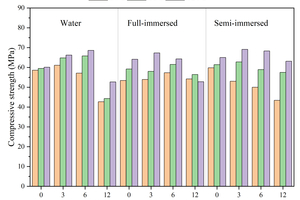

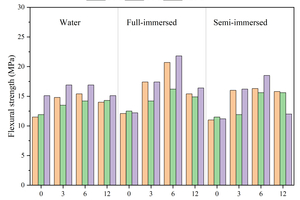

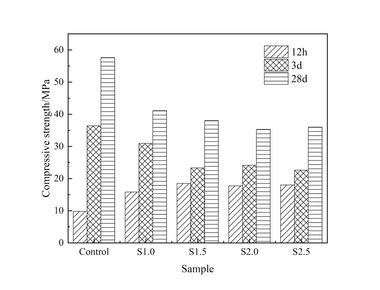

Figure 6 shows the flexural and compressive strengths of specimens with different CS content replacing FA at different ages after curing in water, and full and semi-immersion in sodium sulfate attack solution.

The results show that the flexural strength of the specimens at each age gradually increases with the increase in CS content under the condition of water curing. The flexural strength of the specimen with 12% CS content reaches 17.8 MPa at 120 d (120 d is the age of erosion, and the actual age is 148 d), which is an increase of 17.9% compared to that without CS. The compressive strength first increases and then decreases with the rise in CS content, and the specimen with 6% CS content shows the highest compressive strength, reaching 68.6 MPa. This is because CS contains a large amount of Ca(OH)2, which can dissociate hydroxide ions to promote the hydration of GGBS and the pozzolanic reaction of FA, thereby increasing the hydration products. When the CS content exceeds 6%, the compressive strength at 120 d begins to decrease. This is due to excessive CS admixture causing a shortening of setting time and loss of fluidity, which may lead to defects in the specimens and thus reduce their strength. Additionally, since CS does not have activity, a higher CS content means a reduction in FA content, resulting in a decreased compressive strength.

Under the erosion environment of sodium sulfate, with the increase in CS content, the flexural strength first increases and then decreases, and they are all greater than the flexural strength of specimens without CS. For instance, the specimen with 3% CS under full immersion for 120 d reaches a maximum flexural strength of 19.2 MPa. Under full immersion erosion in sodium sulfate, the compressive strength exhibits a similar pattern to that of water curing, first increasing and then decreasing. Specifically, the maximum compressive strength of the sample with 3% calcium carbide slag is 67.3 MPa after 120 d of erosion. However, after 30 d of semi-immersion erosion, the compressive strength gradually decreases with the increased CS content, with the compressive strength of the specimen containing 12% CS decreasing by 16.4 MPa compared to that without CS, and after 120 d of semi-immersion erosion, the compressive strength again increases and then decreases, with the specimen containing 12% CS showing a reduction of 1.9 MPa compared to that without CS. This behavior is attributed to the fact that after incorporating CS instead of FA, the unreacted CS in the early stage continues to participate in hydration in the later stage, promoting the development of strength, as demonstrated in the subsequent XRD analysis.

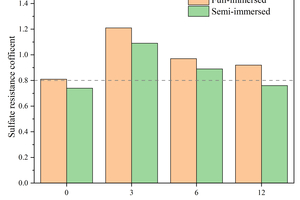

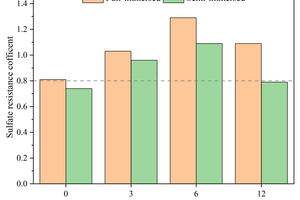

3.3.2 Sulfate resistance coefficient

Figure 7 shows the flexural and compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficients of specimens with different CS contents replacing FA after 120 d of sodium sulfate attack. In general, alkali-activated cementitious materials with a corrosion resistance coefficient greater than 0.8 are considered to have excellent sulfate resistance.

It can be observed from Figure 7 that the content of 3% CS significantly enhances the flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient of the specimens, while the compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficient shows only a minor decrease, with full and semi-immersion flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficients of 1.21 and 1.09, respectively, and compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficients of 1.02 and 1.04. In addition, it is observed that specimens with each CS content exhibit higher flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficients when fully immersed. This phenomenon is attributed to the “wick effect” in the evaporation zone of the sodium sulfate semi-immersion, which accelerates the migration of erosion ions and leads to the formation of a pore solution area with high sulfate concentration [23]. Consequently, physical attack from sulfate crystallization occurs in the middle section of the specimens, resulting in microcracks that decrease flexural strength.

By combining flexural strength, compressive strength, and corrosion resistance coefficients, it can be concluded that specimens with 3% FA replaced by CS exhibit the best resistance to sodium sulfate erosion.

3.3.3 XRD analysis

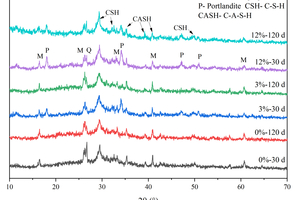

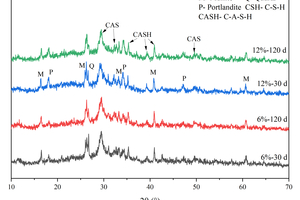

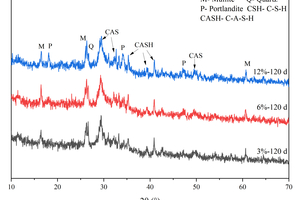

Figure 8 shows the XRD patterns of specimens with different CS content after water curing and full immersion in sulfate.

As shown in Figure 8, diffraction peaks of mullite and quartz are observed, indicating the presence of unreacted FA in the system. Additionally, a large number of continuous diffuse peaks is seen in the XRD pattern, with an obvious broad hump in the diffraction angle range of 25°-35°, characteristic of the main hydration products, C-S-H/C-A-S-H amorphous gels [24, 25]. Under the condition of water curing, prominent Ca(OH)2 (Portlandite) diffraction peaks can be observed near 18.2° and 34.2° with the increase of CS content at 30 d, which indicates that there is still a significant amount of unreacted CS in the system at this time. However, at 120 d, the Ca(OH)2 diffraction peaks of the specimen containing 3% CS are no longer observed, and the Ca(OH)2 diffraction peaks of the specimen mixed with 12% CS decrease significantly compared to the specimen at 30 d, mainly because the pozzolanic reaction of FA can consume Ca(OH)2 to produce the hydration products of C-A-S-H gels. By comparing the XRD patterns of different CS content at 30 d and 120 d, it can be found that the C-A-S-H characteristic peaks of hydration products are more intense at 120 d.

The XRD pattern after 120 d of sulfate attack is shown in Figure 8 (b). Comparing Figure 8 (a) and Figure 8 (b), it can be observed that sulfate attack products such as ettringite and gypsum are not produced after 120 d of immersion in Na2SO4. The C-S-H/C-A-S-H gels remain stable under the attack of sodium sulfate, which is consistent with the results of Zhang et al [26].

3.4 Effect of the amount of CS replacing GGBS

on sulfate attack

3.4.1 Flexural/compressive strengths

Figure 9 shows the flexural and compressive strengths of specimens with different CS content replacing GGBS at different ages after water curing, and full and semi-immersion in sodium sulfate.

As shown in Fig. 9, with the increase of CS content, the flexural and compressive strengths of each age group first increase and then decrease under water curing condition. The compressive strength starts to decrease sharply after the CS content exceeds 3%. At 120 d, the compressive strength reaches a maximum of 65.2 MPa at 3% CS content and then decreases to 41.9 MPa at 12%, resulting in a compressive strength loss of 35.7%. This trend is similar to the aforementioned one of CS replacing FA specimens. It is noted that with 12% CS content, the compressive strength first decreases and then increases with the age, with the 60 d and 120 d compressive strengths lower than the 30 d compressive strength, which suggests that excessive CS replacing GGBS hinders strength development [27].

Under the condition of full immersion in sodium sulfate, as the content of CS increases, the flexural and compressive strengths first increase and then decrease. For instance, the flexural strength at 3% CS content is 17.4 MPa, and the compressive strength is 67.1 MPa, which were 42.6% and 4.7% higher than those of the specimens without CS, respectively.

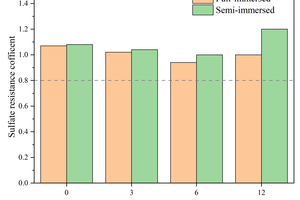

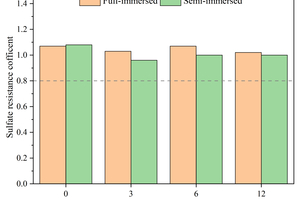

3.4.2 Sulfate resistance coefficient

Figure 10 shows the flexural/compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficients of specimens after 120 d of sodium sulfate erosion with different contents of CS replacing GGBS.

It can be seen from Figure 10 that the addition of CS can improve the flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient. The flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient of the full-immersion specimen without CS was 0.81, while it increases to 1.29 in the specimen with 6% CS. On the other hand, the compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficient of the specimen with CS is lower than that without CS, and there is only a slight decrease in full immersion, but the decrease is more pronounced in semi-immersion. For instance, the compressive strength corrosion resistance coefficient is 0.96 in the specimen of semi-immersion with 3% CS, which is 11.1% lower than that without CS.

By combining the flexural and compressive strength with the corresponding corrosion resistance coefficients, it can be concluded that the specimen with 6% GGBS replaced by CS exhibits the best resistance to sodium sulfate erosion.

3.4.3 XRD analysis

Figure 11 presents the XRD patterns of specimens with different CS contents replacing GGBS, both after water curing and full immersion in sodium sulfate.

From Figure 11, it can be observed that there is no significant difference in the main hydration products among specimens with varying CS contents replacing GGBS. The Ca(OH)2 diffraction peaks only decrease slightly with prolonged curing age at different CS contents, and the primary diffraction peaks of C-S-H/C-A-S-H gels remain largely unchanged. Comparing Figure 11 (a) with Figure 8 (a), it is evident that the Ca(OH)2 diffraction peaks for the specimen with 12% CS replacing GGBS are significantly lower than those for specimen with 12% CS replacing FA at 30 d, indicating that that when CS replaces GGBS, the activation effect of CS mainly occurs in the early stage and the excess CS mainly acts as filling material in the late stage.

Comparing the XRD patterns from full immersion in sodium sulfate with those from water curing, it can be observed that no new products emerge after 120 d of sodium sulfate immersion. Additionally, there are no significant changes in the diffraction peaks of the main hydration products of C-S-H/C-A-S-H gels, which demonstrate that the system has excellent resistance to sodium sulfate attack when GGBS is replaced by CS.

4 Conclusions

1. The inclusion of CS in place of FA or GGBS can reduce the specimens‘ drying shrinkage and electric flux. Notably, replacing GGBS with CS has a more significant effect on reducing drying shrinkage. Specifically, for specimens with 12% CS replacing GGBS, the drying shrinkage at 28 d decreases by up to 77.85% compared to specimens without CS, and the electric flux decreases by 50.39%.

2. When CS replaced FA, both the compressive strength and flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient of the specimens initially increase and then decrease with the increasing content of CS. The specimen of 3% CS replacing FA enhances both the mechanical properties and the resistance to sodium sulfate erosion. After full immersion in a 5% sodium sulfate solution for 120 d, the maximum flexural strength of the specimen reach 19.2 MPa, and the compressive strength reach 67.3 MPa.

3. Semi-immersion erosion causes more severe erosion damage than full-immersion erosion. In the semi-immersion sodium sulfate attack environment, the sulfate crystallization damage caused by the “wick effect” resulted in a lower flexural strength corrosion resistance coefficient of 120 d than that of the full-immersion environment specimens.

4. The results of XRD analysis indicate that when CS partially replaces FA, it promotes the late pozzolanic reaction of FA, resulting in an increased amount of C-A-S-H gel. Conversely, when CS partially replaces GGBS, it primarily enhances the geopolymerization reaction in the early stages, with the excess CS mainly acting as a filler material in the later stages.

5 Acknowledgement

Financial support from the Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2023DJC182), the Hubei Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Science and Technology Plan Project ([2023] 1656-075), “The 14th Five Year Plan” Hubei Provincial advantaged characteristic disciplines (groups) project of Wuhan University of Science and Technology (2023D0501; 2023D0503) and the Hubei Provincial Excellent Young and Middle aged Science and Technology Innovation Team Project of Colleges and Universities (T2022002) are gratefully acknowledged.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.