Evaluation of the performance of multi‑component cements

Multi-component cements (“CEM X”) do not differ in their behaviour and performance in concrete from those cements already defined in the cement standards. Their constituents are well known and have been used successfully for a long time. Only the composition has not yet been covered by the cement standards.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

In the future, it can be assumed that further reduction of the clinker factor in cement will be necessary, particularly from the aspect of the increasing requirements to reduce CO2 emissions in cement production. This will cause an increased demand for alternative cementitious materials, such as granulated blast furnace slag or fly ash. These substances are secondary materials from other industrial production processes. Thus their availability depends on, among other things, economic and seasonal factors. This is confirmed by practical experience during recent years.

In order to fulfil their future responsibilities, cement producers need to have a high degree of flexibility in the selection and use of suitable materials. Only in this way, it will be possible to offer products of constant quality and performance that satisfy market demands against the background of frequently changing conditions. This is also a precondition for the competitiveness of cement and concrete with view on cost-effectiveness and sustainability when compared with other construction materials.

2 Definition of multi-component cements

3 Multi-component cements in current

cement standards

From consultations that are already well advanced, it can be expected that in future it will also be possible to use ground limestone as another component for ternary blended cements specified in this standard. The upper limit for the limestone content will probably be 15 % by mass. However, there is only limited experience in a few markets (e.g. Indonesia) with the production and use of multi-component cements conforming to ASTM C595.

The European cement standard EN 197-1 “Cement – Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria of common cement” defines cements with at least two other main constituents apart from clinker as Portland-composite cements of type CEM II-M. Depending on the level of the clinker content a distinction is made between the sub-classes CEM II/A-M and CEM II/B-M (Table 1). The maximum clinker reduction is 35 % by mass. In addition to clinker, all components standardized as main constituents may be used – (granulated blast furnace slag (S), fly ash (V/W), limestone (L/LL), pozzolanas (P/Q), silica fume (D), burnt shale (T)). Most frequently used combinations are slag/limestone (S-L/LL), fly ash/limestone (V-L/LL) and slag/fly ash (S-V). There is already some experience with these cements in various markets [4].

Composite cements CEM V according to EN 197-1, offer opportunities for greater clinker replacement by several other cement components (Table 2). They permit the combination of granulated blast furnace slag and pozzolanas. Positive application results, particularly with CEM V/A, have been obtained e.g. in France, The Netherlands or Poland. In these cases usually up to 50 % by mass of the clinker is replaced by a combination of granulated blast furnace slag and siliceous fly ash (fly ash from bituminous coal). A further option of combining different pozzolanas is the group of pozzolanic cements (CEM IV).

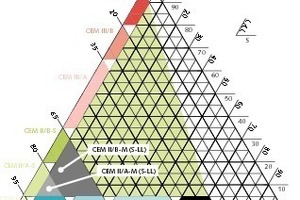

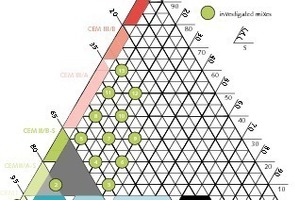

EN 197-1 was elaborated with the intention to cover all the cements that at that time were considered as traditional and well-tried in the CEN member states. On this basis the standard defines a total of 27 types of cement. In spite of this, the regulations contained in the current EN 197-1 cover a comparatively small range of the cement compositions that are theoretically possible. This is shown by the example of the combination of the three cement main constituents clinker, granulated blast furnace slag and limestone (Fig. 1).

Starting from Portland cement CEM I in the lower left-hand corner the various CEM II-S and CEM III cements that contain slag extend along the axis between 100 % by mass clinker (K) and 100 % by mass granulated blast furnace slag (S). Similarly, the possible compositions of the Portland limestone cements CEM II-LL are located on the horizontal axis between 100 % by mass clinker (K) and 100 % by mass limestone (L or LL). Masonry cements (MC) as specified in EN 413-1 have been added for clarity.

The Portland composite cements CEM II-M, which are the only ones so far that defined the combination of both ground limestone and granulated blast furnace slag as cement main constituents, can be found in the left-hand lower corner area of this three-phase diagram. The very restricted space in the cement composition especially for CEM II/A-M (S-LL) cement becomes clear in this form of presentation.

There remains a large area of possible compositions, shaded in yellow, that are not yet covered by cement standards. The same also applies to other multi-component cements, such as containing the combination of granulated blast furnace slag and fly ash or of fly ash and limestone. However, not all these possible variations produce cements that exhibit marketable and competitive performance and can ensure the necessary structural safety when used in concrete. Against this background there have already been initial considerations and investigations on the question which multi-component cements appear to be suitable and feasible [5]. It is not yet clear how these cements could be integrated into the existing cement classification scheme. Thus, normally the working title “CEM X” is used.

4 Investigation programme

The test cements were mixed in the laboratory from separately ground constituents. The finenesses of the components were chosen to correspond approximately to those that would be expected by industrial production. A factory produced Portland cement CEM I 52,5 R (C3S: 64 % by mass, C3A: 9 % by mass, Na2O: 0.57 % by mass) with a fineness of 5970 cm2/g according to Blaine was selected for the clinker fraction. Ground granulated blast furnace slag ((CaO + MgO)/SiO2: 1.32, Al2O3: 11 % by mass, fineness: 4460 cm2/g) was ground from a slag of normal hydraulic reactivity. The properties of the ground limestone (CaCO3: 96 % by mass, fineness: 6800 cm2/g) fulfilled all requirements of the LL category in EN 197-1. Calcium sulfate in the form of a mixture of anhydrite and hemihydrate was added to all the test cements to give the same total SO3 content compared to the reference cement CEM I 52,5 R.

The usual standard tests required by EN 197-1 were carried out with all test cements. The standard strengths of mortars tested according to EN 196-1 at 2 and 28 days are compiled in Table 3. As expected, the early strengths after 2 days decreases in comparison with the CEM I 52,5 R reference cement with decreasing clinker content. The respective amount of slag and limestone are of secondary importance. With the exception of the cements with a low clinker content of 30 % by mass (mixes 12 and 13) all the CEM X cements exhibit an early strength of more than 10 MPa. At 28 days the content of granulated blast furnace slag and ground limestone have a greater influence on the mortar compressive strength. A higher content of slag can compensate for the lower strength contribution of the limestone.

The test cements were categorized according to the strength classes in EN 197-1 on the basis of the measured strengths. Because of their low early strengths the test cements with a low clinker content of 30 % by mass (mixes 12 and 13) could only be allocated to class 32,5 N. However, all the rest of the CEM X cements fulfil the requirements of the 42,5 N strength class. Cements with a clinker content of 60 % by mass even reach higher classes. All the other parameters investigated (water demand, setting, soundness, etc.) fulfil the standard requirements and are in the same range as the usual standard cements.

When evaluating the test results, it has to be considered that all the investigated test cements had finenesses that are in the range of Blaine specific surface areas of 5500 to 6500 cm2/g. This means greater energy consumption for the production of these cements and a reduction in mill capacity. Under some circumstances the use of very fine cements can have an unfavourable effect on the workability of the concrete. On the other hand it must be taken into consideration that in these investigations the constituents of the test cements were mixed with one another without any further adjustment. The optimization options that are normally available in practice, such as adjustment of the particle size distributions, optimization of the sulfate carrier, etc., were not utilized here.

Comparison of the European markets shows that there are not yet any common criteria for evaluating the durability properties of concrete. Based on differences in e.g. climatic conditions and the long-term experiences, different test methods, concrete compositions, and test criteria are in use. This makes it very difficult to evaluate results of a single test method solely on the basis of absolute measured values. Much more informative is the direct comparison with concretes whose performance has been proven in many years of practical experience. Therefore reference mixtures made with CEM I 52,5 (base cement for the test cements), CEM III/ A 42,5 N (40 % by mass of slag) and CEM III/B 32,5 N (70 % by mass of slag) were included in the investigations.

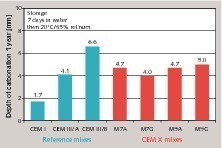

As expected, the CEM I Portland cement exhibited the lowest depth of carbonation when stored under laboratory climate. The depth of carbonation increased with decreasing clinker content in the cements. However, the differences between the various CEM X cements were very small. Under the conditions investigated here the varying qualities of granulated blast furnace slag and limestone seem to be of secondary importance. In general, the measured values for the CEM X cements are in the same range as the reference mix made with CEM III/A, which has a comparably high clinker content of 60 % by mass.

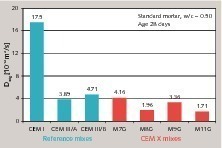

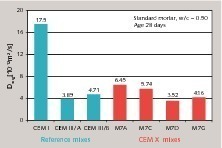

Figure 4 compares the measured chloride migration coefficients of the CEM X cements investigated with those of the reference mixes. The results confirm the general experience that blast furnace cements have a significantly higher resistance to chloride penetration than pure Portland cements. This finding is also applicable to CEM X cements, which show chloride migration coefficients of the same range as the reference cements containing slag. The lowest values were recorded for the cements containing the higher levels of slag (mixes M8 and M11).

Figure 5 deals with the influence of the properties of slag and limestone. Using the example of mix M7, which contains 30 % by mass of ground slag and 20 % by mass of limestone, it shows the chloride migration coefficients for the cements where the fineness of the ground slag or the quality of limestone was varied. The use of finely ground slag (M7D and M7G) tends to result in lower coefficients than the coarser material (M7A and M7C). The higher chemical reactivity of the ground slag caused by greater fineness becomes effective here. On the other hand, the quality of the limestone has no clearly identifiable influence when considering the possible variability of the applied test method.

The results illustrate the beneficial effect of granulated blast furnace slag on the resistance to the penetration of chlorides that also applies to multi-component cements. The content of slag and its reactivity are crucial. Experience shows that ground limestone does not contribute to improving the resistance to chloride penetration. However, the test results also indicate that even fairly high levels of limestone combined with granulated blast furnace slag do not have a detrimental effect on the measured values. In this respect the slag can compensate the lower effectiveness of limestone, although further research is required to clarify the exact mechanism. It is a matter of making efficient use of the positive synergy between the two materials.

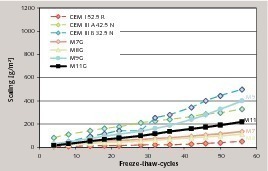

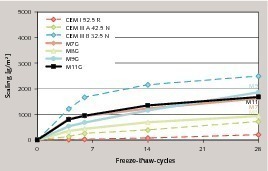

The freeze-thaw resistance was tested by the CF method, which is described in CEN/TS 12390-9 [7]. The one-sided test surface of the concrete samples is immersed in de-ionized water and subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles (2 cycles per day). The loss in weight of the samples is determined up to 56 freeze-thaw cycles. All the concretes investigated had the same mix composition with a cement content of 320 kg/m3 and a w/c ratio of 0.50. No air-entraining agents were added to the concretes. When they had been removed from the mould after 24 hours the samples remained under water for a further 6 days. They were then stored at 20 °C/ 65 % r.h. until the start of testing at the age of 28 days.

Figure 6 shows the development of the freeze-thaw scaling from concretes made with cements of different composition. The measured weight losses demonstrate that all the concretes could be classified as freeze-thaw resistant and follows the usual development of scaling observed in laboratory freeze-thaw testing. As expected, the concrete made with the CEM I 52,5 R reference cement has the lowest scaling in the laboratory test. The concretes made with the CEM III/A 42,5 and CEM III/B 32,5 N exhibit increasing weight losses corresponding to their slag contents. The scaling of concretes made with the CEM X mixes M7, M8 and M11 does not differ significantly within the limits of the usual variability of the test method. They are in the range between the values of the reference cements CEM I and CEM III/A. The limestone content, which was between 10 and 20 % by mass, has no detectable influence except that the scaling of mix M9 (K/S/LL = 40/30/30) is somewhat higher. This is the cement with the lowest clinker content and the highest limestone content. The values were of the same level as those of the CEM III/A.

Here again, the influence of the properties of the main cement constituents were examined in detail. For the cements with composition M7 only variant A exhibited fairly high scaling that is of the same range as the measured values for CEM III/B (Fig. 7). This cement contained the coarser ground slag and the limestone with a low calcium carbonate content.

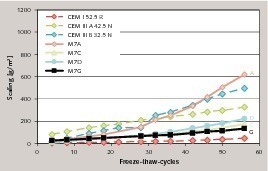

The results for the cements with the composition M9 with the highest limestone content of 30 % by mass give a clearer indication of the influence of the cement components (Fig. 8). A significant difference can be seen here between variants A and C (low slag fineness) on one hand and variants D and G (high slag fineness) on the other. This means that in these cements the reactivity of the granulated blast furnace slag, expressed here by the different finenesses of the identical material, has a substantial influence on the freeze-thaw resistance of the concrete. The influence of the quality of the limestone is of only secondary importance in spite of its high proportion in the cement. With mixtures A and D, each with a low CaCO3 content of the limestone, there was in fact a somewhat higher scaling than with the corresponding mixtures C and G with a high CaCO3 content. However, these differences are slight and within the usual variability of the test method.

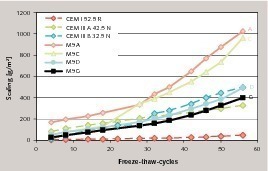

The development of scaling caused by exposure to freeze-thaw cycles with de-icing salt can be seen in Figure 9 for different cement compositions. Once again, the comparison with reference concretes made with various known cements is shown. Because of their scaling of less than 1000 g/m2 after 28 freeze-thaw cycles the concretes made with Portland cement CEM I and blast furnace cement CEM III/A can be classified as reliably freeze-thaw resistant. On the other hand, existing experience indicates that the concrete made with CEM III/B cement with scaling of more than 2000 g/m2 has only limited resistance to freeze-thaw and de-icing salt attack.

The concrete made with cement mix M8 exhibited scaling which is comparable with those of CEM III/A. The values measured for the other three concretes made with CEM X cements is in the range between CEM III/A and CEM III/B. There was hardly any difference in the scaling of these three concretes. The cement composition has no detectable influence – the limestone content varies between 10 and 30 % by mass.

It is not possible to make a definite assessment of the absolute freeze-thaw and de-icing salt resistance of the concretes investigated here. However, the results indicate that the concretes are at the limit of adequate freeze-thaw resistance. Here it is necessary to optimize the cement performance. And there is still space for potential improvements in the cement properties as the opportunities for optimization during the normal cement production process were not applied in the preparation of the laboratory cements.

5 Conclusions

The obtained test results as well as all the other existing experience confirm that the reaction mechanisms and performance of these multi-component cements in concrete do not differ from those of conventional cements. The setting, hardening, development of the microstructure, strength formation and durability follow the same principles and physical laws that are familiar from the cements based on Portland cement clinker already covered by the standard.

In most cases the investigated CEM X cements made from a combination of clinker, granulated blast furnace slag and limestone, reached strength class 42,5 N as defined in EN 197-1. This is the strength class in which many, and in some markets most of Portland-composite and blast furnace cements are used nowadays in normal concrete applications for structural concrete construction. Only cements with a very high level of clinker replacement failed this requirement due to their lower early strengths and thus were allocated to a lower strength class.

However, it must also be said that the majority of investigated cements had specific surface areas of more than 5500 cm2/g according to Blaine. This fineness is higher than the average value of the currently usual standard cements. This means that an increased grinding must be expected in cement production in order to produce cements with the required performance. This can cause an increase in energy consumption and a reduction in production capacity. A higher cement fineness can also affect the technological properties of concrete. In particular, the workability of the fresh concrete could be affected if cements with higher water demand are used.

To improve the production process and cement properties, further research and development work is necessary. However, this optimization process always has to be adapted to the specific plant conditions and the properties of the individual cement components. The cements used for the test programme described here were produced in the laboratory by simple mixing of a CEM I 52,5 R cement with granulated blast furnace slag and limestone that had each been ground separately. No other optimization apart from the addition of calcium sulfate was carried out. There is still significant space for improving the cement properties using the proven options for optimization in the cement production process.

Also with respect to durability familiar effects were found. For example, the CEM X cements exhibited the same beneficial effect in increasing the resistance to chloride penetration that is well known with the usual blast furnace cements. Higher limestone levels of up to 30 % by mass did not show an unfavourable effect. For the freeze-thaw resistance scaling was in the same range as those of conventional Portland-composite cements CEM II/B and blast furnace cements CEM III/A. During exposure of the concrete to the combined attack of freeze-thaw and de-icing salts scaling was higher than those of the CEM III/A blast furnace cement under the laboratory conditions tested here. Further investigations are needed to classify the resistance to freeze-thaw and de-icing salt attack.

6 Final assessment

When used in concrete the performance of multi-component cements is, depending on the cement composition, in the same range as for Portland-composite cements (CEM II/B) and blast furnace cements (CEM III/A, i.e. slag content up to 65 % by mass). In this paper results for the combination of granulated blast furnace slag (S) and limestone (LL) have been presented. The findings have to be transferred to other combinations, such as fly ash (V) and limestone (LL), but no fundamentally different results are to be expected. The main problem is determining the respective limits for clinker replacement without diminishing the performance of the cement.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.