Thermally induced changes in microstructure and their effects on the mechanical parameters of AAC

Summary: Investigations into the thermally induced changes in the microstructure of autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) were compared with the systematic determination of the parameters of high temperature stressing of the three currently most widely used types of aerated concrete (P2-0.35; P2-0.4 and P4-0.5) to gain an insight into how masonry made of aerated concrete would behave in the case of fire. The determination of temperature-dependent building material parameters in AAC has made a contribution to the creation of a systematic material database for the application of engineering methods of structural fire protection in accordance with Eurocode 6, Part 1–2.

Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) is an inorganic, mineral, walling material that unites a very favourable combination of the parameters of bulk density, compressive strength and thermal conductivity. Quartz sand, lime and/or cement as the binder, gypsum and/or anhydrite (depending on the mix formulation) and water are required for its production. The building material acquires its characteristic porous structure through the addition of aluminium powder, which reacts in the aqueous alkaline environment with the evolution of hydrogen and foams the...

Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) is an inorganic, mineral, walling material that unites a very favourable combination of the parameters of bulk density, compressive strength and thermal conductivity. Quartz sand, lime and/or cement as the binder, gypsum and/or anhydrite (depending on the mix formulation) and water are required for its production. The building material acquires its characteristic porous structure through the addition of aluminium powder, which reacts in the aqueous alkaline environment with the evolution of hydrogen and foams the raw mix. AAC only obtains its final properties through hydrothermal treatment in an autoclave, known as hardening.

AAC contains no combustible constituents and is therefore suitable for producing components for all fire resistance classes. However, a phenomenological change in the building material occurs under the influence of rising temperatures. In the test programme described below, AAC was investigated with respect to thermally induced changes in microstructure and their effects on the material properties in the temperature range from 20 °C to 900 °C. This was used as the basis for considering not only the possibility of thermally induced strength optimization but also aspects of re-use.

Investigations into the material properties of AAC in the temperature range from 20 °C to 1000 °C have been published by Schneider et al. [1, 2]. Strength investigations carried out on AAC samples, which before the test had been submitted to different external temperature regimes, showed that pre-treatment temperatures of up to 450 °C produce an increase in compressive strength by a maximum of 85 % relative to the reference compressive strength at 20 °C. It was also observed that at about 700 °C AAC returns to its reference compressive strength at 20 °C and only loses strength significantly if there is a further increase in temperature. The increase in strength was attributed to the drying of the sample, to the loss of crystal water above 190 °C that leads to the formation of additional tobermorite, and to the “consolidation” of the sample that accompanies the shrinkage of the AAC material. The drop in compressive strength above about 700 °C is interpreted as a consequence of the conversion of tobermorite to b-wollastonite that takes place at about 840 °C, coupled with severe shrinkage of the AAC test piece.

Common to the dilatometric measurements on AAC [1-3] that have been published so far is the finding that there is slight shrinkage up to temperatures of 700 °C to 800 °C followed by severe shrinkage up to about 850 °C. The strong tendency to shrinkage caused by reversible adsorption of water and incorporation as interlayer water is characteristic of the less well crystallized tobermorite phases [3, 4].

The current understanding of the thermal behaviour of hydrothermally formed CSH phases is summarized in, among others, [4-6]. Hydrothermally formed calcium silicate phases release their chemically combined water in two stages during thermal treatment, i.e. in the range from 100 °C to 300 °C and between 300 °C and 800 °C. The formation of b-wollastonite takes place in an exothermic reaction at temperatures around 800 °C [7, 8].

11 Å tobermorite, the main bonding phase in AAC, loses the water stored in the interlayers of the crystal lattice at temperatures between 100 °C and 300 °C. With the normal 11 Å tobermorite the associated lattice contraction leads to the formation of 9 Å tobermorite, but no reduction of the basal spacing to 9 Å was detected with the anomalous 11 Å tobermorite [9, 10].

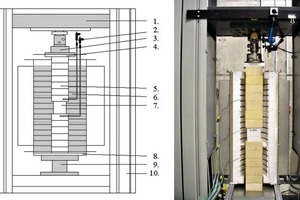

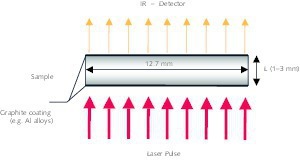

Samples of the currently most widely used types of AAC, namely P2-0.35 (2.5 N/mm2; 0.35 kg/dm3), P2-0.4 (2.5 N/mm2; 0.4 kg/dm3) and P4-0.5 (5 N/mm2; 0.5 kg/dm3), were used for determining the mechanical properties of AAC under the influence of temperature. The test cubes used here with edge lengths of ≥100 mm were conditioned to an equilibrium moisture content of 6 %. A Z 400 test machine from Zwick with integral three-zone kiln (Fig. 1) was available for carrying out the investigations. Three types of test were carried out with the test equipment shown.

s-e diagrams were recorded on AAC block samples that had been previously subjected to stressing in the test equipment. The temperature was first raised to the particular preselected temperature stage (250 °C, 350 °C, 650 °C, 750 °C, 850 °C) at a heating rate of 2 K/min and then held there for a period of 120 min before the load-deformation curve was recorded.

The rate of load increase used for the loading test was 2 % per second of the average failure stress measured at 20 °C. A constant load of 2 kN had to be applied over the entire temperature control period for accurate adjustment of the displacement transducer on the test piece.

The unconfined thermal contraction (eth) of unloaded AAC block test pieces was measured in the vertical direction in the temperature range of 20 °C to 900 °C with the aid of displacement transducers.

Hot-creep tests were used to determine the strain under compression (ew) of the corresponding AAC block material. After it had been installed, the test specimen was heated dynamically at 2 K/min under constant load until failure. The preselected loads corresponded to 25 %, 50 % and 75 % of the reference failure stress at 20 °C. The deformation of the test specimen caused by the loading or temperature change was measured in the vertical direction by quartz glass rods from outside the kiln zone using inductive displacement transducers. The load was introduced into the kiln through fireclay bodies (Fig. 1).

A CAMBRIDGE S 200 scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis spectrometer, a SIEMENS AXS D500 X-ray diffractometer and a METTLER-TOLEDO SDTA 851 thermobalance were available for characterizing the thermally induced changes in microstructure. The sample material was dried at 60 °C, mechanically comminuted and sieved. The 0/0.063 mm size fraction was used for the thermal treatment. Wet-chemistry examination of the powder samples showed a proportion of HCl-soluble constituents of over 75 %, a CaCO3 content of about 10 % and an SO3 content of 3 %. The scanning electron microscope examinations were carried out on AAC fracture surfaces produced after the respective thermal treatment.

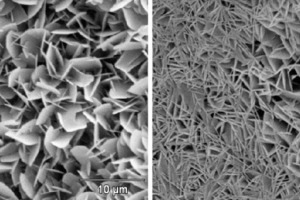

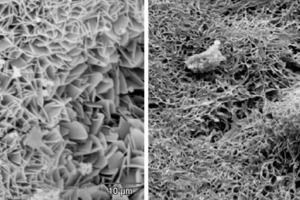

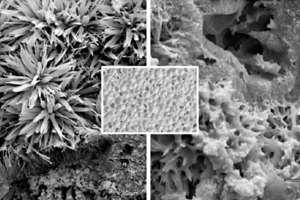

Figure 2 shows examples of two scanning electron photomicrographs of the bonding phase of one of the AAC batches under investigation (P2-0.35). As a rule the bonding phase in hydrothermally hardened building materials consists of tobermorite, which occurs with widely differing morphology depending on the hardening conditions of temperature, pressure and hardening time. In this case the tobermorite is present predominantly in the house-of-cards structure that is beneficial for the working properties.

The phase constitution of the AAC batch was analyzed first by X-ray diffractometry (XRD). In addition to the main 11 Å tobermorite bonding phase not only calcite and residual quartz but also anhydrite and gypsum were detected, which agreed with the SO3 content determined by wet chemistry. The portlandite that is normally present in this material system could only be detected in traces.

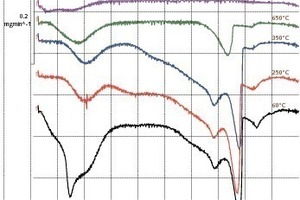

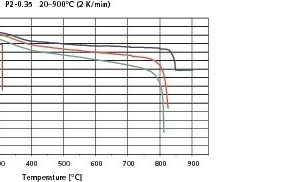

Initial findings about the change in phase constitution with temperature were then obtained from the thermoanalytical investigations (Fig. 3). The DTG curve of the AAC sample that had been pretreated at 60 °C (Fig. 3, bottom) shows particularly conspicuous losses of weight in the temperature ranges 30-300 °C, 650-720 °C and around 850 °C. These can be assigned to the effects described below:

Desorption of the water that is physically and chemically bound at varying strength levels occurs in the 30-300 °C temperature range. Physically sorbed water evaporates up to about 120 °C, 11 Å tobermorite loses water from its interlayers in the 100-300 °C range with the formation of 9 Å tobermorite, and gypsum is converted into hemihydrate between 150 °C and 160 °C and then into anhydrite at about 200 °C. Any portlandite present decomposes in the temperature interval 450-550 °C with the formation of calcium oxide and water.

Decomposition of the calcium silicate hydrate bonding phases occurs between 650 °C and 720 ° C, accompanied by calcination of the calcite up to about 800 °C. The peak with a maximum at about 850° C points to the decomposition of any CSH phases that are still present or have been produced by previous decomposition reactions. An exothermic DTA signal, also at 850 °C, obtained from the results of DTA investigations on the same AAC batch shows that the monophase wollastonite is formed.

Those temperatures that are principally responsible for thermally induced changes in the microstructure of AAC were selected for the following investigations on the basis of the preliminary thermoanalytical investigations. During the course of the subsequent investigations at 250 °C, 350 °C, 650 °C, 750 °C and 850 °C both powder samples and pieces of AAC were thermally stressed for a period of 120 min and then examined in detail by the above-mentioned methods of instrumental analysis.

Figure 3 shows the DTG curves of the P2-0.35 AAC batch recorded after the respective preceding temperature treatments. The DTG curves of the samples treated at 250 °C and 350 °C are similar. In contrast to the sample pretreated at 60 °C the physically sorbed water has already desorbed. However, it is clear that a holding time of 120 min is apparently not sufficient even at 350 °C to convert 11 Å tobermorite into 9 Å tobermorite or convert hemihydrate completely into anhydrite.

The corresponding DTG curve shows that incomplete decomposition of the calcium silicate hydrate bonding phase and also partial decomposition of the calcite occur during the thermal treatment at 650 °C. Desorption of the physically sorbed water as a consequence of the CSH phase decomposition and sorption of the water on the internal surfaces of the AAC samples under investigation were also observed.

Decomposition reactions could no longer be detected at and above a pretreatment temperature of 750 °C, and from 850 °C there was also no H2O desorption to be observed in the range 50-200° C. X-ray diffractograms of the samples held at temperatures of up to 350° C showed that, with otherwise identical diffractograms, the dewatering of 11 Å tobermorite to

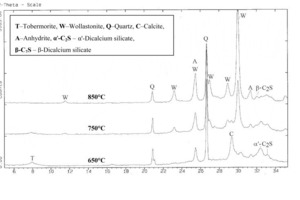

9 Å tobermorite only exhibited a peak drift of about 0.2 ° 2q in conjunction with slight line broadening, which indicated a decrease in the crystallinity of the resulting CSH phases. The conversion of gypsum via hemihydrate to anhydrite was also observed. Figure 4 shows that complete decomposition of the tobermorite phase with simultaneous formation of fresh dicalcium silicate and wollastonite was detected in the temperature range from 650 °C to 850 °C.

The initial formation of a‘-dicalcium silicate from existing CSH phases starts below 650 °C. The change of modification from a‘-dicalcium silicate (a‘-C2S) to b-dicalcium silicate (b‑C2S) and decomposition of all the C2S can be observed above about 750 °C. At the same time, fresh formation of the monophase b‑wollastonite was also detected at about 750 °C. The crystallinity and content of b-wollastonite increased steadily with rising temperature up to 850 °C. Another effect that is clearly visible from the diffractograms is the calcination of calcite (cf. Fig. 4: diffractograms at 650 °C and 750 °C).

At the same time as the investigations of the thermally treated powder samples the AAC microstructure of the thermally treated but mechanical undamaged pieces were examined visually by scanning electron microscopy. No significant changes in microstructure, apart from the occurrence of the first microcracks (Fig. 5a), could be detected in the temperature range up to 350 °C. Bending or curling of individual tobermorite platelets and the increased formation and propagation of microcracks due to the advancing dewatering of the bonding phase can be observed up to 650 °C. These effects increase up to temperatures of 850 °C, during which the bonding phase “fuses together” (Fig. 5b) as the decomposition progresses.

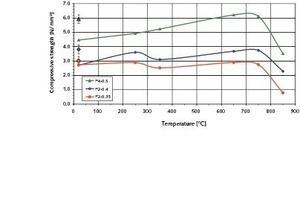

Table 1 contains a summary of the load deformation tests on the three types of AAC examined in the form of the mean values of the measured compressive strengths and contractions at the corresponding test temperatures. Up to 750 °C all three types of AAC exhibited an increase in contraction until failure and a significant drop in strength and contraction at 850 °C (Table 1). With P2-0.35 there was little change in the strength level up to 750 °C but a substantial increase in strength from 20 °C to 750 °C was found with the two other types of AAC. A small, but significant, drop in strength just at 350 °C was observed with both the P2‑0.35 and P2-0.4 AAC.

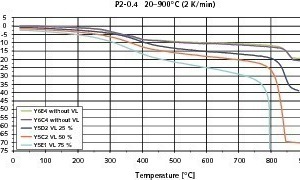

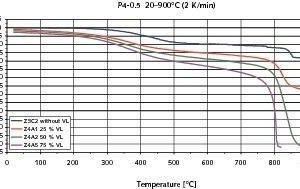

Figs. 6–8 show the results of the contraction measurements on the three types of AAC blocks examined in the form of temperature/contraction diagrams. The reference failure stresses at 20 °C on which the preselected loads are based were 2.8 N/mm2 for P2-0.35, 2.7 N/mm2 for P2-0.4 and 4.5 N/mm2 for P4-0.5. All curves exhibit the increase in compression up to the failure of the AAC test piece.

Regardless of the chosen imposed load the change in length of the test piece is comparatively slight up to a temperature of about 200 °C. This range is adjacent to a temperature interval from about 200 °C to 400 °C with relative large compression. P2-0.35 AAC test pieces that at the start of the measurement had been loaded at 2.1 N/mm2 (75 % preload) had already failed within this temperature range (Fig. 6). Above 400 °C the recorded compression is once again comparatively slight, but increases more strongly with greater preloading and rises rapidly again in the range of the failure temperature. Failure of the test pieces of the AACs under investigation was observed between 760 °C and 840 °C – greater preloading leads to earlier failure.

The results of the thermogravimetric measurements (DTG) showed a continuous loss of weight in the temperature range from 25 °C to 800 °C. The recorded temperature/contraction curves (Figs. 6–8) show that the measured weight loss is associated with compression of the test piece. The temperature ranges associated with comparatively high weight loss and greater compression can be seen from comparison of the DTG curves (Fig. 3) and contraction curves. However, the temperatures of these effects do not match exactly because of the use of test materials that have been prepared in different ways. The displacement of the effect temperatures in the temperature/contraction diagrams when compared with the thermogravimetric measurements is due partly to the less favourable heat transfer in the test cubes and partly to the varying reaction kinetics associated with the changes in microstructure in relation to the desorption and diffusion processes. A temperature shift of about 100 K in the temperature scale of the contraction curves can be assumed on the basis of the temperature measurements of the heat transfer in AAC test cubes.

The first significant change in length of the AAC test pieces in the temperature segment from about 200 °C to 450° C (Figs. 6–8) is therefore attributable to changes in microstructure that, under optimum reaction conditions, take place in the temperature range between 50 °C and 300 °C. The first reactions to take place in this temperature range are desorption of water that is physically and chemically sorbed at varying strength levels, the transformation of 11 Å into 9 Å tobermorite and the dewatering of gypsum to form anhydrite. With 75 % preloading, the test pieces of the P2-0.35 AAC had already failed in the range of approximately 200-300 °C (Fig. 6). The dynamic temperature regime ultimately led to inhomogeneous temperature distribution in the test piece that in turn determined the course of the reaction zones, so that the above-mentioned changes in the microstructure combined with the stresses that inevitably occurred within the test cube led to failure of the P2-0.35 AAC.

A persistent loss of weight over the entire temperature range was detected by thermogravimetry in the following temperature segment from 300 °C to 600 °C. This was matched by a comparatively slight, but continuous increase in the compression with test pieces under high preloading in the temperature window from about 450 °C to 750 °C – or up to about 850 °C with unloaded AAC test pieces. A greater increase in compression was observed under higher preloading. Immediately after this there was a significant increase in compression leading to failure of the AAC test pieces in same order as the preloads that had been applied. The main cause of the failure was the decomposition of the calcium silicate bonding phases in the range 600-720 °C, with superimposed calcination of the calcite up to about 800 °C (Fig. 3).

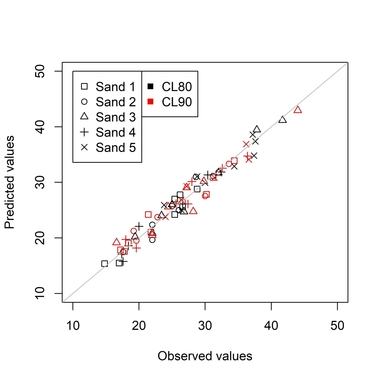

The results of the load-deformation tests carried out in this connection on the three types of AAC investigated confirmed the sometimes significant increase in compressive strength with rising temperature that is also mentioned in [1, 2]. The results that were obtained are summarized in Figure 9.

The compressive strengths of all three types of AAC increased from 20 °C to the temperature range from 650 °C to 750 °C (Fig. 9). With the P4-0.5 AAC the compressive strength increased continuously. However, with the other two types with lower densities there was a slight drop in compressive strength at 350 °C. This increased again with rising temperatures. The drop in compressive strength of the P2-0.35 and P2-0.4 AACs in the temperature range around 350 °C is associated with significant compression of the AAC material as the direct consequence of the changes in microstructure that take place at those temperatures. The compression of the two lighter types of AAC that was measured in the temperature window from 250 °C to 350 °C is about double that of the compression of the P4-0.5 AAC, as can be seen from the uppermost curves in Figs. 6–8.

It should be recorded that under steady-state conditions the changes in microstructure in the AAC below the temperatures that lead to decomposition of the CSH bonding phases contribute predominantly to the stabilization of the AAC. However, it is well known that the compressive strength of AAC is very heavily dependent on its material moisture content. AAC has its highest compressive strength in the kiln-dry state. Material moisture levels around 10 mass % cause a loss of compressive strength of 40 % to 70 %, but higher material moisture levels have only a slight effect on the compressive strength [15, 16]. Test cubes were dried to constant weight at 105 °C without any preloading and their compressive strengths were then measured at 20 °C so that the influence of moisture content on the compressive strength could be estimated for the three types of AAC under investigation. The average results for all three types of AAC are shown in Figure 9 as single values at 20 °C.

By drying the test pieces to constant weight the compressive strengths were increased significantly compared with the samples conditioned to a material moisture content of 6 %. On average, the rise in compressive strength was 16 % for P2-0.35, 27 % for P2-0.4 and 23 % for P4-0.5. Surprisingly, the average compressive strengths of the samples of all three types of AAC dried at 105 °C were approximately the same as the compressive strengths measured in the temperature range from 650-750° C (Fig. 9).

It is apparent that both types of thermal treatment lead to an increase in compressive strength, and the thermal treatment that goes beyond kiln drying does not bring any significant gain in compressive strength. The drying at 105 °C to constant weight causes a loss of the predominantly physically sorbed water, but chemically sorbed water is also desorbed at temperatures just below the decomposition temperature of the CSH phases, which is associated with a compression of the test pieces by about 10-12 mm/m. If this effect of thermally induced increase in strength is to be utilized then it would be necessary to ensure that the reverse reactions to be expected under the influence of moisture do not lead to destruction of the AAC material.

The decomposition of the tobermorite phase was investigated by x-ray diffraction (XRD) in the temperature range from 650 °C to 850 °C. It was established that the following decomposition products were formed as a function of the temperature:

9 Å tobermorite → a‘-dicalcium silicate → b-dicalcium silicate → b-wollastonite

The formation of a‘-dicalcium silicate in this temperature segment was already known from investigations into the thermal treatment of cement-based building materials [11-13, 17]. The fact that the a modifications of the C2S exhibit hydraulic properties that are far more reactive than those of the b-dicalcium silicate phase known from industrial Portland cement clinker deserves special mention [5, 14].

Interesting aspects of the re-use of crushed AAC may possibly arise from the formation of a modifications of the C2S as a result of thermal treatment at relatively low temperatures, especially as the content of CSH bonding phases in AAC is comparatively high due to the nature of the technology.

Financial support from the BMBF for project FKZ 1717X05 and material supplies by the Bundesverband Porenbetonindustrie e.V. are gratefully acknowledged.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.