About the sulfate resistance of slag composites

In Europe it is generally accepted that more than 65 % of granulated blast-furnace slag (GBFS) in composite cements make them high sulfate resistant. Proven by numerous studies, this rule has been implemented into national standards, such as the German DIN 1045-2. Due to the mechanism of sulfate attack, the composition of both, Portland clinker and GBFS influence the sulfate resistance of their composites, apart from an adequate cement and concrete design. In this study, mortars containing GBFS of different composition and high C3 A Portland cement were lab-tested for sulfate resistance. The results illustrate the influence of the alumina content of the GBFS, coupled with its reactivity, on expansion under sulfate attack. A GBFS Sulfate Expansion Index (GSEI) is proposed for rough indication, if a GBFS of given quality would need special attention when used in high sulfate resistant cements. Furthermore it was shown, that Ca-sulfate additions are very effective to increase the sulfate resistance of medium to high alumina GBFS-Portland composites.

1 Background

When sulfates in dissolved form, such as sodium, potassium, magnesium or calcium sulfates from soil or groundwater, enter hardened concrete, they react with the hydrated cement paste. Attacking alkali sulfates react with portlandite to calcium sulfate and sodium hydroxide. In the presence of calcium aluminate, the calcium sulfate reacts to ettringite. This reaction is coupled with a volume increase and pressure buildup, which can result in concrete cracking. According to Kunther (2012), sulfate expansion occurs when first, the pore solution is supersaturated with respect to...

1 Background

When sulfates in dissolved form, such as sodium, potassium, magnesium or calcium sulfates from soil or groundwater, enter hardened concrete, they react with the hydrated cement paste. Attacking alkali sulfates react with portlandite to calcium sulfate and sodium hydroxide. In the presence of calcium aluminate, the calcium sulfate reacts to ettringite. This reaction is coupled with a volume increase and pressure buildup, which can result in concrete cracking. According to Kunther (2012), sulfate expansion occurs when first, the pore solution is supersaturated with respect to ettringite and when second, the ettringite crystals grow under confined conditions, for instance within the microstructure of C-S-H. Then they exert a crystallization pressure, which results in expansion. The attack by magnesium sulfate is even more severe, because it also reacts with calcium silicate hydrates, on top of portlandite and calcium aluminate hydrates, and leads to a softening of the concrete.

The addition of Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag (GGBFS) to OPC in amounts of 50 % and above generally improves sulfate resistance. High sulfate resistance is typically obtained at GGBFS contents of 65 % and higher – provided that the chemical composition of clinker (C3A) and slag (especially alumina), the sulfate content of the system, and the concrete design, including cement and water content, are adequate. As for the mechanism, on one hand the added GGBFS dilutes the amount of calcium aluminates of the clinker.

Secondly, the type and amounts of hydration products differ, and with it their ability to incorporate aluminium, so that, in the long term, less ettringite or monosulfoaluminates are formed, compared to OPC concrete (Richardson and Groves, 1993; Wassing, 2003; Escalante-Garcia and Sharp, 2004; Kocaba, 2009; Taylor et al, 2010; Lothenbach et al, 2011).

Thirdly, the microstructure of hydrated slag cement concrete is denser, compared to OPC concrete. The pores are refined and thus, the penetration of harmful substances into the hardened concrete is physically reduced. Summarizing, the sulfate resistance of slag cement concrete depends on the C3A content of the clinker, alumina content of the GGBFS, the percentage of GGBFS of the total cementitious content, and the water/binder ratio, which determines concrete permeability (Locher, 1966, Frearson, 1967, ACI 1995, Higgins and Uren, 1991, Frearson and Higgins, 1992).

Locher (1966) studied the sulfate resistance of blended cements with GGBFS contents ranging from 5 to 85 %. He used three clinkers with 0, 8, and 11 % C3 A and two GGBFSs with 11 % and 17.7 % alumina. Mortar bars were exposed to 4.4 % Na2SO4. As a result, all composites, which contained at least 65 % slag had high sulfate resistance – provided that the components OPC and GGBFS had a sufficient fineness. These and related findings are reflected in the German DIN 1164-10, where cements with a GGBFS content >65 % (CEM III/B and CEM III/C) are per se declared high sulfate resistant (HS). However, the results of Locher (1966) also show that the sulfate resistance of coarse composites of 11 % C3 A clinker and GGBFS, both at 3000 cm2/g Blaine, depends on the alumina content of the GGBFS. While the coarse composite of 11 % alumina GBFS became sulfate resistant at >60 % GGBFS, the composite with 17.7 % alumina GGBFS at no replacement level achieved sulfate resistance.

Our own unpublished investigations showed, that composites with 50 % GGBFS of 4500 cm2/g Blaine and with 7 to 15 % alumina plus 50 % OPC with 10 % C3 A were sulfate resistant when tested according to ASTM C 1012 with Na-sulfate solution. The expansion of an OPC with 1 % C3 A was reduced when blended with 50 % of 7 and 10 % alumina GGBFS, but slightly increased when blended with 50 % of a GGBFS with 15 % alumina.

Van Aardt and Visser (1967) tested the sulfate resistance of mortars with 30 to 70 % GBFS with alumina contents of 10.1 % and 18.4 % at w/b of 0.45. Under Na2SO4 and MgSO4 attack the 10.1 % alumina GBFS composites performed better at increasing replacement levels than the OPC, which contained 6.6 % and 6.8 % C3 A. However, additions of high alumina GGBFS, reduced the sulfate resistance of the OPC. Also when combined with a C3A-free cement the high alumina GGBFS resulted in an increased expansion.

Osborne (1989) investigated five GGBFS with alumina from 7.5 to 14.7 %, which were combined up to 70 wt-% with cements with 0.6 to 14.1 % C3 A. In mortars exposed to 4.4 % Na2SO4, GGBFS additions improved the performance of the 8.8 and 14.1 % C3 A cements, but reduced sulfate resistance of the 0.6 % C3 A cement. The performance of the 7.5 % alumina GGBFS was excellent, already at 60 wt-% GBFS content. For 9.3 % and 14.7 % alumina GGBFS composites a 70 wt-% replacement was necessary to obtain high sulfate resistance.

Osborne (1991) studied the performance of the same GGBFS and replacements in concrete cubes exposed to either Na2SO4 or MgSO4 for five years. All GBFS composites performed well in terms of retained compressive strength – except the 14.7 % alumina GGBFS composites with 60 or 70 % GGBFS content. In contact with Na2SO4 solution they lost almost all strength.

Higgins and Crammond (2002) investigated how cement type, aggregate type and curing affect the sensitivity of concrete to the thaumasite form of sulfate attack (TSA). They combined 30 % Portland cement (PC) or sulfate-resisting Portland cement (SRPC) with 70 % GGBFS. These cements were combined with various carbonate aggregates or a non-carbonate control. Initial curing was done either in water or air. Concrete cubes were immersed in four concentrations of sulfate solution at 5 °C and 20 °C for up to 6 years. In GGBFS/OPC concretes made with flint aggregates, the GGBFS of high alumina content showed an increased susceptibility to conventional sulfate attack, compared with the normal alumina GGBFS, but was not more susceptible to the thaumasite form of sulfate attack.

Results of that kind have resulted locally in limitations of the alumina content in GGBFS for high sulfate resistance applications – with or without a combination with the C3 A content of the OPC. Thus, BS 8500:2 (2006) states, that when the alumina content of the GBFS exceeds 14 %, the C3 A content of the Portland cement fraction should not exceed 10 % when the cement or GGBFS composite should have sulfate-resisting properties.

The American ACI (1995) prescribes, that sulfate resistant slag concrete should contain at least 50 wt-% of GGBFS in the cementitious, and the C3 A content of the OPC can range up to 12 wt-% as long as the Al2O3 content in the GGBFS is lower than 11 % – an alumina content, which is typically met by North American GBFS. The Austrian öNorm B3309 defines in the chemical requirements for GBFS an alumina content of 9 to 17 %, and the Australian AS 3582.2 listed max. 18 % alumina in GGBFS . In Middle East countries such as Abu Dhabi and Qatar, the market, i.e. specifiers, contractors, engineers, require a max of 14 to 15 % alumina in the commercial GGBFS.

Last but not least, there are ways to improve sulfate resistance when using high alumina slags. Gollop and Taylor (1996) have shown that Ca-sulfate additions have a beneficial effect on the sulfate resistance of blends with high alumina GGBFS. With sufficient Ca-sulfate available, ettringite forms in the plastic state and would not or hardly convert into monosulfate. The latter is deleterious under sulfate attack, because it would react with sulfate ions to ettringite. Coupled with a volume increase, this reaction leads to cracking of the hardened concrete. The beneficial effect of sulfate additions to sulfate resistance of high alumina GBFS composites was confirmed by others, for example Higgins (2003) and Ogawa et al. (2012). On top, but not as stand-alone measure, minor limestone additions <5 % may help to further increase sulfate resistance. Due to their filler effect they densify the microstructure and may bind, at least for some time, some alumina in monocarboaluminate (Higgins, 2003).

2 Objectives

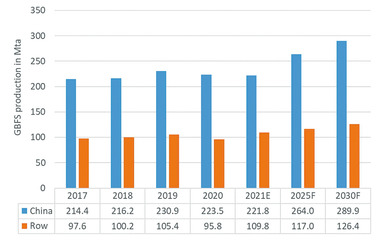

Holcim processes yearly more than 7 Mio. t of GBFS worldwide for the production of composite cements and concrete additions. In the context of steadily increasing requirements on concrete service life, especially in large construction and infrastructure projects, concrete durability aspects, including resistance to sulfate attack, become increasingly required. As the composition of the GBFS varies widely around the globe, mainly due to the different composition of the iron ores used in the blast furnace process, a clear understanding about the influence of the GBFS and clinker composition, along with concrete design parameters and of the effectiveness of mitigating measures has to be established.

Proceeding from the state of the art listed above and considering the possibility that also 65 % GGBFS composites can fail in standard mortar tests such as ASTM C 1012, the influence of the alumina content in GGBFS on sulfate resistance as well as the effectiveness of mitigating measures should be studied in a more systematic way, including a wide range of GGBFS qualities used by Holcim companies. The alumina contents of these slags range from 9 to 19 %.

3 Materials and methods

This paper presents the results of sulfate resistance testing of 50 % and 68 % GBFS composites using a modified ASTM C 1012 approach. The mortars were prepared in accordance to ASTM C 109 and contained 1375 g US standard sand and 500 g binder. In order to accelerate sulfate expansion, the water/cement ratio (w/c) of the ASTM mortars was adjusted at 0.54, deviating from ASTM C 1012. This resulted in a flow of the mortars of 110 +/-5 %. Consequently, the limits given in ASTM C 1157 for sulfate expansion at 182 and 365 days do not apply.

The chemical and mineralogical composition of the OPC and the GGBFS used are given in Table 1.

An OPC high in C3 A was selected, which would exceed the 10 % C3 A limit required by BS 8500:2 in case GGBFS with >14 % alumina would be used in high sulfate resistant products. The alumina content of the five GBFS ranged from 9.3 to 19.3 %. Due to these differences in alumina, basicity and fineness, the reactivity of these ground GBFS (GGBFS) materials differed significantly.

14 composite cements were produced by blending the OPC with one of the five GGBFS, with and without addition of Ca-sulfate. Ten composites contained 66 to 68 % of GGBFS and thus represent CEM III/B cements according to the European EN 197-1. According to some national standards such as DIN 1164-10, these CEM III/B cements would be high sulfate resistant. BS 8500:2 would declare the composites with GBFS 1 and 2 high sulfate resistant, but not the composites with GBFS 3, 4 and 5 (Tab. 2).

Four composites (9, 10, 13, 14) would be CEM III/A cements, according to EN 197-1. They were included to investigate sulfate resisting properties when only 50 % of GGBFS are added, according to the advice of ACI (1995), which nota bene is given for the North American, low alumina slags. Also here, half of the mixes contain Ca-sulfate additions. The Ca-sulfate dosage was in every case adjusted in order to achieve 3.8 % SO3 in the resulting cement.

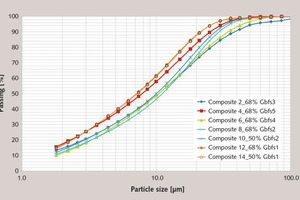

The fineness indicators (Tab. 3) show that the OPC and GBFS 1 had a comparable PSD and fineness, and GBFS 5 comes close to that. Thus, the PSD curves of the composites 12 and 14 are almost identical and the PSD of composite 4 comes rather close (Fig. 1). GBFS 2, 3 and 4 are coarser with GBFS 3 having a rather broad PSD, which is reflected by the PSD of composite 2 (Fig. 1).

4 Results and discussion

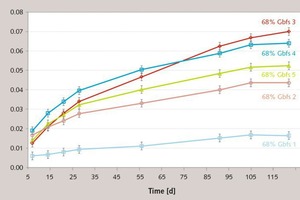

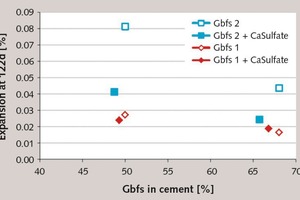

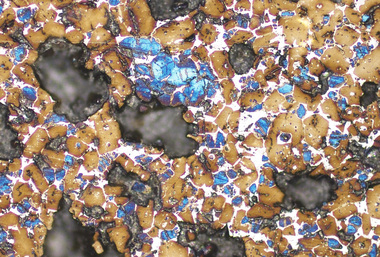

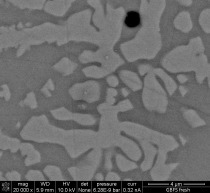

The expansion of the mortars with 68 % GGBFS32 % OPC composites under sulfate attack differs clearly (Fig. 2). The alumina content of the GBFS seems to be a dominating parameter, but obviously not the only one. The mortar with GBFS 1, which had the lowest alumina content, had the lowest expansion. Here, apart from the low alumina content of the slag, also the higher fineness supported the formation of a dense microstructure, which also physically reduced the ingress of sulfate.

The second highest expansion showed the mortar with GBFS 2, which had the second lowest alumina content of 11.2 %. Then the order of expansion deviates from the alumina content of the GBFS.

Next is the mortar with composite 5, which contains the GBFS with the highest alumina content of 19.3 %. However, this cement, like also composite 1, has a significantly higher fineness (Tab. 3). This leads to a higher reaction rate and thus to a faster refinement of the microstructure and incorporation of alumina in the C-S-H.

The faster hydration progress is confirmed by the extraordinary strength development of the mortar with GBFS 5 (Fig. 3). Looking at the sequence at 55 days, the composite with GBFS 3 (14.6 % alumina) would follow and finally that with GBFS 4 (18.7 % alumina).

However, at ~75 days the expansion of the mortar with GBFS 3 surpasses that of the mortar with GBFS 4. Considering, that GBFS 2, 3 and 4 have a comparable fineness, clearly the reactivity and with it the degree of reaction of the GBFS plays an important role for sulfate expansion. Among GBFS 2, 3 and 4, GBFS 3 has the highest reactivity, which is also reflected by its superior mortar compressive strength development (Fig. 3).

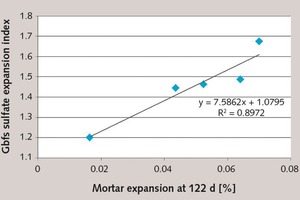

As sulfate expansion appears to be linked to both alumina content and general reactivity of the GBFS, a “GBFS Sulfate Expansion Index” or GSEI was defined for rough prediction of the susceptibility of a GBFS to expand during sulfate attack under given lab testing conditions. Included are CaO, SiO2 and Al2O3 contents of the GBFS as well as its glass content.

(CaO + Al2O3) Glass content

GSEI = ∙

SiO2 100%

The GSEI correlates reasonably well with the sulfate mortar expansion observed at 122 days (Fig. 4). Based on this data set, the GSEI gives a rough indication, if a GBFS of a given quality would need special attention when used in high sulfate resistant cements, for instance regarding optimization of sulfate content or particle size distribution. The usefulness and robustness of the GSEI index has to be confirmed by additional and longer term tests and by using other test methods.

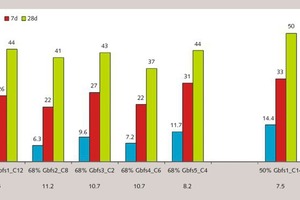

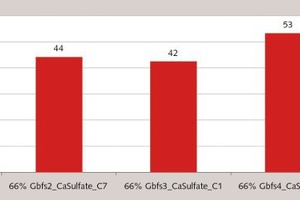

For mortars with 68 % of GBFS 2, 3, 4, or 5, the addition of Ca-sulfate decreased sulfate expansion significantly by over 40 % (Fig. 5). It may be assumed, that a sufficient sulfate supply favours the formation of ettringite over the potentially deleterious monosulfate.

For the low alumina GBFS 1 composite, which had the lowest expansion, the Ca-sulfate addition had no such effect. For the composites with GBFS 2 and 3 with 11.2 and 14.6 % alumina respectively, Ca-sulfate additions reduced sulfate expansion at 122 days by 42 to 44 %. An especially high reduction of sulfate expansion by over 50 % was achieved for the high alumina GBFS 4 and 5 composites, when Ca-sulfate was added.

The higher the GBFS content in the total cementitious phase, the better is the sulfate resistance (Fig. 6). Our results show that the expansion of the mortar with 50 % of GBFS 2 in the cement plus Ca-sulfate addition after 122 days was similar to that of the 68 % composite of GBFS 2 without Ca-sulfate addition. This implies that Ca-sulfate additions might allow for a certain reduction of GBFS content in sulfate resistant cements. This however needs to be supported by further studies.

Clearly, the impact of elevated GBFS contents, usually >65 %, on sulfate resistance is based on the refinement of the microstructure by higher amounts of C-S-H and by the different hydrate assemblage, which forms in hydrated GBFS composites compared to OPC. Apart from incorporation into ettringite and monosulfate, in hydrated slag cements alumina is also consumed for the formation of a hydrotalcite-like phase and is incorporated in the C-S-H structure. Thus, hydrated GBFS composites at long term contain less ettringite and monosulfates than hydrated OPC, even though the total alumina content of the unhydrated slag composites was higher than that of pure OPC (Richardson and Groves, 1993; Wassing 2003, Escalante-Garcia and Sharp, 2004; Kocaba, 2009; Taylor et al, 2010, Lothenbach, 2011). As, in addition to the lower amount of available alumina, also the portlandite content of slag concrete is significantly lower than in OPC concrete due to dilution of the Portland clinker by major GGBFS additions and by some portlandite consumption during slag hydration, high slag cements are less vulnerable to sulfate attack. Last but not least, the denser microstructure of slag cement concrete due to pore refinement by the high amounts of C-S-H provides a physical entrance barrier for aggressive solutions.

In practice sulfate attack in natural environments is far less severe than under lab conditions. Only less than 1% of damages of reinforced concrete can be related to sulfate attack. Reasons are the use of adequate concrete designs and lower sulfate concentrations in the field, but also the presence of different cations and of bicarbonate ions, which reduce the sulfate uptake into C-S-H, destabilize ettringite and thus reduce sulfate expansion of slag cement mortars (Kunther, 2012). This is in line with the beneficial effect of minor carbonate additions on sulfate expansion of slag cement concrete described by Higgins (2003).

5 Conclusions and outlook

The alumina content of GBFS has a significant effect on sulfate expansion of laboratory mortars, but also the reactivity of the GBFS plays an important role. A GBFS Sulfate Expansion Index (GSEI) is proposed, which combines the alumina content with other constituents of GBFS, which dominate its reactivity. The GSEI seems to allow a rough evaluation of the tendency of a given GBFS to expand under sulfate attack under given lab testing conditions, in combination with an OPC. The robustness of the GSEI has to be confirmed by further tests.

Ca-sulfate additions are powerful in reducing sulfate expansion of medium to high alumina GBFS composites. Other factors influencing the sulfate resistance are the C3 A content of the Portland clinker, which in our case was intentionally selected to be elevated, the percentage of GBFS in the total cementitious phase, and the hydration rate of the system, which is determined by the fineness of the constituents, by their intrinsic reactivity and by the total cement reactivity. In this respect also the cement and concrete design parameters are decisive, especially the content of water and cement.

The trend towards performance-based concrete testing takes the importance of the entire concrete design into account. It is obvious, that durability tests on a mortar basis are not sufficient to predict the sulfate resistance of the final product, which is the concrete.

Most mortar tests are done at a water/cement ratio around 0.5. Here, only the cement properties are tested without considering the performance design of the concrete. However in the final application, the concrete design parameters play a crucial role on its long-term performance regarding strength and durability. According to the Swiss standard SN EN 206-1, for example, concrete for underground work for the exposure class XA3 needs to contain a minimum of 360 kg/m³ cement with high sulfate resistance, has to have a w/c of maximum 0.45 and a minimum strength class of C 35/45.

As it is of paramount importance to include the concrete design in the considerations, this study is being complemented with sulfate resistance tests of concrete specimens according to SIA 262/1_Annex D.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.