Unveiling the “invisible”

AFR co-processing limitations

Most cement plants have limitations in terms of co-processing due to flow stratification leading to lower fuel burnout/calcination, high CO/NOx and build-ups. The identification of flow stratification is extremely difficult and requires elaborate in-flame and 3-D mapping of the temperature and major gas species to quantify the air-fuel mixing pattern and mixedness levels. In this paper, a mineral interactive computational fluid dynamics (MI-CFD) model encompassing combustion and mineral interactions is used to visualise intricacies of calciner internal aerodynamics and its effect on meal calcination levels and fuel burnout. Modelling results provide a cost-effective way to reduce flow stratification, which leads to the implementation of low-cost solutions.

1 Introduction

The use of alternative fuels and raw materials have become an undeniable reality in the cement industry worldwide, motivated by ever increasing fuel costs as well as environment-efficient solutions. Under the name “co-processing”, the use of these unconventional materials in the cement manufacturing process with the purpose of energy and/or resource recovery combine the safe disposal of these residues with economic savings of the reduction in the use of conventional fuels and raw materials through substitution. The alternative fuels therefore are regularly “co-processed”, but not...

1 Introduction

The use of alternative fuels and raw materials have become an undeniable reality in the cement industry worldwide, motivated by ever increasing fuel costs as well as environment-efficient solutions. Under the name “co-processing”, the use of these unconventional materials in the cement manufacturing process with the purpose of energy and/or resource recovery combine the safe disposal of these residues with economic savings of the reduction in the use of conventional fuels and raw materials through substitution. The alternative fuels therefore are regularly “co-processed”, but not always in the optimal and cost-effective ways.

Although most plants consider fuels costs the highest single parameter in their production cost and sometimes the specific heat consumption, in terms of MJ/kg of clinker, is the key factor used in order to define the feasibility of a cement plant in some markets, co-processing is far from being globally developed. The average thermal substitution rate in Europe between 2008 and 2012 was about 35 %, and while some countries such as Germany and Austria reported around 60-65 %, other countries like Italy and Ireland were at 10 % and 4 %, respectively. In Latin America, Brazil – one of the biggest producers of cement with more than 80 units – presents an average thermal substitution rate of 9 % [1].

The main reasons for low AFR substitution rates are the operational difficulties or the impact of introducing alternative material on production rates, clinker quality and emissions control, which highly depend on the type of alternative materials available on each local market. Alternative fuels are characterised by a very broad range of physical (i.e., size, shape and density) and chemical properties (i.e., composition and reactivity). Figure 1 shows a number of examples of (a) gross and prepared traditional fuels and (b) alternative solid fuels usually found in cement plants [2].

According to the source and quality, the specific heating value for solid alternative fuels can vary from 3 to 23 MJ/Kg, with a moisture content ranging from 5 to 30 %. Typically, cement plants established some quality control limits like minimum CV of 3000-4000 kcal/Kg, maximum moisture of 10 % and maximum chlorine of 1 %. Since alternative materials are more difficult to handle than conventional fuels, some investment in AFR preparation, storage and handling systems is required to preserve these quality parameters and sustain the co-processing activities.

It is well known from co-processing plants that alternative fuels usually require higher flue gas volumes and a greater volume of combustion air as well as differences on the heat release profile inside the kiln/calciner. There are many suppliers offering new technologies and special designed equipment that can make 100 % alternative fuels TSR successfully achievable, but all of them require significant investments. The aim of this paper, therefore, is to highlight the need of a detailed knowledge on specificities of each equipment/plant in terms of mixing, combustion, emission and calcination within a calciner, produced by a specifically developed MI-CFD in order to assure that any investment in plant improvement will lead to the expected performance.

2 Unveiling the “invisible” AFR co-processing

culprit

For the purposes od this paper, “Flow Stratification” can be defined as inadequate or poor mixing between the combustion gases coming from the kiln with tertiary air and with particle streams of fuel and meal. It means that when flow stratification takes place inside a calciner, the gases rich in oxygen and the lean oxygen gases follow different paths into the calciner exit direction, creating an extremely inhomogeneous oxygen concentration profile along the calciner body.

The consequences of inefficient mixing are very often observed in a cement plant, even for non-co-processing plants. Depending on the level of flow stratification, it includes high level of unburnt carbon in hot meal, increase in the intensity of sulphur cycles, build-ups, high CO and high NOx formation. In short, the flow stratification leads to a very poor combustion because most of the fuel particles will not find the oxygen path, and to a low calcination performance due to slow heating release, combined with inefficient heat transfer to meal particles.

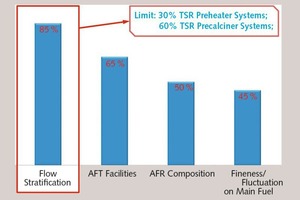

Considering all challenges of alternative fuels usage previously discussed, it is not difficult to see how a poor mixing can limit the co-processing. In fact, the main reason for 85 % of the cements plants being limited to a maximum of 30 % TSR (pre heater systems) and 60 % TSR (precalciner systems) is the flow stratification as shown in Figure 2 [3].

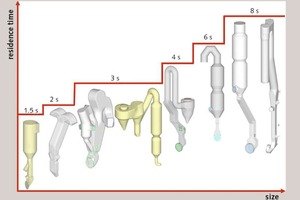

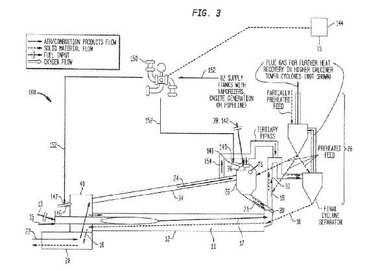

Despite its intensive and direct effect on the calciner performance, the flow stratification is not easily identified by most process engineers. Especially when alternative fuels are being used, it is generally assumed that the consequences of deficient mixing are in fact due to low gas residence time, or that the poor combustion happens because the calciner is too small to burn a larger but unstable alternative fuel feeding. Therefore, in recent years calciners have been built bigger and bigger to allow for higher gas residence time (Fig. 3).

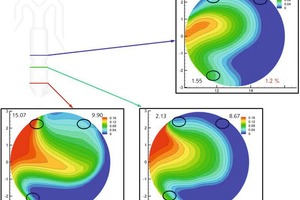

The identification of flow stratification is extremely difficult and requires elaborate in-flame and 3-D mapping of the temperature and major gas species to quantify the air-fuel mixing pattern and mixedness level. However, this can only be achieved if detailed mineral-interactive computational fluid dynamics (MI-CFD) calculations are carried out. The details of the MI-CFD approach and applications are presented elsewhere [4, 5]. Figure 4 shows a typical example of a unique ability of avoiding unnecessary investments.

This happens because detailed measurements on gas compositions and temperature in many different points of the calciner body are mostly very difficult to take and prohibitively expensive. As a result, a process engineer has no means to get a meticulous defined oxygen concentration profile. Collecting gas samples or measuring flow velocities in most locations is further hindered due to the higher particle loading. Hence, during their daily activities the process engineers are usually limited to a few measurement locations from where it is only possible to take a snapshot of global heat and mass balances. In order to illustrate how this traditional practice makes flow stratification an “invisible” problem, we can analyse the example shown in Figure 4.

In this case a careful oxygen measurement campaign was conducted by a process engineer in three points for three different levels of calciner body above the tertiary air and fuel inlets, giving that the average oxygen concentration drops from 12 % to 4.2 % and then 1.2 % while gases flow through the calciner body to the exit. Taking these numbers to a global mass balance, the conclusion was that the available oxygen was being consumed leading to a low exit oxygen concentration and that in order to increase TSR a higher volume of flue gas would be necessary and hence a bigger calciner. Since the measured values and global mass balance showed coherently possible oxygen consumption, the limitation caused by flow stratification in this case could not possibly be detected.

Fortunately, prior to investing in the calciner upgrade, the plant management decided to apply the MI-CFD modelling. The differential numerical calculations performed with MI-CFD showed that the real problem was not the calciner size, but the “invisible” phenomena. The process engineer’s measurements were correct but not detailed enough to identify the core of the problem, which lay in poor mixing of the tertiary air with riser duct gases – the problem of flow stratification. The measurement locations were completely outside of rich oxygen regions.

By using the MI-CFD results, the plant could work on two new possible solutions, either to invest in a tertiary air modification in order to improve the mixing efficiency, or to inject the AFR in rich oxygen regions as shown by the crisp 3-D MI-CFD modelling plots. The latter solution, however, is less expensive and can bring more benefits than the usual calciner upgrade approach – by increasing the calciner dimensions.

3 Effective solution: improving mixing

and fuel/meal injection locations

Once the problem of flow stratification has been identified as a limitation to increase TSR, possible solutions need to be analysed in detail and its cost-benefits comparison well addressed at the design stage to avoid future disappointments.

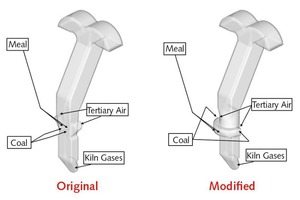

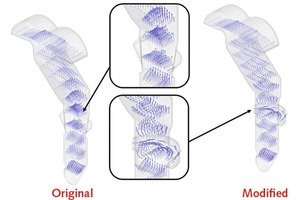

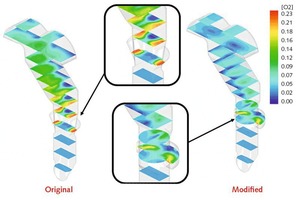

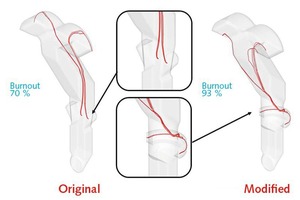

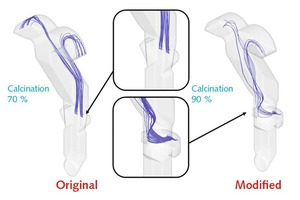

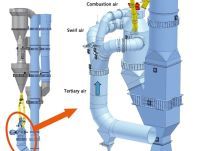

The next example of the application of MI-CFD technique to reducing flow stratification shows how a calciner design (Fig. 5) had been modified and the effects of its modification on flow aerodynamics (Fig. 6), oxygen concentration profile along calciner body (Fig. 7), coal particles trajectories (Fig. 8) and meal particles path (Fig. 9).

In Figure 6 the flow aerodynamics is represented by a total velocity field in vector form for both calciner configurations. It is possible to note that the tertiary air penetration into the main kiln gases flow is much more effective on modified geometry with a horseshoe shaped tertiary air duct (TAD). In this configuration, there is a significant change in vector directions and organisation after the tertiary air level indicating that above it the kiln gases and tertiary air are mixing and flowing uniformly.

The oxygen concentration profile (Fig. 7) shows that while in the original geometry there is a clear stratification with rich oxygen regions (as indicated by red colour) near to the lateral wall where the tertiary air is injected which disappears due to a better mixing promoted by a horseshoe design.

In the original design the coal particles present a poor spreading and travel near to its injection wall towards the calciner exit (Fig. 8). Since coal particles travel in low local oxygen regions, the average burnout achieved is 70 % which is a very low value for a traditional fuel. Besides, the more uniform oxygen concentration is promoted by the TAD modification by replacing the coal burner locations, the more particles are forced to go through a longer path along the calciner centre. An average coal burnout of 93 % is achieved with the horseshoe shaped TAD configuration.

The new meal inlets (Fig. 9) lead to an increasing from 70 % to 90 % on calcination levels by allowing for a better particles’ spread, and forcing meal to go through the calciner centre near to the regions where heat is released by coal combustion. These modifications had been implemented and largely improved the calciner performance and clinker production.

4 Final remarks

The cement industry has significantly reduced its energy costs and has become more environment-efficient using alternative fuels and raw materials. However, the full potential of AFR is not fully explored in the absence of a sufficient understanding of combustion, emission and mineral reaction interactions inside the kiln and the calciner. Most cement plants are limited in terms of co-processing due to flow stratification leading to lower fuel burnout/calcination, high CO/NOx and build ups.

The identification of flow stratification in turbulent reacting flows is extremely difficult and requires elaborate in-flame and 3-D mapping of the temperature and major gas species concentrations. Only by knowing local oxygen concentrations and temperature within the calciner, it is possible to adequate it for optimum performance.

In this paper, detailed mathematical models encompassing combustion and mineral interactions were used to visualise intricacies of the calciner flow and reaction regimes and its effect on meal calcination levels as well as fuel particle burnout. Modelling results provided a cost-effective way to improve the thermal substitution of AFR while making the most out of exiting calciner dimensions, rather than going for unnecessary up-grades.

5 Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration and financial support of our clients as well as their permission to present these MI-CFD specific mathematical modelling results. A special thank you to Naminda Kandamby, Michalis Akritopoulos and Shan Raza for their technical support and collaboration.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.