Rock powder as aggregate

for hydraulic binders

In the extraction and production of high-grade aggregates, the formation of finely dispersed particles is unavoidable. Up until now, these rock powder were only partly or not utilized at all. A research project sponsered by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy and supported by the industry was initiated to evaluate possibilities for using these materials in cements and concretes to utilize their dispersity and/or chemical properties. First, the influence of the particle size distribution on the packing density was investigated and the effects of a particle size distribution modified by grinding and classification were evaluated. The second focus was on reactivity in an alkaline milieu, certain specimens undergoing additional thermal treatment.

1 Current knowledge

The effect of finely dispersed waste and by-products in cements and concretes has been the subject of a large number of studies. In the case of the waste products used as a cement substitute, so far the focus has been on “traditional” industrial by-products such as slag sand, coal fly-ash and microsilica [1-4]. In recent years, the studies have been widened to cover kaolins or clays [5-8]. In the case of these materials, the reactive potentials are first generated by means of thermal treatment so that the materials can then be used as a cement component [9-20]. Other studies...

1 Current knowledge

The effect of finely dispersed waste and by-products in cements and concretes has been the subject of a large number of studies. In the case of the waste products used as a cement substitute, so far the focus has been on “traditional” industrial by-products such as slag sand, coal fly-ash and microsilica [1-4]. In recent years, the studies have been widened to cover kaolins or clays [5-8]. In the case of these materials, the reactive potentials are first generated by means of thermal treatment so that the materials can then be used as a cement component [9-20]. Other studies are related to rocks of volcanic origin such as tuff, pumice or zeolite [21-29], as on account of their genesis and composition these materials can be expected to be suitable as a cement substitute.

The studies described here are directly related to works exploring the use of rock powder in mortars and concretes. Abukersh [30] used a granite dust coming from a comminution process during mineral processing. The dust had an upper particle size of 150 µm. The additive amount was larger than the amount of cement that was saved in the concrete formulation so that parallel to a cement substitution of 19 %, the content of powder grains was increased. The decline in the 28-day strength was small.

Vijayalakshmi [31] used granite powder from grinding and polishing processes with an undersize of 55 % at 150 µm for the production of concrete. The cement content was not reduced. The granite powder was added at the expense of the sand content. For an addition of 25 %, the decline in strength was around 10 %.

Li [32] used granite dust from the removal of filler from crushed sands. The particle size at an undersize of 90 % was 67 µm. The produced concretes contained Portland cement and Portland cement with 10 % slag powder or 30 % fly ash as binder. The fly ash was substituted with the granite powder, a maximum of 30 % binder mix being substituted. A considerable decline in strength was registered.

Laibao [33] tested basalt powder that had been produced as a by-product from comminution and showed a residue of 7.7 % on a 45-µm screen. Up to a cement substitution of 25 %, a linear reduction in strength resulted, which was located above the dilution curve calculated for inert material. Despite this, the powder met all the requirements for a pozzolan specified in ASTM C 618, including the activity index. This is defined as the ratio of the strength of a mortar with 20 % pozzolan to that of a mortar without pozzolan and must be 75 % after 7 and 28 days.

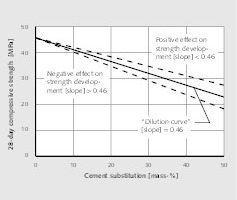

An empirical model for the effect of inert and pozzolanic additives on strength was developed by Cyr, Lawrence and Ringot [34-36]. It is based on studies of quartz and limestone powder as non-pozzolanic additives as well as fly ashes as pozzolanic material. According to this, the cement substitutes can demonstrate three effects:

Inert, coarse substitutes have a “diluting” effect. The resulting decrease in strength is caused by the increase in the water/cement ratio and can be calculated with the help of the law-of-Abrams (cf. [37]).

Inert, fine substitutes act as heterogeneous nucleating agents and lead to an increase in the degree of hydration in the early stage of hydration. This resulted in an increase in strength as opposed to the strength decrease caused by “dilution”.

Pozzolanic substitutes are directly involved in hydration. The increase in strength occurs later and is larger than that achieved with heterogeneous nucleation.

An increase in strength caused by the increase in the packing density could not be proven as neither density nor air content of the mortar prisms with rock powder were changed compared to the reference mortars.

2 Materials tested and experimental methods

For the tests, three diabase powders, one basalt powder, two rhyolite powders and a greywacke powder were used. All seven rock powders come from quarries in Saxony and Thuringia/Germany. The powders consist of extracted filler and were removed from the designated silos. One exception was the basalt, which was available in the size fraction 0 to 2 mm.

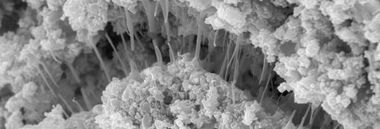

The rock powders were tested in respect of their chemical and mineralogical composition as well as their granulometric parameters. To identify possible variations, multiple samplings were performed in two campaigns. For each location, 14 to 25 individual samples were taken. The chemical composition was determined with the help of X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF) and the loss on ignition at 1025 °C was determined. The mineralogical composition was characterized by means of X-ray diffractometry (XRD). All rock powders were tested in the starting state and selected powders after their thermal treatment. The particle size distribution was measured with a laser granulometer on samples dispersed in isopropanol after 120 seconds of internal ultrasonic treatment. To evaluate the particle shape before and after thermal treatment of the rock powders, SEM images were captured.

For the tests as a cement substitute, material from a single sampling was tested. As reference materials, a cement CEM I 42,5 and a quartz sand were used. To actively influence suitability as a cement substitute, the particle size distribution of some of the powders was modified by means of grinding in a laboratory roller mill. Like the procedure to initiate activity in clays, selected powders underwent a thermal treatment in an electrically heated muffle kiln with a heating rate of 200 K/h and a residence time of 2 hours.

The pozzolanic activity of a cement substitute depends on the chemical reactions of the calcium hydroxide during cement hydration with silicon- and aluminium-rich reactive substitute components. It can therefore be quantified based on the Ca(OH)2 consumption caused by these reactions. In the studies described here, the Chapelle test following the FR standard NF P 18-513 [39] was applied (Figure 1). In this test, the consumption of Ca(OH)2 at a temperature of 85 °C is determined over 16 hours. For this purpose, 250 ml distilled water was added to a weighed amount of 3.5 to 4 g rock powder < 63 µm and 2 g CaO and mixed in a closed vessel with a magnetic stirrer. The Ca(OH)2-consumption is determined at the end of the test by means of titration with 0.1-molar HCl.

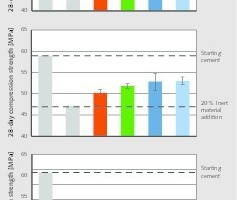

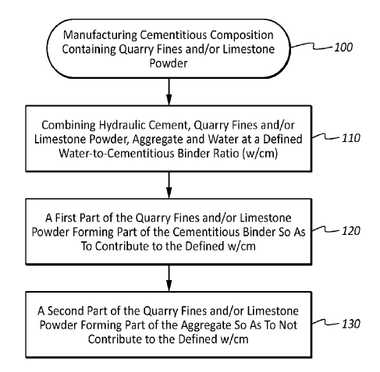

Another characteristic value suitable for the evaluation of the contribution of the powders to hardening is the strength development in cement pastes. To determine this, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mass% of the cement was substituted with rock powder. On account of the low powder quantities in some cases, for the strength tests, 12 prisms of 10 mm x 20 mm x 60 mm had to be used for each rock powder and mixing ratio. For this purpose, in two batches each of 200 g binder – consisting of cement and rock powder – were mixed with 76 g water (water/binder ratio 0.38), mixed for three minutes in a laboratory mixer and then poured into the mould, to be compacted by striking the mould ten times. Stripping and storage were performed in compliance with DIN EN 196-1 [40]. After 28 and 90 days, the dynamic modulus of elasticity and the flexural strength of six prisms in each case were tested. The compressive strength of 12 prism halves in each case was measured. The strengths, determined from the relatively small prisms, are associated with comparatively wide scatters. For this reason, it was first tested whether the measured values attributed to the two prepared batches differ. That was not the case. As the characteristic value for the influence of the rock powders on the strength of the pastes, the effect of the compressive strength on the substitute cement amount was determined. For an inert additive, the following relationship applies:

σ = σ0 · (1 - Subtstitution )

100

where

σ0: compressive strength of the reference cement in MPa

σ: compressive strength of the rock-powder-substituted cements in MPa

Substitution in mass%

Based on the slope of the function σ = (Subtstitution), it is possible to decide whether a contribution is made to strength development or there is a negative effect to strength development (Figure 2).

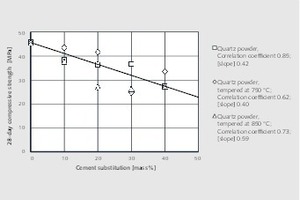

On the basis of quartz powder as an inert additive, the different cases of dependence σ = (Subtstitution) are shown by way of example (Figure 3). With the use of the quartz powder without treatment, the strengths roughly follow the dilution curve with a low tendency to contribute to strength development. After a tempering at 750 °C, the influence on the strength development hardly changes, however, the correlation becomes weaker. From the strengths attributed to the samples tempered at 850 °C, a relationship can be identified. There is a negative influence on the strength.

Based on the results of the cement paste strength measurement, three rock powders were selected for the production of mortar mixes on standard mortar prisms. As the varying parameters, again the substituted amount of cement, the thermal treatment and the granulometry of the rock powder were chosen. For the mortar prisms, prepared based on DIN EN 196 and compacted on a vibrating plate, quartz sand between 0 and 4 mm was used as the coarse aggregate, with less than 1.5 vol% fraction < 63 µm.

3 Characterization of the rock powders

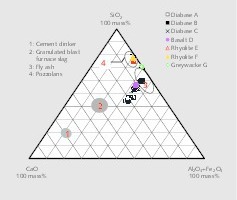

The oxide compositions in Table 1 show the typical differences between the diabases and the basalt as basic rocks and the rhyolites as acid rocks. The coefficient of variation as a measure of the different chemical composition of the weekly samplings are highest for diabase B and lowest for rhyolite E. A first assessment of the effect of the powders in cementitious systems is provided by the three-phase diagram CaO – SiO2 – Al2O3 + Fe2O3 in Figure 4. Of the basic rocks, a pozzolanic effect can only be expected from diabase B. In contrast, the acid rocks including the greywacke are located in the region of the pozzolans so that a participation in the reaction appears possible.

The mineralogical composition of the rock powders (Table 2) shows that a high content of clay minerals in the diabases could be documented. These are almost completely absent from the basalt. It shows a high X-ray amorphous content. In contrast, the rhyolites are rich in quartz and feldspar. The composition measured for the powders does not have to correspond to the mean respective rock composition. As a result of the varying resistances against comminution of the different constituents of the rocks, the content of diverse minerals in the powder can be concentrated and depleted compared to the coarse aggregates. The high content of clay minerals in the diabases could be explained by this.

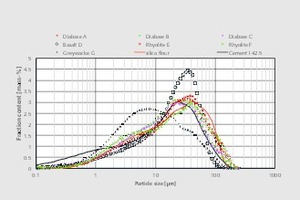

The particle size distributions of the powders were determined in the starting state. An exception is formed by the basalt, which in the starting state existed as sand with an upper particle size of 2 mm and therefore was first ground in a laboratory mill.

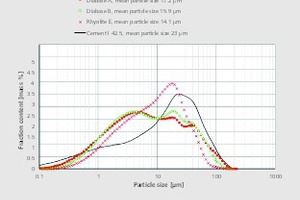

With the exception of the greywacke and basalt, there are small differences between the particle size distributions of the powders (Figure 5). All powders have a maximum particle size of around 200 µm. The mean particle sizes range between 26.2 and 34.3 µm (Table 3). The powder from the greywacke and basalt and the cement are finer. The cement has the highest content in the range of particle sizes up to around 2 µm.

The densities of the rock powders including the quartz powder range from 2.64 to 2.85 g/cm³, which can be attributed to the mineralogical compositions. Their vibrated densities show small differences. However the densities are clearly below that of the quartz powder and the cement.

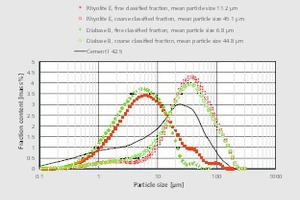

In the particle size distributions, obtained by the additional grinding or the separation in coarse and fine fractions by means of classification (Figures 6 and 7), clear shifts in small particle sizes can be identified. Despite that, the deficit in the area between 0.1 - 0.3 µm compared to cement remains. In the case of the diabase, after additional grinding, a multimodal distribution exists that could be caused by the formation of agglomerates.

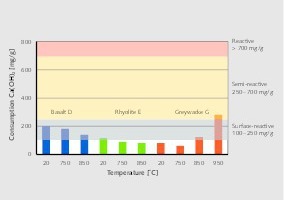

4 Activity of the rock powders

The reactivity of the rock powders in the original state is low (Figure 8). At best, the basalt exhibits a certain surface activity, which can probably be attributed to the amorphous content. The diabase powders are completely inactive like the quartz. With the tempering their reactivities change (Figure 9). For the basalt and the rhyolite E there is a decrease whereas for the greywacke there is an increase in reactivity with increased temperature. However, only for the greywacke is there a relationship between the phase composition and the reactivity. The amorphous content increases with increased temperature during the thermal treatment.

The parameters of the function σ = (Subtstitution), of the compressive strengths of cement paste prisms, are summarized in Table 4. On the basis of the correlation coefficients and the slopes, the first evaluations were performed. For the diabase no participation in the strength development can be proven. After temperature treatment at 750 °C, the basalt and rhyolite E participate in strength development. In the case of the basalt, the tempering causes an agglomeration of the powder. This leads to differences in the participation of hydration, which could be the cause of the comparatively large scatters in the measured strengths. The greywacke is activated by the tempering and participates in strength development. On the basis of this first evaluation, the basalt, rhyolite E and greywacke were selected for further tests.

5 Mortar strengths

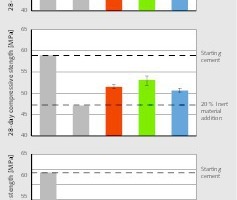

The mortar strengths after 28 days were determined on the starting cement as well as cements with 10, 20 and 40 mass% rock powder. The effects of cement substitution are shown in Figures 10 to 12. For all tested powders, the achieved strengths were not below the calculated dilution curves.

If the basalt powder is used as cement substitute, for the powder tempered at 750 °C, the highest strengths results at all substitute amounts. The clearest differences occur with a substitution of 10 mass% cement with basalt powder. Precondition, however, is that the grain coarsening occurring as a result of thermal treatment can be rectified by means of grinding after tempering. The positive effect of the basalt powder on the mortar strength agree with the results of the Chapelle test and could be related to the X-ray amorphous content of the basalt powder.

Rhyolite powder E shows after additional grinding a participation in strength development. The strength of the mixes of cement and classified fine powder remain at a substitution of 10 and 20 mass% behind the strength of the cements with ground rhyolite. Only with an additive amount of 40 mass% can a difference between the cement with ground rhyolite and the cement with classified fine powder be registered.

At a substitution of 10 mass% cement by greywake a increased strength was determined with increased thermal treatment of greywacke powder (Figure 12). At 950 °C, the strength of the starting cement is exceeded. At higher additive amounts, the influence of the increasing treatment temperature is less pronounced. Even with 40 % cement substitution with the greywacke powder – measured against the value calculated for an inert additive – good strengths were still obtained. From the results of the X-Ray analysis, it is derived that the amorphous content increases considerably as a result of the tempering.

6 Conclusions

Demands for material and resource efficiency have not only gained relevance, but now form a part of corporate strategy. That is where the idea of utilizing filler material produced during the extraction and production of high-grade aggregates comes in. Objectives of a research project sponsored by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy and supported by the industry were therefore relevant conclusions on the suitability of these rock powders as “supplementary cementitious materials”. The tests were conducted on a total of seven powders that originate from four basic and two acid rocks as well as the sedimentary rock greywacke. With regard to their chemical and mineralogical composition as well as their particle size distribution, precise analysis was necessary to obtain an overview and draw conclusions for more detailed studies. For selected samples, after strength tests on hardened cement paste prisms, tests on standard mortar prisms were performed. The following conclusions can be derived:

From the chemical composition of the powders, evaluated based on the three-phase system CaO – Al2O3+Fe2O3 – SiO2, it can be concluded that only the rhyolites and the greywacke have a composition typical of pozzolans. The diabases and the basalt are slightly to considerably outside the region of reactive additives. The basalt has an X-ray amorphous content of 40 mass%.

From the measurements on reactivity with the Chapelle test and the strength tests on hardened cement paste prisms, it follows that the diabase powders show no reaction potential and at best make a very small contribution to strength development. Although as a result of thermal treatment the content of the clay minerals in the diabases decreased and amorphous phases were formed, no activation could be achieved.

According to the Chapelle test, the basalt powder exhibited limited reaction potential, which could be related to the content of amorphous phases – 40 mass%. The measured strengths corroborate this conclusion.

In the case of rhyolite powder, with additional grinding, an increase in strength can be achieved. With a cement substitution of 10 mass%, the strength of the starting cement is slightly exceeded.

In the case of the greywacke powder, tempering results in reaction potential with an effect on strength. With the temperature treatment, X-ray amorphous phases are formed, which could be the cause for the contribution to strength development. A clear conclusion regarding the required treatment temperature is still required.

To explore the conclusions derived in greater depth, further tests on the powders with identifiable reaction potential are necessary. As influencing parameters, the granulometry and the level of the temperature treatment should be varied. It is also necessary to examine whether with a high cooling rate, the amorphous content can be increased and the reactivity improved.

//www.iab-weimar.de" target="_blank" >www.iab-weimar.de:www.iab-weimar.de

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.