Formation of hydrate spheres in ternary binder systems

This study examines the hydration kinetics of hydrate-sphere formation. This is a form of heterogeneous setting and can frequently be observed in ternary binder mixtures high in Portland cement and containing calcium aluminate cement and CaSO4, which are retarded by means of tartaric acid. In many cases, the phenomenon of hydrate-sphere formation is the result of aging of the dry mix – quick-setting ternary binder mixtures, in particular, are severely prone to pre-hydration once the package has been opened. Formation of hydrate spheres can be eliminated only to a limited extent via minor...

This study examines the hydration kinetics of hydrate-sphere formation. This is a form of heterogeneous setting and can frequently be observed in ternary binder mixtures high in Portland cement and containing calcium aluminate cement and CaSO4, which are retarded by means of tartaric acid. In many cases, the phenomenon of hydrate-sphere formation is the result of aging of the dry mix – quick-setting ternary binder mixtures, in particular, are severely prone to pre-hydration once the package has been opened. Formation of hydrate spheres can be eliminated only to a limited extent via minor adjustments of the formulation, with the result, ultimately, that the formulator is in many cases obliged to reevaluate the entire mineral binder system, including the retarder-accelerator system.

1 Introduction

The term “hydrate-sphere formation” designates detrimental heterogeneous setting of mixed-binder based mortars [1]. Hydration centers are formed, and grow into spheres in the centimeter size range (Fig. 1a). The viscous (unset) matrix sets hours later, or dries out. In thin-layer applications, such as self-leveling flooring compounds, for example, this phenomenon results in the generation of concentric mottling patterns in a cracked and soft matrix, which softens again immediately when wetted.

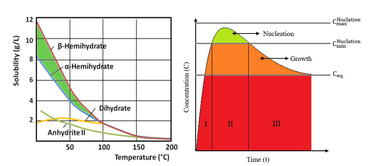

The phenomenon of the formation of hydrate spheres is encountered particularly frequently in conjunction with the aging of ternary dry mixes high in Portland cement content and containing calcium aluminate cement and calcium sulfates retarded by means of tartaric acid. Initial reaction-kinetic investigations of such binder mixture systems give rise to the theory that aging of the dry mix reduces the solubility of Ca ions during mixing with water, as a result of which a surplus of tartaric acid causes temporary inhibition of the hydraulic system [2].

There is, however, still room for speculation as to why the greatly retarded start of setting should take the form of heterogeneous generation of spheres around a few hydration centers.

In this study, we examine further calorimetric and X-ray diffractometric investigations of two formulations (Table 1). This kinetic data is discussed, together with microscopy-based findings (both light and scanning-electron microscopy [SEM], including element distributions), with the aim of achieving improved understanding of the heterogeneous formation of hydrate spheres.

The motivation to confront this topic originates, on the one hand, from the desire to describe the processes occurring during hydration, using scientific methods, and to develop corresponding models. In addition, an increase in damage associated with the heterogeneous formation of hydrate spheres in conjunction with quick-setting dry mortars is also observable in practical application.

2 Experimental results

Investigations up to now [1–2] have been performed on a model formulation of a pure binder mixture listed as “TMB” (Ternary Mixed Binder) in Table 1. In addition to the three binders, this formulation also contains tartaric acid and calcium hydroxide as the standard setting retarder and strength accelerator. These five components constitute the simplest formulation with which formation of hydrate spheres can be reproduced. Formation of hydrate spheres occurs to an even more pronounced extent if this dry mix is artificially “aged” (open storage, i. e., exposure, at a relative air humidity of 50 % and a temperature of 23 °C). The aged dry mix, reduced to five components, has a relatively high mixing water demand of up to 75 %. This, however, is unimportant, since this model formulation is not intended for optimization of fresh mortar properties.

In addition, the same tests were also performed on a real self-leveling compound (shown as “SLC” in Table 1), which was applied, in a manner closely approximating to everyday practice, in a thin layer of approx. 4 mm in depth. This is the same formulation as is designated “PC-dominated SLC” in Kighelman et al. [3]. Aging of this dry mix resulted in a special form of sphere-like bodies (Fig. 1b), which permit special insight into the mechanisms of this heterogeneous hydration. The special feature is the fact that the shell around the white core is not closed; it consists, instead, of an accumulation of irregularly shaped high-Al bodies (referred to below as “clots”), which are scattered in the adjacent matrix. This is obviously a specimen in which formation of hydrate spheres was just starting, but in which the matrix still set sufficiently early to ensure that, apart from mottling, no damage occurred as a consequence of greatly retarded setting. Particularly remarkable is the elevated level of porosity in the white core of these hydrate spheres (blue impregnation resin in Fig. 1c). Both formulations have similar relative binder ratios and both also contain calcium hydroxide and tartaric acid.

The calorimetric and X-ray diffraction methods used for this study are described in detail in [2]. Prior to the tests, the two mixes – TMB and SLC – were put into a Petri dish of 1 cm in height and then exposed for periods of three, seven and twenty-eight days at 23 °C and 50 % relative air humidity.

The heat-flow curve of the non-exposed TMB is shown together with the heat-flow curves after three, seven and

28 days of open exposure in Figure 2. Hydration starts in all cases immediately after mixing, with an energetic initial reaction, which has subsided after 0.4 h. This initial reaction is attributable to readily soluble phases of the clinker and the calcium hydroxide. This is followed by a retardation of hydration, thanks to the effects of the tartaric acid, and/or to a prolongation of the dormant period, with extremely low heat flow.

The precise time of maximum heat flow tmax is around 1.5 h in the case of the fresh, non-exposed TMB, whereas the mix that has been aged for three days reaches its maximum heat flow only after tmax = 2.5 h, and that aged for seven days after

tmax = 4.9 h. A broad second heat-flow maximum of 2.4 to

2.5 mW/g is apparent after 15, 19 and 24 h in all three measurements. The sample aged for 28 days exhibited no heat flow within 48 h from the conclusion of the initial reaction.

The phase developments of the fresh TMB and the TMB exposed for three days are shown in level plot diagrams in

Figure 3 (°2Theta CuK across hydration time). To permit direct comparison, the heat-flow curve is, in addition, also plotted along the time axis.

It is interesting that no primary calcium hydroxide (component of the dry mix; see Table 1) whatsoever is to be found at the beginning of hydration in the fresh sample (Fig. 3a). This obviously dissolves completely upon mixing with water and contributes to the highly exothermic initial reaction. Only after around 6 h does the formation of secondary calcium hydroxide (portlandite) start (reflexion at 34 °2Theta). The heat-flow maximum at 1.5 h coincides with the complete dissolution of the calcium sulfate hemihydrate (HH). The increase in the ettringite reflexion at 9.1 °2Theta starts after only 1 h. The calcium aluminate also required for ettringite formation is obviously supplied by initial dissolution of CA and C3A. Gypsum is temporarily generated after 4 h, but disappears again completely by 21 h, to be replaced by a less easily detectable AFm formation at 9.25 °2Theta, which is observable after 7.4 h. A clear decrease in alite can be detected after 14 h. In the case of hydration of the ternary mix exposed for three days (Fig. 3b), it is observable, generally, that all reactions are greatly retarded compared to the fresh ternary mix (Fig. 3a). Complete dissolution of the calcium sulfate hemihydrate (HH) is apparent only after 4 h, and an increase in the ettringite reflexion at 9.1 °2Theta starts after 3 h. Temporary gypsum formation occurs again – delayed by 2 h, however - and the formation of secondary portlandite only at around 23 h, for which reason this phase is not indicated in Figure 3b.

The heat-flow curves of a self-leveling compound (SLC), in one case fresh and in one case aged for 28 days, are compared in Figure 4. Open exposure of the dry mix for a period of four weeks for its part causes retardation of the first reaction maximum from 1.8 h to 3.9 h. The precise time of a second broad heat-flow maximum, which is observable for the freshly homogenized mix at 7.1 h, is detected, after 28 days of exposure of this dry mix, only after 13.5 h from mixing of the paste.

The initial reaction is, in the case of the aged compound, significantly stronger than in the test performed on the fresh dry mix.

The in-situ phase development in the first 24 h of hydration indicates that the second prolonged maximum of heat flow can be correlated to ettringite formation (Fig. 5). The dissolution of calcium sulfate hemihydrate (HH) is also retarded on the basis of direct comparison, from 8 h in the case of the fresh dry mix, to 15 h for the mix aged for 28 days. The immediate formation in the aged sample of secondary gypsum, which dissolves again completely at 18 h, is also conspicuous. Due to the limestone powder and quartz-sand contents in the formulation (SLC), it is not possible to state any information on the hydration of CA and C3A. Nor is any significant decrease in alite contents apparent in the first 24 h of hydration. Exposure of the SLC mix is in any case less greatly characterized by a retardation than the ternary mixture (TMB) with no additives other than tartaric acid (see Table 1).

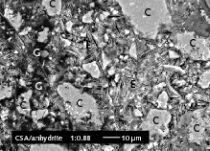

The SEM images and element mappings for Al, Ca and S are shown for the TMB sample (left-hand column: a, c, e, g) and the SLC sample (right-hand column: b, d, f, h) in Figure 6. The samples are the same as those shown in Figure 1. Figure 6a is a detail from Figure 1a.

The procedure for sample preparation was as follows: the formation of concentrically zoned hydrate spheres on the beaker walls and on the underside, towards the plastic foil, is observable when the dry mixes are mixed in beakers with water and set there, or when the mixed paste is spread on plastic foils. The centers of the hydrate spheres obviously form on or adhere to the interfaces (beaker walls, plastic foil) and the thus restricted growth results in the formation of a hemisphere with a central cross-section at the beaker wall or the plastic foil. These central cross-sections through hydrate spheres frequently appear when the sample is demolded or the plastic foil is peeled off. In our case, these surfaces were sufficiently smooth to permit their examination under the scanning electron microscope after carbon coating but without further polishing.

In the case of TMB (Fig. 6a, c, g, e) it should be noted that the distribution of the potassium follows the pattern of Al and S, whereas Si and Fe are distributed in a manner similar to Ca.

The same applies to the SLC sample (Fig. 6b, d, f, h), with

the exception of the fact that sulfur (Fig. 6h) exhibits its own rhythmic zoning pattern.

Sample TMB (left-hand column in Fig. 6) exhibits two shells (S1 and S2) around a white core (C). The outer shell (S2) manifests the same element contents as the core (C), whereas the chemical composition of the inner shell (S1) corresponds more to that of the matrix material (M). The observation that the spheres are initially small and then become increasingly larger [1] permits the deduction that these bodies grow from the inside outwards. The first shell grows once the white cores have formed. Growth of this initial shell then stops, and a second, outer shell with a composition similar to that of the white core is generated. The composition of the solution has obviously modified to such an extent that it now behaves again as it did at the start of sphere formation. Composition then changes for a second time, however, and the matrix, which has an elemental composition similar to the inner shell, sets.

We have here an example which indicates that the cyclically alternating formation of two differing element distributions in shells may be associated with fluctuations in pore-solution composition.

The element distributions in the second sample (SLC, right-hand columns in Fig. 6) in some cases exhibit other patterns. Here, too, sphere growth starts with the formation of highly porous white cores (Fig. 1c). The high-Al clots then obviously form. These are darker, i. e., less dense, on the backscattered electron image (Fig. 6b). The substance involved here is probably Al-hydroxide gel, since all other elements measured are greatly depleted in these zones. These clots are embedded in a matrix which exhibits an extremely interesting distribution pattern for sulfur. Rhythmic, non-regular but concentrically arranged accumulations occur (Fig. 6h). These rhythmic accumulations disclose continuing fluctuations in the precipitation of sulfur, which can be located, as shown in the X-ray diffraction studies (Fig. 5), in the ettringite phase.

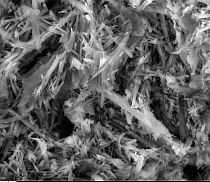

The fact that this system is still capable of generating ettringite as the main hydrate phase is indicative that the ettringite-based binder system as such is still functioning. The X-ray diffraction investigations (Fig. 3), on the other hand, show that not only ettringite, but also the monosulfate phase, is formed in the TMB sample. These are clear indications that the mixed-binder (TMB) is no longer functioning as a pure ettringite system.

3 Discussion of results

The calcium hydroxide in the TMB dry mix appears to play a key role in the formation of hydrate spheres. It seems, after mixing with water, to dissolve immediately, with the result that it cannot be measured by means of in-situ X-ray diffraction analysis, despite the fact that, at 2.2 wt. %, the proportion in the dry mix is relatively high, and should, at this level, actually be detectable by the X-ray diffraction method. This rapid dissolution may make a definitive contribution to the pronounced exothermic nature of the initial reaction (Fig. 2). Thermo-analytical investigations have shown that the calcium hydroxide is continuously consumed as aging of the TMB dry mix progresses, with the result that it is less available upon mixing with water in greatly aged samples [4]. It is probably converted to hydrates and carbonates, which are only poorly soluble.

In the aged TMB sample (Fig. 3b), the intensity of the X-ray reflexions during the dormant period (between around

20 min. and 1 h 20 min.) appears to fluctuate. This could be an effect resulting from the high water/solid ratio of 0.75 (bleeding of the sample), or elevated formation of gel in the system. The latter could provide an interesting clue to the formation of sphere centers – a gel-like consistency is apparent when attempts are made to fish these around 1 mm large sphere centers out of the liquid mass. The spheres start to solidify only as they increase in size. An early gel formation in the system would be in accordance with increased porosity, which is to be observed in the cores of the hydrate spheres (Fig. 1c). The detection of Ca enrichment in the cores of the spheres in combination with a depletion of Al and S is of special interest. This indicates that Ca is provided by the hydrating system whereas the aluminate and CaSO4-phases are less readily dissolved at that time. An

X-ray diffraction diagram of a TMB sample aged for 28 days (Fig. 7) shows total inhibition of the system for 48 h. None of the primary phases (calcium sulfate hemihydrate and clinker phases) exhibit any decrease, and appear not to dissolve further at all. Instead, a greatly elevated background becomes apparent in the 2Theta range between 25 and 30 ° during

the first 24 h and could indicate an amorphous fraction (e. g. a water-rich Ca-tartrate gel) in the system, capable of fixing a large amount of free water and coating the potentially reactive phases [5].

The in-situ X-ray diffraction analyses indicate that the SLC sample continues to behave as an ettringite-based binder system even after aging. Aging of the TMB sample, on the other hand, causes a modification in the formation of hydrate phases with monosulfate, which is generated in addition to ettringite.

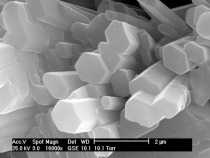

The formation of monophases can be confirmed by means of scanning-electron microscope analyses [1]. Predominantly hexagonal platelets with the crystal morphology typical of monosulfate were ascertained, in addition to the typical ettringite needles.

An early stage of the damage history seems to become clearly apparent in the aged SLC sample. Secondary gypsum starts to form even immediately after mixing (Fig. 5b). This indicates that insufficient calcium aluminate phases are able to dissolve, and that ettringite formation is thus inhibited. A temporary deposit of CaSO4, in the form of dihydrate, is generated instead. Ettringite formation gains in pace only during the exothermic period at 3.9 h (Fig. 5b), and ensures solidification as a result of H2O incorporation in the 8 to 17 h period. Applied as a thin layer, such a greatly retarded hydration would long have been preceded by drying, and the flooring compound would be able to achieve only inadequate strength. Such a dried out layer of mortar would simply soften again if wetted with water. The aged SLC sample could in this case already cause damage.

Pre-hydration had extremely differing effects in the two dry mix compositions used in our investigation. Despite an identical period of exposure, the more complex (due to additive and other admixtures) SLC binder was less severely retarded than the TMB sample.

4 Model of formation of hydrate spheres

Aging of the dry mix may possibly cause consumption of the primary calcium hydroxide and result in premature reaction of the clinker phases, due to carbonation and hydration reactions. High-reactivity clinker phases (free lime, alkali sulfates and very reactive calcium aluminate phases) are, in particular, especially susceptible to pre-hydration. This greatly reduces the rates of dissolution of all the elements involved (Ca, Al, S).

The tartaric acid used as a retarder continues to dissolve at the same rate, irrespective of the aging of the dry mix, and is thus present in a disproportionately high amount in the pore-water

solution. Less rapid reduction of tartaric acid concentration, which could be degraded with Ca ions, results in retardation of hydration as a whole [6]. If this state continues for too long (as a consequence of severe aging, resulting in the formation of relatively thick impermeable hydroxo-hydrate layers around the particles of cement), the tartaric acid can no longer be consumed at all and the system is now inhibited not temporarily, but permanently.

These new investigations indicate that the hydrate sphere phenomenon could be related to pronounced generation of Ca-tartrate gel. This, on the one hand, causes a very large amount of free water to be unavailable to the hydration reactions and, on the other hand, a drastic reduction of diffusion rates throughout the system.

Not yet explained is the observation that small gel-like accumulations start to form in the temporarily inhibited system after a time which is dependent on aging of the dry mix, and that the following formation of hydrates is located to these primary accumulations, which then grow to centimeter sized spheres (heterogeneous hydration).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Markus Bernhardt and Tobias Danner, who were involved with the experimental work at the Mineralogical Institute, GeoZentrum Nordbayern (University of Erlangen), and Marco Herwegh for the element mappings performed at the Institute for Geological Sciences (University of Bern). Special thanks go to Jürgen Neubauer (University of Erlangen) for the very helpful and unflagging discussions on the formation of hydrate spheres.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.