Comprehending the lime production process

Lime production is a complex process that calls for an increasingly deep level of process comprehension. The fact that legislators keep stipulating ever lower emission levels, coupled with ever increasing energy and maintenance costs in connection with the production process, makes such comprehension more necessary than ever. Since any change of generations tends to involve the loss of much experience, this article is dedicated to passing on a plethora of long-standing, fundamental, practical experience as a collection of information leading to improved process comprehension, particularly for young technical and managerial personnel.

1 Introduction

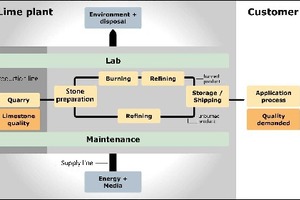

As shown in Figure 1, the overall lime production process basically consists of two lines, the first of which, the production line, essentially comprises the following operations: quarrying, the actual industrial process (incl. the individual sub-processes: stone preparation, calcining, refining and storage/dispatch) and the application processes. The other, the supply line, begins with inputs of energy and additional media (fuel, water, air, etc.) and ends with environmentally relevant emissions and the disposal of media. In principle, the individual stages of the overall...

1 Introduction

As shown in Figure 1, the overall lime production process basically consists of two lines, the first of which, the production line, essentially comprises the following operations: quarrying, the actual industrial process (incl. the individual sub-processes: stone preparation, calcining, refining and storage/dispatch) and the application processes. The other, the supply line, begins with inputs of energy and additional media (fuel, water, air, etc.) and ends with environmentally relevant emissions and the disposal of media. In principle, the individual stages of the overall industrial process can be depicted according to the configuration of the overall process. The two lines are closely linked, so any change taking place in one line also impacts the other.

The starting point of contemplation with regard to the production line is where the customer specifies what they want to see fulfilled by the lime product. The next step is where the initial qualities of the quarried limestone are injected into the calculation. Then, the applied technology, up to and including the supply line, must be adapted to ensure that the produced lime is of uniform quality. In most cases, the quality of the lime at that point (high or low) is still irrelevant. What counts is that the quality remains constant, thus enabling the customer’s (application) process to be adjusted to the quality of the delivered lime. Any fluctuation in the quality of that lime would cause problems for the customer’s process.

The central process of lime production is the calcination, or burning, of the limestone in a lime kiln, in the course of which the limestone converts to lime. It is a frequently overlooked fact that any attempt to optimize the operations of production must start with the calcining process. This process must be coordinated in such a way that the customer’s lime-product specifications are fulfilled and that the environmental specifications for approval (emissions, etc.) are satisfied. If any problems are encountered with regard to the quality of the lime or the achieved emission levels, the engineering of the lime production process has to be revised accordingly.

Comprehension of the complex lime production process is dealt with via the following observations. It is shown that it takes a structured procedure and the help of certain tools to establish the causes of and solutions to any such problems. From a managerial point of view, in order to ensure long-term success, all employees directly involved in the process should also be involved in finding the solution.

2 Structured approach to investigating

the lime production process

The quality of lime produced by calcination basically depends on the type of kiln employed, its operating mode, the quality and condition of the limestone, and the type of fuel used for firing the kiln.

The following reflections can neither delve too deeply nor offer any all-in solutions, as that would exceed the scope of this article. On the one hand, the preferred procedure will always depend on the actual nature of the problem, and on the other hand, on the circumstances prevailing at the lime works. Discussions pertaining to potential causes and solutions should always take place on the same premises. In that connection, some steps of work described as being necessary for a structured procedure are, in reality, usually not taken in consideration.

The first step toward establishing the cause of a problem is to be familiar with the given situation at the lime works. This includes knowing the properties of all material passing into and out of the kiln, along with the respective paths of infeed and discharge and their effective data. It is essential that those data be monitored over a prolonged period of time in order to identify and document production fluctuations and to evaluate their impact on lime quality.

3 Required data

The following data are required for a detailed evaluation:

3.1 Input material

a) Limestone: So-called lime-kiln stones progressing between extraction from the quarry, subsequent preparation, and transfer to the kiln:

geometric data: particle size, incl. oversize and undersize, particle size distribution, particle shape (cubic, flaky)

chemical data: composition (CaCO3, MgCO3, SiO2, inert components, …), other impurities, presence/absence of adhesions (clay/loam, sand, ….), general cleanliness, water content

thermal data: heat conduction through the lime layer of the limestone/lime particles, reaction coefficient of calcination within the calcination front

physical data: strength, porosity

limestone burnibility data: (i.e., achievable lime quality in terms of reactivity, rate of conversion, max. calcining temperature, sticking/caking tendency)

operating data (input quantity [kg/h]; temperature [°C])

b) Fuel: Distinctions must be drawn between the various types of fuel that are used for burning lime. Only standard-type fuels are dealt with here:

gaseous fuel: natural gas, coke-oven gas, etc.

chemical composition, density

operating data: input quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C] and pressure [bar]

coarse or powdered fuel: coke, anthracite, pulverized lignite or anthracite

chemical data: elemental analysis (C, H, N, O, S), volatile constituents fraction, proximate analysis (water and ash contents), water content on analysis, fuel value (differentiated according to fuel: raw, free of water and ash), components of ash composition, as applicable):

geometric data: particle size, incl. oversize and undersize

physical data: strength of lumpy material

operating data: quantity [kg/h], lumpy material: water content on loading, temperature [°C]

liquid fuel: heavy or light oil

chemical data: elemental analysis [C, H, N, O, S], proximate analysis (water and ash content), fuel value (differentiated according to type of fuel: raw, free of water and ash)

operating data: quantity [l/h], water content on loading, temperature [°C]

c) Air:

combustion air: operating data (quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar])

lime cooling air: operating data (quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar])

conveying air for pulverized fuels: operating data (quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar])

supplementary cooling air (for cooling refractory walls, fuel lances, etc.): operating data (quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar])

d) Other media: e.g., water or oil used for cooling furnace internals or burner lances: operating data (quantity [l/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar])

3.2 Output material

a) Lime: so-called run-of-kiln lime:

geometric data: particle size, incl. oversize and undersize, particle size distribution

chemical data: composition (CaO, CaCO3, MgO, inert components, residual CO2 content, water content)

quality data: reactivity (t60-value [min.]), residual CO2 content, whiteness

dust discharge volume: composition (CaO, CaCO3, MgCO3, MgO, inert fractions, deriving to limestone/lime), discharged quantity [kg/h], temperature [°C])

operating data: discharged quantity [kg/h]; temperature [°C]

b) Exhaust: exhaust gas analysis: CO2, CO, O2

operating data: temperature [°C] and pressure [bar]

c) Air: unused lime process cooling air:

operating data: quantity [Nm³/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar]

d) Other media:

e.g., water or oil serving to cool the kiln internals or burner lances: operating data: quantity [l/h], temperature [°C], pressure [mbar]

Special reference is made to the fact that the gas volume flows are stated in Nm³/h. Often, during actual operation, no differentiation is made between standard and actual cubic meters. The standard state is defined as being at a temperature of TN= 273.15 K (corresponding to 0° C) and a pressure of pN = 1.01325 bar (corresponding to 760 torr). Actual volume flows can be converted into standard volume flows on the basis of known temperatures and pressures.

It is advisable to question all data, especially data provided by suppliers, because they serve as the basis of all further calculations within the measured-value capture and evaluation system. For example, the heat content of solid fuel can vary over time, and all inquiries should include mention of the reference value.

With regard to both incoming and outgoing material, the extent to which the flow of material is exposed to seasonal climatic conditions must be taken into account. Freezing temperatures and precipitation can have considerable impact on the properties of mass-flow material. The number of transfer points and the discharge height of solid material (limestone, lime, solid fuels, …) have impacts on both dust formation and the particle-size distribution. That, however, is undesirable. In most cases, such conditions tend to set in when the quarry is being readied for a weekend or public holiday, so the material can be exposed to unfavorable weather conditions, possibly over an extended period, if it is not properly protected for the interim. The fill level of material stored in a silo subsides over weekends and holidays, hence increasing the in-silo discharge height, thereby causing more dust to form and diminishing the particle size. This problem persists until the silo is refilled on the first working day to follow.

One frequently made mistake is to choose too small a mesh size for screening the lime before it enters the kiln. This increases not only the quantity of limestone entering the kiln, but also the amount of undersized particles. From a process engineering point of view, this means that the void fractions of the lime column in the shaft kiln decrease together with the gas permeability level. It is frequently observed that fine material accumulates at the center of the kiln axis, resulting in an uneven cross-sectional flow of gas through the kiln. This, in turn, alters the kiln’s cross-sectional firing conditions, as subsequently observed in terms of lower lime quality and higher pollutant emissions. The employed blasting technique can also influence the particle-size distribution of the quarried material. In that connection, it is advisable to consult an expert blaster for advice on how to appropriately modify the blasting process.

3.3 Knowledge of existing resources

The quality of reserve resources at the quarry is not always known to the operators of lime works. However, it must be ensured that the quality of the product received by the customer remains homogeneous. Consequently, the deposit in question has to be well explored in order to secure a good working knowledge of its long-term quality. The findings gained from exploration may also have ramifications for the mining operations plan and/or for the longevity of the deposit itself. At many plants, the latter receives only half-hearted attention or remains underestimated. In the course of his own professional practice, this author has learned that, as a rule, it only makes sense to invest in plants with a projected service life of more than 40 years. Otherwise, the plant in question should only be maintained to such an extent, that the requisite expenditures ensure its continuing functionality. In other words, the plant should be gradually phased out. This rule also reflects the fact that most such property is acquired over generations, i.e., thus covering substantial spans of time. The time factor also derives from the fact that as-yet unpurchased property may first require examination not only in terms of quality, but also in order to establish whether any other interests, perhaps of a public nature, still exist.

On the basis of the above considerations, it is a good idea to perform a general, structured investigation of lime production from time to time in order to keep tabs on the plant’s current status. This includes consideration of which products are to be manufactured in the future. In general, it takes a year or so to correspondingly adapt and adjust a plant’s production-process technology, since official approvals usually have to be obtained.

4 Measured-data acquisition

The second step in analyzing the lime production process is to check which measured data are being recorded by the operational measuring system.

Frequently, it turns out that lots of data are being recorded, but no one is paying any attention. Often enough, no one knows how the data are being generated or for which kind of process interpretation they may be required. Conversely, some data that are essential for evaluating the process may not be being recorded. If that is the case, the company cannot gain a proper overview of the individual processes, particularly with regard to the kiln and all its various interdependences. If so, expert advice in the form of a structured investigation of the plant’s status quo is called for.

A good heat- and material-flow analysis counts among the essential tools for shaking down the lime production process. The results illuminate lots of information, provide answers to questions concerning the current operating status, and allow a check of the measured values’ representativeness.

Initially, the material flow analysis need only extend up to the lime kiln. This suffices to show which quantities of burnt and unburnt product are being produced. The aim here is to optimize the proportion of burnt product, because it yields the higher margins, thereby helping to increase the plant’s profitability. Pertinent micro-economic considerations help find and set targets, the realization of which, however, always requires technical monitoring. The sales department must ensure that there is sufficient market demand for appropriately conditioned unburnt products. It is important to understand that uncalcined products are to be regarded as co-products of the calcined array.

4.1 Heat- and material-flow balance

A heat- and material-flow balance needs to be drawn up for the lime kiln to achieve optimized use of materials and heat. The author relies in principle on two types of heat-and-material balances: one static and the other dynamic.

4.1.1 Static balance

The static balance is basically the result of calculating the output (discharged) flows of material at their given temperatures at the balance boundaries, i.e., at the kiln inlet (exhaust gas) and kiln outlet (lime).

By comparing the calculated values with the actual values, this balance can be used to relatively quickly check if the balance is closed, i.e., if the data derived at the measuring points (e.g., for pressure, temperature, flue gas analysis and quantity) actually are representative. This form of closed balance offers the advantage that the in-kiln conditions can be documented in a single diagram.

Comparing the measured values with the theoretical values is particularly helpful in the case of standard, mix-fired shaft kilns operating on coke or anthracite. After any re-adjustment of parameters, such kilns need two or three days’ time to reach a quasi-steady thermal state.

4.1.2 Dynamic balance

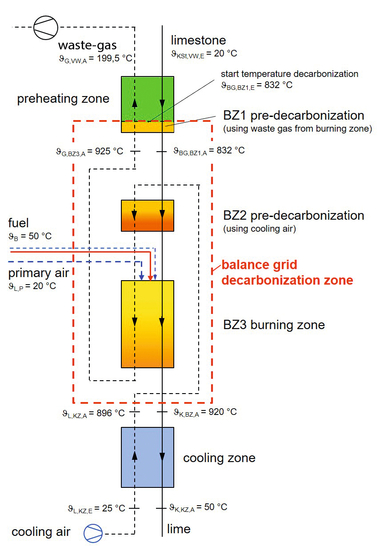

A more complex approach, the dynamic balance, is based on a mathematical model developed in cooperation with the University of Magdeburg.

It can be applied to PFR-type and standard shaft kilns in which the fuel is fed to the burners at one or two kiln heights in the lower half of the kiln, with distribution taking place via the kiln shell. RCE and HPS kilns built by Maerz belong to this category. A standard-type shaft kiln with mixed solid-fuel firing is presently under development.

In contrast to a static balance, this model can be used for calculating in-kiln temperature profiles for limestone/lime and gas (air and combustion gases). This way, the kiln’s length and the length of the individual process zones (preheating, firing and cooling zones), i.e., the kinetics of heat transfer and lime burning throughout the kiln, are all taken into account. A limestone fraction with influence on the kiln’s pressure differential and on the degree of conversion of the individual fractions can be specified for the calculation.

The results of such calculations (gas and solid temperature profiles) have been compared with data taken from thermocouples passing through a real kiln, corresponding to the progress of the limestone/lime column and showing concordant results. These calculations also make use of the aforementioned thermal limestone data.

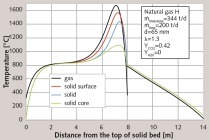

The thermal data are explained in Figure 2 in order to illustrate their importance.

Figure 2 represents a section of a limestone particle, whereas the full particle is assumed to be spherical in shape. While this assumption never actually holds true in practice, it does facilitate the interpretation. The lower part of the illustration shows that the particle has a limestone core (CaCO3) and a lime (CaO) shell. Calcination of the limestone/lime particle is a topochemical process that progresses from the lime shell to the core of the particle. The process of deacidifying the particle can be visualized as a series of interconnected resistors.

The process gas, with the temperature Tg and pressure pg, is located outside of the particle. At first, heat from the process gas is transferred to the surface of the particle by radiation and convection. This is represented by the resistor Rα.

Then, the heat is applied by thermal conduction to the calcination front, where the endothermic calcination process (via heat input) takes place, as represented by resistor Rλ. In actual practice, the quantifiable level of thermal conductivity within the lime shell may differ from theory. If it is lower, it will take a larger difference in temperature between the surface and the calcination front to provide sufficient energy for the endothermic process. However, this also means that the surface temperature will be higher. If less heat is transferred to the limestone/lime particle, the temperature of the process gas and of the particle surface will rise. This increases the risk of formation of agglomeration/sticking of particles, if the temperature exceeds that of the particle surface. Variations in thermal conductivity clearly show differences in the results obtained for the theoretical quality of the lime product, e.g., the residual amount of CO2 in the lime particle increases.

The reaction coefficient of calcination can take on different values, too. Investigations have shown that enormous differences can occur among limestone particles, even in particles stemming from the same deposit (represented here by the resistor Rk).

The resistors RD and Rβ stand for the diffusion of CO2 gas to the particle surface and for the mass transport to the process gas. It has been shown in practice that those two resistors play a subordinate role in the calcination process, as long as the particle surface does not become gas-tight due to overheating or melting.

The upper part of the illustration shows the pressure and temperature curves.

Ultimately, this illustration shows how important it is for the heat source (fuel combustion) in the lime kiln to locally match the heat sink (heat absorption by the limestone/lime particle) in order for optimal process conditions to prevail.

Both balances, static and dynamic, serve excellently as tools for increasing process comprehension and evaluating the lime production process. However, any actual investigation of the causes and the finding of solutions to furnace problems will necessitate the consideration and evaluation of additional kiln data. That, in turn, calls for appropriate, pertinent experience and process-engineering knowledge of the complex lime production process. It should be kept in mind that refractory technology also exerts a major influence on kiln operation.

4.2 Responsibilities and controlling

As the author’s experience shows, it is advisable for each plant to have at its disposal relevant competence for quick intervention in the event of a malfunction. The reaction time following a kiln malfunction is a decisive factor for limiting the extent of damage. Consequently, a responsibility matrix specifying just who is supposed to adjust what, when and how with regard to the kiln should be readily available. This prevents kiln operators from individually changing the kiln’s mode of operation from one shift to the next. Training courses geared to extending the depth of comprehension are also recommended. Employees should be made sensitive to the need for keeping an eye on such inputs as fuel and limestone as part of their routine inspection tours.

Occasional manual sampling of lime from the individual kiln outputs is also necessary. The analysis of such samples ultimately provides information regarding the status of the kiln. It should be noted in this connection, that, while the results of manual sampling may be regarded as merely representative due to inaccurate data, they do call attention to trends. The evaluation of automatically drawn and prepared samples (stemming as a rule from an 8-hour shift) always yield reproducible values.

5 Summary

The production of lime is a complex process that requires ever-increasing process comprehension.

The customer’s own lime specifications and the quality of the quarried material mark the starting points for all relevant investigations. Ultimately, it takes an appropriately equipped production line to guarantee targeted lime qualities.

The core component of any lime plant is its kiln, in which limestone is converted into lime. All operational investigations begin with a lime kiln assessment. The given qualities of the reserve resources are then considered to answer the question of how well the customer’s existing technology can satisfy the specifications and, if so, at which cost. Any deviations found would signal a need for action to analyze the existing qualities of the reserves together with the lime production process.

In order to implement structured investigations of problems affecting the lime production process with the intention of establishing the cause and working out a solution, it is important to possess an insightful, in-depth comprehension of the process. An essential part of truly comprehending the lime production process is to understand the mechanisms of heat transfer in the calcining process. For the purposes of structured investigation, two tools are helpful: static and dynamic heat and mass balances. In order to meet customer specifications over the long term, it is important to be familiar with the qualities of the as-yet unmined reserves.

From time to time, it is advisable to draw up a status quo of the lime plant in order to delineate its service-life expectancy, the existing qualities, varieties and an operations plan.

//www.iwp-gmbh.de" target="_blank" >www.iwp-gmbh.de:www.iwp-gmbh.de

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![2 Limestone-particle calcining model [1]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/0/8/1/4/1/tok_517f61b5f914bd2e288ba0ae09d38162/w300_h200_x421_y297_Kehse_Kalkwerk_Bild_2_en__Kompatibilitaetsmodus_-692cad53da2766b5.jpeg)