Co-processing – resource preservation in a resource intensive industry

An increasing demand in emerging economies, combined with resource scarcity, pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, increasing consumption and subsequent waste generation, makes low grade resources and waste treatment in resource intensive industries (RII’s) an interesting opportunity. The overall objective of this paper is to present best practices that constitute a benchmark for cement plants co-processing alternative fuels and treating hazardous waste.

1 Introduction

The development of a proper waste management infrastructure is not only required to protect human health and the environment, but it is necessary to sustain further development of their economies (Council Directive, 2000; IPPC, 2007). Many countries do not have a proper waste management infrastructure in place (Karstensen, 1998 and 2001b).

Often, the industry and/or the public society have limited options available to treat their waste in a cost-effective and an environmentally sound manner. For example, liquid organic hazardous waste, including oily waste, are frequently used in...

1 Introduction

The development of a proper waste management infrastructure is not only required to protect human health and the environment, but it is necessary to sustain further development of their economies (Council Directive, 2000; IPPC, 2007). Many countries do not have a proper waste management infrastructure in place (Karstensen, 1998 and 2001b).

Often, the industry and/or the public society have limited options available to treat their waste in a cost-effective and an environmentally sound manner. For example, liquid organic hazardous waste, including oily waste, are frequently used in small furnaces and boilers without any control or traceability.

Human and industrial activity leads to increased levels of waste generation, long before proper treatment means are available. Sometimes, temporary solutions are implemented, such as on-site storage or temporary landfilling. Countries are, therefore, faced, not only with the management of current waste production, but also with the management of stockpiles of stored waste (Karstensen, 1998). On the other hand, concrete is a basic construction and development element requiring huge amounts of energy and mineral resources and more and more large cement plants have begun to spring up.

If professionally managed and controlled, the cement industry is able to support industry and the community with a complete service, which is a viable, economical, local, environmentally friendly sound option for treating many hazardous and non-hazardous industrial and municipal waste. As compared to other treatment processes, co-processing in cement kilns requires no major investments and creates no liquid or solid residues. They are already in place with proper infrastructure. Cement kiln co-processing can therefore be extremely attractive under proper guidance, regulation and control everywhere including in emerging economies. Co-processing practises need, however, to be anchored in a national policy.

The UN COP 10 just endorsed, in October 2011, a proposal for “Technical guidelines on the environmentally sound co‑processing of hazardous waste in cement kilns” (//www.basel.int" target="_blank" >www.basel.int:http://www.basel.int).

2 The cement industry

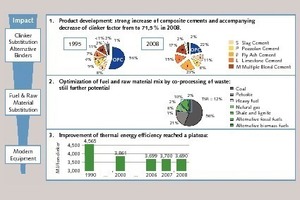

In 2010, the worldwide cement production was over 3 billion tonnes, including China, which is responsible for approximately 60 % of the world production capacity. Estimations put a world cement consumption at well over 3.5 to 4 billion tonnes by 2020 with a corresponding increase in energy, required raw materials and pollutant mass emissions. Consequently, the main ways (Fig. 1) to minimize the environmental and CO2 impacts of the cement sector are:

Maximize the efficiency of the manufacturing process and associated equipment to use fuels and materials as efficiently as possible – With the development of BAT technologies, the potential savings will remain marginal in future,

Reduce the amount of traditional natural resources and fossil fuel used in the process by increasing the use of low-grade resources and waste (Karstensen, 1994),

Increase the portfolio of cement by replacing raw material for clinkerization or clinker in cement with alternative minerals compounds having pozzolanic or hydraulics characteristics.

3 Guideline for co-processing

Enforcement for co-processing best practises are production, regions or country specific and local circumstances, such as regulation, raw material chemistry, availability of low-grade resources and waste, infrastructure and production process specificities, health, safety and environmental issues (GTZ-Holcim, 2006; WBCSD, 2006; Basel Convention, 2007 and 2011; Karstensen, 2009 a and b).

The detailed and final description of the pre-processing and co-processing best practises must be embedded in the local permit. This will ensure that complying cement plants will be feasible, qua-lified and will operate according to internationally recognised environmentally sound management principles (OECD, 2004; Federal Register, 1999 and 2005). The fundamental and overarching principle of the guidelines presented here is to prevent that inappropriate waste are used and/ or emissions will be influenced.

4 Policy elements

The authors recommend that a national policy on waste management is in place to ensure that the development, implementation of strategies, legislation, guidelines, plans, treatment options and other elements of waste management will be exercised in accordance with the following guiding principles (Karstensen, 2007 and 2008a):

A Cement kilns shall primarily be used for recovering energy and materials, i.e. for co-processing alternative fuels and raw materials, which can substitute parts of the fossil fuel and/or virgin raw materials;

B In the case of a lack of available treatment options and urgent needs, a suitable cement kiln can be used for treatment of organic hazardous constituents if this is done under strict control and government guidance. Such activities must have a special permit and must comply with specific guidelines (Karstensen, 2001a; Karstensen et al., 2006).

C The national policy should aim for sustainable resource and energy consumption and comply with relevant international conventions.

A legal framework must cover all aspects of co-processing of AFRs and treatment of hazardous waste in cement kilns by describing international recommendations and environmentally sound management principles (Karstensen, 2007 and 2008a). These principles must however, be adapted to applicable laws and regulations regarding waste types and characteristics, pre-processing facility, and the co-processing at the local cement plant (Karstensen, 2006b).

The final co-processing and treatment at the cement plant will be determined by the individual specification and chemistry, by the availability of feedstock waste material and AFR, by the infrastructure and the cement production process, by the availability of equipment for control and monitoring, handling and feeding the AFR, and finally by site specific health, safety and environmental issues.

5 Generic foundations and strategy

The operator of the cement kiln must put in place all business foundations and a clear business development vision and strategy. Due to past experiences, it is recommended that a project scheme be built in four steps as follows:

1. Project foundation (project board, project manager, human resources allocations, endorsement of generic co-processing statement and policy, acceptance of environmental rules, communication strategy etc.).

2. Project basis analysis:

Technical assessment, limits and opportunities.

Waste market overview, competitor analysis, etc.

Legal frame overview on federal, regional and local level.

3. Business planning and strategy

Defining the company business model, objectives and targets.

4. Project development

Permitting, quality control system, design of specific pre- and co-processing installations etc.

6 Co-processing business model

Experience proves that the following business model is the most relevant:

Each cement operator must create a services oriented co-processing business unit.

Objectives: interface between the waste market and the kiln operator for waste pre-processing and internal relation as there are identification, control, and delivery to the cement facility or marketing.

7 Waste acceptance and quality control systems

The aim of the initial acceptance procedures is to set the outer boundaries and limits for waste that can be accepted by the particular kiln, and the conditions and requirements for their preparation and delivery specification (Oss and Padovani, 2003; Neosys & Ecoscan, 2004). Any waste co-processed should follow specific criteria clearly defined between the waste pre-processing facility and the cement operator.

8 Assessment of possible impacts

When the cement plant operator and the pre-processing facility have received information about the waste, they must:

Assess the potential impact of transporting, unloading, storing, and using the material on the health and safety of employees, contractors, and the community. Ensure that equipment or management practices required to address these impacts are in place,

Assess what personal protective equipment will be required for employees to ensure a safe handling, particularly of hazardous waste on site;

Assess the compatibility of waste streams. It is mandatory that reactive and non-compatible waste must clearly be separated and not mixed;

Assess which effect the waste may have on the process operation. Chlorine, fluorine, sulphur, and alkali content in waste may build up rings and blockages in the kiln system, leading to accumulation, clogging, and unstable operation; excess of chlorine or alkali may produce cement kiln dust or bypass dust (and may require installation of a bypass) which must be removed, recycled or disposed of responsibly. The heat value is the key parameter for the energy provided to the process. Waste and insufficient pre-treated AFRs with high water content may reduce the productivity and efficiency of the kiln system and the ash content affects the chemical composition of the clinker and cement and may require an adjustment of the composition of the natural raw materials mix;

Assess the potential impact on process stability and quality of the final product;

Assess the effects waste may have on plant emissions;

Evaluation of new equipment or procedures are needed to ensure that there is no negative impact on the environment (Karstensen, 2008b; Karstensen et al., 2010);

Evaluation and cross check of material analysis data;

The waste supplier has to be committed to provide data with each delivery, and each load needs to be tested prior to discharge at the site.

9 Commonly restricted waste

The following is a list of residues and waste, which are not acceptable for pre- and co-processing activities:

Electronic waste and entire batteries due to the very high level of heavy metals,

Infectious and biological active medical waste (it is mandatory to handle those types of waste in “closed boxes” to avoid leakages and contact to operators when directly injected into the kiln),

Mineral acids and corrosives have no added-value for the clinker process,

Explosives,

Asbestos has to be destroyed in full melting processes (clinkerization is a partially melting process),

Radioactive waste,

Unsorted, untreated municipal waste before mandatory sorting (high content of water and other uncontrollable disturbances).

10 Waste pre- and co-processing

The use of waste must not detract from a calm and continuous cement kiln operation, product quality, or the site’s normal environmental performance; implying that waste used in cement kilns must be homogenous and have a stable chemical composition and heat content, and a pre-specified size distribution. Pre-processing waste as a feedstock with the objective of providing a more homogeneous feed and more stable combustion conditions may become necessary.

Techniques used for waste pre-processing and mixing are wide ranging, and may include:

1. Mixing and homogenising of liquid waste to meet input requirements, e.g. viscosity, composition and/or calorific value;

2. Shredding, crushing, and cutting of large bulky waste, e.g. tyres or biomass;

3. Mixing in a bunker using a grab crane or other machines (e.g. pumps for sewage sludge or pasty material);

4. Production of RDF for the calciner or SRF for main burner, usually produced from preselected industrial solid waste and/or other non-hazardous solid waste.

11 Fuel feeding points

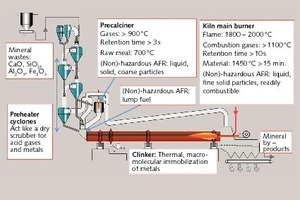

Feeding points to the pyroprocess system are (Fig. 2):

SRF and liquids to the main burner at the rotary kiln outlet end;

Feeding chute at the transition chamber at the rotary kiln inlet end (for lumpy size);

Fuel burners to the riser duct;

Pre-calciner burners to the pre-heater;

Optionally to a feeding chute or pre-combustion devices in the pre-heating process

Mid-kiln valve to long wet and dry kilns (for lump fuel).

12 Co-processing of hazardous waste

Hazardous waste has to be injected into the high-temperature combustion zone of the kiln system, i.e. the main burner, the pre-calciner burner, the secondary firing at the preheater, or the mid-kiln (for long dry and wet kilns) to ensure a long conversion time at minimum 850°C.

Persistent organic pollutants and highly chlorinated organic compounds should explicitly and exclusively be introduced at the main burner to ensure complete combustion due to the high destruction and removal temperature of 2000°C and a long retention time (Karstensen, 2006a).

Test burns are recommended for the demonstration of the destruction and removal efficiency (DRE) and the destruction efficiency (DE) of certain principal organic hazardous compounds (POHC) in a cement kiln. The DRE is calculated on the basis of mass of the POHC content fed to the kiln, minus the mass of the remaining POHC content in the stack emissions, divided by the mass of the POHC content within the feed (Karstensen, 2001a and b; Karstensen et al., 2006; Karstensen et al., 2010).

13 Kiln operations, AFR co-processing and

process control

Operating requirements should be developed to specify the acceptable composition of the waste feed, including acceptable variations in the physical and/or chemical properties of the waste. For each waste, the operating requirements should specify acceptable operating limits for feed rates, temperatures, retention time, oxygen etc.

The impact of waste on the total input of circulating volatile elements such as chlorine, sulphur, or alkalis must be assessed carefully prior to acceptance as they may cause operational trouble and clogging in the kiln system. A set of system controls must be in place for an automatic shutdown of the feeding of hazardous AF in the event that any of the following conditions occur (Karstensen et al., 2010):

a) Cement kiln temperatures fall below 1100oC;

b) Conventional raw meal and fuel flow interruption;

c) Kiln speed decrease to below 60 RPH;

d) Oxygen in the kiln exhaust gases less than 1.5%

e) Hazardous waste must not be used during failure of the air pollution control devices. The kiln exhaust gases must be quickly conditioned and cooled to lower than 200°C to avoid the de-novo-synthesis by formation and release of dioxins and other POPs (Karstensen, 2008b);

f) The plant should have an adequate laboratory, with sufficient infrastructure, sampling equipment, instrumentation and test equipment.

Emission and air pollution control must be monitored in order to demonstrate compliance with existing laws, regulations, and agreements. Emission monitoring is also needed for controlling the input of conventional materials and their potential impacts.

14 Cement quality

In the case of perfectly managed co-processing activities, it has been proven that there is no impact to the cement quality when using AR. It is, however, strongly recommended that a quality control and management system be established to guarantee an unimpaired use of cementitious end-products according to all standards, especially for drinking water applications.

15 Potential cost savings

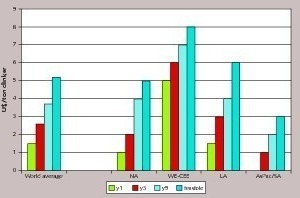

Experiences from more than 40 countries (emerging, in transition and developed), show that net profits from co-processing increases significantly in the first years of implementation (see Fig. 3).

If the conditions discussed in this article are followed, 5 years will normally be required to implement a complete business line for hazardous waste management and handling.

At a global level, a net profit of 5 U$/ ton of clinker can be achieved. Differences in the rate of implementation and net profit are mainly explained by different legal framework and lack of enforcement.

16 Conclusion

A wide range of alternative resources i.e. solid and liquid waste derived fuels, raw materials and organically hazardous waste can be successfully treated and recovered in the cement industry by co-processing.

Alternatives resources co-processing in cement kilns implies complete recovery of energy and valuable raw material components of the waste, i.e. reduction of fossil fuels and virgin raw materials for cement production. This integral method contributes to overall sustainability and reduced GHG-emissions as methane release from uncontrolled dumping as well as CO2 emission by fossil fuels, and saves public funds for building overcapacities of expensive new incinerators. The practice needs, however, to be regulated and monitored by the authorities, like all other waste management activities are. The cement industry should strive to apply the best practices to avoid impacts and, consequently, a bad reputation - one accident may negatively affect the entire industry.

For the cement sector, co-processing of alternatives resources is the only way to obtain long-term sustainability. The key players have proven their capability to anticipate the resources’ scarcity and have developed an alternative resources strategy management as their first priority for long-term sustainability:

Becoming a key player in the local, regional, national waste management strategy.

Moving to services for community and industry.

Integration of all logistic and pre-processing activities.

Providing local environmental solutions.

Keeping and improving their competitiveness and preserving their “right to operate”.

Developing a complete and integral business model, and diversifying its own complete services and products’ portfolio is the only way forward.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.