Laboratory scaling of gypsum board production

The laboratory scale-up process of the production of gypsum boards is the fundamental basis for an efficient formulation development and thus, for the efficient production of high-quality gypsum boards.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

This paper describes a method to link production and laboratory by a continuous characterization of the physical properties during the process of gypsum board production, beginning with a review of the industrial process utilizing a generally common composition of the gypsum board. Due to the fast kinetics of the physical and chemical processes, different measuring tools had to be developed to study the rheological and mechanical properties of gypsum slurries. Conventional methods for mixing, testing of flow and setting time are then considered and compared with continuous characterization tools. Finally, the influence of selected process parameters like mixing intensity and additive formulation are presented.

2 Gypsum board production

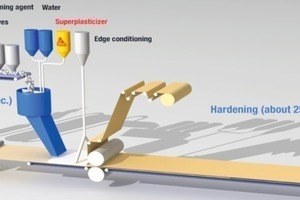

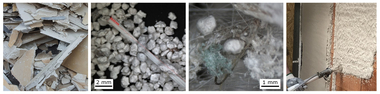

A complex formulation of foam, water, gypsum, but also additives like setting accelerator and plasticizer, is necessary to allow the efficient production of gypsum boards with its technical challenges. One of those challenges is the requirement for adequate fluidity in the initial seconds of processing, followed by rapid hardening and final gypsum board properties such as strength, density and cardboard adhesion.

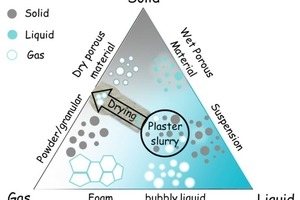

As is generally known, a greater amount of water is required to be added to form a flowable plaster slurry in comparison to the amount needed for the hydration. This has a negative impact on the final product strength. Additionally, higher drying efforts make a crucial contribution to the gypsum board production costs.

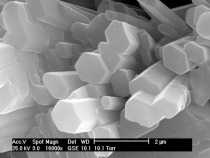

In order to reduce the quantity of excess water, plasticizer is commonly added to generate a certain workability or fluidity of the plaster slurry at lower water content [3]. Various plasticizer technologies exist which all have a different impact on the fluidity, the microstructure development and on the final strength. Special admixtures have been developed for gypsum-based applications [9, 11].

A minimum water content is needed (i) to control the fluidity of the pre-generated foam, (ii) for the chemical reaction, (iii) for the construction of the crystal network and (iv) for the adhesion to the cardboard. The amount of water needed for the fluidity can be reduced with the use of plasticizer or with the modification of the binder. However, to reach the desired board density the reduction of excess water must be compensated by the increase of the foam volume. An example of the effect of water reduction on the increase of foam volume is shown in Table 1. For three different water-binder ratios (W/G), different volumes and masses of main plaster slurry components are listed to produce a gypsum board of a desired final density of 0.8 g/cm3. The chemical expansion is not taken into account.

The reduction of the W/G from 0.8 to 0.6 leads to a 25 % reduction of the water added but also to a foam volume increase of more than 60 %. In addition to these basic physical considerations, the formulation has to be adapted taking the raw material specifications as well as various production process parameters into account. A quantitative characterization of the relevant physical properties is needed to link laboratory and production.

3 From the production to the laboratory: Scaling down

quantification of mechanical properties

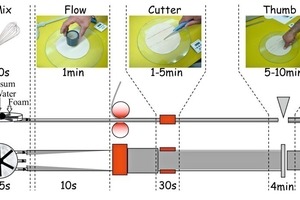

The laboratory tests mentioned principally correlate to the reality of the production except for two limitations: first the precision, as they are performed manually and secondly the kinetics, as it is much slower as compared to the actual production environment. As the rapid production of the gypsum board cannot be easily reproduced in the laboratory, both the formulation and the manufacturing process need to be adapted. Even if the classical tests emulate production, mostly no formulation can be found, which could be directly used in the production.

Alternative test methods exist which allow a continuous and precise characterization of the physical properties of binder slurries. Relatively simple to apply are the semi-adiabatic measurement of the temperature evolution [2] and conductivity [4]. However, these tests are not directly linked to the required physical properties of plaster slurries during setting and hardening. They can be measured i.e. with the Vicat test, ultrasonic measurements [8, 14] but also with classical rheological testing instruments like the rheometer [12, 14].

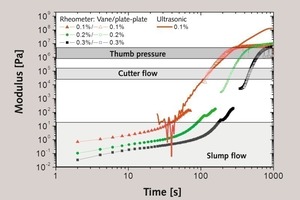

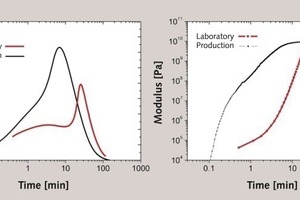

In the following, rheological measurements with an Anton Paar Physica MCR 301 rheometer are described. Due to the fast kinetics of the plaster hydration, a special geometry has been developed to measure the evolution of the shear modulus as a function of time. This geometry allows mixing of the powder with the water so that the evolution of setting and hardening can be analysed immediately after mixing. The powder is poured into the vessel containing the water and additives and mixed for 45 s at a constant shear rate of 500 s‑1. Then the temporal evolution of the stress is recorded with the same cell but in the flow mode, applying a shear rate of 0.01 s-1. At a stress of 200 Pa, the measurement is stopped to prevent damage to the measuring cell as a result of setting of the gypsum binder. To perform higher stress measurements, the use of plate/plate geometry with 10 mm diameter is chosen. A second measurement was performed with the same sample of the plaster slurry which is poured between two plates. The evolution of the complex modulus is recorded while a small shear deformation of 0.005 % is imposed. This plate/plate geometry can be used to measure a shear modulus of up to 2 ∙ 108 Pa. The temporal shear modulus evolution of a plaster slurry (W/G = 0.7) prepared at different plasticizer concentrations versus corresponding slump flow, knife cut and thumb penetration ranges is represented in Figure 4. The figure shows results from an Anton Paar 301 rheometer with two different geometries (vane and plate-plate), a tailored ultrasound instrument and the classical tests. A good correlation between the classical tests and the continuous rheological characterization is found [14].

These measurements demonstrated in an exemplary way the correlation between ‘real’ physical values and classical testing methods. A complete quantitative comparison has already been described in a former paper [14].

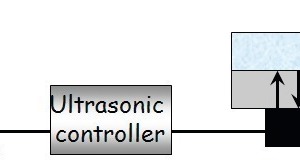

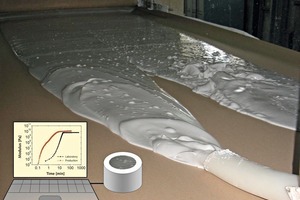

A non-commercial instrument based on ultrasonic technology was developed at Sika Technology [2]. The testing device is schematically represented in Figure 5. It has also been used to follow the evolution of the shear modulus. Measurements made with the ultrasonic instrument and with the rheometer are comparable as can be seen in Figure 4. The ultrasonic technique leads to the same results as obtained with a rheometer but has the advantage of being transportable and easy to use.

As the testing device developed is mobile, it can be used either in the laboratory or at the production site. This allows a direct comparison of the results and a better comprehension of the link between the chemical evolution and the physical properties.

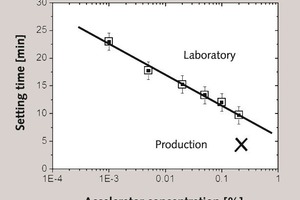

The temperature difference measured in the laboratory is lower than the one recorded in production as the thermal loss over a longer time scale is higher. Further factors must be taken into account to explain the differences observed between production and the laboratory. Those are, on the one hand, mix-design based whereby the final production mix differs from the laboratory-mix by (i) higher accelerator concentration and (ii) additional components like pre-generated foam and starch. On the other hand, process-related differences exist such as different mixing that occurs in a continuous mixer vs. a laboratory batch mixer. The effects of the mixing process and accelerator concentration are described below.

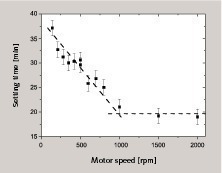

Tests performed in the laboratory are classically carried out with a Hobart mixer or even manually by hand stirring. In the latter case the mixing intensity varies significantly depending on the processor and can therefore lead to strong variations in the obtained setting time. The Hobart mixer gives more representative results but with 500 rpm the mixing speed is considerably different from the mixing intensity of a continuous mixer in a manufacturing environment. The hydration kinetics in the laboratory mix can therefore be linked to production by increasing the mixing intensity. This can be achieved either by increasing the mixing speed or the efficiency of the mixer. The mixing time, however, should be limited to minimize destruction of the newly formed structure. Even taking these aspects into consideration, the result of batch mixing in the laboratory will vary from continuous mixing during gypsum board production.

4 Conclusions

This investigation confirms that the development of a gypsum board formulation is not an easy task; however, it can be simplified by using modern testing methods. The flow and setting properties are closely dependent on the nature of the gypsum raw material and the calcination process. Admixtures are required to regulate the gypsum board production process. For the sometimes widely varying requirements specifically tailored additives need to be developed. A targeting formulation is obtained with a series of lab-tests which mimic the production process as closely as possible. The easy-to-use methods presented allow continuous quantitative characterization of the major chemical and physical material properties. In addition, using these mobile devices, it is possible to reduce the time and effort to scale up from the laboratory to the production by reducing the number of plant trials resulting in significant cost savings.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.