Gypsum plaster made from recycled gypsum

The utilisation of recycled gypsum is becoming even more important with the upcoming loss of FGD gypsum. While RC gypsum (mainly from recycled gypsum plasterboard) is already being used in some cases for plasterboard, its use for other gypsum products is almost unresearched. Research results on a RC gypsum plaster will be presented.

1 Introduction

In recent years, extensive research projects on the recovery of gypsum from construction waste and industrial processes have been initiated in response to the announced coal phaseout and the resulting disappearance of FGD gypsum in Germany. In addition to the fundamental aim of conserving raw materials and resources, protecting the environment and climate, minimising landfill and converting to a more ecological industrial economy, the aim is to increase the recycling rate of gypsum while maintaining the same high raw material requirements [2] and to improve the general...

1 Introduction

In recent years, extensive research projects on the recovery of gypsum from construction waste and industrial processes have been initiated in response to the announced coal phaseout and the resulting disappearance of FGD gypsum in Germany. In addition to the fundamental aim of conserving raw materials and resources, protecting the environment and climate, minimising landfill and converting to a more ecological industrial economy, the aim is to increase the recycling rate of gypsum while maintaining the same high raw material requirements [2] and to improve the general acceptance of recycled building materials. The 2½-year BMWF-WIR! gypsum recycling project “EcoStuc” (Ecological Stucco) [9], which was launched on 1 January 2022, should make a contribution to this.

In the research project “Development of a wall plaster based on recycled gypsum”, MUEG’s recycled gypsum (RC-M; 0/2 mm) with product status [6] was used in comparison with other RC gypsums (RC-Z and -F) to investigate how suitable binders for a lightweight plaster can be produced on a laboratory and in pilot plant scale. The extent to which a complete replacement of the conventional binder made from natural gypsum is possible or whether other approaches are more effective in terms of industrial production and market placement is being investigated. This is done under the condition of achieving comparable properties with a commercially machine-processable product (Ref. WTM or Ref. PGB) and complying with standardised requirements. [7]

To be able to recognise the effect of the RC gypsum, the formulation of the plaster remained unchanged until the investigations into the additive adjustments.

2 Differences between the natural and RC gypsum binders

2.1 Raw materials

The main raw material used for all tests is recycled gypsum from MUEG. It is primarily obtained from recycled plasterboards (GKP). Another RC gypsum from GKP is analysed for comparison. Even with the fulfilment of the TOC value [4], a characteristic influence of this type of RC gypsum is observed. The TOC value is mainly attributed to the cardboard deposits in the form of cellulose fibres (Figure 4) in the micrometre range up to millimetre-sized paper shreds as well as organic substances from paper production (e.g. lignin). Other mineral and/or plastic fibres are present in the microscopic range to a considerable extent (s. lead picture, centre). To be able to attribute the observed differences in properties to the cardboard deposits, another RC gypsum is used. This is an RC gypsum prepared in the laboratory from gypsum moulds, as used in porcelain production. Here are none of the above-mentioned impurities are present because its only made from moulding plaster based on natural gypsum.

The market product, a lightweight plaster, is also made from natural gypsum.

2.2 Analysed RC binder types

In the market product used as reference, the binder corresponds to a multiphase gypsum binder consisting mainly of Bassanite and Anhydrite II. [1,3]

With the focus on achieving the phase composition of the market product, various types of binder were produced from the RC gypsum in the laboratory. They are partly or completely replaced with the original binder of the gypsum plaster.

Firstly, an RC hemihydrate binder (RC-SG) was produced in the low-temperature range. This was used to substitute 16 and 32% of the reference binder. Later, an RC multiphase gypsum binder (RC-MPG) was produced at medium temperatures and an Anhydrite II binder (RC thermal anhydrite, RC-TA) at higher temperatures. Extensive fresh and solid mortar tests were carried out with proportions of RC binder of 20, 50 and 100%.

Table 1 shows the phase compositions by XRD, including the secondary mineral components. The RC hemihydrate binder consist mainly of Bassanite without containing Dihydrate. The multiphase gypsum binder from the recycled gypsum RC-M (MPG-M) consists of approx. 2/3 Bassanite and 1/3 Anhydrite II. This is very comparable with the phase composition of the reference binder produced industrially from natural gypsum and a result of extensive investigations about the best heating regime. The MPG-Z shows with a composition of half Bassanite and half Anhydrite II a higher degree of dehydration with the same regime. The optimised heating regime for RC thermal anhydrite caused a complete conversion into Anhydrite II. The binder was obtained by mixing 20% RC-TA with 80% industrial hemihydrate binder.

The quite high proportion of carbonates or Dolomite in the binders made from recycled gypsum RC-Z is remarkable. That is only half as much in RC-M binders. Both RC gypsum binders contain small amounts of micaceous mica and kaolinite. In contrast, the natural gypsum contains a proportion of magnesite, which is typical for the extraction area.

2.3 Granulometric properties and impurities

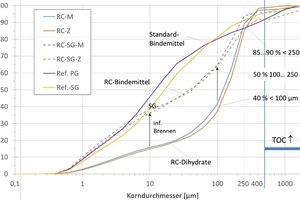

The grain size analysis is intended to show the differences of the RC materials from the natural gypsum binders in terms of their grain size composition. However, it should be noted that the usual evaluation of the laser granulometry of powdery material, which also contains fibrous impurities, leads to a distorted image. The length of the fibres (e.g. cellulose and other fibres) or fibre clusters (see Figure 4) are assumed by the evaluation program to be the diameter of a grain with a rounded shape. In this case, even a few fibre individuals ensure that there appears to be a higher proportion of larger particles than is actually the case (Figure 1).

Figure 2 shows the results of the laser granulometry of the RC gypsum from the company MUEG (M), an RC gypsum from a recycling plant under development (Z), two industrially produced binders made from natural gypsum (Ref.) and the RC binders produced in the laboratory, which in this case correspond to hemihydrate binder (RC-SG). Before being analysed, the materials were sieved at 2000 µm and deagglomerated in an ultrasonic bath with Isopropanol.

For example, approx. 64 V-% of particles of the RC binders (RC-SG) are smaller than 100 µm. For the reference binder, 80 V-% are determined for this.

Furthermore, the significant difference in the grain composition of the RC gypsum and its low-heated binders indicates a relatively high grain decomposition. This means that the porous particles from the gypsum core of the plasterboard partially disintegrate due to the thermal stress. It is also conceivable that the effect of the heat on the fibrous or tangled impurities could have an impact.

Figure 3 shows a sieve analysis of the RC gypsum M. It was determined that around 42 M-% of the material is finer and 58 M-% is coarser than 250 µm. In addition, the TOC value was determined in the obtained three grain classes. This is highest in the coarse grain size range. This is consistent with the apparent observations that remaining cellulose fibres prefer to accumulate in the grainier range.

The presence of cellulose and other fibres in plasters with recycled gypsum from plasterboard is well known. Their influence on odour, colour, porosity, ratio of compressive strength to bending tensile strength and, above all, a significantly higher water demand for comparable workability and a retarded hydration of RC gypsum binders can be determined.

The differential thermal analysis (Fig. 6) also shows the thermally induced decomposition of organic impurities based on the thermal effects and the specific mass losses of a recycled gypsum (predominantly dihydrate) and the thermal anhydrite produced from it (predominantly Anhydrite II and 14 % Bassanite). RC-TA-M has about 2/3 less of these impurities with the selected heating regime (3 h/600 °C).

3 Influence of the percentage and type

of recycled gypsum binder

3.1 Effects on the water demand and the resulting mortar properties

3.1.1 Water demand of the binders

The characteristic water/binder value (W/B) of the pure gypsum binders without additives and admixtures was determined by the “Einstreumenge” (mass of gypsum powder in 100 ml water) that correlates with the BET surface. It provides information on the water demand of the RC binders in comparison to the industrially produced reference binder based on natural gypsum. The results are shown in Table 2. An industrial hemihydrate binder made from the same natural gypsum as the plaster gypsum binder (PGB) is also listed for comparison of the pure RC hemihydrate binders (orange lines).

For example, the W/B value of the RC hemihydrate binders M and Z increases with increasing RC content, whereby small proportions of 16 or 32 M-% RC-SG initially make little difference. It is also noticeable that the pure RC binders require a W/B value of approx. 1, regardless of their type and production temperature. The W/B value of the RC-MPG kt produced on a pilot scale in the factory even exceeds this high value. There are other reasons why even the RC hemihydrate binder from gypsum moulds, which does not contain any cardboard relicts, requires a W/B value of 1. This material is significantly finer than the RC binders made from GKP with a smaller maximum grain size and a higher content of particles < 10 µm. The high fineness and a low content of hygroscopic salts from porcelain production are responsible for the high water demand. The different causes for the water demand of the RC binders have different effects on the workability of the plaster (incl. additives for setting behaviour and workability, filler made of grained limestone and perlites as lightweight aggregate) (Table 4). As no swelling components in the RC-SG-F are responsible for the increased water demand, but rather a pure wetting of the gypsum grain surfaces, the plaster with RC-SG-F has a significantly larger slump after shocking with the same W/F value than the plasters with RC-SG-M and -Z (208 185 mm).

3.1.2 Water demand of RC gypsum plasters

and workability

The water demand of the plasters is reflected in the water/solid ratio (W/F value), which is necessary to achieve a slump of 165 ± 5 mm. The increased water demand of the plaster as a result of the addition of RC material can be recognised on the one hand by the increasing W/F values with comparable consistency (Table 3). On the other hand, this is also shown by the decreasing workability at a constant W/F value of 0.73 in Table 4.

Figure 8 shows the slump as a function of the W/F values for plaster mixtures with different RC binder types in comparison to ready-mixed dry mortar (WTM). The difference between RC-MPG from RC-M and RC-Z is attributed to the lower CaSO4 content and the lower specific surface area because of a higher degree of dehydration of RC-MPG-Z [8]. Possibly a higher proportion of the organic impurities was also decomposed.

The use of 20 % RC-TA results in a water demand comparable to the ready-mixed dry mortar (WTM), which is surprising at first, but the composition of the binder components is noticeably different. Instead of a plaster binder, which is obtained by medium temperatures, a high temperature binder (TA) was mixed with 80 % industrial hemihydrate binder. Although the phase composition is approx. the same as the reference binder (Table 1), the differential thermal analysis (DTA, TG) shows that the impurities in the RC gypsum are largely destroyed at higher temperatures (Figure 6). As a result, the swellable components of the RC material (Figure 4, Figure 5) decrease significantly. In addition, experience has shown that the specific surface area of a thermal anhydrite (TA) is lower than that of a multiphase gypsum binder (MPG).

3.2 Effect on hydration and setting up

3.2.1 Setting times of the binders and plasters

The chemical reaction of the pure binders starts later as the RC material increases, provided the raw material is RC gypsum from recycled plasterboard. In the case of RC gypsum from gypsum moulds, which comes without cardboard deposits, no retardation is observed despite the increased amount of added water. Table 2 shows the start of setting (VB) and end of setting (VE) of the binders, which were determined by knife cut and thumb pressure [1; 5].

Table 5 shows the start of setting of plasters (with Vicat cone according to DIN EN 13279-2 [5]). As the ready-mixed dry mortar proved to be an older material, which also did not fulfil the requirements for the working time of 3 h, a binder (PGB) was produced in the laboratory, which is suitable for comparison. Starting from its setting time of 3 h, the working time was extended from 4 to almost 5.5 and 7.5 h (orange lines) when 20, 50 and 100% RC-MPG-M was substituted.

Initial investigations into possible adjustments to the standard additive combination that affect the setting behaviour have taken place. Table 5 shows examples of three modifications (grey lines). For example, an increased alkaline stimulation by hydrated lime (CL90) and an increase of Dihydrate seeds (DH) already contribute to a significant acceleration. Without the addition of retarders (VZ), the RC plaster with 100% RC material achieves a useful working time (> 50 min) according to the standard, although this does not yet meet the factory specifications.

3.2.2 Reaction behaviour of the binders

and the plasters

From the results of the differential calorimetry of the binders (Figure 10), the retarding influence of components that only occur in RC plaster from recycled plasterboard (GKP) can be clearly deduced. While the hydration behaviour of RC hemihydrate binder from gypsum moulds is comparable to that of hemihydrate binder from natural gypsum, the reaction of RC hemihydrate binder from GKP starts noticeably later and is significantly slower. This is already the case with a substitution of 32 M-%. As can already be seen from the longer time between the start and end of hydration of RC-SG-M and -Z (Table 2), a noticeably longer hydration time is also evident here. All binders were measured with a W/B value of 1 to ensure complete hydration.

The hydration temperature of the plasters (binder + additives + admixtures + lightweight aggregates) is measured in the mortar calorimeter using thermocouples. In each case, 150 ml of fresh plaster with a constant W/F value of 0.80 (Figure 11) or the W/F values from Table 5 (Figure 12) are measured.

The curves of the plasters with 32% substitution with RC hemihydrate binders from GKP recycling in Figure 11 show an approx. one-hour retardation compared to the reference plaster. The deceleration period of the RC plaster is also retarded. It can be assumed that both nucleation and crystallisation rate are affected by the retarding effect.

Figure 12 shows plasters in a different series of measurements with an increasing content of RC multiphase gypsum binder (RC-MPG-M) (modified additive composition compared to the samples in Fig. 11, which contains more retarder). The reduced reactivity with increasing RC content is clearly recognisable. While a 20% substitution still has a small influence, the samples with 50 and 100% substitution show a clearly attenuated, strongly broadened curve with a retarded induction period for hours. Also, the amount of heat is decreasing.

The results of the differential and mortar calorimetry only reflect the hydration of the Bassanite content in the formulation. Anhydrite II hydration does not produce an analysable peak [8]. Determining the degree of hydration could show the retarding effect on Anhydrite II. Quantitative X-ray phase analysis (XRD) can be used to calculate both the total conversion and the A II conversion in dihydrate.

In contrast to the retardation of the pure binders, which is in the range of minutes, the plaster is retarded by hours (see Figure 11 and Figure 12). There is a considerable influence in the presence of the setting-regulating additives. So, it is assumed that the retarding mechanism of the organic impurities has an amplifying effect on the effect of the retarding additives. From a different perspective, the nucleating effect and/or the alkaline stimulation of the accelerators is not sufficient in the presence of RC material from GKP recycling. There are indications of a possible effectiveness of wood ingredients like lignin and a reduced pH value of the pure RC binder agents.

3.3 Density, strength and water retention capacity

Table 6 shows the properties of the fresh and hardened mortar, depending on the type and content of RC binder.

The factory specification of achieving a compressive strength of at least 2 MPa is only reached by the mixtures with 20% substitution with RC-MPG-M (W/F = 0.65) and RC-TA-M (W/F = 0.58). The substitution of 50% RC-MPG-M (W/F = 0.70) is also promising, as there is the potential for minor formulation adjustments. The loss of strength with up to 32% RC-SG tends to be higher despite comparable W/F values.

The higher the RC content, i.e. the higher the proportion of fibrous impurities in the gypsum structure, the better the bending tensile/compressive strength ratio (bBz/bD). The bending tensile strength is increased in relation to the compressive strength. But it can also be seen on the dry-mix mortar (WTM), which was processed with different W/F values, that the compressive strength decreases to a greater extent with increasing water quantity than the flexural tensile strength. Therefore (bBz/bD) also increases with increasing capillary pore content. However, this tendency is not observed in plasters with RC content. Here, the ratio usually remains the same (see W/F values of 0.68 vs. 0.73).

While (bBz/bD) is 0.3 for ready-mixed dry mortar, all mortars with RC gypsum binder content achieve around 0.4 (Table 6). The strengths naturally decrease as the W/F value increases. But even with the same W/F value, the use of RC gypsum binder results in a loss of strength (pink lines). The increased porosity of mortars with RC content is the main reason for this. However, it can also be seen that the compressive strengths of the RC mortars do not correlate with the bulk density or porosity. A varying degree of hydration of the mortar must also be considered. It is more or less depending on the hardening disturbance caused by the organic impurities and is highest with the RC thermal anhydrite substitution. This means that the hardening disruption caused by cardboard relicts is nearly eliminated at the high production temperature of the RC binder.

The water retention capacity (WRV), which should reach at least 97% according to the factory specification, is reached by all plasters. From this point of view, it is not necessary to adjust the dosage of methyl cellulose and/or other stabilising or thickening additives for the present. It is recognisable that the WRV remains unaffected by a degree of substitution of 0.2 but becomes increasingly lower at 0.5 and 1.0. This is primarily attributed to the increasing water content of the fresh plaster mix (with a comparable consistency). It is known that this is accompanied by a decrease in viscosity.

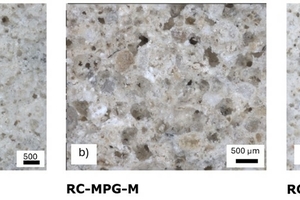

Table 6 also indicates that the higher porosity is not only caused by a higher amount of water when using RC gypsum binders. An increased presence of air pores in the solid mortar can already be recognised by visual inspection. Microscopic images confirm this (Figure 13 a vs. b, c). In addition, the comparison of WTM (W/F = 0.60) with RC-TA (W/F = 0.58) shows an increase in porosity of 4% with a similar W/F value (Table 6 , Figure 13 c), which is attributed to the presence of 20 % RC material. With the same W/F (0.73), the hemihydrate binders made of RC-Gypsum-M and -Z also have a higher porosity and lower density than the hemihydrate binder RC-SG-F without cardboard relicts. It is therefore assumed that the entangled cellulose fibres in particular “trap” air during the mixing process and/or components of the paper adhesives and/or wood ingredients such as lignin contribute to the formation of air voids.

The RC multiphase gypsum binder (RC-MPG M kt) produced on a small scale in the factory also leads to more favourable properties than the RC-MPG-M produced in the laboratory. With the same W/F value, a higher density and strength are determined (green lines in Table 6).

4 Formulation adjustments to achieve

the required compressive strength

Although several causes for the loss of strength when using RC gypsum have been identified, the increased water demand ultimately poses the greatest challenge. Although essential requirements for lightweight plaster can be reached even if the binder is substituted 100% with RC material, the low strength (Table 6) remains a problem that urgently needs to be addressed. Various measures were therefore investigated in the project (Figure 14). As it was found that the cardboard deposits accumulate more in the coarse grain size range (table in Figure 3), it was tested whether the use of RC-MPG-M < 250 µm would lead to a noticeable improvement. This was not the case, so this approach was not pursued further. A far more effective method is to limit the content of RC material to a maximum of 20 M-%. This is shown by the various studies with different degrees of substitution that have already been discussed. However, if a plaster is to be produced using only a recycled gypsum binder, it is worth taking a look at the additives that are used as thickeners and/or stabilisers. In the project, methyl celluloses (MC) were specifically analysed in cooperation with the company DOW. Different MCs were systematically analysed. The use of higher viscosity varieties was successful. Due to the higher effectiveness, a significant reduction in the dosing quantity of MCs was achieved, with high water retention capacity (WRV) and good stability on the wall. The 20 to 40% reduction in methyl cellulose content, depending on the type of MC, allows a significant reduction in the amount of water for sufficient workability. It was found that W/F values ≤ 0.65 always lead to a sufficiently high compressive strength of > 2 MPa. A further effect of the lower MC quantity is a lower retardation effect, which is detectable with all MCs.

MC with greater effectiveness MC dosage ↓ ↓retardation effect MC ↓↓+ water demand ↓ ↓ W/F similar to reference dry-mixed mortar (WTM) ↓ compressive strengths > 2 MPa

Table 7 uses a selection of results to show the effect of the type and dosing quantity of methyl celluloses on the properties of RC plasters in comparison with the reference plaster (WTM) and the formulation with unchanged MC (sample 1).

5 Summary

Various approaches were investigated to partially or completely substitute the binder of a conventional machine-applied lightweight plaster with recycled gypsum binders. To obtain a machine-applicable plaster of equivalent quality after the replacement, which fulfils the factory and normative requirements, a comparable phase composition was aimed for. The binders include usually a similar combination of Bassanite and Anhydrite II. The grain size composition of the RC gypsums differs noticeably from the natural gypsum binder, which is of secondary importance.

To partially or completely substitute the original reference binder, three types of binder were produced from RC gypsum - a hemihydrate binder (RC-SG) to replace mainly the Bassanite component, a multiphase gypsum binder (RC-MPG) for 100% substitution and a thermal anhydrite (RC-TA) to replace the Anhydrite II component.

The type of recycled gypsum is of major importance. The focus of the analyses presented here is on RC gypsum produced by recycling plasterboard waste (GKP). Even if all quality tests are passed, including a TOC value of less than 1, cardboard deposits are still demonstrably present. They are associated with both the visually and microscopically detectable cellulose fibres as well as wood and paper ingredients, such as lignin, which were not explicitly determined here.

Typical properties are changed in plasters and mortars that contain RC binders from recycled plasterboard (GKP). They are not observed when using binders made from RC gypsum, which is obtained from gypsum moulds and comes without cardboard deposits or fibres.

Lower substitutions of 16 or 20% GKP-RC material can be used unproblematically. Although the amount of water usually has to be increased for sufficient workability, very good results are achieved at a practical level. Nevertheless, adjustments to the combination of binder-regulating additives are necessary to counteract the retardation caused by cardboard deposits.

Replacing the Anhydrite II component with RC thermal anhydrite is a promising option. As a result of the higher production temperatures, the cardboard deposits have less effects. The organic impurities were largely decomposed or inactivated due to the temperature. The RC-TA can be replaced by 20% with regard to the phase composition to be achieved. By adding 80% hemihydrate binder (from natural gypsum), a plaster is obtained that does not require an increase in the amount of water. In manual tests, it shows good workability and favourable properties on the wall. There is no more retardation, and the high degree of hydration has a favourable effect on the required compressive strength. This plaster formulation reacts too quickly (VB = 20 min) without adjustment of the corresponding additives and must be retarded.

With 50 or 100% substitution of the RC hemihydrate binder and RC multiphase gypsum binders from GKP, more significant changes in properties become apparent, particularly due to the significantly higher required W/F values, if the plaster formulation is not adjusted accordingly. Mainly, the required compressive strength is not maintained, the stability on the wall is reduced and the curing time is extended by hours. However, despite the relatively high amount of water, sedimentation-stable mixtures are obtained. A complete replacement of the natural gypsum-based binder with RC gypsum is therefore extremely promising. In this regard, various measures were taken in the further course of the project that lead to a reduced water demand and compliance with the processing time of 3 h.

The factory production of an RC multi-phase gypsum binder has already been successfully realised on a pilot scale. Machine processing appears to be unproblematic according to the status. Test walls show promising results.

The various reasons for the reduced strength of RC plaster are summarised below. They apply when using RC plaster made from GKP-RC binders, which are produced with low or medium temperatures.

Influences on the strength of RC gypsum mortars:

Increased capillary porosity due to increased water/solids values (W/F)

Increased porosity due to the introduction of air pores caused by organic impurities (especially cellulose fibre)

Hardening disorders due to the following causes:

Retarded Hydration with simultaneous progressive drying out of wall plasters surface

Reduced degree of hydration

Structural changes due to the influence of organic impurities on crystallisation

CaSO4 content of the RC gypsum (purity or content of other mineral, non-reactive accompanying substances)

The required compressive strength of ≥ 2 MPa was ultimately achieved by selecting other, higher-viscosity methyl celluloses. They are characterised by a higher effectiveness with a lower required dosing quantity. As a result, the necessary workability can be achieved with a small amount of water. Figure 14 provides an overview of the measures that were investigated in the project to reduce the water demand.

7 Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all project partners for their trusting and fruitful collaboration.

The EcoStuc research project “Development of a wall plaster based on recycled gypsum” was funded by the BMBF as part of the WIR! alliance “Gypsum recycling as an opportunity for the southern Harzregion”.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.