Optimization of the thermal

substitution rate – Part 2

By means of MI-CFD modeling, improvements to AFR thermal substitution rates (TSR) can be easily validated. Case study II shows, how natural gas can be replaced by alternative fuels.

Case study II

Case study II

Kiln AFR optimization

The gas temperature profile (Fig. 4) indicates that the highest temperature flame is established in the near burner region (approx. 3.5 IBD or 10 m from the burner tip), which is typically observed in gas-fired cement kiln. The flame lift-off distance is about 0.5 m from the burner tip, which is compatible with the high velocities applied for primary air injection and natural gas. The predicted exit temperature is 1077°C and compares quite well with the plant observed values.

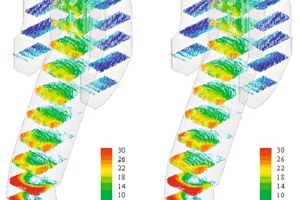

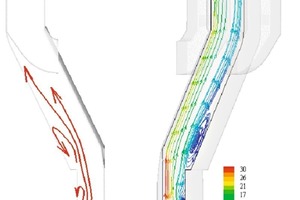

The oxygen profiles (Fig. 5) show good level of mixing between the preheated secondary air and injected natural gas and tallow oil with little evidence of flow stratification between the two streams. The plotted oxygen contours show that the oxygen gradually depletes and mixes fully within 38 m from the burner tip. This is an evidence of good efficiency for natural gas and tallow oil combustion and good level of mixing between fuels and oxygen. Although recirculation zones are observed in the kiln hood and in the burner near region, due to the geometrical effects of the hood, the current tertiary air duct and kiln hood arrangement, however, has little impact on the combustion of the burner fuel. It should be noted that provided plant operates at the average kiln back-end oxygen levels of 3 %, the aerodynamics effects of TAD and kiln hood arrangements would not change dramatically and with little signs of flow stratification at the kiln back-end.

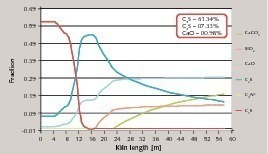

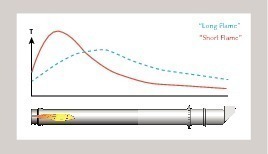

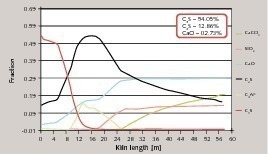

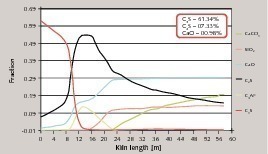

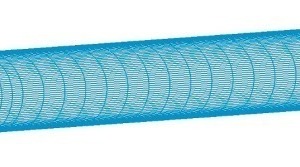

The velocity vector field (Fig. 6) on a vertical plane passing through the centre of the kiln burner shows recirculation zones in the top region of the hood. The recirculation zones are due to the geometrical effects of the hood and it seems not to affect fuel combustion at a significant level. Another recirculation zone is observed at the bottom part of the kiln up to 14 m from the kiln hood back wall. Again the temperature and the oxygen concentration profiles, previously discussed, have no significant effect on combustion of current fuels. Figure 7 shows the bed temperature along the kiln axis as predicted by the clinker model, whereas Figures 8 and 9 show the major species of the formed clinker and the typical short flame of natural gas/tallow as compared with a coal flame emanating from a lower momentum burner.

In general, the current operation by firing natural gas and tallow oil seems to give a good flame short and strong enough for a good C3S content approx. 60 % in the clinker. It should be noted that as per typical temperature profile indicated in the picture above, changes in the flame length will affect the gas phase and material bed temperature profile. Hence it is very important to assess what flame lengths will be achieved by different fuels in order to avoid clinker quality problems.

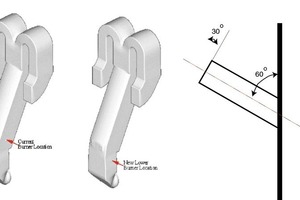

After analysing the base case conditions, further work was carried out to increase the thermal substitution rates of biosolids and SRF, in order to ensure that substitution rates will not affect kiln performance and clinker quality. Biosolids and SRF particles were injected via the main kiln burner as shown in Figure 10. Fuel composition and particle size distribution is given in Table 2.

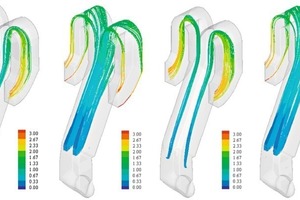

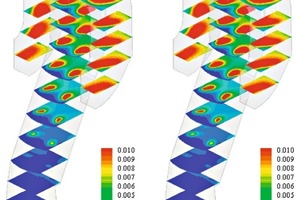

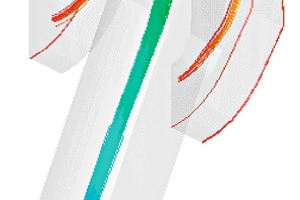

Figure 11 shows particle trajectories of a flame where 90 % TSR was achieved by replacing natural gas. The 90 % are coming from solid recovered fuel (SRF) and biosolids (BS). The change of colour of particles’ trajectories, from blue to red indicates evolution of fuel volatiles, followed by combustion of char (again shown from blue to red). The lighter BS particles stay afloat within the kiln and fully burn in the suspension state whereas the heavier fraction of SRF particles burn up to, on average, 77 % prior to falling on the bed-feed, therefore increasing potential of SO3 cycles.

Several simulations were carried out to investigate a higher TSR of SRF and to suspend its particles for a longer duration in order to increase the particles’ burnout prior to falling on the feed-bed. However, when proportion of solid fuels was increased the flame zone extended as was observed by the depletion of oxygen. It was observed that both SRF and BS particles were injected at about 30 m/s, as compared with very high natural gas velocities of 300 m/s.

Therefore, for higher TSR’s of SRF, the shortfall on burner momentum had to be made up by increasing the burners co-flowing air to a velocity of up to 300 m/s. It was observed that biosolids up to 75 % TSR via the burner with 10 N/MW momentum (via extra primary air momentum) will produce favourable flame conditions for a stable kiln performance. SRF without burner modification will deposit a significant proportion of unburnts into the kiln load. For SRF substitution rates up to 75 %, a higher burner momentum of 10-12 N/MW was required (Fig. 12). Under the conditions shown in Figure 12 , SRF particles burn, on average, slightly more than 90 % prior to falling on the bed, an increase on burnout from 77 to 90 %. The clinker composition of conditions in Figures 11 and 12 are plotted in Figures 13 and 14, respectively.

Summary and comments

Maximising use of petcoke

has a maximum of 15 % volatiles, 50 % of which is methane, and the trend with petcoke from modern refineries is to less than 10 % volatiles,

under reacting conditions, it does not decrepitate like a bituminous coal,

its sulphur level, even at its lowest is about 3.5 % – which is much higher than coal and modern refineries produce petcoke with a sulphur content of more than 6 %,

petcoke can have a Hardgrove Index (HGI) up to 70, however modern refineries are producing 40 or lower, with a high percentage of shot coke, which reduces the real HGI to about 30 as compared with 40-60 of coal,

petcoke can increase the stack NOx by up to 50 %.

Petcoke is difficult to combust and needs to be ground to at least +5 % of 90 μm, with less than 1 % on many occasions.

Higher petcoke TSR needs mill upgrading on most occasions.

High levels of petcoke use produced clinker of at 2 % SO3 which unless the petcoke process is well controlled and the burners and calciners are understood and optimised well and the kiln and calciner can be operated at 3 % O2, big SO3 cycles occur with consequent loss of plant output.

SO3 in the hotmeal has to be no more than twice that in the clinker, i.e., a VF SO3 of 2, with 3 is just tolerable.

The unburnt C in the hot meal has to be less than 0.1 %.

Maximising use of AFR

Even with pre- and co-processing facilities, there are still significant issues associated with the use of AFR and its impact on the process in terms of its impact on output via:

Increased fuel consumption

More water and ash

High levels of O2 needed

For TDF into a calciner it needs to be 100 % less than 50 mms and should not be fired via a burner into the kiln even if it is 100 % less than 30 mms.

SRF into a kiln needs to be mainly 2-D material and 100 % less than 30 mms.

SRF injected into a calciner 100 % less than 50 mms can produce good results, however some plants need 100 % less than 30 mms.

Short term (1 min.) thermal input fluctuations of less than 1 % could be allowed for 100 % TSR whereas for 50 % TSR, max STIF is 2 %, otherwise the plant will need to increase its O2 levels or consequently CO emissions will be increased.

The MI-CFD allows a great insight into what is going on inside the kiln and calciner and allows low CAPEX modifications to be made to really enhance the use of AFR and petcoke at high substituton levels – up to 100 % – of the primary fuel.

It should be noted, however, that the mix of petcoke and AFR is not an easy task, as the unburnt AFR fraction in the hot meal drives the SO3 cycles and build up into orbit, with volatility factor of greater than 10. The heavier the AFR from the burner, if it impinges on the load, it would have a similar impact as the SO3 cycles and build up. However, with the assistance of MI-CFD these negative effects could be minimised.

Acknowledgements

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![3 Illustration of air-through precalciner riser duct [dimensions in mm]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_5a533e48c55d38702fe32207cd2c3b8e/w300_h200_x400_y457_101531240_29637e99db.jpg)

![10 Oxygen concentration [kg/kg] (cut off at 6 % O2)](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_7fb528cfecd12ebd50fbffedf48cf7ed/w300_h200_x400_y400_101531239_645395691d.jpg)

![11 Temperature distribution inside the precalciner riser duct chamber [in C°]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_e0f6fcc794973d28e95a52075d391875/w300_h200_x400_y400_101531272_6e399ef24f.jpg)

![13 Petcoke particles’ residence time in the riser duct (a = Base case, b = extended riser duct with lower burner location) [in sec.]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_e9280f61905551fe6f03de1c3faecd6a/w300_h200_x400_y375_101531187_7672328416.jpg)

![1 Kiln hood, kiln burner and kiln layout [dimensions in mm]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_ca6887baad017751a58d8bd550e704ac/w300_h197_x400_y98_101531249_202a535c89.jpg)

![4 Temperature profile [in °C] (Temperature at oven exit = 1077°C)](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_90926715b671072a528aa2b5a92cbe50/w300_h200_x400_y195_101531203_bbd1208b14.jpg)

![5 Oxygen concentrations [in mass %] (O2 concentration at oven exit = 5,75%)](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_371c1889eee9e73f02d5d908ad9a204e/w300_h200_x400_y148_101531226_42f87cf404.jpg)

![6 Velocity vector field with magnitude [in m/s]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_9861a996685277a7bec5677d653febb9/w300_h200_x400_y204_101531220_6586e8feba.jpg)

![7 Kiln bed temperature along the kiln length [in °C/m]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_176cd7bae7781553c2f344acff02d3fa/w268_h154_x134_y77_101531293_d979615c81.jpg)