Tube mill drive systems – a review

A review of the available literature on the development of tube mill drives is presented in this paper. This presentation includes the motor selection, a mill drive analysis, a failure analysis, the lubrication, the vibration measurement and the finite element analysis, covering strain and fatigue design and a brief write-up on materials and inspection.

1 Introduction

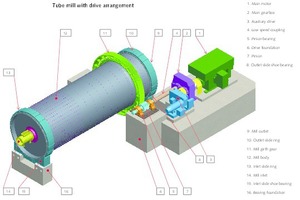

In cement production, tube mills with multi-chambers are traditionally used in either open or closed circuit operations. The process of cement grinding basically includes a grinding mill surrounded by a hoppers feeding system, dust filters, material transport, lifting equipment and cement storage silos for further dispatch in bulk and bag processing.

2 Motor selection

The ball mill is the largest single power consumer in a cement plant. Schachter and Ruesch [1] report that in the process of selecting a suitable motor, there are several issues to consider that, for the purpose of...

1 Introduction

In cement production, tube mills with multi-chambers are traditionally used in either open or closed circuit operations. The process of cement grinding basically includes a grinding mill surrounded by a hoppers feeding system, dust filters, material transport, lifting equipment and cement storage silos for further dispatch in bulk and bag processing.

2 Motor selection

The ball mill is the largest single power consumer in a cement plant. Schachter and Ruesch [1] report that in the process of selecting a suitable motor, there are several issues to consider that, for the purpose of analysis, can be grouped into two distinct categories namely technical analysis and economical analysis.

Schachter and Ruesch [2] also state that it is essential that with such large loads all aspects of the application are subject to evaluations that reflect the best available technology and operating practices, the type of load and its characteristics, the requirements of the motor and power system. Torque ripples produced by standard motors as well as variable speed drive systems are described and compared, together with their interactions with and influences onthe driven mechanical systems examined by Frank [3].

Erdem et al. [4] propose a new approach for the calculation of the power draw of cement grinding ball mills. A new approach based on Morrell’s C model is used to calculate the power draw of dry multi-compartment ball mills. Mill motor choice is greatly dependent on the type of mill gearing system chosen, the power system, primarily the incoming transformer size and its impedance, and the other loads in the plant and the stiffness of the utility’s line. Several approaches for the mill motor choice are discussed by Green and Stroker [5].

Seggewiss et al. [6] review various mill drive configurations and improved synchronous motor characteristics when used with more advanced Current Source Inverter (CSI) drives. This also reviews the different synchronous motor excitation types and resulting performance characteristics with Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) control for new or retrofit installations.

Finley [7] demonstrates the importance of selecting the appropriate operating voltage as well as the benefits of matching fully utilized components. In modern industrial systems it can be shown that there is a great advantage in total cost of ownership to match driven equipment, adjustable frequency drives (AFD), and motors at ratings that fully utilize these components, Fortsch [8] reviews the effects of changing mill filling degree with respect to specific power consumption (kWh/t).

Atmaca and Kanoglu [9] discuss several grinding methods which are available in the cement industry depending upon the material to be ground. In the cement production process, about 26 % of the total electrical power is used in grinding the raw materials (clinker and additives). Rodríguez et al. [10] present a technical evaluation of and practical experience with two different technologies used in high-power grinding mill drives.

3 Mill drive analysis

Grinding mills are used extensively in the mining, cement and minerals processing industries. Diering [11] reports that there is a need to research the design methodology of the drive train components of grinding mills and the analysis of fatigue failures in mills and similar equipment. According to Paul and Schaadt [12], the proper selection of critical drives in a cement plant is of utmost importance as to how well the plant will function over its lifetime. Productivity, efficiency, reliability, longevity, and long-term costs are all affected by the original selection of the equipment and drives.

The investigation by Kress and Hanson [13] focuses on the design concepts of a girth gear from casting through the manufacturing process to final inspection. This article also includes the importance of the installation of the gear set and the operating and maintenance practices during the life of the gear set. Saxer and Heuvel [14] examine girth gear drives which are widely used for ball mills in the cement industry. Two essential factors influence the operating behaviour of girth gear drives, namely the dynamic behaviour of the drive train and the load distribution along the tooth flanks.

Yu et al. [15] discuss the load sharing performance of every pinion, this plays an important role for the fatigue life of gear systems which are driven by a parallel arrangement of multiple pinions. The analysis by Palermo et al. [16] summarizes the dynamic behaviour of geared systems is highly affected by operating conditions which are different from the theoretical case and by deviations of the tooth surface from the perfect involute. Pedersen [17] observes that the bending stress plays a significant role in gear design wherein its magnitude is controlled by the nominal bending stress and the stress concentration due to the geometrical shape.

Shumka [18] describes the use of combined Eddy Current Array (ECA) and Alternating Current Field Measurement (ACFM) to provide a complete survey of all surface breaking indications on the whole gear tooth depth. This method accurately determines the size, length and depth of any cracks found on the surface. The paper by Satter et al. [19] represents a study of the properties of the pinion and the girth gear materials; strength calculation for static loads and surface fatigues, lubrication method; vibration measurements and deflection studies of the ball mill, installation and maintenance methods, etc.

Pedrero et al. [20] investigate how the presence of undercut at the pinion root may affect the load sharing among couples of spur gear teeth in simultaneous contact, as well as the load distribution along the line of contact of helical gears. For ball mills, the study conducted by Zhang, et al. [21] demonstrates in detail the application of the stress-strength distribution interference theory to calculate the reliability of gear transmission, establishes the Kriging model for function fitting, and uses genetic algorithm to globally optimize the volume and reliability of large ball mill gear transmission.

Von Ow and Gerhard [22] describe the method of powering mills such as the AG, SAG and ball mills which have a long and technically interesting history. Frequency converter drive solutions dedicated to single or dual pinion ring-geared mills offer significant advantages over conventional drives due to their application specific features and controls. The procedure of steady-state torsional and dynamic torsional analysis is presented using actual values from an existing plant and its importance as selection criteria of a Twin Drive System for a grinding mill is illustrated by Tost and Frank [23].

The trend to large grinding mills in the cement, mining and related industries with the attendant increase in motor drive horsepower has affected the options for mill drive equipment. Hamdani [24] reviews the more significant aspects and characteristics of the gearless drive (GD), also called wrap-around, and presents some comparisons between the GD and the Twin AC as well as Twin BC drives.

Wurgler [25] writes about the first gearless mill which was put into service in Le Havre/France. For the first time in the history of tube mills the driving motor has been built directly on the mill, i.e., the mill drum is also the motor shaft. In 1969, in the Le Havre cement plant in France the investors were looking at the biggest, and the most advanced technology cement plant. The decision was taken to go ahead with the development of the first gearless mill drives called also wrap-around motor with capacity of 5500 kW.

Symmons and Cockerham [26] present a method for minimising the centre distance of helical gear set of prescribed power capacity using a fixed ratio of face width PCD and formula contained within AGMA (American Gear Manufacturers Association) procedure. The designer may choose to optimize gear trains on the basis of minimum overall centre distance, minimum overall size, minimum gear volume, or other desirable criteria, such as maximum contact or overlap ratios. The method as reported by Prayoonrat and Walton [27] is based on a two-stage optimization procedure. A fault diagnosis system based on discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and artificial neural networks (ANN) was designed to diagnose different types of faults in gears by Akbari et al. [28].

The main objective of the paper presented by Osman and Velex [29] is to study the possible interactions between contact fatigue and dynamic tooth loads on gears. The numerical findings compare well with the experimental evidence from a back-to-back test rig. Three characteristic points on a tooth profile are analysed and it is shown that contact fatigue on spur gears clearly depends on dynamic phenomena. Finally, the introduction of profile relief is discussed and its positive influence on the risk of failures at engagement is emphasised.

Hwang et al. [30] present a paper on contact stress analysis for a pair of mating gears during rotation. Contact stress analyses for spur and helical gears are performed between two gear teeth at different contact positions during rotation. The variation of the contact stress during rotation is compared with the contact stress at the lowest point of single-tooth contact (LPSTC) and the AGMA equation for the contact stress.

Andersen and Oxenbol [31] mention that the selection of drive types is most often based upon economics, considering both the initial investment and the cost of operation. Regardless of the type of drive selected, it is of the utmost importance that the components are well matched to perform faultlessly as a unit. The strength factors in the transmission are dealt with here, as well as an analysis of the contributing loads. How the magnitude of the loads can be determined by analytical methods and by measurements will also be described.

The methods presented by Meimaris and Boughey [32] represent a significant improvement over traditional methods used to analyse mill systems components such as mill foundations and gearless drives. Direct estimates of deflection and vibration levels for the entire grinding system can be obtained. In general, traditional methods provide information on stiffness and natural frequencies from which it is difficult to extract quantitative estimates for stiffness and vibration.

4 Drive failure analysis

Ramamurti, and Omprakash [33] show a detailed investigation into the failure analysis of the heavy duty semi-autogenous grinding mill. The influence of the presence of ribs at the trunnion-end plate junction on the redistribution of stress levels, the effect of centrifugal forces, support conditions and thickness of the major parts of the mill are studied.

The paper by Hamilton et al. [34] summarise the investigations into some of the failures of shafts, bearing housings, girth gears, gearboxes and motors. The behaviour of the electrical starting circuit, the design criteria for the mechanical components, the dynamic response of the drive train and manu-facturing quality have all negatively influenced drive train reliability.

Kosec et al. [35] describe a case where the pinion from the drive of the cement mill failed when the teeth cracked and spall occurred on the sides of several teeth. The authors have found that the failure of the pinion is a direct consequence of the incorrect geometry of the surface hardened layer. In the paper by Netpu and Srichandr [36] the results of the failure analysis of a helical gear used in a power plant in Thailand is reported. The results showed that the fracture surface exhibited fatigue fracture characteristics. There were inclusions in the microstructure of the gear material.

Chen and Shao [37] derive a mesh stiffness model of an internal gear pair with a tooth root crack in the ring gear based on the potential energy principle. The simulated results show that bigger reduction in mesh stiffness is caused by the growth in the crack size.

The purpose of Desir [38] is to explain the reasons for failure, justify the arrived solution, and give economic information about some of the repairs already made.

Domazet et al. [39] present some typical fatigue damage in industry and transport. The complete damage analysis (numerical and/or experimental stress distribution evaluation, fractography, assessment of remaining service life, etc.) showed that design errors have caused all of these, and many other cracks and failures.

5 Mill drive lubrication

A lubricated impact analysis between the teeth is introduced in the study by Guilbault et al. [40] for the minimum film thickness calculation during contact losses. The dynamic transmission error (DTE) obtained from the final model showed close agreement with experimental measurements available in the literature. The nonlinear damping ratio calculated at different mesh frequencies and torque amplitudes presented average values between 5.3 % and 8 %, which is comparable to the constant 8 % ratio used in published numerical simulations of an equivalent gear pair.

Colombo [41] presents a detailed investigation of the modified FZG test method for determining the ability of an open gear lubricant to protect large open gears in mining environments, EHD calculations that are used to determine the minimum viscosity of a lubricant base-fluid that is required to protect large open gear drives, the environmental issues that challenge the manufacturer of open gear lubricants and their subsequent use and handling. Kress [42] reports that the maintenance of girth gears, lubrication of girth gears is the key to their long life and is covered.

Barrett [43] finds out that since the enactment of environmental regulations in North America and other regions of the world affecting the use of chlorinated solvents, and the disposal of used lubricants, the practice of lubricating heavy-duty open gear drives has been in a state of evolution. One result of these changes is the proliferation of new lubricants professing to be environmentally more acceptable. This, in turn, has burdened gear manufacturers with the need to sanction the use of lubricants which exhibit non-traditional physical and performance characteristics.

6 Vibration measurement

A spectral analysis of the electrical power draw of the two 5,2 MW motors driving a large grinding mill was performed by Lines and Warner [44] to determine whether they are the source of a severe 55,8 Hz vibration. This shows that the motors do not supply the mechanical system with any average power to cause the vibration. Vibration problems in induction motors can be extremely frustrating and may lead to greatly reduced reliability. By utilizing the proper data collection and analysis techniques, the true source of the vibration can be discovered as illustrated by Finley [45].

There have been numerous incidences involving harmonic wear in drive trains in auto-sag mills. According to Fenton [46] this wear is related to transient and steady state vibrations which can lead to the following forms of failure: heavy wear on gear and pinions, cracked teeth, pinion bearing failure, gearbox and clutch frame failures. Twin drives are more sensitive to lateral vibrations, due to the nature of the forces causing relative motion of the drive piers. Misalignment of the gear and pinion can cause stress concentrations in the teeth in the gear-pinion mesh – leading to overloads, spalling, harmonic wear and torque oscillations in the drive train by Fenton [47].

Szczepanik [48] conducted pinion pitch measurement and vibration analysis to find a relationship between vibration signals and the errors. Analysis of time synchronous averaging (TSA) indicates the teeth with pitch error. TSA and sideband index (measure of sidebands in spectrum) allows the first estimation of the pinion quality. The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) is widely used for analyzing non-stationary vibration signals from rotating machines and in order to understand the defect signature appropriately, the concept of adaptive wavelet design and its implementation for defect identification are discussed. Mayer et al. [49] vibration problems which occur after some considerable period of operation are often solved by simply replacing or repairing worm system components.

In the case of a tumbling mill, a rotating system, the natural frequency of a given mill, as seen by a stationary observer, is also a function of the rotation speed. The consequence for a rotating mill, and for that matter any rotating system, is that if the natural frequency of the mill should happen to match the operating rotating speed of the mill, resonance of the mill will occur. The objective of the paper by Radziszewski and Quan [50] is to explore the effect of mill diameter, length and speed on mill natural frequencies.

The Flender service has developed solutions for condition monitoring which are not only suitable for monitoring machines and processes but also for condition diagnosis with subsequent conditions-oriented maintenance. Becker and Cools [51] describe the individual development steps in conditions monitoring using the example of girth gear units, and explains the reasons why the drive specialist has developed VibController and GearController using internet technology.

7 Finite element analysis

An approach for mesh generation of gear drives at any meshing position is presented by Lin et al. [52]. The dynamic responses of the gear drives are obtained under the conditions of both the initial speed and the sudden load being applied. The influence of the backlash on the impact characteristics of the meshing teeth is analysed. Celik [53] presents the boundary element method with the constant and isoperimetric quadratic element which was used to compute the teeth deflection and stresses, respectively. The numerical outputs demonstrate that the isoperimetric quadratic element should be preferred to the general machine element, of which the gears are representatives.

In the paper by Arikan and Kaftanoglu [54] dynamic loads on spur gears are calculated by using an analytical model based on torsional vibrations of gears and dynamic load variations during a mesh cycle of a tooth are determined. Variable stiffness of gear teeth, which are required for dynamic load calculations, and tooth root stresses resulting from dynamic loads are found by using the finite el-ement method. The elastic deflection of gear teeth is analyzed by Park and Yoo [55] to investigate the deformation overlap. The deformation overlap, which is a numerically calculated quantity through displacement analysis at the initial contact, is defined as the piled region of a contact tooth pair due to the elastic deformation.

Rao and Muthuveerappan [56] explain about the geometry of helical gears by simple mathematical equations, the load distribution for various positions of the contact line and the stress analysis of helical gears using the three-dimensional finite element method. In the study conducted by Nalluveettil and Muthuveerappan [57], an isoparametric brick element is used for finite element analysis. The stress distribution obtained at the root of the tooth is compared with the experimental results available in the literature and the tooth behaviour at the root is studied by changing the various parameters such as torque, pressure angle, shaft angle, rim thickness and face width of the gear pair.

Ramamurti, and Rao [58] present a new approach to the stress analysis of spur gear teeth using the finite element method and cyclic symmetry. Each tooth is considered as an identical substructure of the gear wheel. Frequency analysis is carried out using a simultaneous iteration scheme to solve the eigenvalue problem. The findings of the three-dimensional stress analysis of spur and bevel gear teeth by the finite element method using the cyclic symmetry concept. The natural frequencies and mode shapes are obtained using the sub-matrices elimination scheme. This efficient approach can also be used in the dynamic analysis of gear tooth utilising the geometrical periodicity and the sub-matrices elimination scheme were presented by Ramamurti et al. [59].

Casanova el at. [60] find out that the face load factor is a common coefficient used in gear design standards that takes into account the uneven distribution of load across the face width of the gears caused by the mesh misalignment. The results obtained from the application of finite element analysis to this model are compared with those obtained from application of the ISO Standard 6336 coefficient-based method (Method C).

The optimization of the asymmetric spur gear drive is carried out using an iterative procedure on the calculated maximum fillet stresses through FEM and comparisons have also been made successfully with the results of the AGMA and the ISO codes for symmetric gears to justify the results of the finite element method pertaining to the study conducted by Senthil Kumar et al. [61]. A new numerical procedure of solution has been developed by Sfakiotakis and Anifantis [62] for the study of stress singularities in gear teeth fractures incorporating kinematic rotations and varying contact conditions.

Cleary [63] analyses the charge motion, short term ball segregation processes and energy utilisation in a 4 m diameter cement ball mill using the Discrete Element Method (DEM). Three-dimensional finite element modeling and analysis of the mill were performed by Mirzaei et al. [64] under various loadings including: charge weight, dynamic loading due to the charge motion, centrifugal forces imposed by partial rotation of the charge, and the driving force imposed by the pinion. DEM is a proven numerical technique for modelling the multi-body collision behavior of particulate systems. In the study by Mishra and Rajamani [65], all the parameters are carefully determined experimentally for different operating mill conditions.

The experimental values from DEM were compared with the simulated data using different charge lifters and charge levels by Alonso and Delgadillo [66]. The DEM simulation clearly shows that the velocity charge changes with a modification of the lifter profile. Ning et al. [67] focussed on studying the dynamic state of a 600 x 900 mm laboratory ball milling added vibrating. They presented a new approach via finite element analysis to analyse the effect of the cylinder with alternative load. Then, the shell’s stress and strain can be obtained under the above two loads.

Datta and Rajamani [68], describe the design and scale-up of ball mills which are important issues in the mineral processing industry. A batch-grinding model using the impact energy distribution of the mill is explained. The distribution of impact energy is obtained from the simulation of the charge motion using the discrete element method. The model is also verified with experimental data, and the strengths and the weaknesses of the model in its current form have been identified.

Ramamurti et al. [69] report the finding on the dynamic response of cement mills due to the random loading of the moving cylpebs. Input dynamic pressure inside the mill has been estimated based on experiments conducted on model mills. Cyclic symmetric approach in conjunction with the random vibration theory has been used as the tool for the analysis. The study covers the full range of cement mills. The limitations of the approach are also presented.

8 Experimental analysis

Meimaris and Lai [70] investigate the stress ranges from strain gauge measurements and are compared with those calculated using finite element models for two mills. For lower total charge to ball charge ratios, the pressure on the heads or end walls of the mills reduces dramatically. As this ratio increases, the pressure on the heads increases to approach a hydrostatic load. Ramamurti et al. [71] describe a method of computing stresses on a grinding mill due to freely falling balls which has been presented using finite element analysis and a semi-analytical approach. The reliability of the results obtained has been demonstrated by comparing it with experimental data available on an industrial mill of 3.8 m diameter.

Ramamurti et al. [72] analyses the stress distributions of end mills in cement plants by means of the finite element method. The present approach is semi-analytic in nature reducing the three dimensional problem to a two dimensional one. The mill is taken as rotationally symmetric. Ramamurti and Sujatha [73] report the finding of exhaustive experimental work carried out on the model of a ball mill. The quantities measured were the dynamic pressure on the shell due to the resulting dynamic strains. This study was conducted using the operation speed, size of the steel balls (charge) and the weight of charge inside as parameters.

In the paper by Govender et al. [74] a methodology for characterising shear rate profiles in tumbling mills based on in situ trajectory fields from Positron Emission Particle Tracking (PEPT) experiments is presented. Cleary [75] describes in his paper the ongoing need to improve the efficiency and performance of grinding mills requires more detailed understanding of the dynamics of the charge behaviour. The Discrete Element Method (DEM) for simulating the flow of granular materials is increasingly used to model such mills in order to extend this understanding.

9 Fatigue design of mills and internals

Meimaris and Lai [76] calculated the stress ranges for eight mills and compared them with allowable stress ranges from published fatigue- design codes. It was concluded that mills do not represent a unique class of structure that require industry-specific analytic approaches and assessment standards. The stresses in mills can be analysed accurately using the finite element method and modern fatigue design codes and methods.

Thompson [77] discusses the analytical methods available for use in the design of large semi-auto-genous grinding mills through a review of techniques employed in some of Boliden Allis’s most recent projects. Topics covered include structural evaluations for fatigue purposes, seismic analyses for regions of high seismicity, analysis of bolted joints and fluid film bearings, as well as particular analyses required in the design of mills powered by means of wrap-around motor.

In the course of past years, some sources in the grinding mill industry started promoting further changes in the allowable stress values used in grinding mill design. The paper by Svalbonas and Ficklin [78] covers that history, starting with the author’s involvement in early 1976 and concluding with a comparison to 20-35 year old operating mill performance.

Sutherland and Anbari [79] present the successful testing of a new high efficiency indirect cooling technology in a cement milling application. Conventional cement cooling uses water flow that is open to the plant environment leading to issues with efficiency, maintenance, emissions and contamination. A new indirect cooling technology using cooling water enclosed within plates was tested at a Canadian cement plant showing improved efficiency and promises better maintenance and water usage. Test results are summarized and compared to the conventional cement cooling equipment.

10 Materials and inspection method

Hall et al. [80] report that in response to an increasing number of failures of cast steel girth gears on grinding mills around the world, Hofmann Engineering has developed technology to fabricate interchangeable replacement girth gears from high purity steel forgings to quality levels which meet AGMA Grade-2. Replacement fabricated gears have been supplied for SAG mills from 6 to 9 meter diameter. As the cost of forged fabricated gears has now become competitive with cast steel gears, new-build green field projects with SAG mills up to 8 m diameter have specified forged fabricated gears for new SAG mills and for their attendant ball mills.

Recent manufacturing advances for both girth gears and pinions have significantly increased the power density of gearing used on grinding mills. These advances include new materials which increase the hardness of girth gears, precision machinery to cut large diameter girth gears, carburizing of large diameter pinions, and tooth modifications finish ground into coarse pitch pinions. The combination of these technologies now allows girth gearing to transmit up to 10 megawatts per mesh and wrap-around 10 meter diameter mill shells were presented by Hankes [81].

Shumka [82] describes a two-part, new proposed standard for electromagnetic method for preparation and examination of gear teeth in the cement sector on kiln and ball mill girth gear drives, including pinions-particularly on the addendum, and root area. This practice addresses the need to detect surface breaking flaws electronically and to have the ability to accurately size any surface breaking cracks found on the cast forged kiln or ball mill girth and pinion teeth faster and more effectively than other methods.

A systematic experimental evaluation of austempered ductile iron (ADI) as a gear material was undertaken by Martins et al. [83]. The evaluation of this ADI as a gear material concerns two main aspects: power loss and contact fatigue resistance (pitting and micro pitting). All gear tests were performed on the FZG test rig. For the micro-pitting and power loss evaluation two gear lubricants were considered. The results show that ADI is a material to be considered by gear designers, once the energetic behavior of ADI gears is similar to carburizing gears, being although slightly worse at high input power.

Karpuschewski et al. [84] show the testing of finished gears in industrial production with a non-destructive, ecological and micro-magnetic method called Barkhausen noise analysis. The strength of Barkhausen signal is influenced by the elastic stresses and the micro structure. So, changes in residual stresses and material structure are measurable.

11 Conclusion

The paper has given a detailed literature research overview about the tube mill drive system. Extensive use of FEM has enabled improvement in the design of mills on scientific lines, the experiments carried out by various investigators have indicated the efficacy of the analytical solution. It also presents inadequacies in the mill drives. This probably can be attributed to sudden variations in loading conditions, variations in the environment and lack of quality of manufacturing.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.