Trends in the performance management

of cement plants

Benchmarking the performance of cement plants is the trend in the global cement industry and is now widely used. The following article outlines the major implications and focus areas of this approach.

1 Introduction

Cement plants are operating continuously for 24 hours a day and when possible for about 330 days a year without interruption. The rest of the year the plants have their annual shutdown for major repairs. Each day of unscheduled shutdown results in a loss of income, which can be as high as 0.3 million US$ for a standard 1.0 million tons (Mta) capacity plant and cement prices in the range of 100 US$/t. Accordingly plant managers have to concentrate on keeping the plant running and optimising the production costs. These production costs differ greatly depending on region, plant...

1 Introduction

Cement plants are operating continuously for 24 hours a day and when possible for about 330 days a year without interruption. The rest of the year the plants have their annual shutdown for major repairs. Each day of unscheduled shutdown results in a loss of income, which can be as high as 0.3 million US$ for a standard 1.0 million tons (Mta) capacity plant and cement prices in the range of 100 US$/t. Accordingly plant managers have to concentrate on keeping the plant running and optimising the production costs. These production costs differ greatly depending on region, plant technology and other parameters but are the most useful benchmarking parameter for the comparison of individual plants [1].

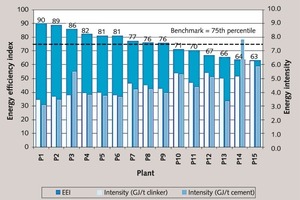

For several years this kind of benchmarking has been used by a number of cement manufacturers, engineering consultants and organisations mainly for cost and energy efficiency comparisons. For example the Cement Association of Canada (CAC) used this method to compare the specific thermal energy demand of Canadian cement plants (Fig. 1). With support from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), the CAC commissioned the benchmarking study of Canada’s Portland grey cement industry in 2007. The study determined that the overall energy efficiency of the 15 plants was relatively good, with a median energy efficiency index (EEI) of 76, compared with a theoretical best practice plant value of 100 [2].

In an international benchmark comparison the Canadian cement plants will most likely be at the lower end, because the average energy demand of the plants was 4.2 GJ/t of cement and 4.5 GJ/t of clinker, when compared with 3.0 GJ/t of clinker or less, which is possible today with modern plants. Accordingly when using benchmark methods for the comparison of actual cement production costs it will be best if the latest energy and other production costs of other cement plants in the same region are known. If not, average cost breakdowns could help. The average Lafarge 2012 production cost for cement is (before distribution and administration): 33 % energy, 29 % for raw materials and consum-ables, 26 % other costs and 12 % depreciation.

The benchmarking of cement plants should take into account that each plant is unique in terms of its raw materials, fuel types and cements produced, beside plant capacity, technology used and the status of the plant (age, condition, automation), management and human resources. So for example with an advanced control and automation system the plant can be run much more smoothly with a stable kiln condition at lower burning zone temperatures which can result in reducing fuel consumption by up to 5 %.

2 Performance management and benchmarking

In the last decade cement kiln lines became larger because of the economies of scale that can be achieved with high capacity plants. Globally there are more than 20 additional kiln lines operating today with a capacity of 10 000 tpd or more, compared to 10 years ago. Beside the very large plants there is a trend for kiln capacities in the capacity range of 5000 to 6000 tpd [3]. Nevertheless the drawback of this approach is that if these kilns are not run close to optimum, the losses are bigger than with small plants. When the benefits of the economies of scale shrink it becomes more difficult to achieve the desired return on plant investment. So with larger plants the needs of optimization significantly increase.

In larger cement groups auditing has become a part of the normal routine of performance management in cement plants and individual kiln lines. A professional plant audit is a powerful tool in analyzing current plant performance, identifying current limitations on the productivity of the plant, developing improvement measures and eventually justifying necessary modernizations and plant upgrades. When the audit is properly conducted the cost drivers that have the greatest influence on the profitability of the plant can also be identified. Other performance indicators include training, environmental issues and occupational health & safety (OH&S).

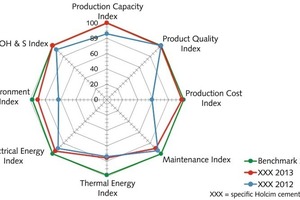

Figure 2 shows an example of the overall performance index of a cement plant, benchmarked against other plants [4]. The benchmark index is given as 100 for each parameter and includes aspects such as production capacity, product quality, thermal energy, electrical energy, production, maintenance costs and OH&S. While the rated production capacity of the kiln is mostly indexed at 100, the thermal energy consumption index can be 3.0 GJ/t of clinker and the electricity demand index can be 100 kWh/t of cement. More specifically the indexes can also be based on the best practices which are possible for a specific kiln size [5].

In the example on the chart the plant was able to keep or improve its performance in practically all aspects close to the benchmark from one year to the other, with the one exception of the maintenance index. The decrease in the maintenance index indicates that with better or higher maintenance the targeted high production capacity and lower production costs could be achieved. In thermal energy consumption, only a small effect can be seen. Thermal energy consumption is fixed with the plant design and the type of pyroprocessing system (Fig. 3). It is also interesting to note that the cement quality was not compromised.

In practice if cement plants (Fig. 4) want to start with a performance audit, normally a longer time span is necessary to achieve significant improvements. Such an audit begins with a historic evaluation of plant operation and stoppage data being collected for the past two or more years. Data for fuel consumption, power consumption, output and product quality will also be analyzed. In a more detailed analysis, the frequency, durations and reasons for kiln stoppages will be analyzed and categorized (mechanical, electrical, refractory, instrumentation/plant control, environmental, human errors, etc.) in order to identify performance gaps in key technical or other areas.

From such an analysis the potential for plant performance improvements can be derived. Making adjustments or improvements to the plant operation often needs only a little capital investment but issues such as operator training and fixed operation procedures are very important. If it comes to a de-bottlenecking of the plant or the upgrade/ modernization of single equipment usually minor capital investments with a payback time of < 24 months are necessary. For an upgrade of the preheater, kiln and cooler system or new cement grinding equipment (Fig. 5) or new storage and dispatch facilities, major capital investments with 3-5 years payback can be feasible.

3 Process optimisation and production consistency

The performance of a cement plant depends on a large number of parameters. An optimization of the plant’s throughput must not be the energy optimum or vice versa. And there are a lot of other parameters, which could have their own optimum, such as the cement quality, maximum availability, maximum use of alternative fuels, lowest maintenance or the environmental impact of the plant at the rated or other given capacity. Furthermore an individual optimization can be achieved for the different plant sections from quarry to cement distribution. It is important to find the right mix.

Another important point is that kiln lines tend to become unstable or unbalanced over time. When the plant is commissioned and the guarantee parameters are fulfilled the individual set points for the plant are installed. But when the plant ages, the raw material composition changes, the fuel changes and mills throughputs or fineness change due to wear and the set points have to be adjusted. If for example the fineness of the raw material has to be reduced due to throughput constraints, then the fuel consumption of the kiln will increase. Empirical studies show that each additional 1 % residue of raw material fineness above the target of 12 % on the 90 µm screen will result in 5-10 extra kcal/t clinker in fuel demand [6].

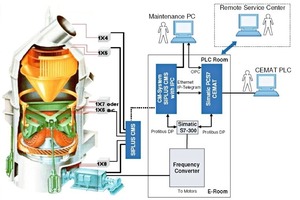

In a modern dry processing cement plant there are a large number of inter-relationships in the many process parameters. Without a good understanding of the different processes it will become difficult to adequately optimize the cement production process. Today, various expert systems are available which are specifically designed for cement plants and supplement advanced automation and control systems of the cement plant from the central control room (Fig. 6). The expert system’s approach is to model the behaviour of the best kiln operators by means of neural networks, soft sensors and model predictive control (MPC). MPC aims to integrate “self-learning” and “auto-adjusting” modules [7].

MPC systems have become especially useful for cement mill control. There are many plants in Europe where mills have to be operated when there are low electricity tariffs and at least a daily start-up and shutdown becomes necessary. So for night shift operations, which have a reduced staff level, the MPC shortens the mill start-up phase and allows the mill to be operated at stable conditions. Such systems require comprehensive and reliable instrumentation (Fig. 7), including, for example, vibration sensors for the mill. When MPC systems are used for kiln control, it is very important that process alarms are carefully monitored, because any drift to extreme or dangerous conditions has to be avoided.

The biggest challenge for a cement plant compared with a specific chemical plant is that the raw materials differ widely and the production of constant quality cement needs several stages of blending and homogenization in the process flow.

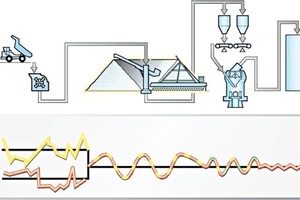

Figure 8 illustrates the complexity of the raw material variation. The first step is to employ a blending bed to even out the quality fluctuations in raw materials coming from the quarry. Other components are added in the raw mill in order to attain the constant cement moduli for the burning process. Complete homogenization takes place in the raw meal blending silo.

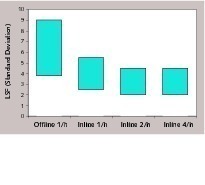

The control system for the material handling starting with the receipt of raw material from the quarry to the kiln feed has to be designed to achieve the required level of material homogeneity. Figure 9 shows the qualitative result for the fluctuation in lime standard arising from the raw meal analysis method. The greatest range of fluctuation occurs in offline operation with manual sampling. In the case of inline operation with automatic sampling and automatic sample preparation there is only slight fluctuation that also depends on the number of samples per hour. More than two samples per hour bring no further improvement [8].

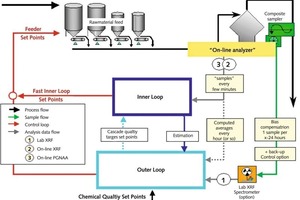

The best means of achieving process optimization is generally a combination of online and inline analysis with two control loops. As depicted in Figure 10, for the raw meal analysis the inner control loop is formed by an online analysis and the belt feed material is used as the manipulated variable. The outer control loop consists of inline laboratory analysis. Such a configuration can be used for the implementation of various cascade solutions, which can also include the raw meal blending silo to achieve an optimal raw meal consistency. However, such methods also involve a significant increase in the amount of equipment and the complexity of the control system.

4 Maintenance strategies

In a cement plant which is continuously operating not all components are necessarily running for 24 hours a day as is the case for the pyroprocessing equipment. There are some buffer functions, for example, in the raw material processing and clinker storage, which allow the raw material handling system or the cement grinding system to be active for only 8 hours a day. Accordingly some cement plants have such high clinker storage and cement storage volumes that they can even produce and sell cements when the pyroprocessing line is in the annual shutdown.

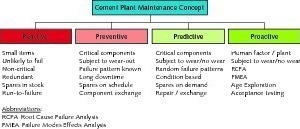

So, “critical” equipment which is running around the clock needs different maintenance criteria than “non-critical” equipment which runs for 8 hours. In many cement plants the maintenance concept for the latter equipment is reactive or “as needed”, while for the critical equipment more proactive tools such as predictive and preventive maintenance are used. Figure 11 gives an idea of how the concept is applied to cement plants, with measures that can be installed in parallel, depending on how critical the equipment is. The measures adopted will depend on the cement producer’s philosophy, the age of the plant and budget constraints.

Reactive or corrective maintenance allows the plant sections or components to operate until a fault or equipment failure occurs. These faults can usually be solved or repaired without requiring a plant stoppage. The situation is different in the case of critical components like large drive motors, large bearings for mills and gear units. To avoid the replacement of such components before they reach the end of their planned service life, the condition of the units is monitored. Condition monitoring can be implemented by recording different parameters and interpreting them in order to assess the possibility of failure.

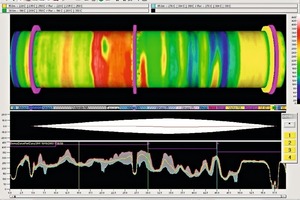

In recent years condition monitoring has experienced a real boom, due to the advance in automation solutions. Condition monitoring of plant components is supported by active maintenance concepts that are aimed at identifying fault mechanisms and consequential damage and determining the possible effects of, for example, operating errors or incorrect maintenance. One of the most widely established processes in the cement industry is computer-aided thermal imaging of rotary kilns. The latest processes make use of infrared sensors that scan the entire length of the kiln and supply three-dimensional pictures and evaluations (Fig. 13).

Preventive maintenance is primarily employed for critical plant components that involve lengthy stoppages. It comprises a planned maintenance programme and regular inspections (Fig. 12) to ensure high availability of the respective plant components. The inspection results determine whether the required maintenance can be carried out during the annual plant stoppage or need to be performed earlier. This particularly serves the purpose of avoiding expensive scheduled replacement of systems and equipment that are still in fully functional condition and have a lengthy residual service life expectation.

Preventive maintenance is essential to minimize the number of unplanned plant shutdowns. Shutdowns are always problematic because of the length of time involved and have a decisive effect on the cost-effectiveness of the plant. The maintenance concept is simple: solve problems before they happen. These requirements are met by inspecting critical plant components, such as the kiln, cooler, mills, large fans etc. to determine how smoothly the machines are running, whether vibrations or high surface temperatures occur, whether there is corrosion etc., and by checking oil levels and lubricant conditions. Another purpose of regular inspections is to check that all plant safety issues are assured.

In the last few years computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS) have been more widely accepted and established in the cement industry. These systems are based on predictive and proactive tools and are a major part of the so-called reliability centred maintenance programs. CMMS use sophisticated failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) and root cause failure analysis (RCFA) tools. So for example the RCFA is used to conduct an investigation into every kiln stoppage in order to find out and determine the true cause of failure and to prevent the same problem occurring in the future [9].

5 Outsourcing

In Africa, the Middle East and Asia there is a clear trend to outsource plant operation and maintenance (O&M) as well as other services such as performance audits. Probably the market leader in the sector is FLSmidth (FLS), who were awarded almost 10 O&M contracts in the last few years (Table 1). In such projects FLS is contracted to operate and maintain the cement kiln line or plant over a specific period of time such as 5-7 years. FLS guarantees a specific cement output of the plant for an agreed price per ton. The fee of the O&M services are performance based and FLS is committed not only to operating the plant efficiently, but to maintaining it in premium condition.

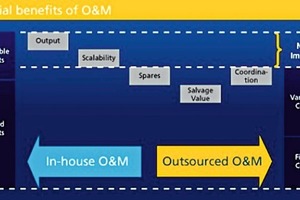

The benefit for the cement plant owner of this kind of outsourcing is that the fixed production costs are significantly reduced, while variable (performance based) costs will probably increase and at the end there is a net and significant saving in costs (Fig. 14). Such an approach is especially useful for new investors and cement plant owners who have a problem finding experienced personal to operate and maintain the plant. Furthermore for the plant owner the risk of operating a plant is reduced, because the service provider takes the risk. Plant owners keep the responsibility for the raw material, utilities, offices, security and plant property.

At the moment in the cement industry there are a handful of providers for O&M contracts including engineering consultants such as Holtec Consulting in India and Cemex Global Solutions. Other services such as those offered by ASEC Cement in Egypt include an investment in the plant which can be a minor or major stake in the plant assets. So the full spectrum of contracts which are possible today include:

BOT models, this is the build, operate and transfer concept as known by other industries such as power plants and other utilities, sometimes referred to as DBO (Design, build, operate with later transfer).

BOO models (Build, Own, Operate) according to ASEC approach.

DUO/DDO models (Design, upgrade, operate and Due diligence, operate), such as the one offered by FLS for older plants requiring an upgrade or performance optimisation.

It should be noted that some of the cement majors also provide O&M services to internal and external customers. TECHPORT for instance is a Holcim Group company that is looking at developing a synergistic collaboration among Holcim and Indian group companies ACC and ACL. At the moment the primary objective is to contribute to the performance improvement of ACC and ACL plants. Cemex Global Solutions also has experience in practically all O&M issues and other customized services which it offers to external customers.

Even more suppliers exist for cement plant optimisation, benchmarking and plant audits. Among the leading engineering consultants are Holtec Consulting, PEC Consulting, PEG Engineering, Penta Engineering, JAMCEM Consulting, CemCon AG, Cement Performance International (CPI) and Whitehopleman as well as the major equipment suppliers and equipment specialists such as FLSmidth, Thyssen Krupp Industrial Solutions, KHD Humbold Wedag, Siemens and ABB to name a few.

The concepts for plant optimization of the different suppliers seem to be very similar, although the tools may differ significantly. Such an optimisation always starts with a plant audit to get an independent assessment of the plant condition, identifying bottlenecks [10, 11]. In a second step opportunities for improvement are derived from benchmarking methods. In the final step a report is prepared in which measures are outlined as to how the gap can be closed and how the opportunities can be taken advantage of.

Other services that are offered include:

Energy optimisation

Product quality enhancement

Remote plant operations & efficiency monitoring

Capacity balancing & enhancement

Productivity improvements

6 Outlook

The cement services sector generates higher margins for suppliers than the equipment supply sector. This was true in the past and will probably continue to be true in the future. Suppliers like FLSmidth already generate higher revenues in the cement business from cement services than from equipment supply. At the moment, especially, the demand for outsourcing is fast growing due to the needs of larger cement plants for adequate performance management and reduced personal in the plants.

With O&M services from third parties, cement plant owners are able to reduce their fixed costs which today become more and more important in a cash-flow fixed industry. Accordingly it is forecast that the trends will continue in this decade and might even accelerate in the next decade. On the other hand more service providers will enter the market and the services will become more competitive while margins shrink.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.