Latest waste heat utilization trends in cement plants

Over the last two to three years there has been a distinct rise in the use of non-conventional waste heat recovery systems (WHR). One reason for this is the increasing competitiveness of these technologies due to the larger number of references and experience with the systems.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

An analysis of the available technologies for power generation from waste heat shows that there are three different processes, which all have their advantages and disadvantages:

Steam Rankine Cycle (conventional steam process)

Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC)

Kalina Cycle

2 Technical parameters of waste heat utilization

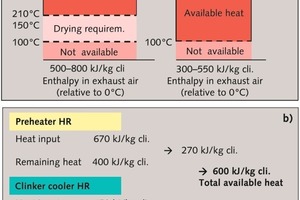

Since 2010, there has, however, been a second trend returning to lower conversion rates. This arises from the optimization of the clinker burning process in new cement kiln lines in China, which results in lower specific quantities of energy for the clinker production. Higher efficiency rates of the cement production plants lead to lower kiln and cooler exhaust air temperatures and thus reduce the amount of energy available for the waste heat utilization system (Fig. 2a). Fundamentally, the plant efficiency rates and the available waste heat potential depend on the number of preheater stages in the kiln system and on the raw material moisture content and amount of heat or temperature level required for drying the raw material. Table 1 shows the most important interrelations. Nowadays, most plants are equipped with 5-stage preheaters [2].

The second major waste heat potential is the exhaust air of the clinker cooler. Nowadays, grate coolers of the 3rd and 4th generations are installed at practically all production plants [3]. The specific cooling air volumes of such grate coolers are in the range of 1.7 to 1.9 Nm3/kg of clinker. The greater portion of this cooling air is returned to the clinker burning process (recuperated) as secondary and tertiary air. The cooler exhaust air only makes up 20-25 % of the quantity of heat used in the cooler. Accordingly, the enthalpies of the exhaust air from the cooler are only in the range of 300–470 kJ/kg of clinker. In order to obtain higher temperatures from the clinker cooler with enthalpies of up to 550 kJ/kg, so-called mid-air extraction points have been increasingly installed in the recent past. Mid-air extraction enables significantly hotter exhaust air to be obtained from the clinker cooler, e.g. 450 °C instead of 250 °C, without causing any significant change in the process parameters of the kiln system.

The heat quantities depend on the temperature level of the exhaust air and the exhaust air volume. The enthalpies of the preheater exhaust air and that of the clinker cooler exhaust air are normally in a ratio of 3:2. However, every individual plant has to be considered separately. Figure 2b shows an example calculation for the amounts of heat available in the kiln exhaust gas and the cooler exhaust air. The amount of utilized heat from the cooler is greater than that from the kiln exhaust gas because around 400 kJ of kiln exhaust gas per kg of clinker is used for raw material drying purposes. The kiln exhaust gas is therefore first routed to the waste heat boiler, and the remaining heat after the waste heat boiler is then used for drying purposes. A total of 600 kJ/kg of clinker is available as heat from the waste heat boiler. At an assumed power generation system efficiency of 25 %, it is thereby possible to generate 41.7 kWh per tonne of clinker.

3 Market development/market trends

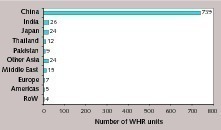

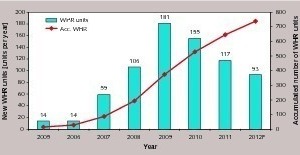

At the moment, China has 739 systems, which represents a share of 85.4 % of the global market. Figure 4 shows how the figures for China have developed since 2005. This overview only includes the systems that are actually in operation. After relatively low numbers in the initial years, 2009 was a boom year with 181 systems put into operation. Since then, the number of new systems has steadily decreased. This is due to three main factors.

The number of new cement production lines is currently decreasing due to the emerging surplus capacity on the market.

The potential for retrofitting WHR systems in existing clinker production lines is declining. The China Cement Association (CCA) presumes that less than 25 % of the existent modern kiln lines can be retrofitted with WHR systems.

Requests for funding within the framework of CDM programmes have decreased. Up to the end of 2010, a total of 217 WHR projects had been subsidized, which corresponds to 41 % of Chinese projects up to that point in time.

Up to now, Chinese cement plants have almost exclusively used conventional WHR systems with a water-steam circuit [4]. Only three plants have tried out other processes. There are currently seven well-known local system providers on the Chinese market, plus the further suppliers Conch Kawasaki (Chinese-Japanese joint venture) and JFE (Japanese system provider). All these suppliers had 819 reference systems in China at the end of 2012, which is 80 more than the number of systems that are in operation. The market leaders are Sinoma-EC, Conch-Kawasaki, NKK = Nanjing Kesen Kenen (member of CNBM Group and formerly called Nanjing Triumph), Dalian East and Citic Heavy Industries. Pure manufacturers of waste heat boilers like Jianglian (JJIEC) or pure suppliers of generators are not here considered to be system providers.

4 Technologies/general conditions

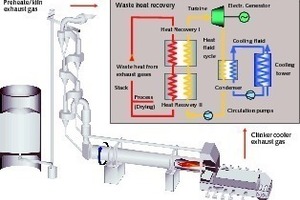

The design of the clinker production line does not have to be modified. Only the exhaust gas streams of the preheater and clinker cooler are either completely or partially utilized for the heat recovery. Correspondingly, the WHR system can be regarded as a separate system. The heat recovery takes place in separate waste heat boilers or recuperators for the kiln exhaust gas and the cooler exhaust air. Depending on the selected process fluid, an additional heat exchanger circuit may be interposed. The extracted thermal energy is used for driving a turbine, which transfers its mechanical energy to an electrical power generator. The process fluid is cooled down in a condenser by means of a downstream cooling circuit in order to achieve the greatest possible temperature gradient before and after the turbine. The process fluid is then pumped back into the circuit.

In the cement industry, the efficiency of the steam turbine process is around 20-25 %, i.e. only 1/5 to 1/4 of the waste heat can be transformed into electrical energy. In order to improve the efficiency, the waste heat boilers (Fig. 9) are executed as multi-pressure boilers with economizer, evaporator and superheater. As regards the type of construction, both vertically and horizontally arranged heat exchanger pipes have proved effective. Sinoma-EC has stated that by using vertical intake flow the construction size can be reduced by a factor of 2.5 [5]. In the 2nd and 3rd system generations of Chinese suppliers, the superheated steam from the kiln waste heat boiler is mixed with the hotter superheated steam from the cooler waste heat boiler. This boosts the temperature by a further 50-60 °C, so that it gains extra energy of up to 45 kWh/t of clinker.

Aside from the mentioned Chinese vendors and 3 further Chinese firms, the most important suppliers of conventional steam-process waste heat utilization systems are Conch Kawasaki, JFE Engineering Corporation, TESPL (Transparent Energy Systems), who hold a licence from Nanjing Triumph, BHEL, Thermax India and Krupp Polysius, who have a cooperation agreement with Dalian East. The steam circuit process is regarded as technically mature, and no significant differences can be found in the technology offered by the various vendors. Kawasaki’s system can still be regarded as the benchmark, and this supplier has the longest experience on the sector.

The Kalina process is a modified Rankine process, in which a binary water-ammonia mixture is used as the working medium. The advantage of the employed process fluid is that the vaporization and condensation temperatures can be adjusted, meaning that the process can even be used with the lowest exhaust heat temperatures of below 150 °C. As water and ammonia possess similar molecular weights, the system can be equipped with conventional steam turbines for the power generation (Fig. 11).

However, both the ORC and the Kalina process are more complex than water/steam circuits with regard to the technical equipment. Nevertheless, these processes are already employed in a large number of other heat-utilization sectors, for example geothermal power stations and combined heat and power generation plants. For system capacities of 1 to 10 MW, compact systems are available. These are also interesting for the cement industry.

There are only a handful of system suppliers for the cement industry. The most important suppliers of ORC systems for the cement industry are Turboden, a Pratt & Whitney company, and ABB. In addition to these, TMEIC is also active on the cement sector. For the Kalina process, FLSmidth has established itself on the market as a licensee of Wasabi Energy (Recurrent Engineering). Other licensees of Wasabi are Shanghai Shenge and Siemens, but these companies have not up to now delivered a single WHR system of their own manufacture to the cement industry. The ORC and Kalina processes are now regarded as technically mature. However, the technologies have not so far been implemented for system capacities above 10 MW. Up to now, the published efficiency rates achieved by WHR systems for power generation in cement plants are 21–22 %.

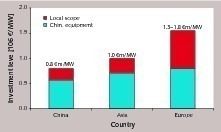

Due to the low capital cost of the Steam Rankine process, ORC and Kalina systems still have a competitive disadvantage. Vendors of such systems say that they are around 10 % more expensive than conventional steam processes. The question is: what price levels are being compared? Turboden states that the capital cost for ORC systems are € 2.5 million per MW in the most inexpensive case (10 MW capacity), ranging up to € 4.5 million in the most expensive case (1 MW capacity). However, the big monetary advantage of ORC systems is that their operating costs and maintenance expenses (O+M) are very low by comparison, at only € 0.035 million per MW and year. At this point it should again be pointed out that in CDM documents for conventional steam processes and medium system sizes the O+M costs are put at 10 % of the capital cost, which obstructs short payback periods.

The capital costs of the systems are not insignificantly dependent on which cooling system is selected and how far it is able to reduce the temperature at the cold end. Normally, wet cooling towers or dry/wet hybrid cooling systems are employed. With wet cooling towers the temperature of the process fluid can be reduced to below 25 °C. The used water is extensively recirculated, although a high amount evaporates. In certain regions it is expedient to use the residual heat for heating purposes or for greenhouses that can be built at the periphery of cement plants.

5 Case examples

The following heat balance has been calculated for the 7000 t/d plant with 5-stage preheater: The heat input from fuel and air is 3291 kJ/kgcli. The kiln system needs a process heat level of 1717 kJ/kg i.e. 52.2 %. The waste heat from the kiln exhaust gases makes up 682 kJ/kg (20.7 %), while the waste heat from the cooler exhaust air accounts for 486 kJ/kg (12.35). Approx. 8 % of the energy from the residual heat of the kiln exhaust gas is required for drying the raw material. The WHR system can generate 164.5 GWh of energy per year, which corresponds to 34 % of the 481.8 GWh of electrical power required for the three kiln lines with their total clinker output of 15 000 t/d. As a result, approx. 37 200 t of heavy oil will be saved every year, which represents an annual CO2 emission reduction of around 145 000 t, due to the WHR system. The estimated cost of the power generation is 0.0271 SR/kWh. By comparison, the cost of power generation with the diesel generators is 0.997 SR/KWh.

6 Prospects

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.