Solidification of simulated borate liquid wastes with alkali-activated slag cements

The solidification of borate solutions with alkali-activated slag cements (AASC) was studied. The results showed that AASC activated with 7.5% NaOH had acceptable setting times, and that the compressive strength of the solidified waste after curing for 28 d varied between 26 and 30 MPa, depending on both the concentration (60 – 240 g/l) and the pH value (8.5 – 10.5) of the associated borate solution. Increasing the concentration of the borate solution and lowering the pH resulted in a reduced rate of setting of the fresh AASC paste, retardation in the structural formation of the hardened AASC paste, a reduced degree of hydration, and suppression of the formation of C-(A)-S-H. Parameters such as setting times, development of compressive strength, and waste loading can be influenced by the NaOH/H3BO3 ratio, which must be ≥ 1.

1 Introduction

Operational and decommissioning activities in different nuclear facilities generate large volumes of various types of radioactive waste (RW) streams [26], which are categorized as gaseous, liquid, dry solids or wet solids, depending on their physical state [1, 45]. Boric acid (H3BO3) is one of the most common types of liquid waste concentrate generated by pressurized water reactors. Boric acid waste is first neutralized using sodium hydroxide, then concentrated via evaporation. The resulting borate slurry is usually immobilized in cement, polymers, or bitumen [14, 20, 24]....

1 Introduction

Operational and decommissioning activities in different nuclear facilities generate large volumes of various types of radioactive waste (RW) streams [26], which are categorized as gaseous, liquid, dry solids or wet solids, depending on their physical state [1, 45]. Boric acid (H3BO3) is one of the most common types of liquid waste concentrate generated by pressurized water reactors. Boric acid waste is first neutralized using sodium hydroxide, then concentrated via evaporation. The resulting borate slurry is usually immobilized in cement, polymers, or bitumen [14, 20, 24]. Portland cement (PC) and its variants are the most widely used mineral matrices for the cementation of low- and intermediate-level radioactive wastes (activity level >0.01 mSv (annual dose to members of the public) and thermal power <2 kW/m3 [27]). However, PC does not always ensure the efficiency of immobilization and accommodation of high load with wastes of diverse composition, including borate liquid RW. The main problem in the solidification of boric acid and borate using PC is its strong retarding effect on the setting times of the waste forms [3, 11, 29, 43]. Borate or poly-boric anions react with the calcium-containing species in PC, resulting in surface adsorption and the formation of compounds such as calcium borate. The presence of these low-solubility layers precipitated over the cement particles inhibits flocculation and leads to retardation of the setting time of the mixture [4, 6, 10, 44]. According to [44], calcium borate (2CaO·3B2O3·8H2O) can precipitate within a pH range of 4.5 – 12 and cause this inhibition effect. The inhibition effect from the borates often lowers the waste loading needed to obtain qualified solidified waste.

Several approaches have been developed to improve the cementation of borate RW. One is the incorporation of different additives into the Portland cement-based matrix formulation, and the other is the use of blended cements [22, 32, 34, 41]. The problem of low pH arising from the presence of boric acid can be solved by incorporating hydrated lime in both Portland cement-based and non-clinker matrices [33, 41]. There are also physical and chemical methods that can speed up the setting and hardening processes in cement compounds that contain liquid RW including aqueous solutions of boron at low pH. [18] reported that electromagnetic treatment of liquid radioactive waste changes the ionic form of the borates and increases the pH due to dissociation of the oxygen and hydrogen bonds in the aqueous solutions of the boron compounds.

Another way to improve the technological and final properties of the solidified borate liquid RW using inorganic binders is to look for alternative binders. Alternative binders designed to have a lower carbon footprint or produced during the processing of cement industry waste are being developed worldwide and will be extensively available in the future, at which time the waste produced today will need to be stabilized. The cement paradigm is currently moving from a single universal cement based on OPC to an array of cement types, such as calcium aluminate or sulphoaluminate cements, alkali-activated materials, Mg-based binders, and supersulphated cements, among others [15]. Many studies have already reported the efficacy of alternative binders for immobilising toxic and radioactive wastes. Alternative cements produce a diverse range of reaction products which, when compared to OPC, are characterised by lower solubility and ion exchange properties, different pH, faster hardening, lower permeability of hardened pastes, etc. Alternative binders ‘push the envelope’ of cementation technology for toxic and radioactive wastes by:

in some cases, exhibiting higher efficiencies for both physical separation and chemical binding of heavy metals and radionuclides

broadening the range of wastes that can be immobilised by cementation

optimising the waste cementation technology in cases where the cement contains components that are difficult to treat via faster curing of cementitious waste forms, thus eliminating the need for waste pre-treatment, etc.; and

facilitating the use of alternative binders as adsorbents and chemical additives [2]

With respect to borate RW, quick-hardening alternative binders such as calcium aluminate, sulpho-aluminate, and magnesium phosphate cements can have higher efficiencies than PC [8, 17, 23, 25, 40, 50].

Many studies [35, 37, 48] have reported on the effectiveness of alkali-activated cements for different kinds of RW. Matrices based on alkali-activated cements are already being successfully used in practical applications [46, 31]. Alkali-activated cements also exhibit satisfactory performance as matrices for the solidification of ‘problematic’ RW in PC. Our earlier study [42] reported that alkali-activated slag (AASC) and alkali-activated slag-metakaolin cements were more effective than PC in the solidification of nitrate solutions with concentrations in the range of 100–700 g/l. With respect to boron-based RW, [35] found that a high concentration of boron-containing salts did not affect the properties of alkali-activated fly ash cements. Experimental results indicated that the leaching indices and diffusion coefficients of boron in the activated fly ash-based matrix were 100 times lower than those in the Portland cement-based matrix. The authors concluded that the boron present in the system would precipitate as NaB(OH)4 or other sodium borates, which would fill the voids in the matrix. The main factor affecting the degree of leaching was the solubility of these compounds in the usually rather highly alkaline matrix. The presence of boron does not significantly modify the mechanical strength of activated fly ash; also, boron leaching tests have indicated that this stabilization/solidification is more effective than traditional routes.

This work focuses on the solidification of simulated radioactive liquid borate wastes with AASC. The properties of the fresh and hardened pastes, the hydration products, and the microstructure of the hardened matrices were studied as a function of different parameters such as the dose of the alkali activator, the concentration, and the pH of the borate solutions. The dependence of these properties on the factors listed in Figure 1 is examined in detail.

2 Experimental details

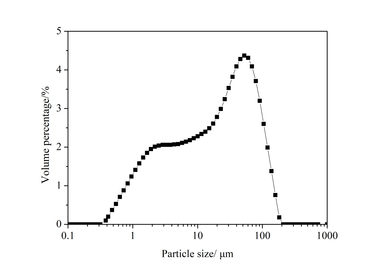

Granulated blast furnace slag (GBFS) obtained from the Magnitogorsky factory was ground in a laboratory planetary mill to a specific surface area (Ssp) of 280 m2/kg (Blaine). The chemical composition of GGBFS is shown in Table 1.

The alkaline activation of the AASC cements was carried out using commercial NaOH. The NaOH concentrations used were 2.5 g, 5 g, and 7.5 g per 100 g of GGBFS.

Borate solutions designed to simulate real borate radioactive liquid waste produced in a nuclear power plant’s pressurized water reactor were prepared by dissolving H3BO3 and NaOH in tap water. A control sample was prepared using an equal volume of tap water. The concentrations of NaOH, H3BO3, and the simulated borate solutions used in the experiments are listed in Table 2. A device Controller pH-2x-003 was used to measure the pH level in borate solutions. Cementitious waste samples were prepared by mixing water or borate solutions with a dry mix of GGBFS and NaOH. Initially, GGBFS and NaOH were mixed in a dry state for one minute, after which the water or borate solution was gradually added while stirring with a hand mixer for about 3 minutes. A liquid/solid ratio of 0.5 provided a workable and appropriate flowability. Fluidity was determined on an ‘AzNII Kr-1 Cone’ device consisting of a cone-shaped vessel mounted on a measuring table printed with concentric circles having diameters ranging between 70 and 250 mm. The flowability of cement compounds was 180 mm (GOST 26798.1-96, 1996). A Vicat’s apparatus was used to measure the setting times in accordance with the method outlined in the EN 196-3 standard (EN 196-3, 1987). The AASC paste samples were prepared in cubic moulds (2 x 2 x 2 cm) for compressive strength tests (test apparatus: PGM-50MG4 with a load rate of 0.12+0.2 MPa/s), and then demoulded for 1 day. The cubes were stored for 28 days in sealed plastic bags in a chamber at room temperature and 98 % relative humidity; they were also subjected to 90 days of immersion in water before testing. Compression tests were performed by applying a load between the two surfaces that were vertical during casting. The cube dimensions were measured with Vernier callipers in order to perform the strength calculation. Each strength determination quoted is based on the average of six measurements from the same cast.

Calorimetry experiments were carried out using “Thermochron” metering equipment at 28° C. The pastes were mixed externally and placed in sealed glass ampoules, which were then loaded into the calorimeter. The time elapsed between the addition of the activating solution to the powder and the loading of the paste into the calorimeter was approximately 3 – 4 min. The tests were run for 48 h.

Spectrum analysis (Spectrometer ELAN 9000) was used to measure the chemical composition of the GGBFS. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were performed on crushed paste samples that had been aged for 28 days. Hydration was stopped via solvent exchange with isopropanol. An STA 409 РС Luxx simultaneous thermal analysis apparatus was used for TGA. The samples were heated from 30° C to 1000° C at a heating rate of 10 K/min. XRD data were collected using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer in a θ–2θ configuration, with Cu Kα radiation, operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. The specimens were collected in the 2θ range 3–65° with a scanning rate of 17°/s and a step size of 0.017° 2θ. Data handling was performed using the Diffracplus Evaluation Package e EVA Search/Match and database PDF-2 ICDD. Fragments of selected samples that had been cured for 28 days were coated with an Au/Pd alloy for electron microscopy using a Merlin microscope from Carl Zeiss, accelerating voltage 20 keV, working distance 9 mm.

3 Results

3.1 Properties of fresh and hardened AASC pastes

Table 3 shows the setting times of the fresh AASC pastes made with different concentrations of NaOH, along with the pH of the simulated borate solutions.

It is well known that the cemented wastes should be allowed to set for more than 5 h to avoid any setting within the mixer in the event of a technical problem, and for less than 24 h to enable good output from the conditioning unit [7]. The results of the current study demonstrate that mixing AASC with a borate solution slowed the setting process, and that the setting times increased with i) decreasing activator (NaOH) dose and ii) decreasing pH of the borate solutions. AASC activated with 2.5 % NaOH could be used only for the solidification of low-density borate solutions – 60 g/l at pH 8.5 and 60 – 120 g/l at pH 10.5 – within acceptable setting times. Increasing the activator concentration to 5 % provided acceptable setting times for borate solutions with concentrations of 60 – 120 g/l at pH 8.5 and throughout the selected range of concentrations from 60 – 240 g/l at pH 10.5.

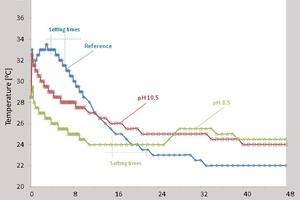

When the activator content was increased further to 7.5%, acceptable setting times were observed when borate solutions of both low and high concentrations were solidified at pH 8.5 and 10.5. This data is in agreement with the results shown in Figure 2, which illustrates the influence of the pH of the borate solutions at a concentration of 240 g/l on the temperature in fresh AASC pastes activated by 5 and 7.5 % NaOH.

As can be seen from the data, the increase in activator dosage from 5 to 7.5 % leads to increases in the reaction temperature and peak intensities. The initial peak corresponds to the setting times for the reference formulations. According to [47], in NaOH-activated slag cements, the initial peak is attributed to the wetting and dissolution of slag particles and to the precipitation of a very thin layer with a low Ca/Si ratio. The thin layer, presumably consisting of C–(A)–S–H, has low solubility. The temperature curve for the AASC mixed with borate solution 4 (pH 8.5) and characterised by a final set after more than 24 h has no peaks. Unlike the reference sample, the other samples had peaks corresponding to the beginning of the structure formation process, which did not coincide with the setting times. In these cases, the peaks were broader and occurred at lower temperatures than in the reference sample. The reason for this mismatch is probably that the setting times were determined not by the formation of the reaction products but by the precipitation of borate salts. Actually, ‘bulk’ reaction products began to form later, as reflected by the broad peaks in the temperature curves. Figure 3 shows the 28-day compressive strengths of hardened AASC pastes prepared with different concentrations of NaOН and borate solutions, and at different pH values. These data show that AASC activated with 2.5 % NaOH does not solidify borate solutions 1 – 4 (pH 8.5), but does solidify borate solutions 5 – 8 (pH 10.5). The results also show that the compressive strength of the product is comparable to that of the reference sample. Increasing the dosage of the alkaline component to 5 or 7.5% improves the ‘solidifying properties’ of the matrices, and the strengths of AASC mixed with borate solutions 1 – 8 are not impaired. An increase in the concentration of the borate solution increases the 28-day compressive strength of the hardened AASC pastes from 18 to 21 – 23 MPa and from 25 to 28 – 30 MPa at NaOH dosages of 5 and 7.5 %, respectively. It should also be noted that the cemented waste forms demonstrate water resistance and do not lose compressive strength after 3-month immersion tests.

3.2 Influence of borate solutions on the composition of the hydration products and the microstructure of hardened AASC pastes

The matrix formulations, for which the compositions of the hydration products and the microstructures of the hardened AASC pastes were studied, are listed in Table 4.

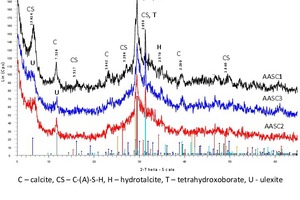

It is well known that alkali activation of GGBFS results predominantly in the formation of C-(A)-S-H gel [39, 16, 30]. This phase is detected as a broad ‘hump’ by XRD analysis (Figure 4). The XRD patterns of the AASC1–AASC4 hardened pastes shown in Figure 4 also indicate “relict” GGBFS minerals – gehlenite, akermanite, hatrurite, srebrodolskite. The main reaction products in the 28-day cured system of GGBFS– NSH5–borate solution are C-(A)-S-H, calcite (CaCO3) (reflection at 29.395 2θ, PDF 01-071-3699), hydrotalcite (MgO6.667Al0.333)(OH)2(CO3)0.167(H2O)0.5 (reflection at 11.649 2θ, PDF 01-089-0460), calcium silicate hydrate C-S-H (I) CaO.SiO2.H2O (reflection at 7.066 2θ, PDF 00-0034-0002), calcium silicate hydrate C-S-H Ca1.5.SiO3.5.H2O (reflection at 29.356 2θ, PDF 00-033-0306), ulexite NaCaB5O6(OH)6(H2O)5 (reflection at 7.14 2θ, PDF 01-083-1664) and calcium aluminium borate hydroxide hydrate Ca6Al2(B(OH)4)3.8(OH)14.2.20H2O (reflections at 16.073 and 26.049 2θ, PDF 00-047-0419). To accelerate the reaction between mineral matrix and borate salt, the XRD analysis was additionally performed for samples prepared of GGBFS of 800 m2/kg (AASC4). As a result, the peaks of ulexite are now evident and more “clear”. The XRD-pattern of this sample is presented in Figure 4b.

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies [5, 9, 28, 38, 49] that reported the results of XRD analyses of AASC pastes and sodium borate salts.

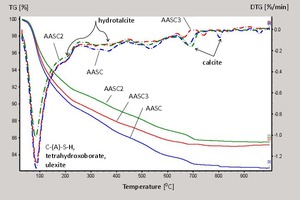

Data from the thermogravimetric analyses (TGA and DTG) are shown in Figure 5 and Table 5.

It is evident that the reaction products partially observed via XRD are also identified in the thermogravimetric analyses. Based on the data from the 28-day-cured AASC1 – AASC3 pastes, the maximum weight loss occurs in the range of 30 – 260 °C, which is associated with C–(A)-S–H and hydrated borate minerals. Because the hardened AASC1 paste has the highest weight loss of 10.74 %, as compared to both AASC3 (10.08 %) and AASC2 (8.70 %), it can be concluded that the reference sample of hardened AASC1 paste contains more C–(A)-S–H and bound water than AASC2 and AASC3. The total weight loss up to 600° C is considered to be a relative measure of the degree of hydration in binder systems [13, 21]. Based on the values of total weight loss for the different compositions of the hardened pastes, their degrees of hydration can be described in increasing order as AASC1 > AASC3 > AASC2. This indicates that the decrease in the pH of the simulated borate solution suppresses the formation of C–(A)-S–H.

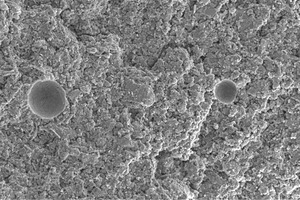

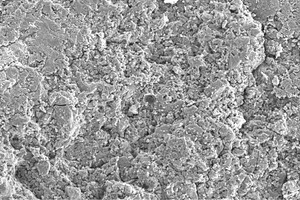

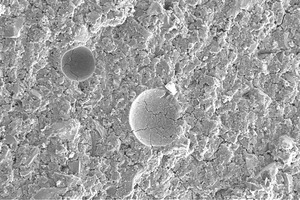

A comparison of Figures 6 to 8, which are SEM analysis images of 28-day-cured AASC1–AASC3 pastes, does not reveal any visible differences in the microstructures of the samples investigated.

4 Discussion

A comprehensive analysis of the results presented in Section 3 suggests the following sequence of interactions from the mixing of the starting materials to the formation of the hardened pastes in the GGBFS–NaOH–borate solution system.

Immediately after mixing the constituents of AASC with simulated liquid borate waste, the liquid phase of the fresh paste generally consisted of Na+ cations (from NaOH and the borate solution), OH- anions (from NaOH), Ca2+ cations (from GGBFS destruction), H+ cations and B(OH)4- anions (from the borate solution). In the AASC–borate solution system under consideration, anions can react with:

H+, to form H2O

Na+, to form NaB(OH)4 or other kinds of sodium borates, as reported for fly ash–NaOH–boric acid systems [30]

Ca2+, leading to the formation of 2CaO · 3B2O3 · 8H2O [14] or CaO·B2O3 · 6H2O [15], as reported for Portland cement–borate systems; and

Na+ and Ca2+, leading to the formation of borate minerals containing sodium and calcium ulexite [NaCaB5O6(OH)6.5H2O], as reported for calcium sulfoaluminate cement [23]

Presumably, the following processes occur:

Interaction of H+ and OH- to form H2O

interaction of B(OH)4- and Na+ to form NaB(OH)4 or other kinds of sodium borates; NaB(OH)4 in turn can form crystalline hydrates of soluble tetrahydroxoborate NaB(OH)4∙2H2O

Initiation of the destruction of GGBFS by OH- groups, resulting in the rupture of the Si–O–Si bonds and the release of Ca2+

Transformation of soluble NaB(OH)4 as Ca2+ is released from GGBFS into slightly soluble NaCaB5O6(OH)6∙5H2O; and

Interaction of B(OH)4- and Сa+ with the formation of calcium aluminium borate hydroxide hydrate Ca6Al2(B(OH)4)3.8(OH)14.2.20H2O

The data in Table 3 and Figure 2 show that an increase in the borate solution concentration, a decrease in the pH, or a lower dosage of the alkaline activator NaOH retards the setting of the fresh paste. Under these conditions, the temperature of the reaction decreases, and the initial peaks are seen after the final setting of the material. These observations allow us to conclude that the destruction of slag and the structure formation process begin or accelerate after completion of the reaction between H+ cations from the borate solution and OH- groups from the alkaline activator to form H2O, as well as the reaction of the borate anions with Na+ to form NaB(OH)4. Correspondingly, the higher the concentration of hydrogen cations (which prevent the destruction of GGBFS by reacting with OH- groups), the greater the slowing effect. It also appears that more Na+ groups are available for reactions with B(OH)4- than Ca2+, because the amount of sodium borate is greater than the amount of calcium borate, although this statement requires verification via further studies.

The next important conclusion from the experimental data is that the setting times and the ‘solidifying properties’ of AASC strongly depend on the ratio of H3BO3 to NaOH. According to experimental data on the hardened pastes prepared with an NaOH dosage of 2.5 % and borate solution concentrations of 120 – 240 g/l at pH 8.5, the H3BO3/NaOH ratio was greater than 2.5. The fresh paste did not set and harden, because the alkali activator was completely consumed by the borate. NaOH dosages of 5 and 7.5 % are sufficient for the binding of borates, followed by the activation of GGBFS, resulting in gradual strengthening of the AASC paste. Finally, with a high dosage of NaOH (7.5 %), the setting times and compressive strength characteristics were acceptable across the entire range of concentrations studied both at pH 8.5 and 10.5. In order to reduce borate-influenced slowing of cement hardening, a process based on hydration reactions with water similar to those associated with Portland cement and calcium sulphoaluminate cements, an additional Ca2+ source in the form of hydrated lime [Ca(OH)2] is normally used. Thus, contrary to what is seen in the GGBFS–NaOH–borate solution system, the alkali activator played roles in both binding the borates and ensuring the hardening of the matrix through activation of GGBFS. The interaction between the alkali activator and the borate solution was also confirmed by the fact that, for an equal dosage of NaOH, i.e., 7.5 %, as per the results of thermogravimetric analysis, the hardened pastes prepared with borates as the mixing solution exhibited a lesser degree of hydration and a lesser volume of C–(A)-S–H than those prepared with water.

Our results on the influence of the borate solutions on the compressive strengths of the hardened waste forms are in agreement with those of [30], in that boron does not significantly modify the mechanical strengths of the hardened pastes. According to [30], NaB(OH)4 or other kinds of sodium borates partially fill the voids, pores, etc. throughout the whole matrix. Our results showed that the strengths of hardened slag pastes activated by 5 – 7.5 % NaOH mixed with borate solutions exceed those mixed with water. Additional research is needed to confirm this finding.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, the feasibility of solidifying borate solutions with concentrations of 60 – 240 g/l at pH values of 8.5 and 10.5 with alkali-activated slag was analysed, and the properties of the fresh and hardened pastes, the hydration products, and the microstructure of the solidified waste forms were studied. The following conclusions were reached:

1. The AASC-based mineral matrix was suitable and efficient for the solidification of borate solutions with concentrations of 60 – 240 g/L at pH values of 8.5 and 10.5. AASC activated by 7.5 % NaOH led to acceptable setting times, and the compressive strength of solidified waste forms that had been cured for 28 days was in the range of 26 – 30 MPa, depending on the pH of the borate solutions. The compressive strength did not decrease after 3-month immersion tests.

2. The ability of AASC to solidify the borate solutions depended on the dosage of the alkali activator NaOH and the concentrations and pH of the borate solutions. The increased concentrations and decreased pH of the borate solutions led to slower setting of the fresh AASC paste and to the destruction of the GGBFS structure formation process. The setting times, the development of compressive strength, and increased waste loading can be influenced by the NaOH/H3BO3 ratio, which must be approximately ≥ 1.

3. NaOH plays roles both in binding the borates and in improving the hardening of the matrix through the activation of GGBFS. Complex studies of fresh and hardened AASC pastes prepared with water and borate solutions have shown that the mechanism by which an AASC-based mineral matrix solidifies borate solutions is based on the precipitation of sodium, mixtures of sodium and calcium, and probably calcium borates following the activation of GGBFS with an alkali. The end result is the hardening of the cement waste forms.

4. An X-ray amorphous phase is the main hydration product of the solidified matrices. The crystalline phases for all of the samples studied suggested the presence of small amounts of aluminium-substituted calcium silicate hydrate, calcite, hydrotalcite, tetrahydroxoborate, ulexite and calcium aluminium borate hydroxide hydrate. The hardened AASC pastes made from formulations mixed with borate solutions were characterized by a lower degree of hydration and fewer aluminium-substituted calcium silicate hydrates.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.