Simulation of limestone calcination in normal shaft kilns –

Part 2: Influence of process parameters

For normal shaft kilns it is described how the axial profiles of the surface and core temperature of the stones, their decomposition and the gas temperature depend on the process parameters, which are stone size, energy input, throughput and type of fuel. In addition, the influence of these variables on the specific energy consumption, the residual CO2 content and the pressure drop is discussed.

1 Introduction

The calcination of limestone in normal shaft kilns is a complex process, since it is influenced by a variety of parameters. These influencing factors are:

the operating variables such as energy input, throughput, type of fuel, air flow,

the kiln parameters such as diameter, packed bed height, cooling zone length,

the limestone parameters such as mean particle size and material properties (thermal conductivity, coefficient of decomposition, decomposition pressure, calcite fraction, magnesite fraction, humidity, etc.)

ambient conditions (ambient temperature, air velocity, clouds).

The...

1 Introduction

The calcination of limestone in normal shaft kilns is a complex process, since it is influenced by a variety of parameters. These influencing factors are:

the operating variables such as energy input, throughput, type of fuel, air flow,

the kiln parameters such as diameter, packed bed height, cooling zone length,

the limestone parameters such as mean particle size and material properties (thermal conductivity, coefficient of decomposition, decomposition pressure, calcite fraction, magnesite fraction, humidity, etc.)

ambient conditions (ambient temperature, air velocity, clouds).

The first part of this paper described the development and structure of a simulation program with which the effect of these parameters on the combustion process can be calculated [1]. The basic profile of stone and gas temperatures and the decomposition degree were discussed. In addition, it has been shown how the specific energy demand, the residual CO2 content and the pressure drop can be calculated based on these profiles. In the present second part, it will be discussed how the process parameters stone size, energy input, product throughput and type of fuel affect the calcination process. In a subsequent third part, it will be described, how the limestone parameters (material properties, stone sizes, stone size distribution, etc.) affect the process.

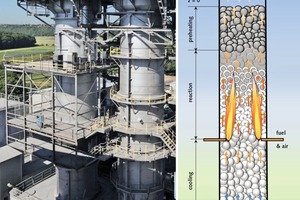

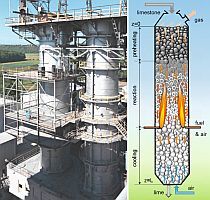

2 Process data

For the analysis of the calcination process of limestone in normal shaft kilns, a reference kiln having an inside diameter of 2.5 m, a total packed bed height of 14 m and a cooling zone length of 6 m was used, with natural gas H serving as fuel. Over the cross section of the kiln, a uniform distribution of fuel and air was assumed. This radical assumption must be made, as the exact distribution of the quantities of gas is still the current state of research and therefore as yet unknown. The kiln is filled with 344 tons of limestone a day. The output mass flow depends on the degree of decomposition (residual CO2). The CO2 content of the limestone is 42 %, while the magnesite and humidity effects are excluded here for better illustration. The cooling zone is operated with a lime-air capacity flow ratio of one. This results in the minimum amount of air for cooling. Therefore the largest possible quantity of air can be injected with the fuel, which results in an improved cross-distribution. The combined amount of cooling air and injected air (with fuel) leads to an overall excess air number of 1.3. The bed is monodisperse. As mentioned, the influence of the size distribution of the stones will be analyzed in a subsequent article.

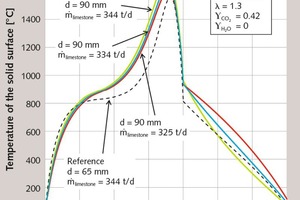

3 Influence of stone size

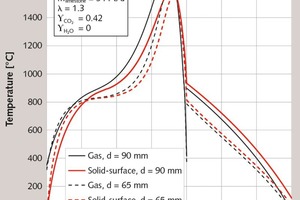

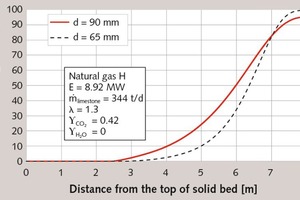

First, the influence of the stone size will be discussed. In Figure 1, the axial profiles of the surface temperature of the stones and of the gas temperature of a monodisperse bed with 90 mm and 65 mm particle diameters are shown. In Figure 2, the corresponding profile of conversion is depicted, this is the local weight loss related to the maximum possible weight loss. The stones are fed into the kiln with ambient temperature. The small stones with 65 mm heat up more quickly to the equilibrium temperature of about 820 °C, since the heat transfer is higher the smaller the particle diameter. Thereafter, however, the temperature of the large stones rises more quickly, since the gas temperature is higher. Accordingly, the decomposition begins a little earlier. The decomposition stops when the gas temperature falls below the surface temperature of the stones.

The fuel is injected with ambient air at 8 m and mixes perfectly with the cooling air to a temperature of about 400 °C. This combustion gas is then heated by the stones. This cools them down to a temperature of about 800 °C to 900 °C, before they are cooled further in the cooling zone. The decomposition of the large stones is slightly less pronounced than that of the smaller stones. Thereby, the amount of supplied fuel energy being bound as decomposition energy is smaller. The difference is in the flue gas, so that its temperature is higher for the large stones than for the small stones. For the large stones, the temperature profile in the decomposition zone is shifted by about one meter to the kiln head.

The characteristic simulation results are summarized in Table 1. The 65 mm particles are almost completely decomposed with a residual CO2 content of 0.3 %, which corresponds to a degree of conversion of 99.6 %. At 3.4 %, the 90 mm particles have a significantly higher residual CO2 content. The energy consumption of the discharged product is slightly lower for the 90 mm stones, because due to the higher residual CO2 content more mass is discharged. Referring the energy consumption to the CaO content shows that the smaller stones have the lower value, because this proportion is correspondingly higher. As explained above, the flue gas temperature for the large stones is higher. The discharge temperature of the stones is also higher. The maximum gas and stone surface temperatures are about the same. For small stones, the pressure drop is higher, because it reciprocally depends on the stone size.

Based on the results obtained, it will be discussed subsequently how the process can be regulated when the limestone size is changed from 65 mm to 90 mm to ensure consistent product quality. For the stone size of 90 mm, an identical residual CO2 content of 0.3 % should be achieved.

4 Influence of energy input

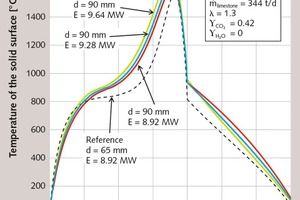

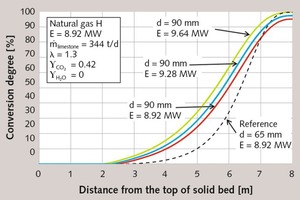

As first parameter, the energy supply is increased to lower the residual CO2 content of the 90 mm-diameter stones. In Figure 3, the axial profiles of the surface temperature of the stones are shown for an increased fuel supply of 4 % and 8 %. Figure 4 shows the associated decomposition profiles. In both figures, the profiles of the 65 mm stones are included as dotted lines. With increasing fuel supply, the gas temperature rises (not shown here) and with it the stone temperature. The decomposition therefore begins earlier and will reach a higher degree of decomposition.

In Table 1, the characteristic simulation results are in turn given as numerical values. With an 8 % higher fuel supply, a residual CO2 content of 0.3 % is reached, which the 65 mm stones also had. The specific energy consumption, the flue gas temperature, the maximum gas temperature and the maximum stone temperature rise with the fuel supply. Both maximum temperatures rise by almost 90 K. The pressure drop increases, because more gas flows through the kiln. In contrast, the lime discharge temperature decreases slightly, because the lime is cooled more strongly by the increased air input.

5 Influence of throughput

In the following, it is considered how the residual CO2 content of 90 mm stones can be reduced by reducing the throughput, with a constant energy supply. In Figure 5, the profiles of the surface temperatures are shown. The characteristic data are summarized in columns 5 and 6 of Table 1. A residual CO2 content of 0.3 % is therefore achieved with a reduction of the throughput by 5.5 %. However, this increases the specific energy consumption by about the same amount.

Therefore, the effect of lowering the throughput for an approximately constant specific energy consumption was observed (see columns 7 and 8 in Table 1). It can be seen that, in this case, the throughput must be lowered by about 20 % to reach a residual CO2 content of 2.4 %. By only reducing the throughput at constant specific energy consumption, no substantial reduction in residual CO2 content is achievable.

6 Influence of packed-bed height

The influence of the height of the packed bed is illustrated in columns 9 and 10 of Table 1, in which the characteristic data are again summarized. Considered are the two cases that the bed is increased from 14 m to 15 and 16 m, respectively. The 90 mm stones have more time available for decomposition. Consequently, the residual CO2 content decreases with the increase. For an increase of 2 m, a residual CO2 content of 2.2 % is achieved. The specific energy consumption and the temperatures vary only slightly, but the pressure drop increases considerably. Accordingly, it is not possible to decrease the residual CO2 content to 0.3 % for the 90 mm stones, even by increasing the height of the packed bed.

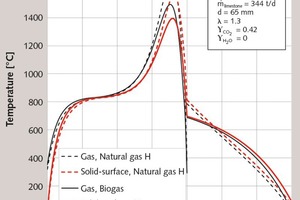

7 Influence of the type of fuel gas

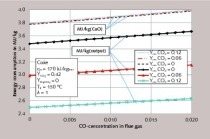

Finally, the influence of the type of fuel gas for the same stone size of 65 mm is discussed in Figure 6 and Table 2. Natural gas quality H is compared with a biogas consisting of 50 % each methane and carbon dioxide. For one and the same energy supply, the residual CO2 content rises to 4.3 %. To reach the residual CO2 content of 0.3 %, the energy consumption must be increased by about 8.7 %. The influence of the type of fuel on the energy consumption has already been explained by Bes et al. [2]. The onset of decomposition depends on the equilibrium temperature of the limestone, which acts as a so-called pinch point. The higher the CO2 content of the flue gas, the higher the equilibrium temperature and, hence, the flue gas temperature. Since biogas results in a much higher CO2 content in the flue gas than natural gas, the equilibrium temperature and thus the energy consumption are higher. The equilibrium temperature of the limestone also depends on its origin [3, 4].

Part 3 of this article in the next issue of ZKG will discuss how the origin of the limestone and therefore its material properties and the distribution of stone size influence the decomposition process.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.