Shrinkage of eco-friendly concretes made with limestone-rich cements

Excessive shrinkage deformation in concrete structures may lead to crack formation. Furthermore, in prestressed concrete elements shrinkage results in a significant loss of prestressing forces. Limestone-rich cements with limestone contents beyond the values of DIN EN 197-1 were developed in order to reduce the environmental impact of concrete. In this paper, the results of shrinkage behaviour of cement pastes and concretes made of limestone-rich cements up to 70 wt.-% are presented. Results revealed that the drying shrinkage of cement paste and concrete with high limestone contents strongly depends on the amount and the chemical-mineralogical properties of the limestone. In this context, methylene blue value (MB-value) and alkali oxide content of limestone were identified as the key parameters. Depending on the type of limestone, concrete samples made of limestone-rich cements had either higher or lower drying shrinkage than reference samples made of CEM I 52.5 R with the same w/c-ratio. However, lower drying shrinkage deformation was observed in comparison to the reference concrete made of CEM I with a comparable compressive strength.

1 Introduction

1.1 Problem definition and motivation

Concrete as the mass building material of the time is responsible for more than five percent of the global anthropogenic CO2 release [1]. The major environmental impact of concrete comes from the CO2 emissions during clinker production. It was realised that the reduction of Portland cement clinker in cement can lead to a decrease in the environmental impact of concrete. However, excessive substitution of clinker by limestone in Portland limestone cements (more than 35 wt.-%) with a common water/cement-ratio is reported to be critical [2]. To...

1 Introduction

1.1 Problem definition and motivation

Concrete as the mass building material of the time is responsible for more than five percent of the global anthropogenic CO2 release [1]. The major environmental impact of concrete comes from the CO2 emissions during clinker production. It was realised that the reduction of Portland cement clinker in cement can lead to a decrease in the environmental impact of concrete. However, excessive substitution of clinker by limestone in Portland limestone cements (more than 35 wt.-%) with a common water/cement-ratio is reported to be critical [2]. To overcome this problem, limestone-rich cements with high limestone contents up to 65 wt. -% were developed beyond the limits of EN 197-1 [3] based on a modified concrete technology proposed by [4]. This approach suggests a reduction of water content supported by the optimisation of the packing density and the use of high performance polycarboxylate ether superplasticizer. Concretes made with such cements with high limestone contents could show a significant reduction of CO2 emissions up to 35 % compared to the reference concrete from German average cement with comparable mechanical and durability properties [3]. Preliminary studies showed that the long-term deformation of concretes made of limestone-rich cements depends strongly on the chemical mineralogical properties of the ground limestone used as the main cement component [3]. Significant change in the drying shrinkage and creep deformations up to 80% was reported when the type of limestone was varied. Nevertheless, studies to investigate the influence of chemical-mineralogical properties and high-contents of limestone as main cement component on the shrinkage deformation of hardened cement paste (hcp) and concrete are lacking so far.

1.2 Shrinkage of cementitious materials and influencing factors

Cracking due to shrinkage can shorten the service life of the structure by cracking and easing the penetration of aggressive mediums. Meanwhile, shrinkage deformation results in a significant loss of prestressing forces which affects the bearing capacity of prestressed concrete. Based on the origin and start time, shrinkage can be categorised into plastic shrinkage, chemical shrinkage, carbonation shrinkage, autogenous shrinkage and drying shrinkage [5, 6].

Three mechanisms are proposed as the main driving forces for the drying shrinkage of concrete [7–10]. These include:

1) surface free energy

2) capillary tension

3) disjoining pressure

The capillary tension acts when the capillary and gel pores are almost filled with water or condensed water from vapour (denoting RH > 80 %). Autogenous shrinkage is defined as the isothermal macroscopic load-independent volume change of cement paste or concrete due to self-desiccation without moisture exchange to the ambient atmosphere. In cement pastes with w/c-ratios < 0.40, consumption of water by the hydration results in a reduction of internal RH. As a consequence of the drop in RH, the attractive surface forces between C-S-H particles (mainly capillary and disjoining pressure) grow and the distance of the solid surfaces decreases.

1.3 Influence of ground limestone on the shrinkage of cement paste and concrete

Different factors regarding the quality of the ground limestone – as aggregate or binder – influence the drying and autogenous shrinkage of hcp and concrete [6]. In cement paste and concrete containing high limestone contents, the amount and the chemical-mineralogical characteristics of limestone can have significant impacts on the shrinkage behaviour [11]. Higher limestone content resulted a larger drying shrinkage deformation for self-compacting concrete with the same water content [12]. Esping showed that the higher BET-surface area of limestone leads to a higher autogenous shrinkage of self-compacting concretes [13]. In concrete made with high limestone contents, the clay-contaminated limestone can remarkably influence the shrinkage behaviour of concrete. Clay minerals can also enter into concrete through clay-contaminated aggregates or fillers that have been studied more in the literature. Many fresh and long-term properties of concrete can be influenced by the type of clay mineral [14–16]. An increasing effect of clay mineral on the drying shrinkage of cement paste and concrete is reported in [17–19].

1.4 Aim and procedure of the study

In this study, drying shrinkage and autogenous shrinkage of clinker-reduced hardened cement paste (hcp) and concrete made of limestone-rich cements were experimentally investigated. The focus was mainly on the drying shrinkage as the dominant shrinkage type for concretes made of limestone-rich cements. Although the magnitude of the irreversible shrinkage deformation is crucial in practical application, in this paper the total drying shrinkage (sum of reversible and irreversible deformation) at the first drying cycle was analysed. Essential was the understanding of the contribution of different physical and chemical-mineralogical properties of ground limestone as main cement component to the drying shrinkage deformation of hardened cement paste and concrete.

2 Experimental program

2.1 Raw materials

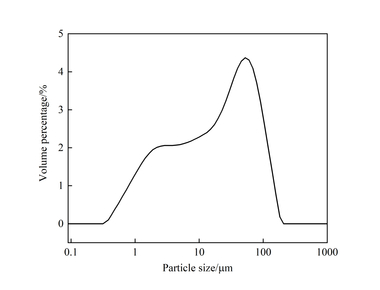

Limestone-rich cements were prepared in a laboratory scale by mixing an ordinary Portland cement CEM I 52.5 R (clinker > 95 wt.-%) and various contents of different limestones. In this paper, the clinker is assumed to be the same as CEM I for calculating the water-clinker-ratio (w/k-ratio). Fourteen limestones LL1, LL2a, LL2b, LL2c and LL3-LL12 from several German quarries and with different chemical-mineralogical compositions were used. Limestones had CaCO3 contents above 66.9 wt.-%. It should be mentioned that limestones LL2a, LL2b and LL2c are from the same quarry (similar chemical-mineralogical properties) but have different Blaine finenesses. Chemical and physical properties of the CEM I and the limestones usedare presented in Table 1.

2.2 Sample preparation

Cement pastes and concretes (with designation indices P and C, respectively) were produced by mixing cement (CEM I + limestone) and water in a Hobert mixer according to DIN EN 196-1. The ingredients were mixed with a combination of low and fast speeds for an overall duration of about 6 minutes to ensure a perfect mixture of cement with water, especially at low w/c-ratios. In order to prevent segregation of the cement paste mixtures with high w/c-ratios (0.70 and 0.60), the mixtures were rotated in polyethylene bottles for a maximum of 5 hours with a constant rotation rate (1 rotation per 10 min).

2.3 Mix proportion

Cement pastes with different contents and types of limestone were produced. Reference cement paste and concrete samples with different compressive strengths were cast with CEM I at four w/c-ratios of 0.70, 0.60, 0.50 and 0.35. Cement paste and concrete made of cement with 50 wt.-% limestone (CEM (50% LL)) and w/c = 0.35 were proposed as the target mixture [3], hence the main focus was on this limestone content and w/c-ratio.

Concrete mixtures with similar composition to the hcp samples were cast to investigate the influence of content and chemical-mineralogical properties of limestone on the drying shrinkage. The volume of the cement paste and the maximum aggregate size were 420 ± 5 l/m³ and 8 mm, respectively. The overview of the mix proportion and the investigation parameters is presented in Table 2.

2.4 Test methods

The compressive strength of the hcp and concrete samples were measured at the age of 28 days according to DIN EN 196-1. Hardened cement paste (hcp) and concrete samples were stored in water for 27 and 6 days, respectively. The drying shrinkage measurements were carried out by means of an extensometer with an accuracy of 0.001 mm on 10×40×160 mm³ hcp and 40×40×160 mm³ concrete samples at T = 20 ± 1 °C and RH = 65 ± 3%. Two samples were cast for each mixture. Specimens were demoulded after one day and the measurement points were glued on two surfaces of each specimen just after demoulding (a total of four measurements). The autogenous deformation was measured on 40×40×160 mm³ cement paste specimens under sealed conditions in accordance with DIN 52450.

3 Test results and discussion

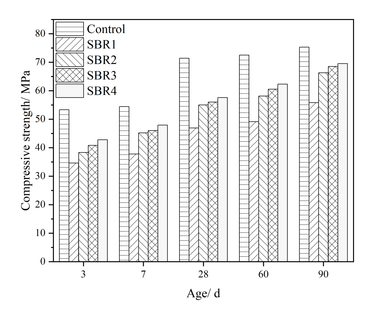

3.1 Compressive strength of cement paste

The results of the compressive strength of the investigated hcp samples are shown in Figure 1. It is visible that the compressive strength decreases for samples made of CEM I when the w/c-ratio increases. At a constant w/c-ratio of 0.35, an increase in the limestone content led to a significant reduction of the compressive strength. Samples made of cements with 30, 50 and 70 wt.-% limestone exhibited similar compressive strengths compared to reference specimens with CEM I and w/c-ratios of 0.50, 0.60 and 0.70, respectively. Comparison of the results for hcp samples with 50 wt.-% revealed that the influence of the type of limestone on the compressive strength is not very remarkable, where specimens exhibited a compressive strength of 46 ± 5 MPa. The sample made of limestone LL5 with a significant lower CaCO3 content exhibited the smallest compressive strength of about 41 MPa. Nevertheless, it can be seen that at a given w/k-ratio, samples containing limestone exhibit higher compressive strengths compared to the reference samples made of CEM I.

3.2 Drying shrinkage of cement paste

3.2.1 Introduction

Because of an unproportioned difference between shrinkage deformation of some samples during drying, application of the measured shrinkage values at an arbitrary age might not provide a reasonable judgement about ultimate shrinkage behaviour of the samples. In this paper, under the assumption that the autogenous shrinkage will be almost negligible after 6 days of water storage, the extrapolated ultimate drying shrinkage εds,∞ was used for interpretation of the results.

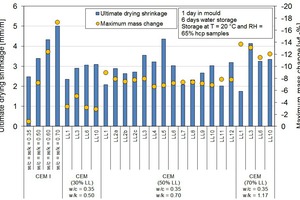

3.2.2 Influence of content and chemical-mineralogical properties of limestone

The results of the ultimate drying shrinkage and the maximum mass change of hcp samples made of CEM I and cements with different limestone contents are shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that the drying shrinkage and the mass loss of the cement pastes made of CEM I are strongly dependent on the w/c-ratio. Results obtained for hcp samples with limestone-rich cements reveal a notable influence of the content and the type of limestone on the magnitude of the drying shrinkage. For example, an increase in the content of limestone LL1 resulted in a reduction of the drying shrinkage, whereas inverse results were obtained for samples made of limestone LL3. It is visible that at a given limestone content, the shrinkage deformation is remarkably affected by the type of the limestone, while the drying mass change was mainly controlled by the content of limestone (at constant w/c-ratio of 0.35) and was not affected by the chemical-mineralogical composition of the limestone. Comparison of the results obtained for cement pastes made of limestones LL2a, LL2b and LL2c reveals that the drying shrinkage is not affected significantly by the fineness (Blaine value) of the limestone.

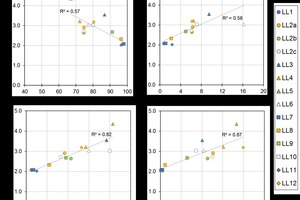

The correlation between ultimate drying shrinkage and different chemical-mineralogical properties of limestone are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen in Figure 3a that shrinkage deformation increases as the CaCO3 content of limestone decreases. This indicates that present impurities of limestone lead to a higher shrinkage deformation. Furthermore, a proportional contribution of the BET-specific surface area of limestone (SSABET) towards the increase of drying shrinkage is visible in Figure 3b. Both higher specific surface area SSABET and the MB value of limestone can be attributed to the presence of clay minerals. A higher correlation between MB-value and drying shrinkage (R² = 0.82) existed in comparison to SSABET (R² = 0.58). Since the MB value represents the amount of clay minerals in limestone, the increase in drying shrinkage can be attributed to the shrinking clay minerals. Swelling clay minerals exhibit a higher disjoining pressure. The type and concentration of cations in the pore solution as well as the density of surface charge are the main factors influencing the magnitude of the disjoining pressure by altering the repulsive hydration component [20]. Because the alkali oxides in limestone can be independent from the presence of clay minerals, it can be deduced that both shrinking clay minerals and alkali oxides affect the drying shrinkage of hcp independently. Understanding the exact contribution of each of these parameters requires additional experiments which are under investigation within a separate research project.

The correlation between ultimate drying shrinkage and compressive strength of the hcp samples is illustrated in Figure 4. It evidences that all samples containing limestone have more or less lower shrinkage compared to the reference samples made of CEM I. The maximum variation of 27 % in the drying shrinkage was observed for samples with a compressive strength of about 65 ± 5 MPa with 30 wt.-% limestone. However, this variation was about 110 % and > 130 % for average compressive strengths of 55 and 25 MPa corresponding to the samples with 50 and 70 wt.-% limestone, respectively. These results reveal that there is no systematic correlation between the magnitude of the drying shrinkage and the compressive strength, if the type of limestone, i.e. chemical-mineralogical properties, is varied.

3.3 Autogenous shrinkage

The autogenous shrinkage at 112 days was used as the ultimate value. The results of the autogenous shrinkage of hcp samples made of CEM I and cements with different contents of limestone LL1 and LL3 are illustrated in Figure 5. It evidences that autogenous shrinkage increases as the w/c-ratio decreases. Independent from the limestone type, an increase in the content of limestone results in a reduction in the autogenous shrinkage under sealed conditions. A slight swelling deformation was observed for hcp samples made of 50 and 70 wt.-% limestone LL3 at w/c = 0.35. The reason for swelling which is known as autogenous swelling can be attributed to the re-adsorption of the excessive water (at high w/k-ratios) by the hydration products and the swelling clay minerals [21].

3.4 Shrinkage of concrete

The results of the drying shrinkage – as the dominant shrinkage type – of concretes made of limestone-rich cements are shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that similar to the results obtained for hcp, the drying shrinkage of concrete samples is significantly dependent on the properties of the limestone. Meanwhile, it is visible that concretes with limestone exhibit smaller or equal drying shrinkage deformation compared to the reference concrete made of CEM I with a similar compressive strength.

Figure 7 shows that there is no general correlation between compressive strength and the drying shrinkage of concretes with different limestone qualities. For instance, the drying shrinkage decreases as the compressive strength reduces for concretes made of limestone LL1, while an inverse behaviour was observed for concretes made of CEM I and limestone LL3.

4 Potential transfer to practice

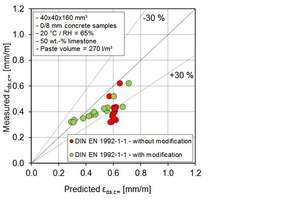

As Figure 7 showed, a variation of more than 90 % in the drying shrinkage deformation (relative to the lowest value) exists at a compressive strength of about 60 MPa for concretes made of cement with 50 wt.-% limestone at w/c = 0.35. These findings are in contradiction with prediction models such as DIN EN 1992-1-1 or fib Model Code 2010 that predict the same drying shrinkage for concretes with a similar compressive strength and cement type. Therefore, the applicability of these models for concretes made of limestone-rich cements with different chemical-mineralogical characteristics is in question. A model to predict the drying shrinkage of concrete made with limestone-rich cements is developed in [22].

A simplified recommendation is proposed to adapt the shrinkage model of DIN EN 1992-1-1 regarding the concretes with high limestone contents according to equation (1) (see also [11]).

εcd0,mod = εcd,0 · βL⇥(1)

In the above equation, εcd,0 is the basic drying shrinkage according to DIN EN 1992-1-1 and modification factor βL considers the content and the chemical-mineralogical properties of limestone according to Table 3. Due to the fact that cements with limestone contents more than 35 wt.-%.-% are not regulated by EN 197-1 yet, calculation of shrinkage when limestone is considered as the main cement component is not possible. Therefore, the limestone was considered as concrete addition and CEM I 52.5 R is considered as cement component with (class R with original αds1 and αds2 according to DIN EN 1992-1-1).

This approach shows a reduction in the drying shrinkage compared to reference concretes for most application cases. For example according to Table 3, a limestone content of 50 wt.-% and a typical MB-value of 0.3 g/100g (CaCO3 ≈ 90 wt.-%) yields to a calculated shrinkage reduction of about 30 %. Comparison of the measured and calculated drying shrinkage of concretes with cement paste volume of 270 l/m³ according to DIN EN 1992-1-1 with and without modification in Figure 8 reveals a good accuracy of the proposed approach.

5 Final conclusion and outlook

Based on the test results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1. At a given water/clinker-ratio, hardened cement paste (hcp) and concrete samples containing limestone could exhibit a higher compressive strength than reference samples made of pure Portland cement (CEM I). However, these mechanical parameters were not affected significantly by the chemical-mineralogical composition of limestone.

2. The drying shrinkage was identified as the dominant type of shrinkage for hcp and concrete samples made of cements with high limestone contents ≥ 50 wt.-% and water/cement-ratio of 0.35. At such limestone content, the contribution of the autogenous to the total shrinkage deformation was observed to be insignificant.

3. Drying shrinkage of hcp and concrete made of limestone-rich cements was strongly dependent on the chemical-mineralogical properties of limestone. Within these properties, the MB-value and the alkali oxide content of the limestone were identified to be the most dominant parameters.

4. Concretes made of limestone-rich cement exhibit smaller or equal drying shrinkage deformation compared to the reference samples made of CEM I with a comparable concrete compressive strength and cement paste volume. The reduction was more remarkable for samples made of limestones with high CaCO3 contents of > 95 wt.-%.

5. Further investigations are required to understand the exact contribution of alkalis to the drying shrinkage of hardened cement paste as well as the influence of ITZ characteristics on the shrinkage behaviour of concretes with high limestone contents.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the German Research Foundation (DFG) for its financial support.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.