Segregation of bulk solids –

causes and solutions

In many processes, individual steps involve the presence of bulk solids as the primary, intermediate or end product, and the individual particles can cover a size range encompassing eight powers of ten. The flow behaviour of bulk solids, however, depends not only on the size of the particles, but also on their shape and density and, not least, on the moisture content of the material. In certain applications, it is not only important to ensure reliable flow, i.e., to avoid flow obstructions, but also and primarily to prevent segregation.

1 What causes segregation?

Segregation becomes a problem when downstream processes require that the bulk solid be of uniform composition. This is the case, for example, when the product is to be packaged in portions of identical composition (sales packages or the like), or when a downstream process could become unstable if the product composition were to vary.

Bulk solids tend to segregate, if the particles differ in terms of size, shape or density. Bulk solids with very poor flow behaviour, such as very fine-grained titanium dioxide, or which are too moist (e.g., moist clay) normally show...

1 What causes segregation?

Segregation becomes a problem when downstream processes require that the bulk solid be of uniform composition. This is the case, for example, when the product is to be packaged in portions of identical composition (sales packages or the like), or when a downstream process could become unstable if the product composition were to vary.

Bulk solids tend to segregate, if the particles differ in terms of size, shape or density. Bulk solids with very poor flow behaviour, such as very fine-grained titanium dioxide, or which are too moist (e.g., moist clay) normally show little tendency to segregate, because the dominant adhesive forces restrict the mobility of the particles. By way of contrast, free-flowing bulk solids, as well as cohesive bulk solids that are easy to fluidize on exposure to gas flow, frequently undergo distinct segregation.

Segregation has many causes. Diverse mechanisms are known from pertinent literature (see [1, 2] for an overview), but they cannot always be reliably distinguished, since they often occur in combination. The key effects, as described below, apply not only to large silos, but just as well to all other containers and hoppers (e.g., hoppers of bag filling machines) into which bulk solids are filled.

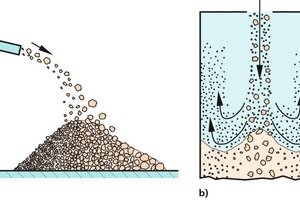

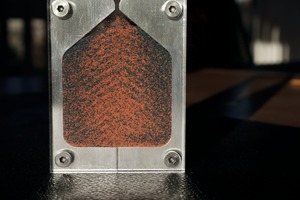

1.1 Segregation on inclined bulk solid surfaces

When a bulk solid is filled into a bin or poured onto a heap, it forms an inclined surface at a certain angle of repose – unless it has been fluidized and will therefore require a substantial length of time for deaeration. The bulk solid lands at the highest point of the heap and flows down along the inclined surface (Fig. 1). If the particles are of non-uniform size, the sifting effect shown in Figure 1 a will have the greatest impact. The surface of the bulk solid will have the effect of a sieve, because the small particles will fit easily into the spaces between the larger particles, where they come to rest while the large particles find too few or no appropriate voids and therefore continue to flow down along the slope (A short film depicting this type of segregation is shown in [3]). Consequently, this type of segregation produces an accumulation of fine particles around the point of impact of the feed stream (e.g., in line with the silo axis in case of straight-down filling from above), while the coarser particles tend to collect closer to the wall.

The inclined surfaces of bulk solids also promote segregation when different constituents of a given bulk solid have different natural angles of repose. In Figure 1b, for example, the angular particles in the bulk solid have a steeper angle of repose than the round particles. The latter are unable to stop rolling down the steeper slope and therefore travel on out to the perimeter of the heap. The larger the round particles, the better they roll down the slope [4]. The situation shown in Figure 1c is similar. In this case, cohesive forces enable the fine-grained particles to adopt a steeper angle of repose than that of the larger particles [2].

If the bulk solid only contains only few large particles being considerably larger (and heavier) than the fine particles, they may cause craters to form on impact. The craters, in turn, trap the large particles, leading to a higher concentration of coarse material at the centre of the heap. Any large particles that happen to pop out of their respective crater will tend to roll all the way down to the base of the slope. In this case, coarse material will be found to have accumulated both at the top centre of the heap and around the bottom [5, 6].

Mass flow rate also plays a role. The greater the mass flow rate, the thicker the layer of material sliding down the inclined surface. This makes it more difficult for the fine and coarse particles to separate within the available length of time. Consider the surface-filtration effect (Fig. 1a), for example, where thicker layers of material sliding down the inclined surface would leave less time for fine particles to settle out along the way, thus causing them to continue on toward the base of the heap.

Segregation due to the sifting and to differences in the natural angle of repose for particles of different shape depends on the particles being sufficiently mobile. In other words, it does not tend to happen to bulk solids with poor flow properties. This type of segregation can be expected both for dry bulk solids with particle sizes beginning at roughly 100 µm, and for moist bulk solids showing adequate flow behaviour despite their moisture content (e.g., wet gravel sized 5 to 10 mm will segregate anyway, because the adhesive forces are of secondary importance). Segregation according to Figure 1c or due to cratering can occur in the presence of very fine fractions. However, no precise particle size limits can be defined, because other parameters such as the breadth of the particle size distribution or the shape of the particles are also involved. Remarkably, segregation can be observed for particle size ratios as small as 1:1.3 [7].

1.2 Percolation

When a given volume of bulk solids is deformed, e.g., when it flows, small cavities form between the individual particles, leaving room for small particles to enter and occupy. This is referred to as percolation. In most cases, thanks to the force of gravity, the fine particles tend to migrate downward, hence gradually displacing the larger particles toward the surface [2, 8]. The sifting effect on the inclined surface of the heap shown in Figure 1 a is attributable to percolation: The small particles entrained in the layer of bulk solids sliding down the inclined surface penetrate, i.e., percolate, into cavities situated at the surface of the heap.

Percolation also occurs when a bulk solid is vertically shaken or subjected to vibration. As a (large) particle moves upward due to vertical oscillation, it leaves behind an empty space, into which smaller particles tend to migrate. Consequently, when the particle “tries” to move downward during the subsequent phase of oscillation, it is no longer able to regain its original position and will therefore remain an increment higher than before. As the larger particles gradually ascend, the smaller particles eventually collect at the bottom of the container. Also referred to as the Brazil nut effect (cf. simulation [9]), this granular convection phenomenon can, under certain conditions, also lead to the accumulation of large particles at the bottom of the container [10].

1.3 Segregation by influence of the gas phase

The trajectories of particles moving through a gas (air) are distinctly influenced both by the force of gravity and by flow resistance, or aerodynamic drag. The smaller the particle, the greater its resistance to flow in relation to its gravitational force as well as to the kinetic energy it possesses at a given velocity. Consequently, the (steady-state) settling velocity of such particles in the field of gravity declines along with the particle size (Fig. 2).

Similar behaviour is found if a stream of particles is initially directed horizontally, e.g., when discharged from a belt conveyor.. The smaller the particles, the more their horizontal motion component is retarded. In other words, the smaller the particle, the closer to the point of discharge it will fall.

Such effects already become significant for particle sizes of 50 to 100 µm and are particularly pronounced for particles in the sub-10 µm range (Fig. 2). This means that very small particles can move only slowly relative to the suffounding gas and are therefore easily influenced by the flow of the surrounding gas (e.g., air currents).

The following typical segregation phenomena derive from the influence of the gas phase:

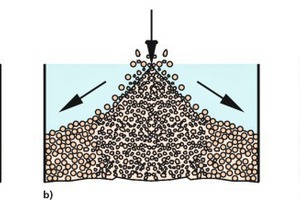

If a bulk solid is discharged with a horizontal velocity component (Fig. 3a), the larger, heavier particles will decelerate less quickly than the smaller, lighter particles due to aerodynamic drag, and therefore travel farther. This results in segregation at the point where the material comes to rest, e.g., on a heap like that shown in Figure 3 a or inside of a side-filled silo.

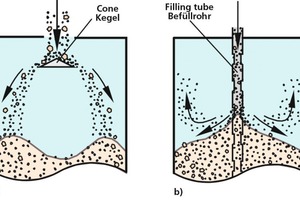

If a bulk solid is filled into a silo from above (Fig. 3b) sufficiently large particles drop quickly and collect at the centre of the heap, while the finer particles (reference value: < 50 … 100 µm [5, 12]) are pushed aside and even partly carried upwards by the flow of gas deflecting off of the surface of the heap. Sometimes, very fine particles are seen to adhere directly to the wall of the silo, where they form an increasingly thick layer that eventually separates from the wall by reason of its own weight. The aforementioned gas flow consists either of conveying air from the pneumatic filling system or of the air stream dragged by the particle stream.

In the case of a dense stream of bulk material less segregation can be expected, because the trajectories of the particles situated within the stream of material remain largely unaffected by aerodynamic drag [5].

Vertical segregation occurs when the bulk solid includes large quantities of readily fluidizable fine particles with substantial air retention capacity. During the filling process, such material forms a level, fluidized layer of material at the surface of the silo content, through which the larger particles descend [1, 2, 13]. At the end of the filling process, the fluidized bulk solid settles and forms a surface layer consisting largely of fine-grained material. Thus, batchwise filling produces successive horizontal layers containing a “glut” of fine particles interspersed with layers containing an elevated share of coarse material. In contrast to all other described forms of segregation, this variant is of a vertical nature.

2 Means of preventing segregation

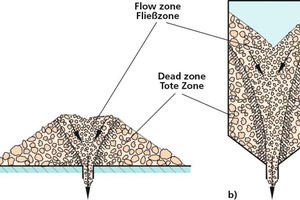

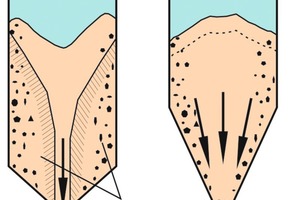

If the material became segregated at the time of filling or piling, it will show when the bulk solid is extracted. When material is extracted downward from the centre of a conical heap (Fig. 4a) a flow zone forms above the outlet, and the bulk solid situated above that point discharges first. The same applies to the silo in Figure 4b, because its hopper walls are not sufficiently steep, resulting in funnel flow [1, 14].

There are three ways to counter segregation. The first is to alter the product itself in order to make it less susceptible. This approach involves:

Narrowing the particle size range or, in case of bulk solids containing different components, equilibrating the particle size distributions.

Reducing the flowability in order to make the particles less mobile and, hence, less able to segregate. This can be achieved by either adding moisture or reducing the particle size. On the other hand, this would also make the product more susceptible to flow problems.

For mixtures of different components: granulating the material such that it contains all components in the desired concentrations. While this approach does shift the mixing problem to a different process, it also prevents the subsequent segregation of material stored in bins.

Experience shows, however, that such measures are usually too expensive to implement. Therefore, an alternative means of avoiding segregation is often applied to the filling process. Here, a number of different measures can be taken, including the following selection (see [1] for an overview):

Distributing the filled-in bulk solids over a wider area, e.g., by means of a conical distributor or similar fitment (Fig. 5a). This prevents the formation of a central cone that would promote segregation along its slope. Nevertheless, cross-sectional segregation can still occur (ring-shaped pile with segregation on its slopes, different trajectories).

Distributing multiple inlets over the roof of the silo to help level out the surface of the bulk solid. The main problem in this case, however, is how to get the bulk solid divided into multiple streams of identical composition.

Filling by means of a vertical tube with side openings (Fig. 5b: filling tube). This way, the bulk solid stream stays together and may even be slowed down as it emerges from the pipe, but a sloped heap will still result, and fine particles will still become entrained in the upward flow of air.

In case of pneumatic conveyance: bulk solid is not blown into the silo but separated from the conveying air just above the silo (e.g., in a cyclone separator) in order to reduce air flow within the silo.

Installing a helical slide at the centre of the silo to keep the particles from falling freely, so less segregation due to airflow entrainment can be expected.

In case of segregation due to a fluidized layer of bulk solid (see 1.3 above) a device assisting deaeration may help. This could consist of vertically vibrating bars extending down through the bulk solid [2]. This option is rather expensive and therefore only suitable for small bins.

All such measures have some degree of influence on material segregation during filling processes, but the question remains as to whether the overall effect would suffice to achieve adequate mixing quality [1]. Experience shows that these ordinary measures do not necessarily produce satisfactory results (e.g., [15]). Consequently, the only way to effectively reduce segregation in most cases is to design the silo or hopper for mass flow.

The term mass flow, in contrast to funnel flow (Fig. 6a), means that there will be no dead zones in which the sum of the material being extracted remains in place until most of the rest has been discharged. In a mass flow discharge process, all of the bulk solids stay in motion from the beginning to the end of discharge (Fig. 6b). For mass flow to be achieved, the hopper walls must be steep enough to prevent the occurrence of dead zones. The requisite slope angle can be determined on the basis of the measured flow properties, especially in terms of wall friction [1, 14]. It is also important that the feeder withdraws the bulk solid from the entire outlet section, that there are no inward-projecting rims, and that the silo/hopper has only one outlet opening [1].

Under mass flow conditions, the bulk solid exits the silo in roughly the same succession as it had at the time of filling (first in - first out). This results in a narrow residence time distribution which becomes narrower with increasing ratio of silo height to diameter. Filling-induced cross-sectional segregation is reduced by the fact that the segregated portions of the silo content are reunited in the hopper. For example, the coarse material from the outer zone and the fine particles from the inner zone blend back together (Fig. 6b).

Experience shows that providing for mass flow is the most reliable way to reduce segregation (see [15] for a practical example). Even that option, however, is of limited efficiency in the case of bins with a too low height-to-diameter ratio, because differences in flow velocity remain unavoidable despite mass flow conditions in the hopper [1]. Nor is mass flow of much help in countering vertical segregation due to fluidization of the bulk solid (cf. end of section 1.3 above), because the horizontal layers with different compositions tend to exit the silo in succession.

3 Conclusions

Whenever a given bulk solid contains particles of diverse size, shape and/or density, material segregation must be anticipated. The observed effects can differ from one plant to the next and as a function the properties of the bulk solid. Designing the bins, hoppers, silos, etc. for mass flow has proven itself to be the most effective means of reducing segregation, because it ensures that the bulk solid exits the silo in roughly the same succession as at the time of filling. Thus, components that became segregated during the filling process are re-united in the hopper.

Topical seminar

The topics discussed in this paper will also be dealt with at this year’s annual GVT seminar “Vom Schüttgut zum Silo” (From bulk solid to silo) in Braunschweig. The upcoming seminar is scheduled for 22/23 February 2016. For more information, go to //www.gvt.org" target="_blank" >www.gvt.org:www.gvt.org. Seminar language is German.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![2 Steady-state settling velocity of spherical particles (calculated according to [11] for Re < 0.25 “Stokes law”)](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_fe17ac61bb44e33d661bc7a3cfe1b0eb/w300_h200_x400_y295_101549723_202d0f9ccf.jpg)