New polymorphous CaCO3-based cementitious materials

Part 2: Calera – a technology assessment

“Green cements” with the potential to significantly reduce CO2 emissions are still in the focus of attention in the cement industry.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

While two recent reports [1, 2] investigated Novacem, a magnesia-based product technology, this paper continues a study on Calera, another approach using mineral sequestration to produce cementitious materials. Antetype for its production is the formation of corals and sea shell by bio-mineralization.

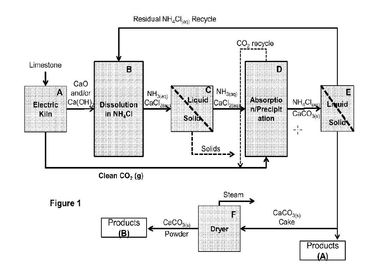

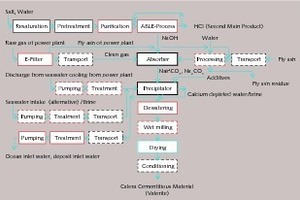

In Part 1 [3], Calera was introduced as an approach originally devised 2007 by researchers from Stanford University. The basic principle is to sequester CO2 from coal or natural gas power plants into the metastable mineral vaterite, an anhydrous modification of CaCO3. Part 1 especially focused on the resource base of the Calera process. Different sources for calcium chloride were presented: On one side, sea water and salt lakes/brines, on the other side produced water from oil or gas fields. Beside on these resources, emphasis was given to alkalinity that is required for the process. Alkaline brines, especially digestions of coal fly ash are favored by Calera. Additionally, Calera developed its own technology to secure the alkaline feedstock, the ABLE (Alkalinity Based on Low Energy) process to produce caustic soda [4, 5].

Part 2 focuses on detailed process flows of Calera technology. All steps are described to estimate the potential or bottlenecks for large-scale realization. Based on this, energy- and CO2-balances are presented that help to assess how far Calera has the potential to lower CO2-emissions.

2 The manufacturing process of Calera™ – a model

Flue gas supply

Alkalinity supply

CO2 capture (absorption)

Brine/seawater winning and supply

Vaterite precipitation/settling

Dewatering/drying

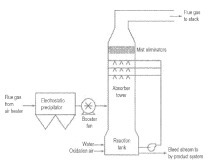

In principle as an absorbing technology a scrubber column, a spray column, or a planar liquid jet reactor can be used. In the Calera pilot plant at Dynegy’s Moss Landing (California/USA) a spray column is in use, probably to produce CaCO3 and MgCO3. In a next process step the alkaline Na2CO3-solution is mixed with an aqueous solution of Ca and additives which yields in the precipitation of solely CaCO3 (vaterite) when adjusting the pH-value. After the settling of the precipitate a mechanical dewatering is done. The subsequent drying process delivers the final product.

Using these specifications and our own plausible assumptions for further process steps, a coherent process chain was set up, which depicts the production of these cements under commercial conditions. We have modelled a continuous operation to produce 100 000 tons of vaterite taking into account conditions for large-scale technical realization (Fig. 2).

In this context, some operation steps like absorption, precipitation and separation seem to be quite complex to be realised for large-scale application. The absorption technology should be able to produce saturated Na2CO3-solutions to limit the generated volumes. The heat of reaction could support this procedure. For absorbing CO2, we use a counter flow absorber which we think would yield good absorbing rates. Precipitation and separation have to deal again with huge amounts of very dilute solutions of calcium. Common technologies use settling tanks (Fig. 3) as an established apparatus when magnesia/magnesite is extracted from seawater. This procedure can possibly be applied for the vaterite production. According to a Calera patent, long sett-ling times (several hours) cannot be excluded. Whether strainers could be alternatively applied for large-scale application, as Calera has implemented on a small scale at the Dynegy’s Moss Landing pilot plant, cannot be clearly answered.

To demonstrate material flows and cumulated energy requirements, we combine the model plant with a 200 MW coal power plant for CO2 supply. Many coal-fired power plants in the USA are operating so far with stack temperatures in the range of 150 °C [9], e. g. for avoiding fouling and corrosion due to sulfuric acid condensation. Calera uses this waste heat in its technology. For this investigation, a modern plant was chosen because in a long-term view all power plants (in the USA as well) will be energetically optimized for sustainability reasons [9] and all considerations should be valid for these plants too. Selected parameters of operation of the coal power plant and the model production plant are shown in Table 1. For the production of 13.3 tons of vaterite per hour, an amount of 5.9 tons of CO2 per hour has to be supplied and therefore separated from the flue gas. This accounts for 4 % of the total CO2 emissions of the reference plant.

As calcium resources, we discuss two contrary cases: In case 1, sea water is in focus, Calera’s initial vision, an approach which is still not explicitly rejected. We assume that Calera technology can use the discharged seawater before it is released to the ocean, similar to desalination plants which are adapted to power plants for cooling the heat generating section. However, the use of seawater as resource could be hindered by U. S. Regulations in future [10, 11]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is in the process of issuing standards for the use of cooling water at existing U.S. power plants to reduce the environmental impacts from once-through cooling. Seawater cooling systems can negatively affect organisms in the aquatic ecosystem. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that seawater for Calera technology must be extracted separately which is optionally included in the balances. Fig. 4 shows a global map of selected costal coal power plants (< 10 km distance from coast). Manufacturing sites which are more than 10 km away from the source are likely to be economically inappropriate. In this variant it is assumed, that pipelines are not longer than 1 km and that the technological conditions are comparable to the manufacturing of magnesia/magnesite from sea water, as demonstrated in Figure 3.

Case 2 is focussed on produced water resulting from oil and gas production with relatively high Ca-concentrations of approximately 20 g/l. Such concentrations in brines would certainly be suitable in respect to mass application. However this is probably rather an upper limit scenario, because such concentrations are only available at selected locations.

One risk of the Calera technology is the amount of alkalinity necessary for the process: For each ton of CaCO3 generated, 0.34 t of hydroxide (OH-) must be provided. In our model calculations, two options for alkaline supply are taken into account: the use of coal fly ash (option 1) and the use of caustic soda (NaOH), the latter delivered by the ABLE process (option 2). As demonstrated in Part 1 [3], on the average 5-6 kg of coal fly ash is theoretically needed to supply the amount of hydroxide necessary for the precipitation of 1 kg CaCO3. But under real conditions, a higher amount of fly ash as assumed is necessary since the alkaline oxides are also available inert, incorporated in different glassy and crystalline phases.

At locations where alkaline waste and brines are not available, Calera tries to generate its own alkalinity feedstock (NaOH) using the ABLE technology. In difference to the current chlor-alkali process Calera states that the ABLE technology would be capable of delivering caustic soda with significant lower energies [12]. Calera stated 2011 at the ecra-conference in Barcelona that the theoretical cell voltage is about a third (0.83 V) of that of the chlor-alkali process [7]. It can be assumed, that the real cell voltage is higher because of losses. Because of lacking information, for a first approximation an efficiency rate of 40 % for technical application is taken into account. On the basis of estimated 1.16 V for cell voltage, about 777 kWh have to be provided for the production of one ton NaOH using electrolysis, this corresponds to 621 kWh for precipitating one ton of CaCO3. As stated in a Calera patent [4], the brine used must be purified. For this purpose, purification similar to conventional membrane cell technology can be supposed. According to the IPPC, about 120 kWh per ton of NaOH additional energy is required [13].

After processing, the depleted water probably cannot be fed back to the sea unprocessed. Control of the pH-value is necessary to avoid undesired effects at the location. Further on, depending on source of alkalinity used in Calera technology, the liquor potentially contains ingredients (heavy metals, trace elements) which require additional pollutant control.

Significantly higher electrical demands (768-813 kWh/t) arises in option 2, where NaOH is used as alkaline source; this approach seems more realistic to us. Even if NaOH is manufactured within a low energy technology, the energy balance is totally determined by the electrochemical process. A partial allocation of the energy to the second main product HCl is not acceptable, because there will hardly be any economic market. Implementing the ABLE technology for mass application of Calera cementitous materials (millions of tons or more2) would produce large amounts of HCl that have to be disposed of costly. As shown in Table 4, the total primary energy demand of vaterite would double the primary energy demand of OPC (about 4000 MJ/t).

The CO2 balances (Tab. 6) show that negative (CO2 reducing) balances are possible if the alkaline supply is based on the use of suitable waste. As already stated for the energy balance, this positive effect for the environment is possibly in contrast to negative effects, caused by trace element mobilization and transfer. In contrast, in a first approximation the sole use of NaOH in the Calera technology would balance the amount of CO2 sequestrated in vaterite from the power plant. This poses the question of whether it would be worth the effort under these conditions. Calera has the challenge of further lowering the energy demand of the electrochemical process.

3 Discussion and perspective

The challenge Calera has to master particularly concerns:

the absorption of CO2 at high separation rates,

the controlled selective precipitation and separation of calcium from dilute aqueous sources which often also contain magnesium, an element excluded so far by the cement standards,

the energetic efficient supply of large volumes of alkalinity,

the fact, that cement and natural limestone are low value-added mass products,

the proof that metastable vaterite/aragonite has suitable properties in the long-term.

We have compiled material-, energy- and CO2-balances which show significant differences to estimations of other evaluators [15-17]. Under common framing conditions and for widespread application the results in this paper indicate that the energy and CO2-balances are not so favorable. In this context, Calera deals with basic conditions which assume energetically non-efficient power plants and a non-efficient waste management. However, under optimized conditions utilizable heat for drying processes is hardly available and waste should be reused with the best option of re-utilization with regard to sustainability and economic efficiency. Calera is in competition with other options for utilization of waste energy and resources and it has to be proved that their strategy is superior to other approaches.

As demonstrated, the type of alkaline source significantly affects the energy balances. Since energy must only be counted for allocation and transport, alkaline industrial waste has mostly a limited potential of alkalinity, besides its locally restricted availability. Conflicts with other options of industrial re-utilization – possibly more economical and ecological – cannot be excluded. A substantial issue could be the regulated use of coal fly ash as hazardous material. Worldwide, there is a long established use of qualified coal fly ash in the construction industry as concrete additive or as filling material in earthwork, road and landfill construction. In some countries the use is strictly controlled by national standards. This trend will grow in future. Using higher contaminated fly ash in large amounts enhances the potential risk of unwanted environmental effects and implies an elaborated pollution control. This is also valid with regard to CaCl2 sources like production water from oil and gas which are contaminated by pollutants and which have to be managed carefully. In this context cement might potentially be used as a sink for trace elements. This wouldn’t be consistent with the label “green cement” and would counteract efforts of cement producers to improve the image of cement.

Therefore, the main emphasis for the alkaline supply may be placed on NaOH for realistic conditions. Implementing the ABLE technology for mass application - like cement as a construction material - would raise a significant HCl-problem: HCl would be produced in such large quantities, that no realistic demand could cope with it. The annual global production of HCl is currently about 20 Mt/a. By far, most of all HCl is consumed inhouse by the producer. The open world market size is estimated at 5 Mt/a [18] (Fig. 5).

Looking back at the controversial discourses in the 80s and 90s of the last century concerning the chlorine problem due to its effects on the environment, such pushing of a chlorine-product in the economic and environmental cycle would foil the international consensus to restrict the use of chlorinated products. An utilization of HCl/chlorine in such large extents could possibly generate unforeseeable environmental risks.

The approach of Calera is in contradiction with geo-engineering concepts to strengthen the CO2 capacity of the ocean. Climatologists and oceanographers have been looking for ways to counteract acidification of seawater, because acidification affects the CO2 buffer capacity of the oceans negatively. The marine calcium cycle is linked with processes that control oceanic alkalinity and the ocean’s capacity to absorb atmospheric CO2; it has an important influence on the earth’s climate. It is suggested to generate soluble calcium and magnesium bicarbonates in an autoclave, pass them to the ocean to increase the alkalinity of seawater, and thus increase its CO2 binding capacity [19, 20]. This approach has significant advantages compared with mineral sequestration because instead of one CO2 molecule now two molecules of CO2 can be fixed in seawater for each earth alkali-ion. According to recent studies, the ocean calcium cycle is more fragile than expected [21]. Changing the calcium cycle not only affects the climate. In addition, it could have potentially far-reaching consequences for marine ecosystems. The impact on the biota (e.g. plankton, shellfish, corals) cannot be finally evaluated [19]. However, it is well known that calcium-accumulating organisms such as mussels, sea urchins and corals are very sensitive to changes in the aragonite (calcium carbonate)-saturation of sea water and its acidity [22-24]. Therefore, locally or even wider unwanted effects on the marine ecosystem cannot be excluded when the calcium household changes.

An important issue for the discussion is to realize that cement is a low value-added mass product (40-70 €/t), therefore the manufacturing costs should be as low as possible. Since the strength values of CaCO3 cements might be relatively poor [25], vaterite has to be either compared with milled limestone, which is used as the main constituent in Portland limestone cements. For milled limestone we roughly assume an energy demand less than 20 kWhel/t limestone for all electric operations from quarry to silo. Raw material processing costs including “value of the limestone quarry” were estimated to be less than 8 €/t CaCO3. This means that milled limestone is a product of very low value. Comparing CEM II A/B-LL cements with corresponding vaterite-based blends (Table 6), according to our calculations the estimations of total CO2 emissions indicate no significant differences, which means that CO2 emissions associated with the production process can compensate for those sequestrated in vaterite.

There is much experience regarding how limestone impacts cement performance, how it participates in the hydration reactions of clinker and in the production process, especially the inter-grinding of clinker and limestone. Only special selected limestone fulfills the required properties. However all these issues are unknown concerning cementitious systems based on vaterite/aragonite. An important issue is the proof of durability of vaterite/aragonite cementitous materials. In this context, the behaviors concerning freeze-thaw and sulfat resistance (thaumasite formation) have to be considered. As in the case of limestone, the interaction of vaterite with concrete admixtures must be taken into account. First results on compressive strength data of concrete were presented provisionally by Calera for ASTM tests including ASTM C 1157 – “Standard Performance Specification for Hydraulic Cement and its products”. But the acceptance of this performance-based standard is not widespread among state regulatory authorities in the USA [26].

In this context, innovations in the construction materials sector face high barriers when regarding the interrelated great quantity of norms and standards. Even minor adjustments in the composition of the main constituents of cements go along with intense and time-consuming testing procedures, that precede the modification of existing norms. In this context, a significant innovation barrier for Calera as partial cement substitute is that up to now cements comparable to European Portland limestone cements are not licensed in prescriptive standards (ASTM C150) in the USA. Even the introduction of new main constituents in OPC based cements always faced resistance by potential users, due to durability and security the as main requirements in the construction sector. How far the construction sector with its norms and standards is in fact receptive to such radical innovations is questionable. Of course, this argument counts for other more radical innovative approaches as well.

To summarize: Vaterite is not an alternative for Portland cement clinker. Whether vaterite is suitable as “Partial Cement Substitute” cannot be adequately answered due to a lack of information. The fact, that vaterite is metastable produce skepticism. As shown in this paper, the realization of the vision to produce a low cost material which sequesters more CO2 than that which is released during production faces serious barriers. Regarding the large-scale realization and the availability of suitable resources, serious challenges have to be mastered. Especially if supplied in large amounts, all the suggested resources involve considerable risks.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![5 World consumption of HCl (estimated 20 million t) for the year 2008 [18]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_d1e7a013bcdd22c08ec9d63bfd820c9c/w221_h155_x110_y77_101535377_6f0c55a250.jpg)