New calcium hydrosilicate-based cements: Celitement – a Technology Assessment

Green cements with the potential to significantly reduce CO2 emissions are still in the focus of attention in the cement industry. This paper outlines the approach of Technology

Assessment and the research design, gives a brief overview of the binder characteristics of Celitement technology (calcium hydrosilicates) and discusses the resource availability. A model of a plausible manufacturing process of Celitement is given, followed by a discussion of the corresponding balances. Finally the paper summarizes the implications which can be derived from the perspective of Technology Assessment and innovation research.

1 Introduction

It is generally agreed that radical reductions of CO2 emissions cannot be realized maintaining the paradigm of traditional clinker production. Even more efficient combustion technologies, rising shares of traditional clinker substitutes and more efficient process technologies are not sufficient to meet reduction targets, even those of the Cement Sustainability Initiative [1, 2]. End-of-pipe technologies like CCS are still discussed as an essential part of the solution within the cement community [3]. This may raise false hopes for solutions in the distant future whose technical...

1 Introduction

It is generally agreed that radical reductions of CO2 emissions cannot be realized maintaining the paradigm of traditional clinker production. Even more efficient combustion technologies, rising shares of traditional clinker substitutes and more efficient process technologies are not sufficient to meet reduction targets, even those of the Cement Sustainability Initiative [1, 2]. End-of-pipe technologies like CCS are still discussed as an essential part of the solution within the cement community [3]. This may raise false hopes for solutions in the distant future whose technical and economic feasibility is unknown yet [4], not to mention problems regarding public acceptance [5].

In the last decades, a common strategy was to substitute the clinker in cement by using latent hydraulic residual materials like ground blast furnace slag or coal fly ash (CFA). However, the potential for their use in Europe is largely exhausted to date [6]. On a global scale, there are indications that fewer amounts of CFA are applicable for cement production than commonly assumed [7]. Furthermore almost all synthetic latent hydraulic materials originate from thermal technologies and therefore cause a significant ecological footprint. Depending on the mode of allocation with regard to the production process, the resulting footprint can be even larger than that of clinker.

Within the research community many scientists agree – although favoring very different solutions to the problem – that major steps to reduce the emissions are only possible if progress in the development of alternative clinkers is realized [8, 9, 10]. However, a sophisticated solution to substitute OPC as a universal binder has not yet emerged. Preliminary examples are belite calciumaluminate cements [11] and cements using impure clay which contain not only kaolinite but also montmorillonite or illite as the main constituent [12]. The former proceeded in the direction of cements for special applications, not feasible for general construction tasks [9]. There are also indications that kiln operation to sinter belite calciumaluminate cements may be challenging due to a narrow temperature window [11]. A disadvantage of cements using calcined clay as a constituent is that such clay minerals must undergo thermal activation to receive pozzolanic activity. With regard to this activation considerable R&D efforts are still necessary until a technically feasible solution may be found. Whether the entire process will be economically viable for mass application cannot be sufficiently answered yet.

Recently the cement community has been confronted with some more radical developments coming from outside the traditional cement community. They are based on completely different technology approaches compared to conventional cement production and raised remarkable attention in both industry and politics. Prominent examples are (a) Novacem, an invention based on special MgO systems which was introduced by researchers at the Imperial College London [13], (b) Calera cementitious materials developed by the Calera Corporation in Los Gatos, California, originating from Stanford University [14], and (c) Celitement, a development of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology [15].

Novacem and Calera are dealing with CO2 mineralization [16], sequestrating anthropogenic CO2 into minerals. Both approaches are labeled carbon negative by the inventors, trying to sequestrate more CO2 than is being emitted during manufacturing. Novacem proposed a binder system based mainly on magnesium silicate hydrates (M-S-H) when hardened. Calera is mimicking bio-mineralization, equivalent to the formation of corals and sea shells, and produces a binder consisting of vaterite, a calcium carbonate (CaCO3) polymorph. Celitement, in turn, consists of a new family of calcium hydrosilicates (h-CSH) of low calcium content1.

All these inventions are labelled as a break-through and a possible solution to the CO2 problem of cement production. Indeed, all of these approaches attracted investors, and startup enterprises were founded. In the case of Novacem and Celitement these were supported by established cement companies2. This indicates that the cement industry takes these inventions seriously. Calera is an enterprise backed by Koshla Ventures. A pilot plant in Moss Landing was funded between 2007 and 2011 and a large research group established. Despite these efforts it became remarkably quiet in recent years with regard to CaCO3-cements. However, the initial founder Brent Constantz still proposes the vision of cements or aggregates from his proprietary process [17].

Due to media intensive campaigns and numerous awards, expectations in politics and the cement industry were raised with respect to the practical feasibility of these inventions. In particular, the question arises, whether the inventions really have the potential to substitute considerable quantities of conventional cement. No in-depth estimations of the economic and technological feasibility have been provided by the inventors so far. We aimed to fill this gap with a Technology Assessment (TA) of these inventions to prove their respective innovation potential. Detailed results of systems analytical investigations on Novacem and Calera were already presented by the authors [7, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Following these assessments, we now present a first analysis of Celitement in this paper. Research focused on the availability of raw material resources, the conditions for large-scale technical realization, and energy-balancing.

2 Methodology and approach

Assessing the feasibility of a technology in the early beginning of its development is a difficult challenge. Particularly the lack of detailed internal knowledge hampers the use of standard assessment methods. Details of the invention are often not revealed by the inventors and process developers in order to avoid potential competition. Only sometimes is well-grounded knowledge available from scientific papers or what is presented on conferences. In most cases, information has to be taken from different sources like newspaper articles, magazines, press releases or interviews. Such information is often imprecise or even inconsistent. Therefore it is difficult to build up a coherent picture based on these diverse sources.

Besides the lack of knowledge and due to the early state of development, there is often a high degree of uncertainty related to the actual path the technological realization might take. In many cases the development is still at laboratory level or at best of pilot plant scale and one has to deal with the difficulties of up-scaling the approach to a technical or even industrial level (which can be an insurmountable obstacle for the inventors themselves). Moreover, first steps towards commercialization are often accompanied by new knowledge and insights from the labs, which then question the decisions already taken and lead to ongoing uncertainties and alterations.

From its beginning in the 1970s Technology Assessment (TA) developed methods to deal with such a lack of knowledge and the uncertainties associated with new technologies [22]. TA initially aimed to inform policy makers on risks, chances and unintended side effects associated with emerging technologies, providing sound scientific background for the political decision-making process. Beyond advising politicians, other variants of TA are closer to the technology development. These cover methodologies for prospective assessments for early engagements at the planning, laboratory or pilot plant level. The aim is to assess the conditions of realization, the economic potential, the chances, and risks associated with the new technology as early as possible3. While such work is commonly associated with the approach of Life Cycle Analysis (LCA), accompanying TA follows a different approach. Since LCA tools draw on standardized data sets, LCA is often not suitable for such cases where technology developments are still at their very early stage of development. TA instead generates the basic data, e.g. for guiding ways to the technical realization itself with adequate accuracy. For the assessment of new cements, a viable method is to derive a material flow analysis identifying all relevant chemical or material transformations to build up a coherent conversion string from the raw materials to the end product (cement). Gaps have to be closed by plausibility considerations and rough estimations. The string is then transformed into a process chain by identifying all relevant basic process operations taking into consideration the production capacity of the anticipated plant. Calculations are carried out at an adequate depth for the specified task. Suitable or commonly used system components and even alternative solutions are evaluated and further specified, with particular emphasis on energy efficiency and economically sound solutions. As a result, a plausible model of a possible technical realization can be drafted. This is conducted in an iterative way to allow for feedback and ongoing interaction with the developers to improve the technology at early stages of a development process. The energy balances used for modelling rely on thermodynamic and chemical methods, including realistic efficiency estimations. Further, for the analysis of resource use and availability, geochemical, chemical, and mineralogical aspects have to be considered and available technologies for extraction of material along the supply chain have to be investigated.

Since 1997 a workgroup of the Institute of Technical Chemistry (ITC) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) is investigating the cement chemistry of C-S-H-gels. These activities led to the development of a new class of low CO2-binders in 2006, which form the basis for Celitement. Mostly unperceived by the broader cement technology community, patents were filed in 2005 and 2007. In 2009, the start-up Celitement GmbH was founded as a private limited company in collaboration with the SCHWENK group. Two years later, a pilot plant was launched at the KIT campus with a daily production capacity of 100 kg. For this study basic data of the Celitement pilot plant were used as a starting point. The annual capacity of the modelled plant amounts to 15 000 tons of autoclave product. It is important to keep in mind that solutions for a technical realization of certain process steps in our model may differ from those used to design a real pilot or reference plant. This allows for evaluating alternative solutions for fundamental process steps, e.g. how the heating of the autoclave can be realized, or how residual energy occurring along the process chain can be recirculated.

3 Binder characteristics of Celitement

An important characteristic of traditional OPC is that approximately 50 % of the limestone used is calcined without contributing to the later formed CSH-components which are responsible for final strength development. Thus from the view of strength development, energy consumption and CO2 emissions are at disproportionately and in principle unnecessarily high levels in the clinker manufacturing process4. During cement hydration, besides the formation of C-S-H, the other half of the cement is transformed into secondary products such as calcium aluminate hydrates and calcium hydroxide, which have a lower mechanical strength compared to that of C-S-H. The molar CaO/SiO2 ratio within the starting calcium silicates is the controlling parameter. If this ratio equals or exceeds 2, calcium hydroxide (portlandite) is always formed during hydration:

Ca3SiO5 + 3 H2O ➝ Ca1.7SiO3.H2O + 1.3 Ca(OH)2⇥(1)

Ca2SiO5 + 2 H2O ➝ Ca1.7SiO3.H2O + 0.3 Ca(OH)2⇥(2)

In other words: about 2 kg of OPC are needed to obtain one kilogram of C-S-H, if a molar CaO/SiO2 ratio of 1.7 within the C-S-H is assumed for the freshly formed solid solution [23]. Results of Garbev et al. [24] imply that even 2.5 kg OPC paste have to be hydrated to obtain 1 kg C-S-H.

The aim of the KIT research was the development of an effective hydraulic binder based solely on calcium silicat which reacts as completely as possible to C-S-H during hydration. This implies that the CaO/SiO2 ratio in the binder has to be well below the factor of 2. The production of such binders is not possible in conventional kilns where the main phases produced would consist of minerals such as rankinite, pseudowollastonite, or wollastonite, which have no significant hydraulic activity. Therefore, a radical new approach was developed based on the interim phases suggested to be formed during the formation of C-S-H. With regard to the existence of such intermediate phases and the initial reaction processes of calcium silicates in contact with water, the cement research community is divided. The state of research has been firstly summarized by Taylor [23]. According to Taylors model, an intermediate phase is initially formed in a very rapid reaction during hydration of alite. Taylors theory has attracted much attention and forged a number of new studies. Other theories have been put forward which challenge Taylor’s theory and the formation of an intermediate phase [25, 26]. Indirect evidence of such intermediate phases was obtained by KIT researchers who identified layers of a few nanometer thickness during hydraulic reactions of the clinker minerals alite and belite [27]. Other researchers also found hints of an intermediate C-S-H phase with a quite small CaO/SiO2 ratio [28, 29]. But up to now, no direct evidence for the existence of such temporarily formed species exists.

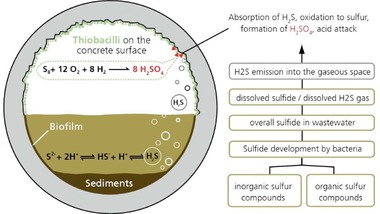

According to Stemmermann et al. [15] the interim species mentioned above can be considered to be calcium hydrosilicates (h-CSH). It was possible to develop a technology to stabilize these species and to use them as binders. Structural elements of the proposed h-CSH are known to exist in several phases in the system CaO-SiO2-H2O under ambient and hydrothermal conditions. In the KIT laboratories two routes for synthesis have been established using (a-C2SH) or nearly amorphous C-S-H phase with the idealized formula Ca5[HSi2O7]2 ∙ 8 H2O (C1.25-S-H). Both materials can be synthesized from Ca(OH)2 and quartz by fine grinding and processing them for 6 hours at around 190 °C in an autoclave. The product consists of up to 90 mass % of calcium silicate hydrates. A strong system of hydrogen bonds in the structure is responsible for low hydraulic reactivity of these species. Structural disorder is necessary to transform a-C2SH and C1.25-S-H into a hydraulic reactive state. A promising way to introduce structural disorder is mechanical milling (tribomechanical activation). The mechanical activation of a-C2SH or C1.25-S-H can be performed within a mill with or without quartz or another silica-carrier (e.g. blast furnace slag) as core (core shell approach): the actual adhesive, i.e. new hydraulic calcium hydrosilicates, is formed on the surface of the interground silicates. The product family has the idealized formula C1.25[HSiO4]y[H2Si2O7]z with C/S = 0.75-2.75 [30] The hydration of these h‑hydrosilicates can be observed using cryo-electron microscopy (Figure 1). After some hours all calcium hydrosilicate grains are coated by C-S-H. The pore volume between the grains shows successively fine patterning. After 7 days, the sample looks ceramic [31].

4 Resources for the Celitement technology

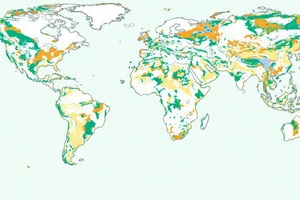

When developing alternative mineral binders, there are strong arguments to remain within the well known C-S-H-system. Firstly, extensive experience is available within the system CaO-SiO2-H2O including minor elements such as Al2O3 and Fe2O3. Even in the case of traditional cements basic chemical processes may not be fully understood yet, but knowledge is still large compared to the complex chemistry of totally new binder systems. Secondly, the calcium-carrier limestone is one of the earth’s most common mineral commodities and therefore a rather abundant mineral (see Figure 2). Relying on the compositional range of the C-S-H-system implies that the resource availability remains nearly unchanged in comparison to that of conventional cements. Limestone used for cement manufacturing is mainly a marine sedimentary rock. Its extraction and pretreatment is well-established and economically predictable.

Industrially produced slaked lime (CaOH)2 and finely ground quartz (SiO2) are currently the starting materials for the autoclave step within the Celitement technology. Slaked lime is produced by adding water to burned lime (CaO) mostly in a continuous hydrator. During this process heat is released and the unslaked lime doubles its volume. There are many possible designs of the technical apparatus necessary for lime production and slaking. The technology is well-established and details can be found in the respective literature. Since limestone is the raw material for producing slaked lime, the Celitement technology uses nearly the same basic resources as are required for the manufacturing of conventional cement and aerated concrete, respectively.

Quartz (SiO2) is one of the most common minerals found within the Earth’s crust (see Figure 2). It occurs in nearly all mineral environments and is a significant component of many igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks. Sand and gravel are mined world-wide and account to the largest volumes of solid material extracted globally. Sand was until recently extracted in land quarries and riverbeds; however, a shift to marine and coastal aggregates has occurred due to the decline of inland resources. Formed by erosive processes over thousands of years [32], in some regions sand is now being extracted at a rate far above its renewal. Due to the rapid economic growth in Asia [33] the amount being mined is increasing exponentially. Negative effects on the environment are inevitable and can be seen worldwide. Generally, sand from deserts cannot be used for concrete production, as the wind erosion process forms round grains which do not bind sufficiently [34]. On the other hand, with regard to the use in hydrothermal processes this is not a limiting factor.

In the following some specific issues regarding quality requirements for the raw materials will be discussed. While the quality requirements for slaked lime within the Celitement technology are relatively low, the material requirements for the quartz sand may be of greater relevance. In general, the reactivity of quartz is very low and conversion rates are slow. Since this issue is essential for producing e.g. aerated concrete or sandstone, particularly for high-end applications, quartz must be mechanically, thermally, or chemically stressed. Grain size, specific surface, and order/disorder within the crystallinity of quartz may be important issues. Depending on the quartz sand available the effort for activation may vary considerably.

Due to the discussed environmental impacts, geographic distribution, and special quality requirements, other silica-carriers (e.g. slag, granite, basalt) were also investigated in the context of the Celitement technology. In order to reduce the embodied energy of the raw materials and the autoclaving time it would be advantageous to use pure calcium silicates, e.g. belite as a starting material. Thus slaking and the associated energy consumption could be avoided. A low temperature process for the industrial production of calcium silicates, mainly belite, from natural sand and limestone, suitable as raw material for the autoclaving step in the production of h-CSH has been subject to further investigation at KIT. A variety of different limestone and siliceous raw materials was tested. A related patent was filed [35].

5 The manufacturing process of Celitement –

a model

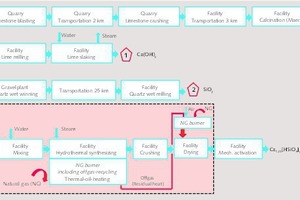

The assessment of the technical feasibility and the estimation of energy- and CO2-balances are based on considerations using a model plant with an annual production capacity of 15 000 tons of the autoclave product. In the following assessment only a product with a final C/S ratio of 1.25 is discussed. The presented balances do not take any silica-carrier as grinding partner into consideration. All balances are calculated assuming [1.25 Ca(OH)2 · SiO2 · 0.9 H2O] as autoclave phase. A coherent process chain was established using data of the pilot plant with a focus on a possible technical realization (Figure 4). Although the Celitement technology currently uses slaked lime and quartz as starting materials in the pilot plant, our balances include the extraction of these materials as preliminary chains. Besides these pre-steps, the total process route involves 4 main stages: The delivery and calcination of limestone, the slaking of lime, the hydrothermal synthesis of (C-S-H)-phases, and the tribomechanical activation.

The relatively small production capacity of the model plant suggests the integration of this plant into an existing cement or lime producing facility. This allows sharing of preliminary steps (e.g. quarry, limestone crushing) and infrastructure (e.g. limestone transport), and includes the allocation of corresponding material flows and emissions.

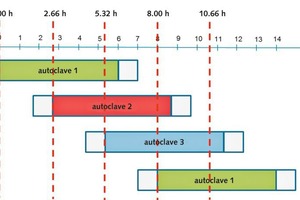

The process chain starts with the extraction of the raw materials from quarries and gravel plants. Limestone is calcined using BAT technology (e.g. Maerz kiln) for producing lime which is slaked in a next step. It is planned that quartz is delivered by truck from an external gravel plant and finely ground at the future Celitement production facility. Slaked lime and quartz powder are mixed with water and are hydrothermally treated with steam within the autoclave at operation conditions mentioned in chapter 3. For the calculation of these balances it is assumed that three autoclaves are correspondingly clocked which allows a quasi-continuous operation (Figure 5).

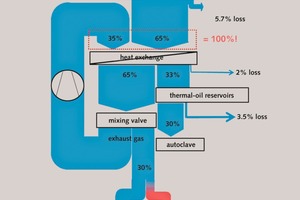

Due to the low operation temperatures of the main process steps, we preferably suggest the use of thermal oil for heating the autoclave which would allow higher energy efficiencies. The use of pure steam for heating proves to be energetically ineffective. Further energetic improvements can be obtained by recirculating parts of the exhaust gas of the natural gas burner. According to our model calculations, 35 % of the energy demand can be covered by the exhaust gas (see Figure 6). The autoclave product is crushed and afterwards dried within a drum dryer. Since the autoclave process yields some usable residual energy, this is taken into account within the drying process. Finally, for modelling the mechanical activation a two-stage ball mill, selected by the authors as one feasible model approach, was taken as a basis.

5.1 Energy and CO2 balances – discussion

The results presented now are the outcome of a careful analysis of a plausible technical realization of the described process chain. It is conducted based on currently available interim results of the development at the pilot plant at KIT and own approaches, taking into account energy efficient and economic solutions for each system component. Table 1 shows the thermal and electrical energy demand and CO2 emissions summarized for relevant process steps. The thermal energy demand is estimated to amount for 60 % of the conventional production of OPC. Although the calcination of limestone is still dominating the thermal energy demand, the quantity of CaO needed is significantly lower. The process steps of hydrothermal synthesis and mechanical activation (grouped to “Celitement” in Table 1) account for the main contributions of the total energy demand. Approximately 90 % of the electrical energy demand is currently caused by the mills. The total CO2 emissions of the Celitement process are clearly less than those of OPC production. This can be achieved without involving alternative energy carriers and renewable raw materials with “zero”-emissions within the balances. It should be noted that at several points along the process chain a considerable amount of residual heat is available, whose use within the process chain is currently not optimally assigned. By adding a significant amount of silica carrier to the activation milling energy consumption and CO2 emission are potentially further reduced.

6 Conclusions and outlook

The modeled plant design and the presented balances give a snapshot within the ongoing process of developing and optimizing the Celitement technology to industrial scale, not claiming to represent a final result for an industrial reference plant. To keep the complexity of the balances manageable, the plant design was based on a small capacity approach. Nevertheless, from the perspective of Technology Assessment the following implications can be derived regarding the Celitement technology:

First, the analysis of the complete process chain shows that this technology is feasible for the plant size considered within this Technology Assessment. The process steps are mostly known from the cement and aerated concrete industry. The technical realization of the mechanical activation at a larger scale is a challenge, but possible. Up to now, no tribomechanical activation has been realized at the industrial scale typical in the construction products industry. Celitement GmbH and cooperation partners have to develop or adapt expertise for technical realization at industrial scale. Even though the conditions for further R&D in the mid-term are expected to be excellent and experience can be iteratively gained from the operation of the pilot plant (production rates of more than 100 kg/d), a stronger collaboration with e.g. mill manufacturers would be beneficial especially when scaling up for mass application. In the meantime some important steps forward have been taken in this context – without an essential influence on the properties of the resulting products.

The thermal energy demand is estimated to reach 60 % of what is needed for the production of OPC. Although the calcination of limestone is still dominating the thermal energy demand, the quantity of CaO needed is significantly lower. The process steps including hydrothermal synthesis and mechanical activation (grouped to “Celitement” in Table 1) account for the main contribution of the total energy demand. From the balances, approximately 90 % of the electrical energy demand is caused by the mills. Since electrical energy is mostly linked with high demands on primary energy (e.g. Germany: 1 kWhel = 2.71 kWprimary), the electrical energy demand for mechanical activation (milling) must be lowered in future, even for smaller plants. It should be noted that a considerable amount of residual heat is available at several points along the process chain. So far, these potential savings were not considered in this assessment but can further lower the overall energy demand significantly.

Despite the technological challenges, the total CO2 emissions of approximately 600 kg/ton Celitement are already remarkably lower compared to those of OPC; even disregarding reductions caused by the so-called core-shell approach. All this can be achieved without including alternative energy carriers and renewable raw materials with “zero”-emissions within the balances.

The findings indicate that the considered plant capacity of 15 000 tons/a of autoclave product is clearly too small with regard to technological scalability, market volume of intended applications (e.g. special binders), and profitability calculations. The minimal production capacity for a reference plant should exceed that of the model plant by a factor of 3. Compared to conventional cement production, the capital costs per ton of the considered plant are expected to be significantly higher and the thermal efficiency was assessed to be relatively unfavorable. But the overall production costs should remain comparable to those of e.g. conventional white cement.

The used resources are equal to those for conventional cement. The production of h-CSH by using the Celitement technology rests on the same raw material infrastructure as today’s cement or lime production. The current specification and focus on slaked lime and high-quality quartz sand as raw materials does not preclude alternative solutions in the long-term. Due to the limited availability of quartz sand in many regions, the use of other abundant silica-carriers (e.g. slag, granite, basalt) should be investigated for the Celitement technology. The implementation of a low temperature process for producing calcium silicates, e.g. belite as a starting material could be a promising way. A patent of a technology, which allows the use of a variety of different limestone and siliceous raw materials, has already been granted. A Technology Assessment of the integrated technology will be provided by the authors in the future. On the other hand it is already clear that such an integrated approach is only suitable if it is implemented in technologies for mass production processes like aerated concrete production or Celitement technology. A huge advantage of Celitement is that the hardened binder consists of (C-S-H)-gels, which links the new binder concept to the existing knowledge stock on C-S-H phases. Although a number of public awards shifted attention to the start-up, no detailed information on products produced with and properties of Celitement, is publicly available yet. First indications regarding strength development, shrinkage and resistance to freeze-thaw cycles were published in Stemmermann et al. [15], but not updated since that time. In general calcium hydrosilicate-based cements show a lower water demand, due to the fact that they already contain some chemically bound water in the still unreacted material. Therefore, chemical additives like liqufiers are most likely needed to guarantee workability. The pore solution in Celitement “cement stone” has a lower buffer capacity because of the low calcium content and the absence of portlandite. This may have consequences on corrosion issues related to the protection of steel reinforcement in concrete applications. On the other hand the hardened binder has an extremely low capillary pore content, which should make carbonation and an attack of gas and liquid on steel very difficult [36], similar to the behaviour of ultra high strength concrete (UHSC). It should be further noted that the pH-value within the pore solution can be preset by the C/S ratio within the Celitement “cement stone”.

In spite of the technological challenges mentioned towards scaling up, the Celitement technology is currently one of the most promising and also the most advanced innovations for low CO2 Cements. The collaboration of basic research teams within a national basic research institute with an experienced cement manufacturer is the most striking difference to other radical developments. From the beginning the project was designed as a long-term collaboration. By this research activities were aligned to the requirements for basic research in construction. In a more and more competitive environment even for basic research, where research on construction materials is exposed to short-term funding and has to compete against other more publicly appreciated technologies, projects like Celitement are still an exemption rather than the rule. Currently, a large technical production plant is designed for a capacity of 50 000 tons/a5 and the market entry for high value-added products for mortars and finery is targeted, according to a recent project report [37]. The targeted year for the launch of a reference plant is 2020.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 Hydration of Celitement after 5 h, 8 h, 1 day und 7 days. The samples were broken under liquid nitrogen and examined by electron microscopy. After a few hours (above), all Celitement-grains are coated by C-S-H. After 7 days, the sample looks ceramic [31]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_72802f974523e073f19e37059236ebde/w300_h200_x400_y299_101551690_b23beca3d1.jpg)

![3 Average composition of main oxides within the earth’s crust [38]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_e9ab945eb0a38543ebfd25ac93dc4382/w203_h138_x101_y69_101551682_41e53de1c5.jpg)