New polymorphous CaCO3-based cementitious materials – Part 1: Calera – availability of resources

Green cements with the potential to significantly reduce CO2 emissions are still in the focus of attention in the cement industry.

1 Introduction

Therefore, different advanced approaches to reduce the emissions are currently in focus....

1 Introduction

Therefore, different advanced approaches to reduce the emissions are currently in focus. In addition to the controversially discussed carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, alternative binders are increasingly being developed, whose production releases significantly lower CO2 emissions compared to OPC. Some of these alternatives are based on binder concepts or developments which were already debated in the past. However, up to now they have just occupied niche applications but did not achieve any significance in market shares for different reasons. These include, for example, cements based on belite, sulfo-aluminate (SAC), calciumaluminate (CAC), and geopolymers (GP), just to name the most important ones. In recent years, new developments in the cement sector – all of which are still far from being ready for the market – have been publicly touted as the “solution” to solve the CO2-problem of cement production. Newer developments of “green cements” are e.g. Novacem, Calera, Celitement, TecEco, Greensols, Calix, or E-Crete (Fig. 1).

This investigation continues a series of reports on new binder concepts that was started recently with a systems evaluation on Novacem [2, 3]. Due to its prominent position in professional circles and in the media, the approach of Calera Corporation, Los Gatos, California [4], was selected for a systems analytical investigation.

Recently, at conferences or in reports related to carbon capture, initial comparisons of Calera with Portland cement were presented [5-7]. However, the explanations are rather superficial and in particular with regard to the theoretical CO2 saving potential only a few aspects are in focus. Topics like a comprehensive analysis of the cumulative energy expenditure, an examination of the entire process-chain, availability of resources for the new mass building material and the costs of the resource supply, conditions for large scale industrial implementation or the anticipated environmental impacts are in fact not in the focus up to now.

In this systems analysis the question is examined to what extent the Calera developments based on polymorphous calcium carbonate could have the potential to replace the mass construction material Ordinary Portland Cement. This investigation also includes a first analysis of the conditions for a large scale realisation. While in part 1 characteristics of this binder and the supply of the resources are described and assessed, in part 2 the inventions are evaluated regarding the (cumulated) energy demand of the manufacturing process, using consistent model-process chains. Additionally CO2 balances are established. To come up with our aim of assessing the potential as a mass construction material, finally the invention is evaluated according to its position in the present construction industry from the perspective of technology assessment.

2 Methodology and approach

However some useful information can be gathered from the patent specifications, from brief descriptions and presentations, and derived from expertise in cementitious binder chemistry and in technical operations. Gaps are closed by plausibility assumptions. To analyse the conditions for a large-scale technical realization and to comprise the cumulative energy expenditure and material flows, a plausible process chain of the technology must be established. These issues are performed using methods like process chain analysis, material flow analysis and energy balancing based on thermo-dynamical and chemical approaches including realistic efficiency estimations.

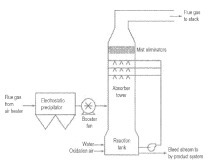

The Calera technology is based on mineral sequestration, an approach for storing CO2 from e.g. coal or natural gas power plants into disposable or even better: usable minerals like MgCO3 and CaCO3 which can be used as construction materials [9]. The cementitious material presented by Calera at the ecra conference 2011 is for example based on the vaterite polymorph of CaCO3 [10]. For this reason, all explications in this paper are focussed on modelling the selective production of vaterite (CaCO3). Potential alternatives based on the production of mixed MgCO3 and CaCO3 used as aggregate or sequestration product are not considered here.

Part 1 of this systems analysis starts by introducing the history and the approach of the Calera technology. Next, the polymorphous CaCO3 modifications and their properties known from literature are briefly presented. The focus of part 1 is the examination of the envisaged calcium resources (seawater, brines) regarding their availability and their impact on the conditions of technical realisation for a mass application. In this context, the use and availability of alkaline waste (coal fly ash) and caustic soda produced by a special electrochemical process named ABLE (Alkalinity Based on Low Energy) are investigated and evaluated. Based on the public information available, ABLE – also a development by Calera – is compared with the membrane technology of the chlor-alkali electrolysis.

Based on the present state of knowledge, in part 2 the essential steps of a plausible production process are presented [11]. We design a model for the production of 100 000 tons vaterite, because we think that this is a plausible plant capacity. Assessments of the potential material flows and the energy requirements are established, using a simplified process chain analysis for different options of the calcium content and alkalinity of the resources used. A modern 200 MW coal power plant is used as the CO2 source. These results and the estimated CO2-saving potential of the production process are compared with other already published evaluations of the Calera technology.

3 History of the Calera technology

At the ecra conference in Barcelona [10] the Calera Corporation presented their cementitious products as materials which focus on a partial replacement of clinker in cements by vaterite (CaCO3) or a “self cement”, consisting of self-cementing aragonite, composed mainly of vaterite. At the World of Concrete 2011 Calera stated that they produce about 1 ton of Partial Cement Substitute (PCS) per day [20].

4 Calera-based binders –

Polymorphous calcium carbonate

Calcite is thermodynamically the most stable modification of CaCO3 and therefore the main component in limestone. The second most common modification, which is also the densest and favoured by high pressure, is aragonite which is present in corals (Fig. 2) and nacre. Aragonite is metastable under normal conditions. It gradually alters into calcite. Mg- or Sr-ions stabilize the structure of aragonite. Mg contained in seawater favours the formation of aragonite.

Metastable vaterite (Fig. 3) is a cristalline but highly disordered anhydrous CaCO3-modification. In nature, vaterite deposits are scarce compared to aragonite und calcite. In a lab, fast precipitation in addition to high super-saturation accompanied by selective addition of additives favours the formation of vaterite. Vaterite alters quickly into aragonite or calcite. However, the presence of additives decelerates this transformation. The polymorphism of CaCO3 depends mainly on the operational conditions such as solution temperature, solution pH, feed rate of reactants, solution composition, type and concentration of additives, and mixing.

Besides this, monohydrocalcite (CaCO3 H2O) is another metastable but hydrous phase. At room conditions MHC transforms slowly into calcite or aragonite. It can also be stabilised by Mg-ions. The precipitate can contain significant amounts of Mg [22].

Vaterite is the end product of the Calera technology. This product is intended to partially replace OPC, similar to limestone as the main component in CEM II. According to Calera also a “self-cement” can be produced, composed mainly of vaterite and special additives, transforming all vaterite into aragonite when hardening during 28 days. The additives are not specified by Calera. According to Combes et al. [23] the strength values of synthetic CaCO3-cements (aragonite) are low (< 13 N/mm²). Preparation of synthetic CaCO3-based cements requires the synthesis of pure polymorphes that have to remain stable in cement compositions until final utilization. As Combes points out, the preparation of pure amorphous CaCO3-phase is complex since amorphous CaCO3 crystallises rapidly. In the absence of stabilising ions (e. g. Mg, Sr) a mixture of metastable CaCO3 consisting of ACC and some vaterite and calcite arises. Mg inhibits the formation of calcite.

5 Resources for the Calera binder technology

As shown in Table 1, the concentration of calcium in sea water is considerably lower than those of other ingredients, e.g. magnesium. Therefore, for mass production a high volume of sea water is necessary which must be considered for site selection (and for the assessment of the operation expense). In principle, each location along the sea coast can be considered for obtaining CaCO3, if a local CO2 source exists and bio-geo-marine and economic conditions are suitable.

More often than on the earth’s surface CaCl2 brines can be found subsurface, one type even in undersea formations. Most potash and some halite (rock salt) formations are associated with strong calcium chloride brines. Brines with lower CaCl2 concentrations are occasionally found in coastal aquifers, or in formation waters of oil or gas fields that have been generated from seawater. In addition, many deep sea geothermal vents contain calcium chloride.

The calcium content in natural brines varies greatly (Tab. 2) even though in some deposits liquors with high concentrations (e.g. 170 g CaCl2/kg liquor) can be extracted [30]. Natural brines account for 70–75 % of the United States CaCl2 production. Production is carried out by the concentration and purification of naturally occurring brines from salt lakes and salt deposits.

In general, the calcium content in the production waters exceeds the magnesium content by far. According to the USGS produced water database (58 000 samples), relatively low Ca-concentrations are measured at most wells (Tab. 3) [31, 34]. Just a small share of the samples shows concentrations of 20 g/l and higher. International representative values are not available to us. The International Association of Gas & Oil Producers [35] only published a value for the average global concentration of total anions of about 60.9 g/l. This seems to be in the same magnitude as the corresponding U.S. value.

Produced water from oil, gas, and coal extraction typically contains hydrocarbon residues, heavy metals, hydrogen sulfide, and boron. These hydrocarbons include organic acids, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenols, and volatiles [36]. Further on, chemical additives must be considered, which are used in drilling and producing operations and in the oil/water separation process [37]. Produced water can therefore be hazardous. There is a dispute about potential environmental impacts when releasing produced water [35, 38]. Produced water possibly requires treatment before used as resource. The processing of CaCl2 brines can be either very simple or a complex series of operations, depending on the purity required. When manufacturing cementitious materials consolute with OPC, just pure CaCl2 should be produced, especially when the substance is used as clinker substitute, because according to the cement standards magnesium and chloride are banned from cement composition.

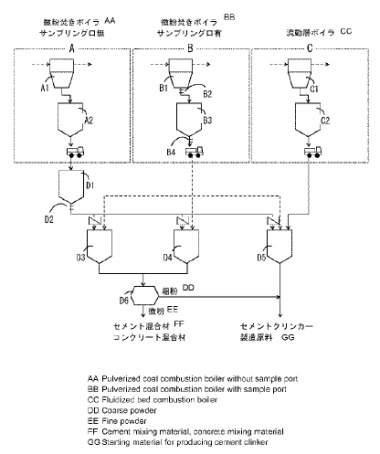

The single oxides found in fly ash can be roughly classified into basic oxides (e.g. CaO, MgO, MnO, FeO, Na2O, K2O...), acid oxides (e.g. SiO2, P2O5, ...), and amphoteric oxides like Al2O3, Fe2O3. Therefore, when mixing fly ash with water an initial pH-value can be obtained from 4 to more than 12. But not the pH-value of an aqueous solution is important, the equivalents of hydroxide (mol) is critical. The mineral phases in coal vary widely and undergo complex phase transformations during incineration which decisively influence the potential to release hydroxide during hydration. Most of the oxides are incorporated into glassy and mineral phases and are inert. The share of free oxides is relatively low. But even that share of CaO and MgO which exists as “free lime “and “free periclase” has a delayed reaction since these oxides are “dead-burned”.

Based on an extensive analysis of data of coal fly ash from different countries, it can be assumed that the total content of relevant oxides in fly ashes is approximately 10 mass-%, for ash of anthracite/bituminous coal and ca. 15 mass-% for ash of lignite. The results indicate that on average 1 kg of coal fly ash corresponds to 3.7 molar equivalents of hydroxide (63 gram of hydroxide per kg of ash). This implies that about 5-6 kg coal fly ash is needed to supply the alkalinity necessary for the precipitation of 1 kg CaCO3. Even if the total basic oxides are about 30 mass-% (e.g. 90-percentile value in the USGS National Coal Quality Inventory), about 2 kg coal fly ash have to be provided. However this is not valid because in fly ash the relevant oxides are also available inert, incorporated in different phases. Therefore, a higher amount of fly ash as assumed is required.

The aqueous solution of such large amounts of fly ash could cause negative environmental effects. Data show that especially As, Cr, Mo, Sb, Se, V, and W are readily accessible for leaching [46, 47]. Additionally, a significant transfer of trace elements in the vaterite product cannot be excluded.

Calera tries to generate its own alkalinity feedstock using a patented electrochemistry process called ABLE technology [10, 17]. Contrary to the current chlor-alkali process Calera states that the ABLE technology would be capable of delivering caustic soda with only a third or even a fifth of the energy usually used in a chlor-alkali process [50]. Calera declares they have demonstrated the continuous operation at laboratory scale and are constructing a 1-ton per day pilot system at the facility in Moss Landing (California/USA). There is no information about how well-engineered and how stable the electrochemical processes are in the long-term for a scaling-up. We assumed this to be a major challenge.

The ABLE process has been developed to electrolyse NaCl to NaOH and HCl (not to Cl2 gas!). It consists of a three-compartment membrane cell configuration (Fig. 7). Essentially, hydrogen generated from the water reduction reaction occurring at the cathode is recirculated to the anode for hydrogen oxidation. Overall, theoretically 0.83 V is required to generate NaOH and HCl in comparison to 2.2 V (without over potential and losses) when using conventional chlor-alkali technologies. According to Calera, it would be possible to decrease the theoretical cell voltage further towards a laboratory scale [50]. However, at the ecra conference in Barcelona 2011 Calera presented the ABLE technology with the theoretical cell voltage of 0.83 V [10]. It can be assumed, that the real cell voltage is higher because of losses due to (e.g. kinetical) constraints. We assume that under large scale realisation conditions the delivering of caustic soda with the ABLE technology with lower than a third of the common energy demand is a challenge.

6 Conclusions

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![3 Vaterite seed crystals [21]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_15148f7ec7097ab0043c0db8851f8bcc/w300_h200_x400_y269_101534023_539e047d50.jpg)

![4 Main distribution areas of salt lakes [24]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_0826e68334e5091b5fe17daf2da1adb0/w300_h200_x400_y218_101534060_4a12079b51.jpg)

![5 Location of oil and gas wells in the USA. Average total dissolved solid (TDS) content of produced waters from oil and gas wells as indicator for calcium, magnesium and alkali [33]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_ab8a2e39cfc4bb5d9fd201557cc19d36/w300_h200_x400_y283_101534037_e85aa480f2.jpg)

![6 Equivalents of hydroxide (mol/kg) theoretically available in coal fly ash, calculated for 1501 samples of coal fly ash [45]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_20663d77c630bb1b91de060c8fa58fec/w300_h200_x400_y278_101534061_af22d0b46a.jpg)

![7 Calera’s ABLE process for NaOH and HCl production [6]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_4f3c5d84ee888037c0f5982c10ff1dfa/w300_h200_x158_y144_101534054_c705dbd726.jpg)