Trends in power generation from waste heat in cement plants

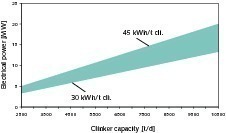

Summary: The generation of power from waste heat in cement plants was for a long time the subject of controversial discussion. Today, hardly anyone remains unconvinced by the concept. Depending on the system used, 30–45 kWh/tclinker can be generated, which is up to 30 % of the electrical power requirement of a cement plant. The benefits of this technology are clear. As electricity and energy costs increase, the plants become more and more cost-effective and the CO2 emission situation provides additional incentive. This report presents an overview of the technology and system vendors, indicates the reference systems and describes the market prospects.

Japanese companies spearheaded the introduction of Waste Heat Recovery systems (WHR) in the cement industry. In 1980, Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) put a WHR system into operation at Sumitomo Osaka Cement [1]. The first major system, with a capacity of 15 MW, has been in operation since 1982 at Taiheiyo Cement’s Kumagaya plant (Fig. 1). This system consists of waste heat boilers for kiln and cooler exhaust air with a conventional steam circuit and subsequent steam turbine for the power generation. HeidelbergCement took a different approach. In 1999, they put the cement...

Japanese companies spearheaded the introduction of Waste Heat Recovery systems (WHR) in the cement industry. In 1980, Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) put a WHR system into operation at Sumitomo Osaka Cement [1]. The first major system, with a capacity of 15 MW, has been in operation since 1982 at Taiheiyo Cement’s Kumagaya plant (Fig. 1). This system consists of waste heat boilers for kiln and cooler exhaust air with a conventional steam circuit and subsequent steam turbine for the power generation. HeidelbergCement took a different approach. In 1999, they put the cement industry’s first waste heat recovery system using the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) process into operation at the Lengfurt plant. Instead of a water/steam circuit, this process utilizes an organic process fluid (pentane) to increase the efficiency of the low-temperature power generation.

The system in Lengfurt achieves an effective net electrical capacity of 1.2 MW or 1.13 MW, after its own electrical power requirement is deducted [2]. This covers approx. 12 % of the cement plant’s electrical power requirement. This reduces the CO2 emission by around 7,000 tonnes per year. The pilot system in Lengfurt was partially subsidized by the Umweltbundesamt (German Federal Environment Agency) and received a number of awards, including the Energy Prize of the State of Bavaria in 2002. The measured long-term availability of the system (Fig. 2) was 97.1 %, which is a high figure. Although the capital expenditure was only about € 4 million and the annual operating expenses are below € 0.1m, the amortisation period was much longer than the planned 8-10 years because electricity prices decreased steeply in the years after its installation. In the West European cement industry, the experience of HeidelbergCement from then on shaped the opinion that WHR would not be cost-effective for the cement industry.

At the time when the ORC system was commissioned in Lengfurt, more than 20 WHR systems were already in operation at Japanese cement plants. Taiwan commissioned its first system in 1990 and China in 1998. However, a decisive milestone in the marketing of WHR systems was not set until the middle of the year 2000, when several factors converged: environmental discussion (greenhouse gases), rising energy prices and the market entry of new Chinese and Indian vendors. KHI collaborated with Anhui Conch to establish Conch Kawasaki Engineering (CKE, formerly ACK) in China. Since then, practically all cement plants owned by Anhui Conch Cement have been equipped with WHR systems. Other cement companies in China and other Asian countries also invested in the technology, so that the market for such systems in Asia expanded rapidly. In China alone, over 455 WHR systems were already in operation at the end of 2009 after only 25 in 2006. But in Europe very little was happening in this field. The technology did not come back into focus in Europe until it was realized that the market was booming in Asia.

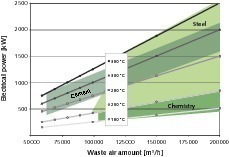

The utilization of low-temperature waste heat for generating power is by no means limited to the cement industry, as large amounts of waste heat are also utilized, for example, in the steel, paper and chemicals industries. Figure 3 depicts the typical waste air volumes and waste air temperatures in these industries and indicates what amounts of electrical power can be produced from these [3]. It shows that with a waste air volume of 150 000 Nm3/h and a waste air temperature of 300 °C an electrical power of approx. 1.5 MWel. can be generated. The problem in the cement industry is that the employed streams of waste air from the kiln and the cooler contain relatively high raw gas dust concentrations that sometimes exceed 50 g/Nm3 and that the waste air temperatures can fluctuate strongly during operation of the kiln. Furthermore, depending on the moisture content of the raw material, different amounts of heat are required for the drying or combined grinding and drying.

Depending on the number of preheater cyclone stages, the waste air temperatures from the kiln system average approx. 300-390°C, while the waste air temperatures from the clinker cooler are 250-330 °C depending on the employed cooling air volume and the recuperation efficiency [4]. In the case of a 3,000 tpd clinker production line, approx. 170,000 Nm3/h of kiln waste air and 150,000 Nm3/h of cooler waste air are produced. Figure 4 shows the MW-power ranges that can be generated by different cement plant sizes. Typically, the possible electrical power generation range, depending on waste heat losses and the number of preheater cyclone stages, is 30‑45 kWh/tclinker. If an average electrical drive power requirement of 110 kWh/tcement and a clinker factor of 0.75 are taken as the basis, then around 20 to 31 % of the required energy for the cement production process can be generated from the waste heat. In order to achieve such high power levels, waste heat boilers have to be installed downstream of the kiln preheater (PH = PreHeater) (Fig. 5) and downstream of the grate cooler (AQC = Air Quenching Cooler) (Fig. 6). The respective waste heat boilers can differ significantly as regards type of construction [5].

A typical waste heat recovery system with a conventional steam circuit consists of the PH and AQC waste heat boilers, a generator house (Fig. 7) with the steam turbine and the generator) (Fig. 8), as well as ancillary equipment such as condenser, water treatment system, boiler feed pump and recooling system (Fig. 9) [5-7]. A state-of-the-art waste heat boiler is divided into zones with condensate preheater (economiser), evaporator and superheater [6] in order to recuperate the highest possible amount of energy from the waste air and to simultaneously produce superheated steam with a temperature above 300°C and approx. 15-20 bar while reducing the waste air to stack temperature or to a temperature of 210°C for the combined grinding and drying process. To improve the achieved degree of efficiency, two-stage or multistage steam turbines are being increasingly employed. These obtain high-pressure steam from the PH waste heat boiler and low-pressure steam from the AQC waste heat boiler.

The leading manufacturers of WHR systems using conventional steam circuit technology are now marketing 2nd generation WHR systems with higher supercritical steam parameters and thus with better efficiencies. These can generate the desired 45 kWh/tclinker or even more. To assist the generation process attempts have been made to achieve higher waste air temperatures, for example by installing a bypass for one preheater cyclone stage or a waste air extraction point at the centre of the cooler [5, 8]. Despite such measures, steam circuit systems without an auxiliary firing system still have the disadvantage that the temperature gradient between the source of heat and the heat sink is relatively low. As a result, the steam in the turbine can only expand until it reaches a temperature of approx. 100 °C, when it condenses at atmospheric pressure. This correspondingly limits the efficiency of the system.

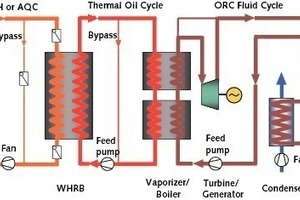

The ORC process makes use of an organic working medium such as butane or pentane instead of steam. These media have a significantly lower evaporation temperature than water as well as a high vapour pressure and thus enable the achievement of higher efficiencies in the low temperature range below 350 °C in comparison to steam [9-12]. Figure 10 is a simplified flow chart of the ORC process for waste heat utilization in a cement plant. Heat extraction at the waste heat boiler is effected by a thermal oil circuit. The thermal oil heats a second circuit in which the organic working medium is converted into vapour, which then generally drives a 2-stage turbine that generates the power. At the end of the process a cooling circuit recools the circulating working medium. The ORC process involves a more complex system than is the case with a water/steam circuit.

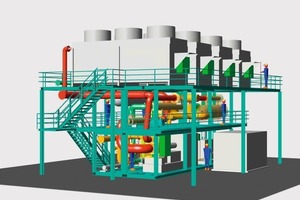

One variant of the ORC process is the Kalina process, in which a water-ammonia mixture is employed as the working medium. In the low-temperature range this process achieves the highest efficiencies. In the cement industry, the Kalina process has up to now only been tried out in pilot installations. However, concepts have shown that, especially in the case of relatively low waste air temperatures and smaller plant capacities, the ORC process provides advantages due to the compact construction of the system (Fig. 11) and are cost-effective. The working media are long-lived, there is no need for demineralization of system water, the service life of the system is in excess of 20 years and no system operators are required. In the meantime, ORC systems have come into widespread use at geothermal power stations and on the combined heat and power generation sector. Such systems are considered to be technically mature and have high availability rates.

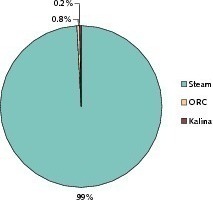

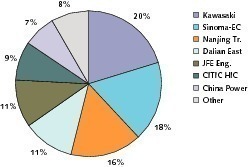

In the cement industry, 525 WHR systems were already in operation or under construction by the end of 2009. This figure is based on the number of installed power generators and not on the number of installed waste heat boilers, which was around 870. Figure 12 shows that 99 % of all installed systems use conventional water/steam circuits. So far, the Kalina process has played no role and the ORC process is also hardly represented, in spite of the advantages claimed. It follows that all of the current TOP suppliers (Fig. 13), out of a total of over 20 firms, sell the conventional process. All in all, 15 vendors sell conventional systems, 7 companies supply ORC systems and 3 firms sell Kalina systems. There is relatively little overlapping, although some cement plant engineering firms like FLSmidth, Polysius and KHD offer various processes, as does Siemens. Pure subsuppliers of waste heat boilers, steam turbines and generators are not included in the list.

Kawasaki (KHI and CKE) had supplied 106 WHR systems with a total electrical capacity of 1,413 MW up to the end of 2009. Of these, 82 systems are installed in China, 12 in Japan and three each in Taiwan, Thailand and Pakistan. The company’s market position improved significantly when it started supplying systems for Anhui Conch. In effect the collaboration began in 1996 with a first project for Anhui Conch arranged by the Chinese national planning commission and the Japanese NEDO and the greatest highlight so far has been the CKE Joint Venture. 31 systems (the first at the Ningguo plant Figure 14, and the most recent in 2009 at the Zhongguo plant Fig. 15) had already been put into operation up to the end of 2009. In March 2011, the number of WHR systems owned by Anhui Conch has already reached 43. On average, each system generates 34.25 kWh/tclinker. Several of these systems achieve values > 45 kWh/tclinker. The average operating time of the systems is 98 % of the kiln production time.

Place 2 in the ranking is taken by Sinoma EC (EC = Energy Conservation) with 92 systems supplied to the cement industry up to 2009 and a capacity of approx. 1,100 MW. The company’s most important references include orders from Lafarge in China and from the Siam Cement Group in Thailand (Fig. 16). Sinoma EC recently booked three new orders from Turkey. These involve WHR systems for Akçansa (16 MW), Batiçim (12 MW) and Batisöke (6 MW). Nanjing Triumph Kaineng (NTK) is No. 3 in the ranking, with 82 systems, followed by Dalian East New Energy Development (DEE), who had supplied 59 systems (Fig. 17) by the end of 2009. Last year, DEE concluded a cooperation agreement with Polysius. The remaining place is taken by JFE Engineering of Japan, who state that they have already supplied 55 WHR systems for the cement industry.

The other important suppliers to the cement industry include CITIC HI with its 45 WHR systems (Fig. 18) and over 90 waste heat boilers, and China Power. Taken together, the remaining vendors account for 43 systems up to 2009. Among the most important companies in the group selling conventional systems are TESPL (Transparent Energy Systems Pvt. Ltd) (Fig. 19), who – like several other firms are simultaneously designer and manufacturer, Thermax India and the turnkey system vendors FLSmidth, Polysius and CNBM. Other engineering firms/EPC contractors are currently establishing themselves on the market. These include TECPRO Systems and BHEL. TECPRO recently concluded a cooperation agreement with NTK. The established vendors of ORC systems in the cement industry include Ormat Technologies, Turboden (Pratt Whitney Power Systems) and ABB. Kalina systems are supplied by Siemens, Wasabi Energy (Global GeoThermal) and FLSmidth.

In addition to the Lengfurt WHR system of HeidelbergCement, Ormat Technologies references also include a 4 MW ORC system (Fig. 20) to Grasim Cement (formerly Ultratech; A.P. Cement) [13]. Turboden has more than 100 ORC systems on its reference list (status 2009), including a few in the cement industry, including one at Italcementi in Morocco (Fig. 21). ABB has been contracted by Holcim to supply a WHR system to the Untervaz cement plant (Switzerland). Using Kalina technology from Wasabi Energy, FLSmidth is going to install its first 8.6 MW system at the Khaipur cement plant of D.G. Khan in Pakistan. Considering the small number of ORC and Kalina systems in comparison to the overall market, it is at first glance somewhat astonishing that particularly western companies are choosing the ORC option. One of the reasons for this could be that especially in the established cement markets in Europe and America there are many smaller cement plants and that in these plants the ORC system is particularly advantageous.

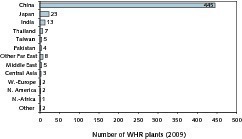

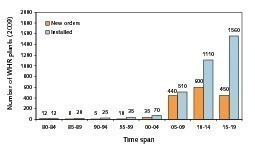

Figure 22 shows the estimated distribution of WHR systems by country up to 2009. 85 % of all systems are installed in China, 4 % in Japan and 3 % in India. All the Asian countries including the Middle East and Turkey have 99 % of the installed systems; the rest of the world with Europe, America and Africa have just 1 %. However, it is conceivable that this situation will change in the coming years. Figure 23 shows a forecast of the number of systems that will be installed in the cement industry up to 2019/20. It is expected that more than 1000 new orders will be awarded. There will be a peak in the period 2010-2014 due to the fact that in China a large proportion of the relevant plants and lines are already equipped with WHR technology, and the ratio of new plants will increase more slowly than in the past. The “new” markets are mainly to be found in India and other Asian countries, Africa, Europe and North and South America.

Widely differing information is received from vendors and operators regarding the cost-effectiveness of WHR systems. One reason for this is the fact that vendors in some cases assume excessively high efficiencies as a consequence of overestimated waste heat temperature levels and simultaneously fail to consider or underestimate the plant operating costs against the generated amount of electrical power in the capital reflux calculation. On the other hand, some system owners state that they have high operating and maintenance expenses that can exceed 10 % of the capital cost per year and thus severely worsen the capital reflux calculation. Ultimately, it is also a question of which method of capital reflux calculation is selected.

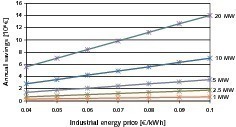

Possible annual savings related to 7,000 operating hours and depending on electricity prices and plant capacity are shown in Figure 24. With a reference price of 0.07 €/kWh, electricity cost savings of € 2.45 million are possible with a 5 MW system. At the reference price, a 10 MW system brings savings of 4.9 million €, while a 20 MW system brings savings of 9.8 million €. The system amortization thus depends on the specific costs per MW, the size of the system, the electricity price level and the annual operating and maintenance expenses of the system. On average, the capital cost for a conventional WHR system is 1.2 million €/MW. The specific costs of small systems are significantly higher, while those of larger systems are lower. ORC systems, which have so far been installed for the power range of up to 5.0 MW, have specific costs of at least 21 million €/ MW. The specific costs of Kalina systems are reported to be lower than those of ORC systems [14].

Of the 445 systems in China, 173 are designated as CDM projects (CDM = Clean Development Mechanism). Anhui Conch alone has implemented 21 projects. Within the framework of the JI (Joint Implementation) and CDM initiatives, it is possible under certain circumstances to trade CO2 certificates (CER = Certified Emission Reduction units) between industrialized countries (Annex I countries) and developing countries under the terms of the Kyoto Protocol. This is intended as a measure to promote favourably priced environmental protection projects in third countries. For instance, a cement producer in a developing country implements a WHR project. By generating electricity from otherwise unused waste heat and thus saving CO2 emissions, that cement producer earns a certain number of CERs and thus achieves extra income through the sale of these CERs. On the other hand, the purchaser of these CERs in the industrialized country (e.g. a power station in Europe) is given the right to produce the same amount of CO2 emissions.

CDM projects are therefore subjected to strict requirements that have to be checked by neutral auditors. One such requirement is that CDM projects have to be additional, i.e. projects that would not have been implemented without CDM incentives. Another requirement is that such projects must not be well-established practice in the developing country concerned. It is conspicuous from the market figures for WHR projects that in the period up to 2009 only 2 systems existed in Europe (1 in operation, 1 other planned) but almost 450 systems existed in China. From this point of view it could be reasoned that European countries are in fact the “developing countries” and it could also be asked why projects in China are not classified as “business-as-usual” in that country? Another discrepancy results from the cost effectiveness calculations for CDM projects. Figures for CDM projects reveal very poor cost effectiveness, although there are no fundamental project differences to otherwise financed WHR projects.

In many CDM projects exorbitantly high operating and maintenance expenses are applied, so that the annual overhead costs are sometimes up to 5 % of the capital cost. In integrated cement plants, the generation of power from waste heat would make it possible to reduce overall electrical power requirements and cut the capacity of transformers and switchplants. For this purpose, it would be necessary, for example, to take cement grinding systems out of service if on-site power generation with a WHR system is not possible. In China, for example, plant operators save the high power supply fees for starting up a kiln plant. Another way to make significant savings is to use air coolers or water circuits for the recooling, as already practised in many cement plants.

There are good medium-term and long-term prospects for WHR systems in the cement industry. Electricity is becoming more expensive, CO2-emission regulations are becoming more stringent and technologies for utilizing waste heat – also that from modern kiln plants – are becoming better and more reliable. Now that numerous cement plants in Asia and especially in China and Japan are already equipped with these systems, there is a strong potential for a similar development on the worldwide market. Recent orders, for example in Turkey, or for Holcim’s Untervaz cement plants, or for the South Bavarian Portland cement plant Gebr. Wiesböck & Co. in Rohrdorf, Germany, illustrate the fact that this technology is now becoming established in industrialized countries. The project in Rohrdorf is being implemented by a consortium of KHI and Siemens and will be the first conventional WHR system in a German cement plant. To provide further incentive to reduce CO2, governments should show initiative, for instance, by also offering investors tax advantages instead of just focusing on CDM models.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.