Investigations into the application of calcined clays as composite material in cement

This article describes the successful use of the muffle kiln and the entrained-flow calcinator for the manufacturing of pozzolanas from clay raw materials, some of which were of very impure nature. Firstly, this demonstrated the suitability of cheap materials for this process, and secondly it tested the manufacturing of calcined clays by a process that is suitable for industrial scale application in composite cements.

1 Introduction

The Portland cement manufacturing process results in a high emission of climate-damaging carbon dioxide, primarily due to the decomposition of limestone as the main component of the raw meal used for the burning of cement clinker [1]. One efficient way of reducing these emissions is substitution of the clinker content in the cement by more environmentally-friendly but nevertheless effective composite materials. Apart from largely inert limestone, the only materials globally available for this purpose are hard-coal fly ash, which reacts like pozzolana (approx. 700 million tpa...

1 Introduction

The Portland cement manufacturing process results in a high emission of climate-damaging carbon dioxide, primarily due to the decomposition of limestone as the main component of the raw meal used for the burning of cement clinker [1]. One efficient way of reducing these emissions is substitution of the clinker content in the cement by more environmentally-friendly but nevertheless effective composite materials. Apart from largely inert limestone, the only materials globally available for this purpose are hard-coal fly ash, which reacts like pozzolana (approx. 700 million tpa available worldwide) and granulated blast furnace slag, which has a latently hydraulic reaction (approx. 250 million tpa worldwide) [2]. Natural pozzolanas (30 million tpa) are only available regionally [3]. In view of the forecast increase in global cement sales, these quantities of reactive composite materials will not be enough to ensure a reduction of the amount of clinker in cement to a level of 60 to 70 % [3]. Moreover, granulated blast furnace slag and fly ash, as industrial side-products, are subject to strong economic and seasonal fluctuations which hinder their usage on a continuous basis [2].

In the future, it is possible that calcined clays could be an alternative to the named materials, as they are pozzolanically active like fly ash, and because clay – their raw material basis – is available in large quantities [4]. Positive experience has already been gained in the construction sector with calcined clays manufactured on the basis of kaolin. The produced metakaolins are highly reactive and of a quality that makes them an excellent candidate for use as a composite material in the cement industry [5]. However, due to the need for a multi-stage concentration process and also to the strong demand from the paper and ceramic industries, kaolin is a very expensive raw material. Against this background, the construction materials industry only uses metakaolin for special applications, such as the manufacturing of HPC/UHPC (as a substitute for silica fume) or as an additive for the improvement of chemical resistance of concrete. For an application in the large-scale manufacturing of cements, it is only possible to calcine clays which have a composition that makes them unsuitable for higher-value purposes, and which are correspondingly cheap.

The tests described here had the initial aim of establishing the extent to which non-kaolin clays with a low degree of purity and different mineralogy were suitable for the manufacturing of reactive pozzolanas. This initial, fundamental evaluation was conducted on a laboratory scale using a muffle kiln. The next step was to determine whether these calcined clays could also be manufactured on a larger scale. For this purpose, an entrained-flow calcinator was used. This type of system has proven itself on an industrial scale and enables continuous production with very short material retention times, which is why the process has also become known as flash calcination [6]. As this burning process differs fundamentally from the batch tests in the muffle kiln, the flash calciner testing was particularly aimed at determining the extent to which process-related changes occurred in the material properties of the calcined clays.

2 Materials and test procedure

The results achieved by other authors with very pure clays show an increasing potential reactivity of the most common clay minerals in the sequence illite, montmorillonite and kaolinite [7,8,9]. In order to be able to assess the entire effectiveness spectrum of calcined clays as pozzolanic components in cement, the materials selected for the described tests were a very impure illitic clay and a relatively pure kaolin. The chemical compositions were determined by means of x-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF). The mineralogy was determined by x-ray diffractometry (XRD) plus subsequent Rietveld refinement. The measurements were conducted on powders in Theta-2Theta configuration, using CuKα radiation. In addition, the specific surfaces of the two clays were measured using the BET and Blaine methods. The results of this characterization are shown in Table 1. Furthermore, the materials were subjected to thermal analysis (DSC/TGA) at a heating rate of 10 K/min.

The batch tests carried out on a laboratory scale were conducted in a muffle kiln with the material held in platinum crucibles. The heating rate was 10 K/min and the retention time was one hour. The material was subsequently removed from the kiln and cooled down in air. The pilot-scale burning tests were conducted in a flash calciner in the Technical Research Centre of ThyssenKrupp Industrial Solutions, with the material feed rate set to a continuous 40 kg/h. The retention time in the calciner loop was 0.6 to 0.9 seconds. Subsequent cooling of the material also took place in air.

In order to evaluate the success of the burning process, the amorphous phase content was determined by means of XRD/Rietveld, using ZnO as the internal standard. In addition, the specific surfaces were again determined. Morphological phenomena were clarified by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), using a Nova NanoSEM 230 from FEI. Phase analyses were also carried out using an energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometer (EDX). In the case of the calcined illitic clays (metaillite), the material was ground in a laboratory ball mill to 4000 cm2/g Blaine. This was not necessary in the case of the metakaolins because of their high degree of fineness.

To evaluate the reactivity, the compressive strength development was determined using mortar prisms in accordance with DIN EN 196-1. The basis for this evaluation was a commercially available CEM I 42.5 R cement with a sodium equivalent of 1.03 wt%. The effectiveness of the calcined clays was determined in composite cements with 70 wt% of this CEM I 42.5 R and 30 wt% of the respective burnt clay (CEM II/B-Q). As some of the cements had a very high water demand, as determined in accordance with DIN EN 196-3, a superplasticizer had to be added to the respective mortar mixtures in order to produce a consistency that could be compacted. A superplasticizer based on polycarboxylatether (PCE) was used for this purpose.

3 Test results

3.1 Laboratory tests in the muffle kiln

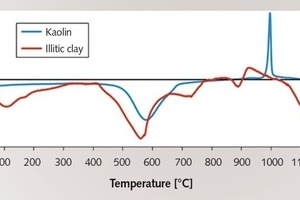

Figure 1 depicts the thermo-analytic curves of the kaolin and of the illitic clay for the temperature range up to 1200 °C. The kaolin shows the typical endothermic dehydroxylation of the clay minerals between 500 and 700 °C and a sharp exothermic recrystallization peak at 1000 °C. Similar reactions are also shown by the illitic clay, although the peak temperatures and the peak intensities differ considerably from those of kaolin. Moreover, the illitic clay shows further endothermic reactions, such as the dehydroxylation of muskovite at 700 °C, sintering phenomena at 900 °C and strong melt formation at temperatures above 1050 °C.

According to He et al. [7], the burning temperatures required in order to achieve optimum reactivity are 650 °C in the case of kaolinite and 930 °C in the case of illite. Correspondingly, and under observation of the thermo analysis results, the following temperature ranges were selected for the laboratory scale burning tests:

kaolin: 600, 700, 800 °C

illitic clay: 800, 900, 1000 °C.

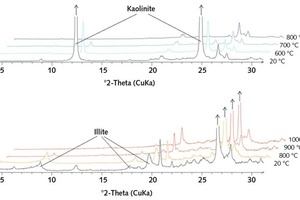

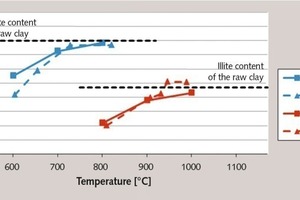

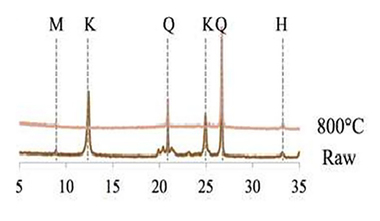

Figure 2 depicts the x-ray diffractograms of the accordingly burnt clays compared to the starting samples. The amorphous and therefore reactive contents are shown in Figure 3 (continuous lines). The diffractograms show that the conversion of the kaolinite in the x-ray amorphous phase takes place analogously to the dehydroxylation of the clay minerals. As this conversion is not yet concluded at 600 °C, a portion of the materials remains crystalline – which can be clearly seen from the kaolinite peak in the diffraction patterns. The partial retention of the kaolinite structure can therefore be attributed to the presence of residual water in the crystal structure. The clay minerals do not become completely amorphized until a temperature of 800°C is reached and all the hydroxide ions have been expelled. The x-ray amorphous product is referred to as metakaolin.

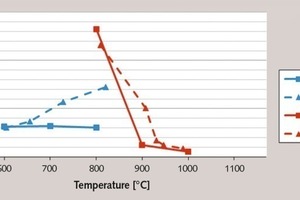

The illite differs in that even after the dehydroxylation (< 800 °C) it remains largely crystalline. Not until the commencement of sintering do the clay minerals slowly advance to complete amorphization. This relationship becomes clear on the basis of the BET surfaces of the individual burning products presented in Figure 4 (continuous line). These show a rapid decrease in values between 800 and 900 °C, which is clearly attributable to sintering and melting phenomena and the resultant closure of pore spaces. In the case of kaolin, this does not occur; the lack of vitrification means that there is no decrease in the BET surface. The high degree of disarrangement of the metakaolin is due exclusively to the loss of water of crystallization and not to a vitrification phase, a fact that has already been explained by other authors [8, 10].

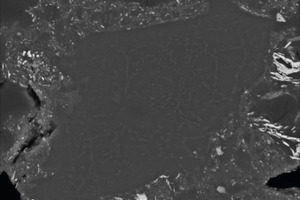

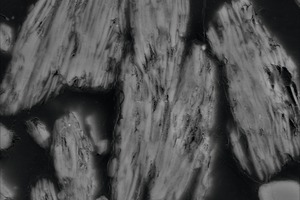

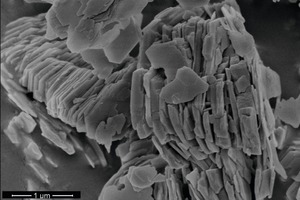

It can be derived from these considerations that the structures resulting from the conversion of the clay components into pozzolanically reactive metaphases are different in the case of illitic clays from those of kaolin. The calcination of illite, with the associated occurrence of a melt phase, produces a real glass with an extremely low porosity (Fig. 5). By contrast, the formation of metakaolin as a result of the dehydroxylation of kaolinite produces an x-ray amorphous phase but no vitreous phase. Also the corresponding metaphase of kaolin is characterized by a highly-porous structure (Fig. 7).

From a chemical point of view, the amorphized illite closely resembles the glass of a hard-coal fly ash (see Table 2), so that a comparable reactivity of the two materials in cementitious systems can be expected.

Due to the sintering of the particles during the vitrification of the illitic clay, its burnt products had to be ground prior to use in the cement. The set target grinding fineness was a Blaine value of 4000 cm2/g. This processing stage had only a minor influence on the BET surface.

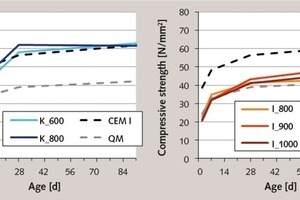

A consideration of the strength developments shown in Figure 6 reveals that the calcined clays make no contribution to the strength in the first 48 hours of cement hydration, and therefore hardly differ from an inert quartz meal. The materials only participate more strongly in the hardening in the course of the later reaction, with the various burnt products making greatly differing contributions to the strength development.

Thus, the values in cements containing metakaolin are significantly higher than the inert quartz meal reference after only seven days, and subsequently even exceed the strength values of pure Portland Cement. The higher amorphous phase content of the 800 °C-metakaolin has only a slight influence in this strength development.

By contrast, the burnt products of the illitic clay remain almost inert right up to the test date after seven days. Subsequently, they also contribute to the strength development, with the degree of contribution depending strongly on the burning temperature and thus initially on the quantity of formed vitreous phase. Until the sintering phase, tempered illites react pozzolanically, but only make a significant contribution to the strength development after the hydration periods > 28 days. The reaction kinetics of the metaillites thus closely resemble those of hard-coal fly ashes, which are also very slow in making a contribution to the strength development of the corresponding composite cements. The more weakly-burnt 800 °C-product differs in showing hardly any pozzolanic activity.

The reason for the slow conversion of the metaillites from the muffle kiln is the small internal surface produced by this method of calcination. This is also the explanation for the relatively low contribution of the 1000 °C-product to the strength development. Although this burnt product has a higher glass content than the 900 °C-metaillite, it has less than half the BET surface of that product. This shows that higher burning temperatures do not always improve the reactivity of the products, because the degree of reactivity depends not only on the glass content but also on the available reactive surface.

The high BET surface of metakaolins is advantageous for their pozzolanic reactivity. However, it has a negative effect on the workability of the produced concretes and mortars, raising the water demand of the cement after addition of 800 °C-metakaolin from 30.5 wt% to 46 wt%. As the respective mortar still allowed sufficient compaction, there was no need to add superplasticizer. The metaillites had no effect on the workability, but did cause red colouration of the mortar.

3.2 Pilot-scale tests in the flash calciner

The following section describes tests using a flash calciner to determine the extent to which the findings derived from the laboratory tests could be reproduced in pilot-scale tests. The amount of heat supplied to the calciner loop was set such that the mean temperatures measured over the material retention time complied with the previously defined testing range:

kaolin: 600, 660, 730, 820 °C

illitic clay: 810, 910, 930, 950, 990 °C.

As depicted in Figure 3, the flash calciner process resulted in practically the same degree of activation of the clay minerals as was the case with the muffle kiln process. The extremely short material retention times in the calciner seem to have almost no effect on the activation, which is attributable to the fine dispersal of the clays in the stream of gas. This is also confirmed by the only slightly delayed decline in the BET surface during the burning of the illitic clay (see Fig. 4).

By contrast, the behaviour of the kaolin during flash calcination is particularly striking. Differing from its reaction during the burning process in the muffle kiln, its specific surface increased in line with rising temperature. This effect is explained by Bridson et al. [12] as an expansion of the particles due to very rapid heating. In the case of so-called flash calcination, dehydroxylation of the clay minerals occurs faster than the liberated water can be diffused out of the particles. The consequence is an increase in steam pressure within the particles, which causes them to swell. Figure 7 clarifies the differences in morphology of metakaolins produced in a muffle kiln and a flash calciner. While the former displays a relatively dense layer structure, the latter has a considerably increased pore volume, which explains the enlarged internal surface.

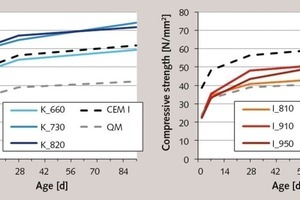

The modified particle morphology has a particularly strong effect on the capillary porosity of the metakaolin, and thus on its water absorption capacity. The drastic increase in these values as a consequence of flash calcination results in a further increase in the water demand of the respective composite cements compared to the products of muffle kiln processing. For example: to achieve standard stiffness, the cement with 730 °C-metakaolin demanded 58 wt% of water. As it is impossible to achieve a compactable consistency with such stiff cements, large superplasticizer quantities of 1.0 and 2.5 wt% respectively were required for the mortar tests with the 730 °C- and 820 °C-products of the burning process.

The results of the cement tests with the products from the flash calciner are presented in Figure 8. These results show sometimes considerable strength differences compared to the tests with muffle kiln products. All the composite cements produced using the flash-calcined clays had faster hardening times and higher final strengths than the cements produced using the muffle kiln products. This is attributable to the higher internal surfaces (see Fig. 4), which provided a larger and more quickly available quantity of material for the sequence of individual partial reactions of the hydration process. This is particularly conspicuous in the case of the metakaolins burnt at 730 and 820 °C. These make an early contribution to the cement strength, so that this is significantly higher than that of pure Portland cement after only seven days. The fact that the final strengths are also higher than those of cements produced using the muffle kiln kaolins shows that there is a higher degree of conversion during the pozzolanic reaction and is also a consequence of the larger BET surface. The somewhat lower strength values of the 660 °C-metakaolin can be explained by its smaller internal surface or by its lower amorphous phase content.

The effect of flash calcination on the hardening of the metaillite cements is somewhat less conspi-cuous, but still noticeable. It results in an acceleration of the hardening due to the larger internal surface after 28 days. While the muffle kiln products are still practically inert at this point in time, the 910 °C-metaillite from the flash calciner already makes a considerable contribution to the cement strength. With an almost identical amorphous phase content to that of the clays activated in the muffle kiln, this product has a very high BET-value of 10 m2/g (see Figs. 3 and 4). This means that more surface is available for the pozzolanic reaction, which increases the rate of conversion during the hydration process. In line with expectations, the BET-fineness decreases as the temperature rises, and the metaillite again becomes less active. However, the reaction potential of these products burnt at high temperatures is greater, which is shown by the 91-day strength, and is attributable to a further increase in the amorphous phase content.

In spite of their good contributions to the strength, none of the metaillites achieve the reactivity of a metakaolin, although the 910 °C-product from the flash calciner provides comparably large internal surfaces. This underlines the already determined differences between the two materials with regard to the nature of their amorphous phase, which in the case of calcined illite is a relatively stable alumosilicate glass resembling fly ash, but in the case of metakaolinite is x-ray amorphic but not glassy. The resultant fundamentally different structures are also the reason for the different working properties of the respective composite cements. Despite their higher BET-values, none of the metaillites caused an increase in the water demand of the cement. By contrast, the use of metakaolins resulted in an extremely stiff consistency of the green concrete, making it necessary to adapt the concrete formulation in order to achieve workability.

4 Conclusions

Using naturally occurring illitic clay, the described tests demonstrated that not only kaolins but also other, highly impure, clay raw materials with different clay minerals can be utilized for manufacturing reactive pozzolanas for composite cements. While the dehydroxylation of kaolin produces a reactive x-ray amorphous but non-vitreous metaphase – the metakaolin, the illite remains radiographically crystalline even after dehydration. Disintegration of the lattice structure due to sintering and melting phenomena does not occur until temperatures of 900 °C and more are reached. The active burnt product of the illite – the metaillite – can therefore be described as a real alumosilicate glass that closely resembles a hard-coal fly ash with regard to its composition and reactivity.

The pilot plant tests demonstrated that, despite the extremely short retention times, the continuous burning process in the flash calciner did not require higher temperatures than the batch tests in the muffle kiln in order to convert the different clays into their reactive metaphases. However, the rapid heating and the fine dispersal of the material in the reactor lead to larger internal surfaces, which increase the reactivity of the materials.

The usage of metakaolin always causes an increase in the water demand of the cement. As a consequence of the larger internal surface caused by flash calcination, the workability of the respective mortars and concretes deteriorates significantly. In construction practice, this means that higher water-to-cement ratios have to be applied, or larger quantities of superplasticizer have to be used, in order to achieve the specified target consistency. This down-side relativizes the positive evaluation of metakaolins with respect to their reactivity.

By contrast, the flash calcination of illitic clay results in burnt products that do not cause an increase in the water demand of the cement, although some have significantly larger BET-surfaces than the tempered materials from the muffle kiln. The significant contribution of the flash-calcined illitic clay products to the 28-day strength and the good workability of the produced cements make these metaillites an attractive composite material for practical construction purposes.

The conclusion drawn is that the flash calciner is a very suitable burning system for processing large quantities of clay raw materials that had previously been regarded as useless into a pozzolanically reactive product, and thus providing the industry with a low-CO2 composite material for cement manufacturing.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.