Cement kiln mercury control using the existing particulate control equipment

Mercury emissions are a problem factor in cement plants. In the worst case the plant has to be closed. The American Albemarle Corporation has developed a method to control the emission of mercury.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

U.S. cement manufacturers were originally faced with three control options. A fourth control option that has been developed exclusively for use in the cement industry will be described in this paper.

The first option is to shutdown. This is the least attractive option since both employment and capital assets are negatively impacted and merely make an economic downturn worse. The second option is to change the raw material and/or fuel input into the kiln. It is doubtful that the second option is possible since kilns are strongly wed to both raw materials and fuel supply.

The third option is to add one or more pieces of equipment after the process and before the stack gas is emitted. This equipment could include a baghouse, a scrubber and/or a regenerative thermal oxidizer (RTO). Each of these pieces of equipment would cost millions of dollars to build at a kiln and millions of dollars more to operate [2]. The Portland cement industry operates on narrow margins and is capital constrained. Thus, the necessity for this option could cause many more kilns to take the undesirable option one and shutdown.

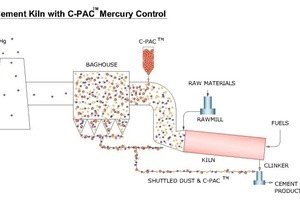

A fourth option has been developed which may be utilized in kilns that operate either an in-process particulate control device or an end-of-process particulate control device. The concept is simply to provide a sink for the mercury and to remove it from the system. The new method involves injecting a temperature-insensitive, concrete-friendly sorbent is into the PM control device at the time of highest mercury emissions. The sorbent is only injected long enough to capture enough mercury to meet the mercury MACT standard. The sorbent is collected with the cement kiln dust (CKD) and shuttled to the product mill. In order to do this, the sorbent also has to be concrete-friendly. The two phrases “temperature insensitive” and “concrete-friendly” will be fully defined in this document since a sorbent having both characteristics is required.

2 Temperature intensive sorbent

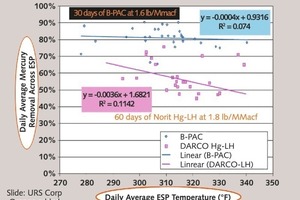

It has been discovered that gas-phase brominated sorbents have much better temperature stability for mercury capture than do either non-halogenated powdered activated carbon (PAC) sorbents or salt-impregnated bromide PAC sorbents. Bromine compounds are widely used as flame retardants and it is expected that the temperature insensitivity of gas-phase brominated PAC is partially due to the bromine reacted with the PAC. The temperature insensitivity of this gas-phase brominated PAC, and the resulting stable mercury removal, has been demonstrated in numerous full-scale field trials. The results from one such trial is presented in Figure 1.

This test was performed at a Midwestern power plant [3]. The target mercury removal rate was 80 %. This was achieved at an injection rate of 1.6 lb/MMacf in the case of the gas-phase brominated PAC (shown in blue in Figure 1). The removal rate was stable with temperature. On the other hand, the bromide salt-impregnated sorbent (shown in pink in Figure 1) did not achieve 80 % mercury removal even at the higher injection rate of 1.8 lb/MMacf and the removal rate declined rapidly with temperature. It should be noted that utility mercury emission rates are usually lower and less variable than those from cement kilns. For this reason, a different approach to control was needed for cement kilns.

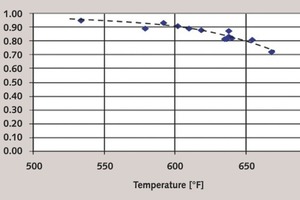

The mercury capacity of a gas-phase brominated sorbent is nearly invariant out to a temperature of about 550 °F, as demonstrated in Figure 2 [4].

3 Concrete-friendly sorbent

One main requirement of a concrete-friendly sorbent is that is should have minimal absorption of the air entrainment admixtures (AEA) that generate the air bubbles in concrete that provide the freeze/thaw capability of a concrete. Providing a sorbent that minimizes the capture of the AEA while capturing a high percentage of the mercury from the flue is not a simple feat, since the sorbent base is PAC.

A gas-phase brominated, concrete-friendly sorbent, C-PAC, has been widely tested in full-scale field trials in the utility industry and is now in commercial use. The results from the trial conducted at one plant are discussed below.

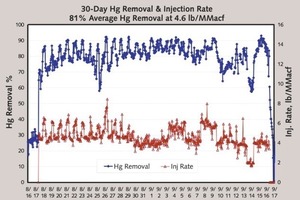

The trial was partially funded by the United States Department of Energy through the National Energy Technology Laboratory [5]. The purpose of the trial was to demonstrate high mercury removal rates with low levels of impact to the fly ash cementitious properties. The mercury removal results from the long-term 30‑day trial are presented in Figure 3.

In this trial, it was demonstrated that a mercury removal rate of over 80 % could be achieved with an injection rate of less than 5 lb/MMacf. Since the time of this trial, the properties of the gas-phase brominated PAC have been further improved and optimized to allow greater than 90 % mercury removal at injection rates as low as 1 lb/MMacf [6].

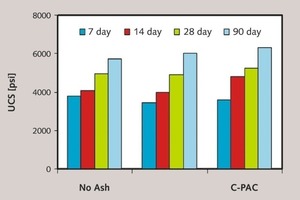

The mercury removal performance of the gas-phase brominated concrete-friendly PAC sorbent was demonstrated in these tests and several commercial applications. The question is what impact did the sorbent have on the cementitious properties of the material in which it is mixed, fly ash in this case. Several tests were used to evaluate the impact upon the fly ash cementitious properties. The compressive strength data for concrete samples made with no fly ash, baseline fly ash and fly ash containing the sorbent are presented in Figure 4.

The compressive strengths were measured at 3, 7, 28, 56, and 91 days. There was no significant difference in strength between the concretes that contained no ash, baseline fly ash or fly ash containing the sorbent [5]. These results have now been repeated in numerous tests and the gas-phase brominated concrete-friendly C-PAC is now in commercial use.

4 Albemarle control method

The M-PACT system is fed from a tanker or a silo, depending upon the customer desire. It contains a 1.5 MT storage hopper, a gravimetric feeder, eductor, and blower to feed the sorbent to a distribution system. The system is completely computer controlled and can feed up to 500 lb/hr of sorbent per feeder, with designs containing one or two feeders available. The Albemarle control method in use in a preheater/precalciner kiln is shown in Figure 6.

This mercury control method is based upon injecting into the in-process PM device used to capture CKD. The temperature insensitive, concrete-friendly sorbent is injected only when the mercury emission is highest. The sorbent is only injected long enough to capture enough mercury to get the facility below the emission standard. Because a concrete-friendly sorbent is used, the CKD captured during the period of sorbent injection can be shuttled to the cement product mill for inclusion in the final cement. Thus, a mercury sink is provided.

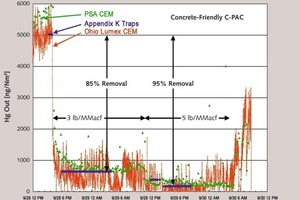

The authors are restricted by confidentiality agreements from disclosing any of the data from the five full-scale trials that we have conducted to date. However, we expect the performance to be something like that in a similar application shown in Figure 7 [7].

It can be seen that mercury removal rates over 90 % can be achieved. For most applications, injection during only the period of highest mercury removal will required, since the emissions during these periods are many times higher than other periods. For plants with very high mercury emissions, it may be necessary to inject all of the time and shuttle as much CKD as possible to the cement mill. Any CKD recycled to the kiln will either be reused for additional mercury capture or destroyed if it experiences a temperature above about 800 °C.

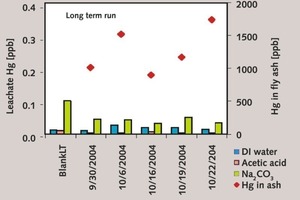

One concern is whether the mercury captured on the mercury sorbent (and included in the cement product) will leach mercury. Many studies have been performed on this subject and the short answer is no [8]. The leaching data for one of the Albemarle tests using a gas-phase brominated sorbent are shown in Figure 8 [5].

In Figure 6, the concentration of mercury in the ash is high but the concentration of mercury in the leachate is below that in the blank in most cases. The reason for this finding is that the sorbent continues to have mercury capacity and captures any mercury with which it comes in contact even in the blank solution.

As with fly ash, the mercury content of the CKD is greatly increased when the sorbent is utilized in the in-process method. The mercury is fixed on the sorbent and is not released when the CKD is shuttled to the final cement product. Thus, another exit for mercury from the cement kiln is created.

5 Conclusions

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.