Limestone powder CO2 scrubber – artificial limestone weathering for reduction of flue gas CO2 emissions

Slowing down climate change is one of the most important challenges of our age. Exceptional importance attaches in this context to reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, and those of carbon dioxide (CO2), in particular. Artificial limestone weathering opens up new perspectives in the reduction of CO2 emissions.

1 Introduction

Various technologies for the removal of CO₂ from the flue gas produced in combustion processes have been researched and tested in trial and pilot facilities in the past already. All of these “post-combustion” processes have in common the fact that they generally utilise...

Slowing down climate change is one of the most important challenges of our age. Exceptional importance attaches in this context to reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, and those of carbon dioxide (CO2), in particular. Artificial limestone weathering opens up new perspectives in the reduction of CO2 emissions.

1 Introduction

Various technologies for the removal of CO₂ from the flue gas produced in combustion processes have been researched and tested in trial and pilot facilities in the past already. All of these “post-combustion” processes have in common the fact that they generally utilise environmentally critical substances for removal, in some cases generate new emissions, and pursue, as part of the so-called “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) concept the problematical storage of the “captured” CO₂ in underground facilities. Also lacking is detailed knowledge of the feasibility and safety of storing CO₂ in geological formations across prolonged periods of time [1]. An Act on the testing of underground CO₂ storage was, it is true, approved by the German parliament in June 2012, but the federal states affected have already announced their intention of opposing such storage within their territories, with the consequence that the CCS concept must, in reality, be considered not to be capable of implementation in Germany.

The research project [2] examined here takes a totally different approach: a process which uses a limestone powder suspension to convert CO₂ to water-soluble hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate; so-called “carbonate hardness” or “carbonate scale”) has been developed. For this purpose, prescrubbed CO₂-containing flue gases, such as occur in flue gas desulphurisation, are submitted to wet scrubbing using a suspension of limestone powder. Calcium hydrogen carbonate (“calcium bicarbonate”), which also occurs as a natural constituent of limnic and oceanic waters, and thus fixes CO₂ in stable equilibrium, is formed, analogously to the natural weathering of limestone, rather than calcium sulphate.

The process is based on the reaction of CO₂ with calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) and water (H₂O) to form calcium hydrogen carbonate (Ca(HCO₃)2). Carbonic acid (H₂CO₃) formed by the dissolving of atmospheric CO₂ in rainwater or groundwater plays a part in limestone weathering. This acid, upon encountering rock containing calcium carbonate, reacts to form hydrogen carbonate ions (HCO₃-) and calcium ions (Ca2+). The products of weathering are transported via groundwater and surface water to the oceans, where they act as a buffer substance. In the long term, the concentrated calcium hydrogen carbonate solution yielded in this process is also to be discharged as a naturally occurring constituent substance of environmental waters into the aquifer and to contribute to buffering of limnic and ultimately of oceanic water. Use as a buffer for biological waste-water clean-up, and in other applications requiring high-buffer water, is also conceivable. Unlike CCS-concept processes as known up to now, the use of environmentally critical substances and the problematical storage of the captured CO₂ are thus eliminated.

The central focus of this project was on the determination of the technical and physico-chemical preconditions required for effective removal of carbon dioxide using the limestone-CO2 scrubbing process. The tests performed generated a substantiated data-base concerning attainable removal rates and reaction times, thus enables to conduct a process-engineering and economic evaluation of this procedure. The results obtained confirm the process’s suitability in principle for the removal of CO₂ from flue gases and for the stable transportation of the carbonate hardness formed in the aqueous fluid. The focus, in terms of potential users, is primarily on small and medium-sized emitters of flue gases.

2 Basic principles

A limestone-CO2 scrubbing process for the removal of sulphur dioxide has been successful routine practice in flue-gas clean-up in power-generating plants for decades: the flue gas (raw gas) is treated with a suspension consisting of limestone powder and water, causing sulphur dioxide to react to form low-solubility calcium sulphate:

SO₂ + CaCO₃ + 2 H₂O + 0.5 O₂ ‹—› CaSO₄ · 2 H₂O + CO₂

Equation 1 of flue gas desulphurisation (abbreviated version)

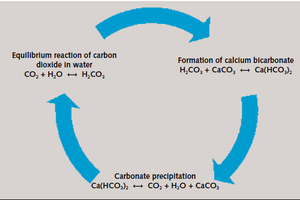

Limestone-CO2 scrubbing makes it possible to feed CO₂-containing flue gases to wet scrubbing using a limestone powder suspension. Concentrated calcium hydrogen carbonate solution (known from carbonate hardness) is produced, analogously to desulphurisation using calcium carbonate. The principle is based on the natural chemical weathering of carbonate rock, i.e., solution weathering (Figure 1). This is a component of the natural lime cycle, which consists of a continuous cyclical flow of carbon from the atmosphere, into the lithosphere and hydrosphere and back. When combined with rainwater or groundwater, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere forms carbonic acid, which converts the calcium carbonate contained in the rock to calcium hydrogen carbonate. The dissolved calcium hydrogen carbonate is carried by limnic waters into the sea, and acts as a natural buffer against ocean acidification. A certain portion of the calcium hydrogen carbonate can, in a reversal of the dissolution processes, be used again by means of chemical or biological processes for carbonate precipitation.

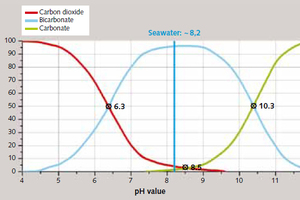

The chemical basis of these processes is provided by lime/carbonic acid equilibrium, which defines the pH-dependent equilibrium between the various carbon species of carbon dioxide (CO₂), hydrogen carbonate (HCO₃-) and carbonate (CO₃2-), and determines the lime-removing or lime-dissolving character of the water (Figure 2).

The pH of water in nature (sea, lake, river, groundwater) is determined by the amount of free carbonic acid contained in the water (dissolved CO₂ and H₂CO₃). pH levels of below 6.3 are dominated by CO₂, which is converted to hydrogen carbonate as pH rises, and is replaced as the dominant carbon compound by carbonate at pH 10.3 and above. This equilibrium determines the water’s buffer capacity which, in natural water systems, is in equilibrium with the surrounding environment [3]. The chemically basic action of the earth-alkali ion Ca2+ present in natural water controls dissolution and precipitation and assures a stable pH environment at around the neutral point (pH 6.3 to 8.3); surpluses of free carbonic acid are converted to Ca(HCO₃)₂ via limestone in the soil horizon.

3 Methods

The fundamental principles of this special process were firstly elaborated in terms of reaction kinetics, boundary conditions and the stability criteria for the concentrated calcium hydrogen carbonate solution on a laboratory scale. Samples of water of differing ion concentration were mixed in an experimental system with limestone powder, chalk and/or precipitate and the rate of and total conversion of the dissolution reaction of the products upon addition of CO₂ measured.

The boundary parameters determined then formed the basis for pilot-scale testing. Synthetic flue gases were used in these experiments. Verification of the data obtained in the laboratory on CO₂ removal rates and on rate of (HCO₃-) formation for the pilot plant was performed under a range of different boundary conditions.

After successful determination of the general suitability of this new scrubbing process and of the necessary process parameters, using synthetic flue gases, the results were evaluated in practical tests using the real flue gas from a combined heat+power (CHP) plant unit installed at a sewage-treatment plant for generation of electricity from digester gas and incorporating waste-heat recovery and utilisation.

Finally, a process-engineering evaluation to permit assessment of the limestone-CO2 scrubbing process against the CCS concept was performed on the basis of the test results.

The principle of commercial-scale use of limestone weathering as a CO₂ scrubbing process has been cost-calculated assuming as a theoretical basis US conditions and for the volumes of water required inter alia by Ken Caldeira et al., geo-engineering expert and lead IPCC author. The authors conclude from their investigations that the process is in theory suitable for use in power-generating plants located close to the coast and already using seawater for cooling purposes, but also emphasise that practical tests remain necessary before a conclusive evaluation can be stated [4, 5].

4 Laboratory tests

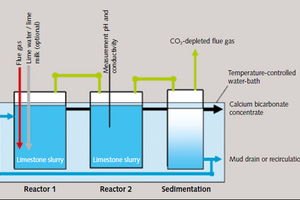

The laboratory apparatus consists of two reactors, with separate piping systems which permit continuous and systematic feed of the suspended lime products and commercially available gases into the two reactors (Figure 3). Optional additives can be metered in and/or the sediment returned from the connected sedimentation stage to the dissolution reactors via feed pipes in the cover. The apparatus is installed in a conditionable water bath.

The scrubbing suspension was in each case put into the reactors prior to the tests and kept in suspension by means of vane-type agitators. Continuous measurement of pH and conductivity during the course of each test provided information on the progress of the dissolution reaction and the rate of calcium hydrogen carbonate formation. Final total alkalinity (AT 4.3) was measured in the supernatant water of the scrubbing suspension after the attainment of lime/carbonic acid equilibrium. CO₂-removal efficiency was then calculated using the final parameters of conductivity, pH, temperature and AT 4.3.

The selection of lime products as sources of calcium carbonate for these tests was intended to cover the entire bandwidth of the sample parameters expected to be relevant for this process. Two samples of limestone powder (named as 'GK 059' and 'GK 091'), a sample of chalk and a commercial precipitate (as a chemically pure control substance) were used for the tests.

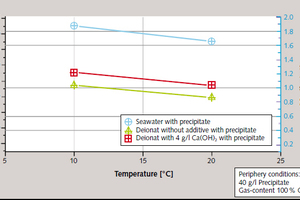

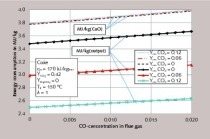

The decrease in solubility in the lime/carbonic acid system as temperature rises is a known phenomenon for which it was necessary, for the planned test system, to determine the exact amounts under the respective given boundary conditions. The influence of temperature was determined for the 10 to 20 °C range on p.a. precipitate in suspensions with differing ion contents. It was 0.02 g/l per °C. It became apparent here that removal efficiency is influenced significantly more by the type of scrubbing fluid than by its temperature (Figure 4).

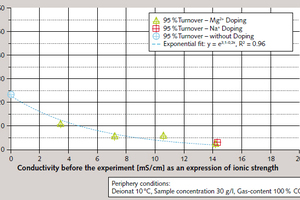

Further tests were performed using samples of water doped with NaCl and/or MgCl₂ ∙ 6 H₂O, since it was suspected that the pronounced influence of seawater on separation efficiency might be the result of this water’s high magnesium ion concentration. These tests indicated that simple dependence on ion concentration exists, irrespective of ion species. Ion concentration also had a positive influence on the rate of CO₂ conversion to (HCO₃-) , with an exponential dependence on initial conductivity, as an expression of ion concentration (Figure 5).

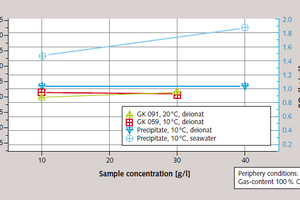

In the case of suspensions using deionised water, the effects of specimen concentration proved to be extremely slight. Limitation is probably the result of the solubility equilibrium of the suspension, which is significantly exceeded at the concentrations used. A significant boost in separation efficiency by up to 27 % can be achieved at 10 °C by increasing specimen concentration when seawater rather than deionised water is used (Figure 6).

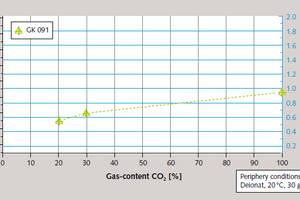

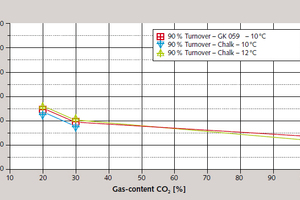

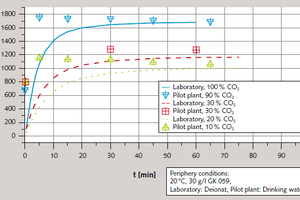

The CO₂ content of the flue gas is a parameter of particular importance for this process, with correlations, via increased CO₂ partial pressure, both with removal efficiency and rate of reaction. Removal efficiency was practically doubled (Figure 7) and conversion reaction time more than halved (Figure 8) when the CO₂ content of the flue gas was increased from 20 % to 100 % total content.

The possibility of recycling the lime material used was investigated for determination of the necessary amount of carbonate-containing substance, since the specimens were at all times used in surplus, and were never totally dissolved. The relevant tests were performed twice using the limestone powder residue of the preceding test in each case, with no addition of new test material. These repeat tests achieved a virtually identical scrubbing result and it was also demonstrated, on the basis of the plot of conductivity, that there was no significant decrease in reaction rate and that unconsumed material can thus be returned to the reaction with no losses in efficiency.

The stability of the scrubbing solutions is determined by the lime/acid equilibrium established in the solution. Particular importance attaches in this context to the factors of temperature, CO₂ partial pressure above the solution and pH. Alterations to these parameters can result in precipitation of CaCO₃, which generally takes place across longer periods of time. CaCO₃ has a tendency to supersaturation in aquatic systems. All the scrubbing solutions used here took the form of Ca(HCO₃)₂ saturated systems, which thus had an extremely high carbonate hardness. Dilutions will thus always occur in the vicinity of water-discharge points, by reason of which precipitation of CaCO₃ need not be anticipated at discharge into water systems. Corresponding storage tests confirmed this assumption. After completion of testing, the scrubbing solution was stored for a number of days and total alkalinity measured prior to and after storage. Only slight decreases of less than 0.05 g/l in CO₂ concentration were ascertained across the period of storage.

5 Commercial-scale implementation

of the process: pilot plant

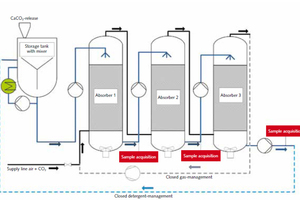

A mobile absorption/desorption system available at the Institute of Energy and Environmental Technology (IUTA) was modified for the practically orientated tests (Figure 9). The system was operated via three absorption units installed in series. The limestone powder and any additives utilised were put into a feed vessel and brought to suspension by means of an integrated agitator. The lime suspension generated was fed in counterflow to the flue gas to be cleaned in the individual absorber stages. The reaction vessels were also additionally equipped with agitation systems in order to keep the limestone powder in suspension throughout the process. The scrubbing fluid was distributed by means of baffle plates fitted below the outlet apertures in the nozzle array. The absorbers featured plastic packing to increase the contact surface area and residence time. It was possible to operate the test system with an open or a closed gas/scrubbing-fluid circuit, depending on the particular task.

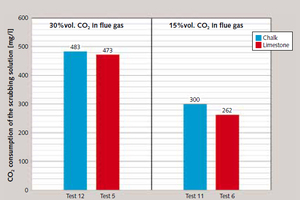

The pilot tests were performed at room temperature and using 30 g/l of the respective additive. A high-quality limestone powder and chalk from the selection of specimens from the preceding laboratory experiments were used as the additive. The suitability of these two products was indicated by the preliminary laboratory-scale tests. The concentration of CO₂ in the synthetic flue gas was varied from 15 to 90 %vol. CO₂ in the individual tests, with gas flow remaining constant at 30 m3/h.

Initial orientational tests were performed with a closed gas and scrubbing-fluid circuit in order to verify the repeatability of the laboratory-scale tests in the pilot plant. The conductivities achieved in the laboratory tests were also confirmed (Figure 10). The optimised gas-scrubbing conditions in the pilot facility, resulting from the installation of packing to enlarge contact surfaces, for example, promoted a tendency toward higher reaction rates.

Samples of the scrubbing fluid were taken after passage through all of the three absorber vessels in order to determine its maximum CO₂ absorption capacity and the removal efficiency of each respective absorber stage. Figure 11 shows the scrubbing fluid’s CO₂ absorption in the final absorber. On this basis, up to 483 mg CO₂ are absorbed per litre of scrubbing solution in scrubbing of synthetic flue gases containing 30 %vol. CO₂, and up to 300 mg per litre of scrubbing solution in processing of flue gases with a CO₂ content of 15 %vol. (Figure 11).

The concluding pilot-scale tests with an open gas and scrubbing-fluid circuit served the purpose of direct preparation for the practical tests, and were performed under conditions analogous to those for the latter tests.

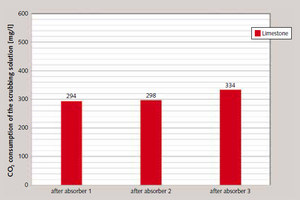

Figure 12 shows by way of example the results of analysis of the three samples taken simultaneously downstream of the three absorption scrubbers after a 20 min. period of operation using the limestone powder at a 15 %vol. concentration of CO₂. The greatest amount of CO₂ is absorbed by the scrubbing fluid in the first absorber, while only relatively slight further cleaning of the flue gas occurs in the downstream scrubbing units.

6 Practical tests

The practical tests were conducted at the municipal sewage-treatment plant in Bad Orb/Germany. The primary and surplus sludge yielded is anaerobically and mesophilically digested. Energy-route utilisation of the digester gas in a combined heat+power (CHP) plant unit follows, after temporary storage in a gas holder. The flue gas generated in combustion of the digester gas is released to the atmosphere via a horizontal flue gas pipe with an inner diameter of 110 mm. Flue gas temperature in design-load operation was 130° C, and the flow velocity of the gas (10.5 m/s) was monitored by means of a vane anemometer. An operating volumetric flue gas flow of approx. 360 Om3/h can be calculated from this. Average CO₂ concentration in the flue gas was 12 %vol.. The CHP plant unit operates for around 4300 h each year, resulting in annual CO₂ emissions of some 40 000 kg.

The experimental scrubber system was connected to the flue gas pipe by means of a heat-resistant plastic hose (inner diameter: 115 mm). Volumetric flue gas flow through the experimental scrubber was reduced to ≤ 70 m3/h, corresponding to the design of this system. The flow of flue gas for cleaning was thus at the upper extreme of the experimental scrubber’s performance range, but it was possible to at least partially compensate for this by increasing the volumetric flow of scrubbing fluid, which reached 1400 l/h and around 3500 l/h in the individual tests. After passing through the series-installed absorber stages, the CO₂-reduced flue gas was released to the atmosphere.

Only the test apparatus with an open gas and scrubbing-fluid circuit was used in the practical tests. CO₂ concentration during these tests remained very largely constant, at around 11.8 %vol., with only slight fluctuations of some ± 0.2 %vol..

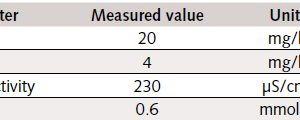

The same products as used in the pilot-scale tests were used here as calcium-carbonate-containing additives, at concentrations of 3 %wt. and 1.5 %wt., respectively. A series of tests involving the addition of approx. 3.5 %wt of sodium chloride (99 % NaCl) served the purpose of evaluation of the use of seawater. Two water supplies were available at the Bad Orb sewage-treatment plant, the municipal mains water supply being selected for use after preliminary tests, thanks to its constant chemical composition. The relevant analytical data are shown in Table 1:

As in the pilot-scale tests, the suspension was firstly prepared in the receiver vessel and the scrubbing-fluid pumps and agitators in the three absorption vessels then started. The gas hose was connected to the flue gas socket and the flue gas fed into the test scrubber as soon as a stable flow of scru

The gas analysers, which displayed and recorded the CO₂ content in the flue gas (upstream of the inlet to the experimental scrubber) and in the cleaned gas (downstream of the outlet from the experimental scrubber) made it possible to track the plot of CO₂ concentration. Samples of scrubbing fluid were taken shortly after the CO₂ concentration at the outlet from the experimental scrubber had reached a constant value. The volumetric flow of scrubbing fluid was set to the higher value in each case after the initial sampling of this fluid, after which the CO₂ concentration displayed on the gas analyser at the gas outlet from the system (cleaned-gas side) fell. The second scrubbing-fluid sample was taken as soon as a stable value was again achieved here, and the experiment then continued until the suspension prepared in the receiver vessel had been used up.

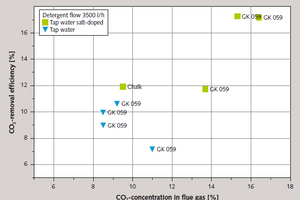

The highest cleaning rates within ecologically and economically rational boundary conditions were achieved in the practical tests using salt-doped mains water. Figure 13 shows the correlation between removal efficiency and CO₂ concentration in the flue gas at a high volumetric scrubbing-fluid flow and with the use of salt water.

CO₂ removal efficiency from flue gases using a limestone scrubber is dependent primarily on the ion concentration and volumetric flow of the scrubbing fluid. The two scrubbing additives tested achieved comparable degrees of gas clean-up. The question of whether the additive was used in the test for the first time or a residual quantity from a previous test used as the basis for preparation of the suspension also proved not to be of any significance. In contrast to the laboratory experiments, a diminution of CO₂ comparable to that achieved with higher suspension concentrations was attained even with a significantly lower quantity of lime (1.5 %wt.), probably as a result of the large contact surface between the flue gas and the scrubbing fluid provided in the test scrubber, and of better mixing of the suspension. It proved possible to remove up to 11.2 % of the CO₂ content of the flue gas, depending on the test parameters selected, when using salt-free suspensions. The removal rate was up to 17.2 % when synthetic seawater was used.

7 Process-engineering evaluation

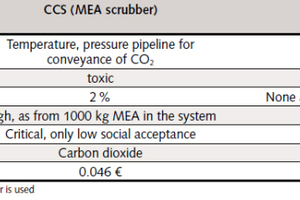

The test results obtained will now be used for a comparative assessment of the limestone-CO2 scrubbing process against the previously discussed and at least partially tested concept based on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. The declared aim of CCS technology is that of capturing carbon dioxide directly at its (punctiform) source and of storing it permanently in deep geological formations.

Limestone-CO2 scrubbing, a technological simulation of the natural process of weathering of carbonate rock, uses no environmentally dubious substances. In principle, only (sea) water, limestone powder and drive energy for the pumps are necessary for scrubbing using this process.

The simple and relatively low-energy process configuration should also be added to the benefits possessed by limestone-CO2 scrubbing over the CCS processes in terms of the environmental impact of the substances in the scrubbing fluid. Unlike the CCS processes, in which the carbon dioxide absorbed by the scrubbing fluid in the absorber is stripped out again, with the input in the desorber of large quantities of thermal energy, the CO₂ remains in the scrubbing fluid after limestone-CO2 scrubbing and can then, for example, be discharged back into the sea. The energy otherwise required for underground compression of the CO₂ is also saved. In addition, the tests performed demonstrated that CO₂ absorption in limestone-CO2 scrubbing is indeed promoted by a surplus of limestone powder, but also that the unconsumed lime can be used again in the scrubbing process with no loss of efficiency. Approximate cost benefit estimates indicated that this fact, in combination with the energy advantages of the process, result in relatively low operating costs.

Direct comparison of the CO₂ removal efficiencies of the two processes favours the amine-based (MEA) scrubbers used for the CCS processes. Up to around 800 mg CO₂ were absorbed per litre of scrubbing fluid in the practical tests performed using the limestone scrubber. At approx. 44 g/l scrubbing solution (differential loading 0.2 mol/mol), the CO₂ absorption achieved using a 30 % solution of monoethanolamine (MEA) is greater by almost two orders of magnitude, depending on the specific process selected. The disadvantage of the significantly lower solubility of carbon dioxide in the limestone scrubber can to some extent be balanced out by means of corresponding process configuration and operation. In a cascade configuration, in which a number of scrubbing stages, each treating the flue gas received from the previous stage with fresh scrubbing solution, are installed one after the other, CO₂ removal efficiency can be raised from stage to stage. This arrangement also increases scrubbing-fluid consumption and investment costs, however.

It can be ascertained, by way of summary, that the CO₂ limestone scrubber examined here possesses on ecological and process-engineering criteria significant advantages over the CCS processes discussed (Table 2).

Perspectives

In addition to the further technological development of the process, with the aim of optimising CO₂ removal rates in the commercial-scale process, future research projects will also need to demonstrate the acceptability of discharging the calcium hydrogen carbonate solution into natural water systems, and to verify the anticipated positive ecological effects. Not only water-chemistry and biological analyses, but also the modelling, with the participation of a marine research institution, of the potential effects in both limnic and marine environments, should be performed for this purpose. Particular attention must also be devoted to the stability of the calcium hydrogen carbonate solution after its dilution with a range of different surface waters.

The further technological development of the limestone-CO2 scrubber must firstly concentrate on process arrangement and operation. Here, the research results have already outlined options for optimisation of removal efficiency. The plant technology used for these tests consisted of a universally deployable absorption system, which was modified only to conform with the special requirements of this process. The special reaction kinetics requires a specially adapted process featuring a cascade-configuration scrubber installation. Removal rates of around 80 % of the CO₂ contained in the flue gas are targeted using this technology in a planned follow-up project.

8 Acknowledgements

IGF Project AiF 16548 N, conducted by the German Lime and Mortar Research Foundation and the Institute of Energy and Environmental Technology (IUTA) received financial support via the AiF German Federation of Industrial Research Associations in the context of the Programme for Promotion of Joint Industrial Research (IGF) of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy) on the basis of a resolution adopted by the parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany.

References

[1] Federal German Environmental Bureau: CCS - Rahmenbedingungen des Umweltschutzes für eine sich entwickelnde Technik. (2009) Dessau: http://www.umweltdaten.de/publikationen/fpdf-l/3804.pdf

[2] Haas, S.; Berry, A.; Erich, E. & Weber, N.: Rückführung von anthropogenem CO2 in den natürlichen Kohlenstoffkreislauf mittels Kalkprodukten, Research reports by the German Lime and Mortar Research Foundation (2013), No. 1, 122 p.

[3] Hütter, L. A.: Wasser und Wasseruntersuchung (1992), Salle + Sauerländer, Frankfurt/Main

[4] Caldeira, K. & Rau, G. H. (2000): Accelerating carbonate dissolution to sequester carbon dioxide in the ocean: Geochemical implications. Geophysical Research Letters 27(2): 225-228

[5] Rau, G. H., Knauss, K. G.; Langer, W. H. & Caldeira, K.: Reducing energy-related CO2 emissions using accelerated weathering of limestone, Energy 32 (2007), pp. 1471-1477

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.