Towards a low-carbon post OPC era – external framing conditions

To avoid major damage caused by climate change, great efforts are needed to mitigate further greenhouse gas emissions or even remove those gases from the atmosphere. For the cement industry this means that as long as no sophisticated solutions exist as alternative to universal OPC in the mid-term, negative emissions technologies (NETs) become more and more important.

1 Introduction

The way we use resources fundamentally affects the state of the environment and economy, and the well-being of humanity. The global metabolism is extremely material-intensive. With the quantity of the materials used their influence on the environment increases. The impact ranges from the extraction of the basic materials to the waste arising. Emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases and other hazardous pollutants are to be taken into account. The construction industry is one of the largest economic and most material-intensive sectors. The annual global construction volume...

1 Introduction

The way we use resources fundamentally affects the state of the environment and economy, and the well-being of humanity. The global metabolism is extremely material-intensive. With the quantity of the materials used their influence on the environment increases. The impact ranges from the extraction of the basic materials to the waste arising. Emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases and other hazardous pollutants are to be taken into account. The construction industry is one of the largest economic and most material-intensive sectors. The annual global construction volume is currently estimated at US$ 9000 billion [1] with more than 40 Gt material throughput. By the year 2025, an increase to US$ 15000 billion is expected. After the international financial and economic crisis in 2008, there has been a shift in construction activities from industrialized countries to emerging economies, especially China and India.

There are strong arguments that the construction sector is facing serious challenges to meet future requirements for achieving the Paris Agreement [2], the implementation of issues of the New Urban Agenda [3] as well as targets of sustainable development in the context of resource use [4]. Decarbonization of the building sector plays a key role in achieving the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal. Figure 1 shows the rising CO2-emissions in the building sector in the time frame 1990 to 2012 [5], caused by the increasing indirect emissions1.

Since the core of modern buildings and infrastructures is basically made of concrete, the cement industry delivering the hydraulic mineral binder for concrete is also strongly affected. 28 billion t of concrete are produced per year, one ton of concrete on average contains about 150 kg of cement. The climate-relevant step in cement production is the burning of the clinker. About one third of the raw materials for clinker manufacturing consist of chemically bound CO2, which is released during burning. Other high CO2 emissions result from the fuels used. On a global average, one ton of clinker corresponds to 0.85 t CO2 [6]. Due to this fact, the cement industry is strongly involved in decarbonization activities within the construction sector [7]. However, companies must more than double their efforts to reduce emissions if they are to limit global warming to below two degrees, as agreed in the Paris climate deal.

There is broad agreement that the possibilities to significantly lower the CO2-emissions of production of conventional cement are limited. Traditional measures such as more efficient combustion technologies, rising shares of traditional clinker substitutes and more efficient process technologies are not even sufficient to meet the aspired targets.

The working group “Cementitious Binders” of the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS) has been systematically investigating issues of innovation and alternative binder concepts within cement industry for more than 10 years now [8, 9, 10]. In a previous article in this journal the authors described, how internal factors act as structural barriers and delay the implementation of alternatives [11, 12]. It was shown that within the matured cement innovation system innovations are systemic incremental with long innovation cycles and the transformation of more radical solutions is in the mid-term extremely risky. Therefore, many insiders prefer the further development of cement with cement clinker as the core material.

In this paper, we present an investigation which is focused on the question of how external functions affect core strategies of the cement industry currently and in future. Regarding the CO2-issue, climate relevant key functions e.g. climate change objectives, self-commitments, specific carbon regulation mechanisms such as the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme are defined by national and international climate policy.

The urgency for a radical change has recently been highlighted by a special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [13]. There is no longer room for delays in achieving the targets. In this context, a change can be noticed towards carbon-neutrality or even carbon-negative strategies. The implications of this shift are discussed in more detail within this paper. This is to a distinct degree in line with the IEA technology roadmap in which carbon capture and storage (CCS) plays a decisive role within the mitigation strategies of the global cement industry [14].

The paper is organized as follows. To illustrate the CO2-issue which is a major societal challenge, the study starts describing the more and more visible changes in the environment due to climate change, and the evidence that climate change is caused by anthropogenic activities and that the natural sinks for CO2 are overloaded. The next topic deals with the political and external framing conditions and objectives of climate protection on the basis of “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) [15]. There are indications that the objectives will not be met, and additional measures such as CCS and negative emission technologies (NETs) will come into play in the future. These are presented in a separate chapter. The next chapters embed the global and European cement industry in these framework conditions and show how dependent this sector seems to be on these new measures to achieve more ambitious climate targets. Possible consequences for the cement industry are discussed when remaining within the clinker paradigm. Taking part in carbon-negative transformations seems a logical consequence in the future. The implications of this scenario are discussed in detail with a focus on CCS. Finally, the authors give some conclusions and recommendations from their view.

2 The CO2-issue from the global perspective

The assessment reports of the IPCC, based on a multitude of scientific studies and the bulletins of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), inter alia, impressively demonstrate that the climate conditions are changing on a global scale (Figure 2) [16, 17]. The global temperature is rising with increasing concentrations of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The global mean temperature was in 2017 in the order of 1 °C above pre-industrial levels.

As a consequence, the global sea level has been steadily increasing since 1900 at a rate of at least 1 to 2.5 mm per year due to expansion of the warming seawater and melting of glaciers and ice sheets over land [18]. Between 1966 and 2010, the amount of land and sea ice that is snow-covered each year has decreased over many Northern Hemisphere regions, especially during the spring snow melt season [19]. This is a serious issue, because seasonal snow is an important part of Earth’s climate regulation system. Snow cover helps regulate the temperature of the Earth’s surface, and once that snow melts, the water helps to fill rivers and reservoirs in many regions of the world. As a side effect, the impacts of coastal erosion and sea flooding in densely populated and infrastructure-rich coastal urban areas become a more and more important issue of climate change impact. Currently the sea level rises by 0.3 cm per year [20]. A further consequence of climate change is the increasing impact of heat waves, droughts on the one side, and heavy precipitation events on the other.

There are distinct indications, that climate change is man-made. Important indicators are the CO2 and greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Currently, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is higher than ever before in the past 800000 years. Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry have now been growing for decades with pauses only during global economic downturns. For the first time, emissions stalled from 2014 to 2016 while the global economy continued to expand. Preliminary data show, that CO2-emissions related to fossil fuels and industry grew again by 1.4 % in 2017, reaching a historic high of 36.6 Gt. [22]. CO2 accumulated in the atmosphere at unprecedented rates close to 3 parts per million (ppm) per year in 2015 and 2016, despite stable fossil fuel emissions [17]. As shown in Figure 3 the natural CO2-balance of absorption and release is disturbed. Sinks such as the ocean and the terrestrial biosphere are not able to compensate for the increase in CO2-emissions with the effect that the amount of CO2 is increasing in the atmosphere.

If the further development of CO2 emissions remains unlimited, experts expect a significant increase in catastrophic weather events and the long-term detoriation of the environment, which will have a strong impact on living conditions on earth. In this context, the Special Report SR1.5 of IPCC strongly points out the potential impact of a further 1.5 or 2.0 °C rise until the end of the century on environment [13].

3 External framing conditions and key

functions regarding the CO2-issue

Agreements for the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), such as the Kyoto Protocol, had so far only obliged rich industrialized countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. The Paris Agreement 2015 has committed the entire community of states to taking action to keep the global temperature rise well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels this century, and to make further efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 °C [24].

A central component of the Paris agreement are the “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) which describe the intended contributions of each of the parties to reach, in the end, the goal of reducing the net greenhouse gas emissions to zero after 2050 and what they plan to do for adaptation to climate change [24]. The NDCs can contain economy-wide targets but also detailed descriptions of policies and measures to reach sector-specific targets, to participate in carbon trading or to promote carbon capture technologies.

In the context of external key functions, carbon trading, especially the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), has been created for guiding decisions of carbon intensive industries like the cement industry by carbon price. It is a cornerstone of the EU’s policy operationalization to combat climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively. However, structural issues and lobbying of policymakers have undermined the potential for change for the sectors. As for the cement industry, an important argument was among others to minimize carbon leakage [25]. Until recently, the steering effect was only weak because of the very low price of carbon and free allowances given to the carbon intensive sectors. In Figure 4 it can be seen how the cement industry was able to cumulate a notable surplus of allowances over the last years. Between the years 2012-2017, the carbon prize was in the range of 5-7 €/t of CO2. Carbon prices need to rise by three to six times to provide incentives to deploy new technologies such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

In the last year, however, there has been some movement in this area. Carbon price increased and peaked in September 2018 up to 24 €/t CO2 (Figure 5).

Despite the progression of some ups and downs, a trend toward a steady increase cannot be overlooked. According to a recent published report by Carbon Tracker, the prices for European CO2 emission certificates could settle at an average of 35 to 40 €/t for the years 2019-2023. [26]. The fact that carbon prices increased so rapidly is due to the planned EU-wide reduction of emission certificates in 2019-2023. According to commodity experts some of the currently observed fluctuations are due to the recent buying behavior which suggested a high level of speculative activity. If these forecasts are confirmed and the trend remains valid, this will also increase the pressure to realize necessary mitigation actions.

There are other global initiatives to introduce carbon pricing, with different national carbon prices advocated, which take into account the state of development and different approaches to climate policy in the respective countries. According to a World Bank report [27], about a fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions are now carbon priced; 25 % of these as a tax, 75 % within an emission trading system. In the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of 81 countries under the Paris Agreement, carbon pricing is envisaged as an important component in the reduction (mitigation) of greenhouse gas emissions. Chapter 6 of the Paris Convention and the corresponding passages of the Paris Rulebook regulate the development of global carbon market mechanisms through which national initiatives can be linked.

In the context of intended carbon net-zero or carbon-negative transformations of industry and society, a possible simple action would be to expand the EU ETS by assigning a new certificate of CO2 removal to producers of fossil carbon, mandating a progressively increasing proportion of CO2 to be captured, used or stored [29].

Another important external key function which cannot be neglected is concerned with the roadmap “New Urban Agenda” which will affect the global construction industry in future [3]. Cities are currently responsible for about 70 % of energy consumption and 80 % of greenhouse gases – and that with land use of only two percent of the icefree terrestrial land. Therefore, climate change has emerged as a central issue in this agenda. It is one of central outcomes of the UN conference “Habitat III” on housing and sustainable urban development, which was set up in October 2016 in Quito, that action in urban centres is critical to global climate change adaptation and decarbonization (i.e. net zero CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions) [3]. Habitat III should be an opportunity to give these dynamics further momentum in the face of mounting pressure from climate change. A shift to new technologies is needed to sufficiently cut planet-warming emissions.

4 Options of advanced measures

towards decarbonization

There are indications, that the average global temperature increase at some point within this century will exceed the 1.5° C mark. This means that much of the CO2 emitted in the first half of the century needs to be removed from the atmosphere again in the second half in order to achieve this target. As already shown in Figure 3, the amount of CO2 within the atmosphere is increasing as a result of the disturbed net-balance of CO2-emission and absorption. What matters, is to strengthen the “other side” of the CO2-balance. The analysis of Rogelj et al. [30] shows for example that there are no feasible 1.5 °C scenarios without negative emissions. Negative emissions mean that in a net balance more CO2 is removed from the atmosphere than emitted. This is in agreement with results currently presented by the Special Report SR1.5 of the IPCC which strongly points out the potential impact of a 1.5 or 2.0 °C rise on the environment [13]. The panel demands drastic carbon negative activities. IPCC scenarios associated with a more than even chance of achieving the 2 °C target are characterized by capture rates of 10 Gt CO2 per year in 2050, 25 Gt CO2 per year in 2100 and cumulative storage of 800-3000 Gt CO2 by the end of the century. This would mean that carbon-negative transformations must be achieved in all industrial sectors. Since the operationalization of such transformations become more and more important within the political discourse, the intended technologies (NETs) are briefly illustrated.

Among the negative emissions technologies (NETs), Carbon Capture technologies play the most important role. This also includes those technologies committed by COP21 by combining the use of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) or options like direct air capture (DAC), and carbon capture and utilization (CCU) [15, 29, 31]. Since CCS plays an outstanding role within intended decarbonization strategies of the cement industry, this technology will be discussed in detail in a separate section.

Approaches for capturing greenhouse gases at the moment of their formation by CCS, expand the possibilities for the further use of fossil fuels in specific sectors. This can be added to by measures which have been summarized under the term “carbon dioxide removal (CDR)” [31]. This can involve the strengthening of natural sinks, from the protection of forests and coastal areas (“BlueCarbon”) to “Climate Engineering”, e.g. through ocean fertilization by CO2. However, the isolated consideration of biological land-based sinks in particular makes little sense due to the increasing use of biomass as a regenerative energy source. Relevant studies concerned with the possibilities or impossibilities of achieving the 2° or 1.5° target, have already internal offsetted the absorption of CO2 during plant growth for energy production within the framework of the concept of negative emissions. The emissions are negative if biomass is used for energy production and the resulting CO2-emissions are absorbed by CCS (BECCS). The crux is that correct balancing is not trivial in this context, as shown by the large number of relevant publications [32, 33]. BECCS is currently operating with five plants worldwide on an industrial scale. The technical maturity and costs of BECCS are comparable to conventional Fossil-CCS-technologies. Costs of the latter will be discussed in more detail in the section focused on issues regarding the cement industry. But the large-scale realization of BECCS depends on first having access to a mature CCS industry.

A final example in the context of CO2-removal is the direct absorption of CO2 (DAC) from the atmosphere (“artificial trees” up to artificial weathering) [31]. DAC can be used to offset greenhouse gas emissions (e.g. from transport) that may occur elsewhere, or to compensate for an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere due to inadequate mitigation measures in the past. The technical realization is likely to be dominated by the requirement to process vast volumes of air in order to absorb a meaningful volume of CO2, with the capture of 1 Mt CO2/a necessitating the processing of 80000 m3/s of air! The direct capture of CO2 from the air is possible, but technically and economically challenging. Currently, the cost of DAC is likely to be in the range of $600-1000 per t CO2.

To recover the costs of CO2-capture by creating a sale price, utilization of CO2 (CCU) is discussed as a method of commercially valuing CO2. The intention is clear, instead of paying for the capturing and storing of CO2, the gas can be used to produce products with high added value. Beside using CO2 for enhancing oil recovery about 114 Mt CO2 were 2012 globally used for utilization of CO2 – such as chemical reagents in water treatment or urea making [31].

After this rather general discussion of the framework conditions with regard to the CO2-issue and the consequences for operationalization, the following sections will deal with specific framing conditions of the cement industry and discuss the resulting implications.

5 CO2-emissions of the global cement industry –

a closer look

The current global demand for concrete today leads to extremely high cement consumption with corresponding CO2-emissions. To determine the contribution of cement production to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, the authors analyze the total CO2-emissions of the global cement industry. In the literature the available data sets can differ significantly and the values depend on what they refer to (only process-emissions or taking into account energy related emissions). The range extends from 6 to 10 % [34, 35, 36, 37]. In order to make plausible, how these amounts are composed, in-house estimations are carried out based on elaborate investigations, the authors provided 2011 for similar calculations, which took into account the structure of the global cement industry [38]. Using the same assessment basis the database was updated with regard to 2014, mainly based on in-house plausibility calculations and checked by specific data published in the literature, presentations and from organizations2. The year 2014 was selected as reference since corresponding data was presented within the IEA&CSI roadmap 2018 [14]. The amounts assessed refer to absolute values, not taking into account any conventions for ignoring biogenic emissions or allocations to external balances. The results are presented in Table 1.

According to this balance we assess that the total absolute CO2-emissions of the global cement industry are 2.72 Gt in 2014 of which 1.49 Gt CO2 can be attributed to process-emissions and 0.94 Gt CO2 resulting from thermal demand. The latter quantity is rather rarely reported in publications. It contains also emissions based on biomass which are formally declared as zero emissions. With regard to the reference year, the considered biomass contributes only < 2 %. Under the global perspective this share can nearly be neglected. We relate these results to data published by Global Carbon Project (GCP), PBL Netherlands Environment Assessment Agency (PBL), and Andrews [34, 35, 36].

Figure 6 shows two kinds of CO2-emissions: the sum of emissions resulting from the total global use of fossil fuels and the process-emissions of the global cement industry (left axis) and purely the process emissions (right axis), both within the period 1990 to 2015.

The data show that for 2014 these process-emissions are on the same level as those assessed by ITAS (1.49 Gt CO2). A significant higher value is shown by GCP which may assume a higher clinker production. According to these sources the total CO2-emissions from the total global use of fossil fuels and cement process-emissions were in the mean 36 Gt in 2014. According to our calculations the global cement industry contributed 7.5 % to the total CO2-emissions in 2014, taking into account process and thermal emissions.

6 Decarbonization strategies

of the cement industry

In recent years, the cement industry has made great efforts to minimize the CO2-emissions within the cement production process. Unfortunately, the potentials of measures for lowering CO2-emissions within the conventional cement production are already largely exhausted. It is crucial that no real radical solutions are available in the medium term to reduce CO2-emissions during production. Recently, the development of radical innovations seems rather disappointing due to the fact that these developments have fallen far short of self-imposed goals and public expectations. This is to a certain extent due to systemic factors of the innovation system cement [12]. Due to extraordinary long R&D periods which characterize this innovation system, new approaches based on little experience are extremely risky. An important issue is that company disclosure on R&D spending and product development is currently inadequate to assess the extent to which cement companies are allocating their capital to the benefit of a low-carbon transition.

Especially in Europe specific economic framing conditions in the last decade had not further forced the internal innovation pressure toward more emission savings – above all the intensified development of radical low carbon innovations. Until the year 2007 the cement process-emissions in the EU increased compared to those of 1990 in contrast to the total GHG-emissions of the EU which were on track to the reduction goals of the Kyoto Protocol (Figure 7). After the economic downturn beginning in the year 2007 the emissions especially of Spain and Italy decreased dramatically [39].

In the year 2015 the cement CO2 process-emissions of the whole EU were about 25 % below the value of 1990, which is comparable to or even more than the reduction of the total GHG-emissions of the EU. Due to the economic downturn after 2008, the cement industry in the EU more than met the Kyoto target. It also becomes clear why the cement sector has been able to accumulate such a large surplus of CO2 certificates. But meanwhile the economic upswing leads to an increase in emissions.

The lacking perspective towards alternatives has strengthened those experts who are skeptical about the feasibility of any innovation beyond the OPC paradigm and trust only this cement system for solving the CO2-issue. A prominent strategy within the roadmap is now to lower the clinker-to-cement-ratio (c/c-ratio) far below 0.7 by the increased use of ternary mixtures of feasible inert, pozzolanic and latent-hydraulic clinker substitute materials (or: Supplementary Cementing Materials, SCM). But the question arises whether a further reduction of the global c/c-ratio to 0.5 by 2050, as targeted by IEA and CSI, will be realistic even if new cements using calcined clay as constituent will be implemented to a relevant extent [11].

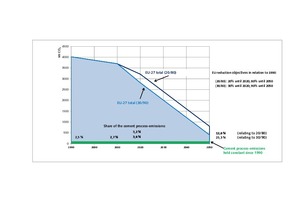

From the authors’ point of view, this strategy falls short. Firstly, there are uncertainties regarding issues like durability, realization conditions, and delivery security of high-quality SCM for new SCM-based cements with low c/c-ratio. The extents to which these systems will lead to drastic CO2-savings, is currently not sufficiently elaborated. Possibly they are insufficient in the context of drastic CO2-reductions. Secondly, insisting on unavoidable emissions and exemptions in the regulations could prove too short-sighted strategically. If there are no radical mitigation strategies, there will be a rising share of process-emissions in the total greenhouse gas emissions which are expected to decline in the future. This is schematically depicted in Figure 8 for process-emissions of the European cement industries in relation to reduction goals of the EU until 2050.

To illustrate the consequences, a kind of worst case scenario in which the process-emissions are held constant, i.e. not taking into account any significant advances in reducing the CO2-emission level through a reduction in demand for clinker, but also without an increase of the cement production in Europe. In this case a prescribed value of 2.5 % for the share of process-emissions in 1990 will rise to 3.6 % in 2020 and 25 % in 2050 while the total emissions are reduced by 30 % or 90 %, respectively, in relation to the year 1990. This may enhance the pressure on the cement industry in the long-term.

7 CCS as an option for the cement industry –

a closer look

In the context of meeting the climate change commitments of limiting warming to less than 2 °C, most integrated assessment models (IAMs) cannot find a solution without CCS. Participation in decarbonization transformations is a prerequisite for the global cement industry. Of course this is valid for many other industrial sectors too. But there seems currently no alternative to CCS to radically reduce the CO2-emissions that are inherent to the manufacturing process. In this section, CCS is analyzed from a holistic perspective of TA. This means that important implications and issues regarding chance, potentials and risks to remove and store CO2 are discussed.

7.1 Carbon capture (CC)

From the technological perspective, a number of different CC-technologies are applicable to the clinker production. There are several variants of post-combustion technologies, e.g. solvent scrubbing or the use of solid sorbents, calcium looping, oxy-fuel and direct capture [40]. For a detailed technical discussion of each of these options, see [29, 41, 42]. From the perspective of TA, there seems no serious technological barrier, even if many questions needed to be analyzed and clarified. Technology readiness levels (TRLs) for different CC-technologies applied to the cement industry range between 4-6, depending on the variants considered [40]. The key issue for CC in the context of cement is to ensure that the quality of clinker remains the same when CC has been applied [28].

CC-Technologies are energy intensive. Capturing CO2 via amine scrubbing has been observed to be three times more energy intensive than oxy-firing. As stated in the ECRA-reports which reflect the view of European cement industry oxyfuel technology might have a high potential to be applied to existing kilns [43, 44]. The results presented are mainly based on model calculations performed by the Research Institute of the Cement Industry in Düsseldorf. Calcium looping is another important technology.

The costs of CO2-capture on cement plants have been assessed, but never as comprehensively as such costs on power generation. Amine scrubbing is likely to be more expensive than oxy-firing the kiln and calcium looping with costs for the former ranging between $65 and $165 per ton of CO2 [45]. Costs for calcium looping vary between $20 to $75, those for oxy-fuel are about $60. Costs also depend on region. Barker et al. noted, that plants in a far-eastern location would be significantly cheaper (more than 50 % cheaper) than those in a European location [31]. Linking several facilities, e.g. to use recovered waste heat from neighbouring facilities, has been identified to be a key for cost reduction. The integration of a cement plant at a nearby power plant would significantly reduce the costs for post-combustion capture.

Due to progress in gaining technological knowledge, there is currently a drive to proof the principle within industrial processes. Norcem (in collaboration with its parent company, HeidelbergCement, and ECRA) has led the way in terms of testing several variants on real flue gases. Regarding oxy-fuel combustion, ECRA has currently announced to develop a 500-1000 t/d pilot plant to be operational by 2019, with costs between € 40 and 60 million. The key extra cost component was stated to be the oxygen supply. Calcium looping will also be tested [31]. The LEILAC project, headed by Calix Europe is aiming to demonstrate the direct capture process. For this approach and other newer developments see Harder [42]. But all in all, as the Carbon Disclosure Project stresses: otherwise progress is limited [37].

A key-issue will be whether it will be possible to build up a CCS-infrastructure step by step that will network more and more multiple CO2-sources with each other to take advantage of economies of scale and to optimize the further transition pathway. But this is challenging. Interlinking CO2-capture facilities of cement plants with those of power plants may not be as easy as planned. Each source has its own specific requirements. What is challenging is that there are impurities in absorbed CO2 and there is a need for a more or less complex and costly transport infrastructure. The level and type of potential impurities can differ between different power plant and industrial sources and also between the capture technologies installed at the source [46].

7.2 Storage – where to put the CO2?

The CCS research questions – particular within the cement community are mainly focused on technological issues regarding the capturing of CO2. Whilst the technical issues of this step become more and more clear, other important issues of CCS have been less well addressed so far. The implications and the impact on society and environment is as yet not so clear. Aspects of public acceptance and the need of public participation in decisions with regard to the fate of captured CO2 have been so far inadequately taken into account [31].

The following options are discussed for the fate of captured CO2. Of course, this topic not only affects the cement industry, other carbon-intensive sectors are just as obliged to deal with this problem. In principle, ocean storage and geological storage are considered to be the main fields for CO2 sequestration. Although it was one of, the solutions originally thought of ocean storage is still in an early phase of development and it has the negative reputation of geoengineering. In the field of geological storage, four main types of formations are currently under consideration [29]:

depleted oil (and gas) reservoirs [46, 47]

unmineable coal beds [31]

saline aquifers [46, 48]

mineral storage [31]

Injecting CO2 into oil reservoirs has been commercially used for several decades in the petroleum sector [47]. The primary aim was enhancing oil recovery (EOR). The application of an EOR technique can increase the cumulative recovery by an additional 5-15 %. A portion of this CO2 is trapped in the reservoir through capillary forces. The main share of CO2 exists either in the form of free phase CO2 or is dissolved within the mobile oil and could be recovered. Approximately 95 % of all CO2-EOR activity takes place in the U.S.. Approximately 60 Mt of CO2 (corresponds to 4 % of total annual U.S. oil production) is injected annually into U.S. oil fields.

Due to the increasing pressure to combat climate change, greater attention is being paid to the potential for CO2-EOR to support geological CO2-storage for climate change mitigation. This option offers commercial opportunities: two business activities are combined, namely oil recovery and CO2-storage for profit [46]. So it not surprising, that 13 of the 17 operating commercial-scale CCS projects are already in the context of EOR. The knowledge and experience of many decades leads to the fact that CO2-EOR is assigned to TRL 9. In contrast, CO2-storage by enhanced gas recovery (EGR) and storage in depleted oil and gas fields have not reached operation at commercial-scale, thus, both are still at the demonstration phase (TRL 7) [46].

The widespread success of CO2-EOR in the U.S. could potentially be extended to other regions in the world where it is technically and economically feasible. There is growing interest in CO2-EOR in the Middle East and China. It has also been advocated for the North Sea, but economic conditions, particularly for offshore locations have, to date, not been favourable. As stated by IEA, the main factors that currently inhibit investment in offshore CO2-EOR are the upfront investment costs, loss of oil production during work-overs and lack of significant CO2 volumes. Costs of CO2 need to drop to ~2 €/t, if the oil price is as high as $50/bbl [46]. Although the current economic situation does not favour CCS, there is political support for offshore CO2-storage in some countries bordering the North Sea.

The use of unmineable coal beds, eventually recovering methane by Enhanced Coal Bed Methane (ECBM) can be an option but it will make the coal used for CO2-storage irreversibly unavailable even if future sustainable technologies allow the use of coal.

There are growing interests in CO2-storage in saline aquifers, due to their enormous potential storage capacity and several commercial scale projects are in development both onshore and offshore including Sleipner CO2 Storage, Snøhvit CO2 Storage and Quest in the North Sea [29, 46] Saline aquifers can be sandstones or limestones, but to be a potential storage reservoir for CO2 they must have specific properties of porosity and permeability. Usually only aquifers below 800 m below sea level are considered, where CO2 exists in its dense phase as a liquid. In addition an overlying cap rock that is impermeable to the passage of CO2 is required. Injected CO2 remains in the reservoir rock by a combination of three main processes, fixation in traps/pores, dissolution in the saline waters, and formation of minerals in the pore spaces [48].

Mineral storage is envisaged as injection of CO2 directly into the subsurface in suitable rock types to precipitate a mineral by forming carbonates. Technologically, this is an approach of artificial weathering of predominantly magnesium silicate-containing rocks, under discussion since 1990 [8] and on which huge expectations rest in connection with climate engineering. Extensive research and development work on this approach was done in particular in the National Energy Technology Laboratory, Albany and the Los Alamos National Laboratory [8]. This principle was also used by Novacem which tried to produce magnesium (hydro-) carbonates as cementitious binder but this invention has as yet failed [12]. Their potential for CO2-storage is assessed to be very high [8]. But this approach is still in a relatively early phase of development. This process has never yet been tested at a commercial scale. A number of uncertainties ranging from the need of an extremely detailed knowledge of the stratigraphic structure of the basalts to full understanding of the chemical reactions still limit their use.

7.3 Carbon usage?

The captured CO2 can be stored underground (CCS) or used as a chemical precursor of products. Since the effort regarding storage of CO2 is clearly immense, some experts try to find ways towards alternatives to the usage of CO2. In this context, the use of CO2 as a C1- synthetic building block is forced. It is not surprising that CO2 is not widely used as a chemical precursor, due to the low energy state of CO2. CO2 has a free standard formation enthalpy of -393 kJ/mol. The activation (reduction) of CO2 as a reversal of combustion is correspondingly energy-intensive. The approach requires innovation chains that also include upstream and downstream steps. This includes e.g. the intelligent synthesis of high-energy reaction partners for CO2. The main focus is on access to products with high added value, such as polymers and specialty chemicals. In this context, power-to-gas activities should be mentioned, where for example CO2-capture and methanization are concerned [49]. However, the economic realization conditions are likely to be unfavorable. The quantity potential for the material use of CO2 in chemical syntheses is limited. For products of the chemical industry, such as polymers and other basic chemical products, the global substitution potential against the background of the total emitted CO2-amounts is estimated by the chemical industry itself to be less than 1 % per year [50]. Further, the life cycle is sometimes hard to assess – as each actor along the chain can gain a benefit in their narrow view, yet the overall global emissions for the climate see no benefit, and are often worse than with no CCUS [15]. In the context of climate protection the question arises whether these efforts are worthwhile at all. But taking into account the need to enhance resource efficiency such research efforts may become more important.

8 Discussion and assessment

As shown in the previous sections, climate targets have to be strengthened to meet climate change commitments to limit warming. This is challenging by the fact, that the additional future impact on CO2-budget by the growth of world population in the next decades needs be compensated, too. Advanced measures and Negative Technologies (NETs) become more and more important. Haszeldine et al. come to the conclusion: “No NETs means no 2°C target” [15].

Against this background all building constructions would have to be carbon neutral or negative by 2030 to meet the targets [51]. To achieve this, the construction industry would either have to use materials (e. g. concrete, steel and bricks) which are produced emission-free by CCS or by another technological means or substitute these materials with carbon-free or carbon-negative natural materials such as stone or wood. There exists a discussion that the service life of concrete and mortars could lead to negative emissions in the long term, as concrete absorbs to some extent CO2 from the air over time. But this effect is possibly overestimated, as will be discussed by the authors in a special article. Further, carbon negative transformation within the clinker paradigm is only possible if the energy supply for cement production is switched to emission-free sources and the carbon dioxide produced during cement production is captured and permanently stored [52]. For the global cement industry, taking part in carbon-negative transformations seems a prerequisite to survive in the future. Against this background, it is a logical consequence, that CCS plays a decisive role within the mitigation strategies in the IEA technology roadmap.

In the context of advanced decarbonization measures, the options NETs, CCS and carbon-free and carbon-negative cementitious materials must be assessed with regard to potentials, chances and risks. At this point technology assessment can come into play as one option of assessment method. Very important issues are the realization conditions, risk management, and societal aspects.

Stakeholders may agree that CCS only makes sense if it significantly relieves the global climate. It must be recognized, that the quantities (Gt of CO2) that need to be captured and stored for making an effective contribution to climate protection are immense. A transition in this direction would present an unprecedented technical and economic challenge globally [53, 54]. Due to the fact that CCS is very energy-intensive, its implementation will cause considerable costs. In a new report the potential of NETs to meet the Paris Agreement’s targets is evaluated to be relatively low. According this assessment NETs have “limited realistic potential” to halt increases in the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at the scale envisioned in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios. None of the NETs has the potential to deliver carbon removals at the gigaton (Gt) scale [55].

Assessing knowledge, uncertainties and risk is challenging in this field [56]. Experts agree that CCS seems technologically basically feasible, but the main key question is, where to put this huge amount of CO2? There exist different perceptions of the risk of geological storage. Several camps of stakeholder can be identified, which, similar to the assessment issues concerning nuclear waste disposal, face each other and represent very different perceptions and positions. The key is to guarantee secure retention of CO2 in geological formations over thousands of years. There are experts with a high degree of trust in technics in general and they consider the current knowledge base for CCS far advanced. Risk in storage would be in the near future at a responsible level. Other experts, particularly from social science and holistic environmental research are more skeptical with regard to controllability and uncertainties of risk in this field. In this context, there is a different perception regarding “enough” knowledge for risk assessment. As can be demonstrated for the case of EOR, supporters point out that there is widespread experience in the petroleum, mining and geothermal industries of working with critical issues like faults and fractures in geological formations and provide there is sufficient characterization of their properties. All agree that there are detailed research questions which still have to be clarified. Elaborate time intensive work is required to understand better the processes and quantify the heterogeneity of low permeability fault rock, to test the effectiveness of the current methods and analysis. It is difficult to estimate the time needed to do this. The crux is that experts often generate their knowledge and expertise by using a numerical model to predict potential impacts which is good tool for EIAs, but models need to be verified [29].

Results are in general difficult to communicate to the public. Societal aspects such as public participation, governance, and acceptance have hardly been taken into account in previous evaluations. There is a risk that acceptance of different storage options may be perceived differently in public, by politics, by stakeholders and NGO, even if the scientific basis concerning risk is the same. As mentioned, EOR has been in use in the USA for decades. With EOR and EGR, there is a danger that specific economic and societal interests will be mixed up, which could change perception. In this context, it should also be pointed out that for fracking-technologies similar considerations exist with regard to the increased interest of using CO2 in this field. Despite economic benefits, this would be more than questionable from the view of environmental protection.

Implementing CCS would mean to implement storage locations in mature regions. In the context of the cement industry, cement plants usually have a sales radius of 100-150 km and are therefore located near urbanized regions. This affinity to urbanized regions will increase significantly in the coming decades. Local groups or ethnic groups are socio-psychological heterogenic and will have different priorities, different issues, different perceptions and therefore will be hard to convince [57]. Although the risks could be low for experts they might be perceived by non-experts as high. Public reaction to new technology can be irrational. Some stakeholders are wary of technical experts. This situation is getting worse, because in many countries the socio-psychological perception is changing to scientifically substantiated facts, as was recently pointed out by ETH-Zürich [58]. The trend can be observed that both politicians and the public are increasingly hostile to scientific findings if this information clashes with their own view. Facts are now not only ignored but negated. As a consequence, in the authors’ view it cannot be excluded that, especially in mature regions, a low level of acceptance and possibly resistance will build up and that there will be long delays in the approval procedures. This conceals an incalculable risk for the cement industry. If no other solution emerges, the cement industry is at the mercy of the CCS-technology. From the current perspective the realization conditions of CCS are unclear and there are serious indications, that the transition could be more difficult and much more delayed than expected [29, 52].

In this context, the cement industry finds itself in a tricky situation. In the medium term, there is no alternative binder in sight that can substitute OPC with low-carbon or even carbon-negative properties. Innovation conditions for the development of radical solutions are unfavourable [11]. Due to systemic framing conditions within the innovation system cement, progress in innovation can traditionally, only be expected incrementally. Currently, 10-15 years are the common horizon for an incremental approval. The expected time horizons for development of more radical solutions pose extremely high risks to get an invention into the market. The successful transition of more radical approaches requires completely different framework conditions. Company disclosure on R&D spending and product development is currently inadequate to assess the extent to which cement companies are allocating their capital to benefit from a low-carbon transition [12]. This issue cannot be overestimated. Currently patent portfolios of small companies and institutions most outside the cement community play an important role in attracting investment and interest from major cement producers [59]. For example, LafargeHolcim is partnering with a US firm, Solidia Technologies, on development of the latter’s carbon-cured low-clinker concrete. A significant innovation boost in technology is required to reduce carbon emissions within the cement sector and the willingness to make large investments and build up appropriate research structures.

9 Conclusions and recommendations

In the authors’ view an important key-strategy of decarbonization within the cement sector will be beyond CCS by investing in longer-term solutions not end-of-the-chain but where emissions occur: the forced development of superb low-carbon cement products. But a successful transition of more radical approaches requires completely different framework conditions. There has to be a total rethink and change. As the authors assume, serious alternatives to OPC may be available in 10-20 years at the earliest due to the assumption, that an improved knowledge base in cement chemistry can be expected in this time frame.

This recommendation is conform with the environmentalist view and is probably best summarized by a 2006 position paper by the Climate Action Network Europe umbrella group, which argued that CCS ‘may have a role to play’ but ‘climate policy cannot wait for any one technology’ [60].

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 Total building sector CO2-emissions [5]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_de7b95ca6e654aed43e6083c410f736c/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_1-7753cf3a8076af50.jpeg)

![2 Change of global surface temperature [21]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_5f5c9261fd8f9c30ab6eb5beadd4db1d/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_2-64e27442d1029f4f.jpeg)

![3 The historical global carbon budget 1900-2017 [23]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_79e6156c76a0aa80bfaa901098785185/w300_h200_x187_y125_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_3-487266fa19c0e75d.jpeg)

![4 Free allowances related to cement from clinker production [25]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_c7f62eab18802ade5e66a6d57b6e2893/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_4_links-310471a31e3725d4.jpeg)

![5 Development of the CO2 European allowances price between 2015 and spring 2019 [28]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_9f6571b838883d0194183249eb23d2f7/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_5-b1c9e49698ed5284.jpeg)

![6 Development of global CO2-emissions by using fossil fuels plus cement process-emissions (left axis) and cement process (right axis) in the period 1990 to 2015. Sources: Global Carbon Project (GCP), PBL Netherlands Environment Assessment Agency (PBL), Andrews [32, 33, 34, 35]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_7a3ee0c5845e74d013d4e4fcf114ef60/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_6-790916769e58a794.jpeg)

![7 Development of process-emissions within the EU from 1990 to 2015 [39]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/8/1/5/0/5/tok_3c6998d469a58b5bc09acd51179ca651/w300_h200_x421_y297_Process_Achternbosch_CO2_Figure_7-35281c74d1fd3a03.jpeg)