Process-relevant characterisation of the flow properties of surface treated cement

Improving the flowability of cement helps to reduce the risk of poor process performance, a critical issue for an industry targeting the very highest levels of efficiency. This article describes the use of dynamic flow testing to characterise the flow properties of Portland cements and to quantify the enhancement achieved by surface treatment.

1 Introduction

The scale, capital-intensity and environmental impact of the cement industry shape its requirements for exceptional reliability and enhanced sustainability. With modern kiln systems capable of throughputs as high as 15000 t of clinker per day and investment costs for a new cement line in the region of several hundred million euros [1] the efficiency of cement manufacturing lines is critical. Rigorous process optimisation, along with the highest levels of reliability, maximises return on investment. At this scale even minimal amounts of unplanned downtime can rapidly add-up to...

1 Introduction

The scale, capital-intensity and environmental impact of the cement industry shape its requirements for exceptional reliability and enhanced sustainability. With modern kiln systems capable of throughputs as high as 15000 t of clinker per day and investment costs for a new cement line in the region of several hundred million euros [1] the efficiency of cement manufacturing lines is critical. Rigorous process optimisation, along with the highest levels of reliability, maximises return on investment. At this scale even minimal amounts of unplanned downtime can rapidly add-up to significant amounts of lost revenue and the consistent, reliable flow of both raw and finished materials is essential.

However, cement manufacturing processes are changing as the industry pursues an aggressive sustainability agenda, implementing a range of strategies to reduce the environmental footprint, most especially with respect to CO2 emissions. The majority of CO2 released – around 2/3 – comes from the limestone decomposition reactions associated with clinker production. The reduction of clinker to cement ratios through the increased use of blended cements is therefore an important CO2 mitigation strategy [2]. For example, in India, a country making excellent progress towards sustainability targets, blended cement increased from 68 % to 73 % of total cement production from 2010 to 2017, contributing to an overall reduction in CO2 intensity of 49 kg CO2/t cement (to 670 kgCO2/tcement) over the same period [3]. Blended cements typically contain alternative materials such as granulated blast furnace slag and fly ash, waste products that are easily sourced from different suppliers but that can vary markedly in terms of their properties.

Better process and product understanding underpin efforts to implement sustainability strategies while at the same time maintaining exemplary reliability. Powder flowability measurements can be valuable within this context, preventing problems with discharge from silos, bins and hoppers that can disrupt plant efficiency, particularly when using new or ill-defined raw materials. More broadly, powder flow properties are equally relevant to the ease of blending and to pneumatic conveying performance. By measuring flow properties that correlate reliably with in-process behaviour cement manufacturers can therefore gather a wealth of information to support process optimisation efforts.

2 Understanding dynamic flow testing

A primary requirement in cement manufacturing is to store powders under conditions that enable their consistent and controlled discharge. The withdrawal of material from a hopper or silo should ideally induce movement throughout the powder bulk, a flow regime referred to as mass flow. However, in many instances this flow regime fails to establish, due to cohesivity in the powder, incompatibility between the powder and the material of construction of the storage container, and the impact of system variables such as temperature and moisture. The flow properties of the powder are critical and can be enhanced through the application of a surface treatment. This can be an effective strategy for improving the flowability of very fine cements but requires careful assessment of the gain in flow performance and any detrimental impact on other aspects of performance.

Shear cell testing, a technique advanced in the 1960s, was the first attempt to bring a scientific approach to powder characterisation, and more specifically hopper design. It quantifies the strength of interactions between particles in the powder, and between a powder and the hopper wall, via parameters including Unconfined Yield Strength (UYS), Flow Function (FF), Cohesion and Wall Friction Angle (WFA). These parameters are used directly in the hopper design methodology that shear cell testing was developed to support [4] but more broadly UYS/FF are now used routinely to compare and rank the flowability of powders.

In practice, shear cell testing involves measurement of the forces required to shear one consolidated powder surface relative to another. The fact that powders are always measured in the consolidated state is important. Shear cell testing was developed to quantify the behaviour of powders under the moderate to high levels of stress that apply in a hopper and it is far less reliable for predicting the performance of powders in the low stress state. This is a critical limitation for cement applications since powders are in a low stress regime during core unit operations such as blending and most especially pneumatic conveying, when the process stream is aerated.

Dynamic powder testing is a more modern technique developed specifically to measure powder flowability under conditions that simulate the process environment. Powders can be measured in a consolidated, moderately stressed, aerated or fluidised state, depending on the process or unit operation of interest to generate relevant data for a specific application.

Dynamic properties are generated from measurements of the axial and rotational forces acting on a blade as it is rotated along a prescribed path through a powder sample, at a defined speed. A primary parameter is Basic Flowability Energy (BFE) which is measured during a downward traverse of the blade that forces the powders against the confining base of the sample vessel. BFE values quantify confined or forced flow behaviour in a low stress powder, a flow regime observed in an extruder or during die-filling. On the other hand, unconfined or gravity flow behaviour is quantified by Specific Energy (SE) which is measured by rotating the blade upward through the sample. This parameter is particularly relevant for applications such as gravitational filling.

Measuring BFE as air flows upwards through the sample directly quantifies aeration behaviour and can be particularly relevant for fluidisation and pneumatic conveying applications. Such measurements generate value of Aerated Energy (AE), a measure of flow energy at a specific air velocity. Determining how BFE changes as a function of flow (or strain), by changing the speed of rotation of blade during testing, provides valuable insight for blending studies. Some powders blend more rapidly with higher energy agitation while others, counter-intuitively, exhibit the opposite trend. Other process relevant issues such as the impact of moisture content, storage time and the effect of electrostatic charge can all be similarly investigated because of the flexibility to control test conditions.

Dynamic testing is an extremely sensitive technique. The mechanical and electronic features of the instrumentation used, in combination with well-defined, largely automated test methodologies ensure high repeatability and reproducibility and the precision to differentiate closely similar samples. Materials that are only subtly different but that will go on to exhibit different performance can be robustly identified with dynamic testing, more so than with any other powder testing technique. Furthermore, instrumentation for dynamic testing, as exemplified by the FT4 Powder Rheometer®, also enables both shear and bulk property measurement, extending its value for process-related studies. Bulk properties include bulk density, compressibility and permeability, a property that defines a powder’s resistance to air flow, that for instance can help to elucidate hopper discharge performance. The proven ability of such instrumentation to address a broad range of powder handling and processing issues makes it well-matched to the current requirements of the cement industry.

3 Experimental

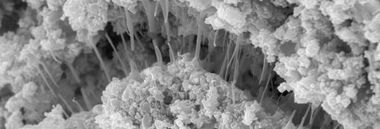

Dynamic, bulk and shear properties were measured (FT4 Powder Rheometer®, Freeman Technology, UK) for three batches of Ordinary Portland Cement with observed differences in hopper discharge and pneumatic conveying performance. Sample 1, which had a D50 of 17 µm (where D50 is the median diameter on the basis of volume), performed well in both unit operations. However, Sample 2, a finer product with a D50 of 5 µm exhibited uniformly poor performance. Sample 3 was the same as Sample 2 in terms of particle size but had been subject to a surface treatment to improve flowability and by extension process performance. Sample 3 exhibited process performance similar to that of Sample 1.

Testing was carried out using the standard protocols for the instrument [5] to generate values for AE, Compressibility and a range of shear parameters including Shear Stress, UYS, FF and Cohesion.

4 Results and discussion

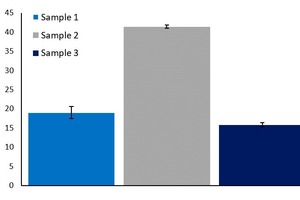

Dynamic data for the three samples show that with respect to AE, specifically AE measured at an air flow of 40 mm/s, Samples 1 and 3 are closely similar; Sample 2 generates a much higher AE.

The higher AE of Sample 2 is indicative of greater cohesive strength between the particles. Finer particles give rise to greater specific surface area and an associated increase in inter-particulate forces. At the same time the gravitational forces that induce powder flow decrease with particle mass. As a result, finer powders tend to exhibit greater resistance to gravitational flow. These data quantify the impact of these effects by assessing how the powder responds to air. The results correlate directly with observed pneumatic conveying performance and indicate that surface treatment has reduced the AE of Sample 2 to levels comparable to that of Sample 1 (as shown by data for Sample 3) by reducing inter-particulate forces.

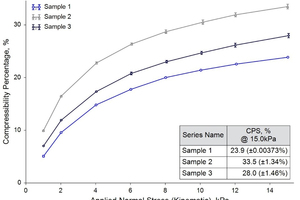

Compressibility is a bulk property that quantifies how the bulk density of a powder is changed by the application of an applied stress. Compressibility data identify Sample 2 as the most compressible cement with Sample 3 again more similar to Sample 1. These data are consistent with the preceding results since more cohesive powders tend to entrain air, which is forced out of the sample with the application of an applied stress, giving rise to high compressibility values. Less cohesive samples, in contrast, tend to pack more efficiently and exhibit minimal volume changes when subject to compressive force.

For cement manufacturers, compressibility data are primarily of interest because they inform on the potential impact of storage. Storage in large hoppers subjects a powder to significant compressive stress due to its own weight. More compressible powders are more likely to exhibit marked change as air is forced from the material, compromising flow behaviour. Here, the results suggest that surface coating has reduced the relatively high compressibility of Sample 2, with Sample 3 exhibiting much lower compressibility and the acceptable hopper performance associated with the coarser Sample 1 powder.

Shear cell data (see Figure 4) provide further confirmation of the differences between the three samples, identifying Sample 2 as the most cohesive material; Sample 2 has the highest Shear Stress, Cohesion and UYS values and the lowest FF. These data are directly relevant to hopper performance and indicate that Sample 1 will discharge more easily than Sample 2 from a hopper of equivalent geometry.

The results for Sample 3 show the same trend as observed with AE and compressibility, however, these data rank the sample as more similar to Sample 2. This suggests that surface treatment has had a less marked effect on flow behaviour at high stress. Resistance to shear can be strongly influenced by particle shape. A possible rationale for the results is therefore that although surface coating has reduced inter-particulate forces it has left particle shape essentially unchanged, thereby limiting the impact on shear properties.

5 Conclusion

Bulk powder properties, especially flowability, are helpful for predicting performance in a specific unit operation but only when measured under conditions that are representative of the process of interest, with sufficient sensitivity to detect a significant difference. The study presented here highlights the potential benefits of measuring dynamic, shear and bulk powder properties to maximise insight into the behaviour of cement samples, and the correlations between measured properties and process performance. Clear and repeatable differences are identified in the properties of two similar cements – AE, compressibility and shear parameters – that rationalise observed performance in a pneumatic conveying system and during hopper discharge. The effect of surface treatment is similarly quantified, with the data indicating the magnitude of performance improvement.

Cement manufacturing subjects materials to a range of different process environments, from aerated flow in a pneumatic conveying system to lengthy periods of compressive or vibrational consolidation in large-scale hoppers, tankers, IBCs and other containers. Powder testers that enable simulation of these environments are therefore more relevant and valuable than those that are restricted to testing over a narrow range of conditions such as shear cells. By measuring dynamic, shear and bulk powder properties it is possible to more reliably predict how a raw material, blend or surface modified cement will blend and flow throughout the manufacturing train. This is valuable information when it comes to robust process optimisation and implementation of the strategies needed to meet sustainability targets.

//www.freemantech.co.uk" target="_blank" >www.freemantech.co.uk:www.freemantech.co.uk

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.