Low temperature drying: a case study

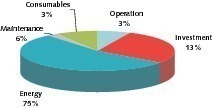

Incorporating waste treatment processes in systems in which residual energy can be utilized is one of the best residue management alternatives. With an LHV of between 2000 and 4500 kcal/kg, efficiently dried sewage sludge can be used as standard fuel, thereby reducing primary energy consumption and the CO2 quota.

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

Recently, improved wastewater treatment processes and compliance with European water quality directives have led to a spectacular increase in the amount of sludge generated by wastewater treatment processes. Suitable management of sludge is therefore at present a major challenge. Competition between this type of waste and urban waste converted into compost, combined with stricter legislation, have reduced the possibilities of using sewage sludge for agricultural purposes. This fact, along with the ban on sludge direct disposal in landfills, has led to the search to optimise methods for deriving energy from sewage sludge, which, to date, have encountered economic drawbacks mainly due to energy consumption which can represent 30 % to 50 % of the total operational costs [2].

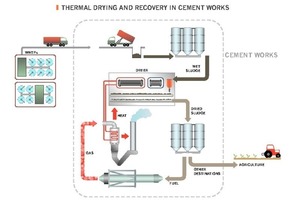

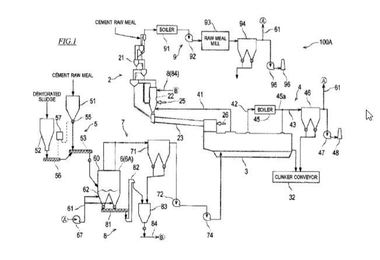

In the following an example of the complete integration of two processes is illustrated (namely sludge drying and cement production) that results in significant environmental and financial synergies.

2 Sludge recovery in the cement industry

Using sewage sludge and other types of waste in the cement industry offers certain widely acknowledged advantages – irrespective of whether the resulting energy production is utilized or not – due to the special characteristics of the cement production process. This explains the growing interest for this approach and its strong development over the past few years. The main advantages are:

the use of alternative fuels reduces the use of fossil fuels in the cement production process, as well as avoiding CO2 emissions which would have been to consider if other waste management routes were used. This leads to a reduction in overall greenhouse gases emissions both for the cement industry and the waste management industry. For example Cembureau [4] calculated that burning biofuel (or solvent waste) in a cement kiln allowed a reduction by 18 % (or 21 %) of the emissions with respect to emissions which would have taken place if this waste had been incinerated.

the cement kilns increased energy efficiency can be achieved by allowing waste to be introduced directly into the clinker without the need for intermediate processing. Ash and other kinds of waste are not generated since these products are then incorporated in the clinker.

the cement kiln operating conditions – mainly working temperature, residence time and oxidation conditions – maximise the retention of potential pollutants (such as heavy metals) without reducing the quality of the main raw material, cement.

3 Sewage sludge thermal drying

The main purpose of the thermal drying process is to reduce the sludge water content. The aim is to considerably reduce, if possible in situ, the amount of sludge generated in the treatment plants so as to facilitate its subsequent management. Therefore, the thermal drying process favours a final use for sludge, reducing the amount of product that needs to be managed, and stabilising it and therefore facilitating its storage and handling, and increasing its calorific power. After thermal drying, sewage sludge has a lower heating value (LHV) of between 2000 and 4500 kcal/kg.

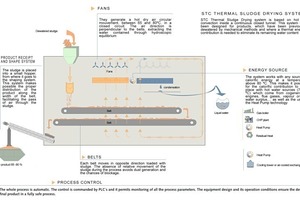

4 The STC sewage sludge drying process

The system comprises two belts. These belts convey the sludge along the tunnel, in which hot dry air circulates at a temperature of 65–80 °C and perpendicular to them. This air, propelled by the ventilation system, goes through the product extracting the water by means of hygroscopic equilibrium. The returned moist hot air is condensed in exchangers inside the tunnel, eliminating the water separated from the sludge and supplying new heat energy, so that the air is recirculated and the pro-cess is maintained in a closed air circuit.

It must also be noted that the low-temperature drying process prevents the stripping of other pollutants retained in the sludge, ensuring that they do not return to the water. As a result, only high quality water is obtained, with very low entrainments that depend on the kind of the sludge treated.

5 The drying process energy supply

cogeneration systems: not only exhaust gases are used, but also engine cooling water and low energy level exhaust gases (50 % of the heat produced by a cogeneration engine), until the maximum efficiency permitted by the engine is reached.

produced within other heat processes, such as exhaust from incinerator chimneys, turbine condensation heat, gases from gasification processes, etc.

heat pumps or similar technologies can be employed.

heat from renewable energy sources can be used, such as solar energy (hot water at 80 °C), geo-heat, etc.

6 Integration in a cement plant

7 Results

For water agencies, the management process is improved in environmental terms, since there is no need to locate a new site. It is also improved in financial terms, due to more efficient overall process management costs – as the final destination for the sludge is guaranteed – and reduced operational costs due to the heat supply (since no primary energy source is required to carry out the process).

Companies operating sludge treatment plants benefit from an installation with an environmental impact that is compatible with the cement production, reduced energy costs (since primary heat energy is not required), preferential electricity costs, and a guaranteed final destination for sludge. In addition, this type of process does not rule out the use of other solutions, such as agricultural use or sludge disposal in a landfill, as reductions in the quantity of product requiring handling and water content facilitate sludge management. As for environmental impact, the cement factory allows all sludge treatment plant equipment to be connected to a general deodorising network. Since the combustion of the off-take gases of the dryer takes place in the kiln, no odours are emitted [5] to the atmosphere, making this one of the most effective odour treatment processes available, free of any capital or operational costs.

The following environmental indicators can be achieved, based on a heat content for the substituted coal of 26 GJ/t and a ratio of 93 kg of CO2 per ton of coal:

waste energy from the cement factory used for thermal drying the sludge, implying 46 million therms gained annually, equivalent to around 18 000 t of CO2

energy supplied by the sludge combusted in the kiln (mean calorific power of 3000 kcal/kg of dry sludge) implying 53 million therms gained annually, equivalent to 20 500 t of CO2

8 Conclusions

This type of process provides an important environmental improvement opportunity for cement factories, since it increases energy efficiency; in other words, a greater proportion of useful energy for the same primary energy consumption effectively pre-empts the need to purchase CO2 quotas.

Sludge with a water content of less than 20 % and acquired without primary energy consumption has an increased energy recovery potential. With an LHV of between 2000 and 4500 kcal/kg, it can be used as a standard fuel, thereby reducing primary energy consumption and the CO2 quota associated with substituted fuels. This integrated sludge drying and cement production system has been assessed as a reliable, viable route for sludge management, allowing for significant reduction of greenhouse gases emissions both for the cement industry and the sludge drying process.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.