Automation technology and trends in the construction materials industry

The construction industry can take advantage of automated manufacturing processes and new technologies.

If you look at industrial...

If you look at industrial plants, you will quickly notice that many forms of energy play a more or less important role depending on the industry. One thing that is common to all industries is the considerable influence that these energy carriers have on the price of the end product and thus its position in the market. If a company succeeds in constantly putting these influencing factors to the test and optimizing them, it will obtain and solidify its own market position and simultaneously make a decisive contribution to environmental protection. Thus, the appropriate automation technology makes an important contribution toward protecting the environment, using energy and raw materials efficiently, and reducing emissions.

Development and reasons for automation

Then as now, the main reasons for automating a process or production plant are:

Improvement and homogenization of product quality

Cost reduction (personnel, energy, resources)

Increase of the throughput rate

Relieving personnel of monotonous or heavy physical labour

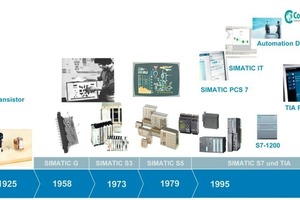

In the beginning, the application of automation technology was limited to large-scale production lines. Today, it is also possible to automate even small plants through the use of more flexible automation technology. The first electronic controllers were hard-wired systems. The flexibility was correspondingly low and the functionality was extremely limited. The new transistor, with its signal amplifying function, triggered a real boom in automation. As early as 1955, Siemens developed the first control circuits using germanium transistors.

In the mid 1970’s, the transition from wired to PLC technology led to a change of paradigms in control technology. The control task was now saved as software in the form of programs and blocks. This allowed changes to be made independently of the hardware and increased functionality, which opened up completely new applications for automation technology.

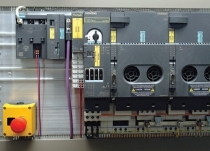

In the mid 90’s, the introduction of “Totally Integrated Automation” in the Siemens AG portfolio provided an additional impetus: Characteristics such as integrated configuration, integrated data management, and integrated communication now determined the competitiveness of an automation solution. Topics such as operator control and monitoring, communication via bus systems and networks such as Profibus or Industrial Ethernet, and integrated engineering in distributed automation structures also became increasingly important. Automation and drive technology were largely independent sectors until the mid 90’s. Only the general use of fieldbuses and their functional expansion to include isochronous operation and direct data exchange between the sectors created the basis for the increasing integration of drives and automation. Now it became possible not only to program connected controllers from a programming device or PC, but also to implement “intelligent drives” via one and the same bus.

This meant that it was no longer difficult to also integrate the distribution of electric power within an automation system into the automation concept. Today, the “Totally Integrated Power” portfolio from suppliers like Siemens ranges from planning tools to a coordinated hardware portfolio: From switchgear and distribution systems for medium voltage to transformers, switching and protection devices as well as switchgear and busbar trunking systems for low voltage, all the way to small distribution boards and cables and connectors. The products and systems can be safely connected to the automation system over almost any distance via communication-capable switches and interface modules. This allows exploitation of the entire optimization potential of an integrated automation solution with regard to energy consumption, from planning, configuration, programming and installation to operation.

Goal: Digital factory

Today’s software tools rely on a common interdisciplinary and consistent database, which integrates the various engineering data from mechanics, electronics, and automation into one plant structure and intelligently manages modularity, standardization, and library concepts. In the process, the software overcomes the previous boundaries between all of the participating disciplines and combines the mechanical, electrical, and control related system planning for a time-optimized layout and engineering phase and the consistent documentation of a production plant.

Regardless of the tools used in the planning process, all of the data is compiled in a digital engineering system and used further in a uniform user interface in the operational process chain; this ensures uniform data management, from planning to production.

Such software tools (e.g. the “Life Cycle Engineering and Plant Asset Management” Comos) also allow automated, standardized working, the reduction of coordination effort, and an increase in the quality of the results with considerably less effort thanks to, for example, the reduction of transmission errors. Due to the object-oriented structure of the software, it is possible to respond quickly to individual requirements and parts of the application that have already been created can simply be re-used. This ensures current and consistent documentation, which can be called up at any time during the creation and operation of the plant.

Automation example in the preparation

of bulk materials

Extensive, partially concealed and difficult to access sub-systems with a frequent need for maintenance are the typical application area of wireless Simatic Mobile Panels. Wireless communication was not used in quarries in the past, because it was feared that the radio waves might be subject to interference from the many steel supports, beam constructions, and silos. Two access points – one at the pre-crusher and one near the silos – specify the effective ranges and are currently completely sufficient for operating the Mobile Panel (Fig. 4) at all relevant points in the system. A third access point is provided for expanding the system.

The HMI software (Simatic WinCC) for simple and clear visualization runs on both the Multi Panels and on the Mobile Panel. The display and operating options of the Mobile Panel are identical to those of the two stationary panels. The plant operator receives current diagnostic messages from the entire system in this way, allowing him to respond immediately and thus prevent or at least considerably reduce downtimes. The work that previously required two plant operators can now be carried out by just one so that his co-worker can take on other important tasks. This not only increases productivity, but also operational reliability.

Another example of modern automation technology in the construction materials industry is the open-air, contact-free level measurement (Fig. 5) of bulk materials [2]; ultrasound technology is extremely well suited for this. Ultrasound is ideal for these applications because:

the rugged, encapsulated sensors are extremely resistant to shocks and vibrations

their highly active sensor/transmitting surfaces are self-cleaning in slightly dusty environments

the narrow beam angle of each ultrasound sensor can be aligned to a specific level of material

Further potential areas for developing

automation technology

the continuing, progressing decentralization

the continuing advances of Ethernet at the field level

the increasing intelligence of the field devices and drives, resulting in diagnostic and maintenance capabilities

new, low-cost sensors

the increase in wireless communication

the further vertical integration with company-wide networking of operational processes

the optimization of plant processes (Advanced Process Control)

the increasing use of energy management systems

Wireless communication with Ethernet at the field level

Energy management systems and optimization

of plant processes

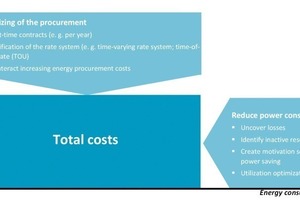

There are four possible optimization paths for electrical energy alone:

When optimizing systems, it soon becomes clear that losses can only be detected if the consumption levels of the different parts of the system are known in detail and can be compared. Modern energy management systems are based on standardized components, which are present in large numbers in the system and can thus be easily and effectively used for recording. In addition to recording the electrical energy, all of the other forms of energy should also be recorded in order to create overall transparency, because energy management is implemented at many levels in an industrial plant. Beginning with the field level, the required basic data is acquired via corresponding “sensors” in order to later be prepared and compressed in the assigned controllers. This data is now made available to the operators. This also includes the defaults of the load management for the connecting and disconnecting of plant units. The control center personnel can generally accept these defaults or refuse them (during critical system situations) or move them within value range (temporarily).

Procuring the required energy is becoming an increasingly important topic, especially for energy-intensive industries such as the cement industry. In this case, the purchasing department needs sound scenarios which illustrate the process as precisely as possible. This also includes, for example, modules that allow various consumption profiles to be calculated in order to also be able to optimize in sub-areas. An operator will only be able to qualitatively plan his budgets if he is in a position where he can create correct energy forecasts. This planning security puts the end consumer in a strong position to be able to negotiate effectively with the energy supplier. If an energy schedule is negotiated with terms of purchase, this schedule can be sent via the system’s energy management system to the load management system. Even if an energy management system was introduced into a system, the optimization work is still not finished: Actually, only the basics, i.e. the aids and tools, were created for getting closer to the actual goal of an energy-efficient system.

Modern automation technology in cement plants also provides support (Fig. 7) in the energy management of secondary fuels. Intelligent software modules (e.g. the Cemat Fuel Manager from Siemens) can be integrated into existing control systems relatively easily, in order to optimize the fuel dosing of primary and secondary fuels in such a way that (here too) the burning process is highly efficient and energy costs can thus be reduced.

Stabilizing quality and saving time

All of these measures must be regularly checked and improved in order to remain competitive, to efficiently operate a system/plant, and to also meet legal requirements. Throughout the entire process chain, described only in part here, from the crushing of the raw material to the end product of a cement mill, it will always be the observant worker who recognizes further potential areas for saving and who uses them for additional measures. Thus, the appropriate automation technology makes an important contribution toward protecting the environment, using energy and raw materials efficiently, and reducing undesirable emissions.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.