Trends in cement kiln pyroprocessing

Plant engineering companies supplying the cement industry have recently started talking about plants oriented to the needs of the customer. Attributes such as “tailor-made” or “standardized” seem to be a thing of the past.

1 Introduction

Dry process with preheater and calciner

Most usual plant sizes between 3000–6000 tpd

Specific heat consumptions of < 725 kcal/kg cl (5-stage preheater)

Specific electrical energy requirements < 90 kWh/t

Automatic plant...

1 Introduction

Dry process with preheater and calciner

Most usual plant sizes between 3000–6000 tpd

Specific heat consumptions of < 725 kcal/kg cl (5-stage preheater)

Specific electrical energy requirements < 90 kWh/t

Automatic plant control for high availability and quality

Use of alternative fuels

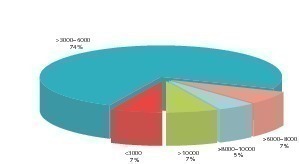

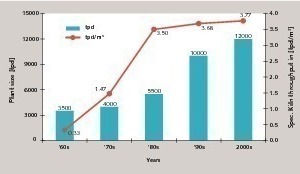

2 Development of kiln capacities

In the last trend report on kiln technology [2] the so-called “project phasing” of kiln systems was mentioned. This means that the customer does not purchase one large kiln line, but installs two or more smaller lines at different points in time. Such smaller lines can have capacities of over 4000 tpd – as shown by the example (Fig. 3) of the Egyptian Cement Company (ECC, today Lafarge). At ECC, five lines with a total production capacity of 10 million tonnes per year (Mta) were installed within a period of less than 5 years. The new installed capacities were suited to market demands and the company quickly achieved a high capacity utilization after the construction of each new line. If only one or two large lines had been installed, it would not have been possible to achieve capacity utilization after their commissioning.

3 Customized plants

For many years, kiln systems in the cement industry were regarded as individual, custom-tailored solutions [2]. The main reasons for this were the widely differing raw materials and fuels that were used, the different environmental regulations, the different locations and standards, and also the plant capacity and energy requirement figures that were precisely specified by the investors and owners. When Chinese vendors entered the market at the end of the 1990s and started quoting on an EPC contract basis (EPC = Engineering, Procurement, Construction), a trend towards standardized plants commenced. The focus was not placed on absolutely precise cement plant or production line design but rather on the conditions for so-called “plant and design-build” deliveries. The general conditions for such turnkey deliveries are specified by organizations such as the FIDIC (Féderation Internationale des Ingénieurs-Conseils) [3].

Standardized kiln systems of this type were initially only sold in China. Outside China, the first standardized 2500 and 3000 tpd systems were primarily sold in third world countries. Later, systems with sizes of 4000, 5000, 6000 tpd and up to 10 000 tpd followed. However, customers in the more western-oriented markets refused to accept purely Chinese technology. As the Chinese vendors did not have their own state-of-the-art vertical mills, clinker coolers, burner systems, high-capacity conveying systems, dosing systems, silo systems and automation and measuring systems etc. [4], they had to integrate such technology mainly from Western European sources. Despite this, the concept of standard cement plants with specific sizes and standardized technology was retained. Customers entering into EPC contracts with Chinese suppliers did so because of the comparatively low prices.

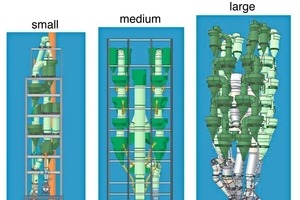

In the meantime, the established western kiln suppliers have progressed to the stage where they are able to establish customer-oriented solutions from their existing system. These are based on a modular system, permit different technological options and are very close to the optimum solution for each individual customer. The possible variations with regard to plant size (Fig. 6), technology, fuels employed, environmental standards, automation concept etc. are considerable, but can already be reliably covered. Different company standards and process engineering design parameters such as the determination of dew points still have a considerable influence. This can cause significant extra expenditure with consequences ranging up to the need for larger foundations [2].

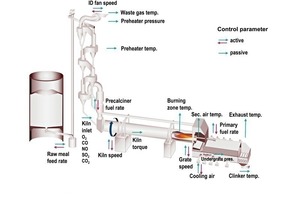

4 The kiln system

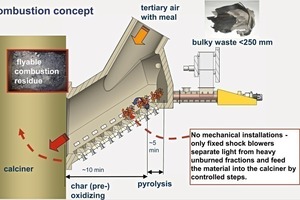

Polysius developed the Step Combustor as a combustion chamber for large-sized refuse materials. This combustor ensures feed material retention times of up to 15 minutes. This system has a static inclined step grate and the material is moved along by shock blowers (Fig. 8). Up to 70 % of the calciner fuel can be fed in via the combustor. KHD also employs a combustor for refuse derived fuel (RDF) and other types of fuel. This is designed for temperatures of above 1200 °C. It is increasingly expected that such combustors should be able to process shredded high caloric fraction refuse material < 300 mm and should not require preparation to sizes < 80 mm, as is the case with conventional combustion chambers.

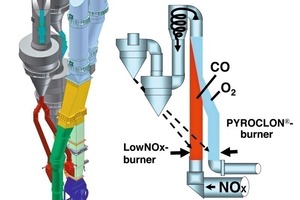

With modern calciners, reduction zones and multi-stage combustion facilitate effective NOx reduction (Fig. 9). An interesting point is that all the vendors make practically exclusive use of inline calciners. In the case of inline calciners not only the tertiary air but also the kiln exhaust air is completely routed through the calciner. Separate-line systems differ in that the kiln exhaust air flows directly into the bottom cyclone preheater stage. Inline calciners can achieve emission levels < 500 mg NOx/Nm3 of exhaust gas. In many cases, this means that there is no need for a downstream SNCR-NOx reduction process (selective non-catalytic reduction).

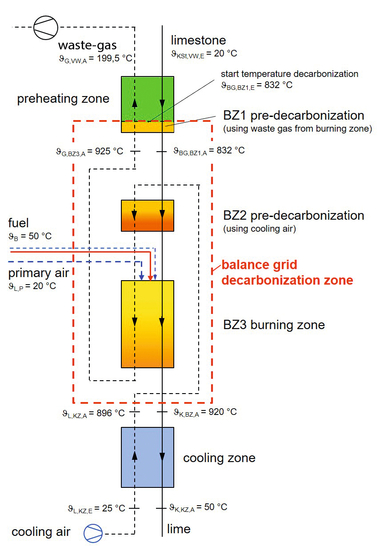

The typical heat losses of a kiln line with 6-stage preheater are shown in Figure 10. The heat of reaction makes up the main portion of 57.1 %, followed by 20.7 % for exit gas heat losses, which can however be recuperated for material drying purposes or for power generation by using, for example, waste heat recovery (WHR) systems [5]. The cooler losses of 16.4 % are mainly due to the heat loss of the clinker, which has a temperature of approx. 100 °C when it leaves the cooler. The radiation losses (SHL = surface heat loss) of the rotary kiln and the preheater/calciner are comparatively low, at 4.3 and 5.0 % respectively. The specific heat values of the raw meal and fuel are counted as inputs. At a heat consumption of, for example, 2930 kJ/kg clinker, these inputs reduce the heat consumption by 3.6 %.

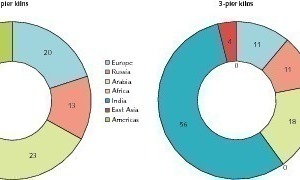

Due to the fact that 95 % of the calcination takes place in the preheater and calciner, there is no calcining zone in the rotary kiln, which can therefore be dimensioned smaller, making the kiln cheaper. 2-pier kilns with L/D ratios of 12–13 have correspondingly become very popular for small and medium kiln capacities of up to 6000 tpd. For more than 10 years now, some of these kilns have been equipped with self-aligning supporting rollers and friction drive via the rollers, so that no girth gear is needed. Since 2004, KHD has sold slightly more 2-pier than 3-pier kilns (53 % to 47 %). However, regional preferences are interesting for both variants (Fig. 11). In America, only 2-pier variants have been ordered in the recent past, while Indian customers have only purchased 3-pier variants. Due to the use of secondary fuels, a trend towards somewhat longer rotary kilns has again become noticeable.

Modular design is more extensively applied to modern grate coolers than to the other kiln system components. This makes it possible to run the kiln with different output rates and modes of operation [6]. Today‘s clinker coolers are exclusively designed as grate coolers because this allows the extraction of secondary air as combustion air for the kiln and the extraction of tertiary air for the calciner. By providing recuperated secondary air for the kiln and tertiary air for the calciner, grate coolers thus supply the entire combustion air for the kiln system except for the burner air. However, they also have to smooth out the fluctuations from the rotary kiln, the loosening of coating rings and any other malfunctions in the burning process without aggravating these via the combustion air.

5 Burner technology

To make burners suitable for use with different secondary fuels, it is expected that they burn secondary fuels with a more intensive and compact flame than primary fuels. This requires higher flame temperatures in order to ensure the highest possible degree of combustion, but these high temperatures must not affect the clinker quality. Moreover, the high flame temperatures promote thermal NOx bonding, which is also undesirable and must be prevented. On the other hand, not many parameters are available to the manufacturer for burner optimization [8]. These are the air stream distribution, the mode of swirl generation, the method of fuel feeding and mixing of combustion air and swirl air and, naturally, the air pressures used for the burner setting.

The results published of recent burner developments [e.g. 9–12] show that manufacturers have succeeded in reconciling the diverse and sometimes contrary demands. It is reported, for example, that the new Novaflam burner (Fig. 12) from Pillard allows a reduction in kiln inlet temperature, cuts NOx generation, reduces the electrical power requirement for operation and permits more stable rotary kiln operation, thereby reducing operational interruptions and ultimately ensuring that the burner is more easily settable. Naturally, such experience reports need checking. However, the reports being issued by the leading burner manufacturers generally indicate that although demands are nowadays more complex they can be very largely fulfilled by improved technology.

6 Prospects

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![10 Heat losses of a kiln line [1]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/tok_4c2fe165a2a752fccf4df8e8c1f5055b/w300_h198_x155_y99_101530390_44cc4d6674.jpg)