Secondary fuels in cement production

Summary: Alternative fuels have become a trend topic all over the world. This is partly due to the increase in price of conventional fuels and partly to the discussion about resource conservation and climate change. What contribution can the cement industry make? This report presents background facts and experience gained in the cement industry. Its purpose is not only to deal with the technological aspects but rather to explore the economic and ecological considerations. It particularly discusses the cost-effectiveness and ecological benefit of waste co-processing in cement plants and what developments are currently taking place.

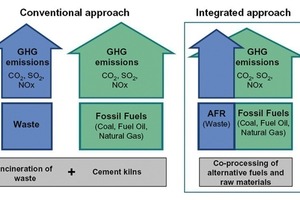

Western Europe is a world leader in the utilization of alternative fuels in the cement industry. The concept of “Co-Processing” was propagated as long ago as the beginning of the 1990s and within a few years was developed to the point of practical application in numerous cement plants [1, 2]. In contrast to separate refuse incineration and cement production, the utilization of alternative fuels instead of conventional fossil energy sources in the form of waste co-processing in the cement plant has proved to be an effective way of reducing the emission of such greenhouse gases as...

Western Europe is a world leader in the utilization of alternative fuels in the cement industry. The concept of “Co-Processing” was propagated as long ago as the beginning of the 1990s and within a few years was developed to the point of practical application in numerous cement plants [1, 2]. In contrast to separate refuse incineration and cement production, the utilization of alternative fuels instead of conventional fossil energy sources in the form of waste co-processing in the cement plant has proved to be an effective way of reducing the emission of such greenhouse gases as CO2, SO2 and NOx (Fig. 1). The waste materials are referred to as AFR (Alternative Fuel and Raw materials). Depending on the AFR usage rate, conventional fuel substitution rates of 0 to almost 100% are conceivable or already implemented or are in the process of implementation. Waste co-processing involves no alteration of the actual cement manufacturing process.

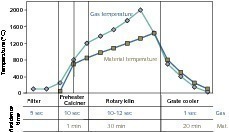

The cement burning process is ideal for the incineration of waste materials (Fig. 2). This is firstly due to the high burning temperatures of up to 2000°C, which assure the decomposition of even those dangerous organic compounds that are difficult to destroy. Another reason is that the residence time in the kiln system of gas with a temperature above 1000°C is 10–15 seconds, which is long enough to also assure complete oxidation of the materials. As solid fuel materials have a residence time of 30 minutes, an adequate degree of burnout is always assured. The combustion residues or ashes are completely integrated in the material cycle of the system and utilized for the production of the clinker phases. The retention rates for trace elements in the clinker phase are very high, being just under 100% for chromium, copper, manganese and nickel. Only in the case of mercury is the retention rate generally below 80% due to its high rate of vaporization.

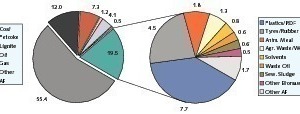

Taking the example of the Heidelberg

Cement Group, Figure 3 shows which conventional and alternative fuels are in use. Although hard coal, lignite and petroleum coke are still the most important energy sources, the amount of alternative fuels employed has meanwhile reached approx. 20%. Plastics and other mixtures containing plastics from waste treatment plants (RDF = Refuse Derived Fuel), which are also called fluff (Fig. 4) (fluff = gas-entrainable

materials), already make up about 40% of alternative fuels, followed by waste tyres and rubber scrap (23%), animal meal (9%) and waste wood and agricultural materials (7%). Solvents and waste oil make up a 7.2% portion. HeidelbergCement and other major cement producers are promoting the use of so-called biofuels, as these are regarded as environmentally neutral with regard to CO2 emissions. Apart from animal meal,

biofuels particularly include waste wood, other biomass and sewage sludge.

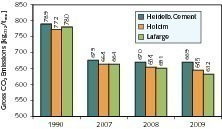

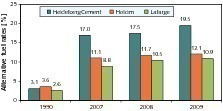

The leading cement producers have voluntarily undertaken to drastically reduce their CO2 emissions. 1990 was selected as the reference year. Figure 5 shows the global values achieved so far by Lafarge, Holcim and HeidelbergCement. Compared to the reference value of 780 kg CO2/t of cement in 1990, Lafarge has already achieved a reduction of 19% to 632 kg CO2/t of cement. But also HeidelbergCement and Holcim, with their reduction rates of 15.2% and 16.5% respectively, are at the forefront of the cement industry. The target reduction figure of 15% between 1990 and 2010 has thus already been exceeded. In principle, there are only three ways to achieve further reductions. Increases in efficiency or reductions in the specific fuel requirement per unit of clinker produced can only save a few percentage points. A further reduction in the clinker factor is very largely determined by the marketing prospects for environmentally friendly cement types.

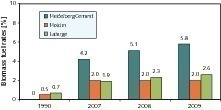

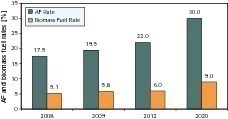

Increasing the employed usage rate of alternative fuels remains a tried and proven means of reducing the CO2, and is particularly effective if CO2 neutral biomass is used as the fuel. The rates of alternative fuel use of the three largest cement manufacturers are shown in Figure 6. HeidelbergCement leads the cement industry with its current alternative fuel usage rate of 19.5%. High alternative fuel usage rates increase the profitability of the cement production plant. The usage rate of CO2-neutral biofuels is shown in Figure 7. According to this parameter, HeidelbergCement again leads with a current usage rate of 5.8%, which also means that the company‘s net CO2 balance is improved. In contrast, Holcim and Lafarge only achieve biofuel usage rates of 2% and 2.6% respectively, with stagnating or only slightly increasing trends.

In Europe there are extensive statutory regulations governing the emission limit values that are to be observed when using alternative fuels and the method of plant operation monitoring. EU countries are subject to the IPPC directive (2000/76/EC) regulating waste burning in industrial plants. This directive was incorporated in the national laws in 2002. In Germany, for instance, the limit values are governed by the “TA Luft” (Clean Air Act) and additionally by the regulations of the 17th regulation of the Bundesimmissionsschutzgesetz (17. BImSchV) (Federal Immission Control Act). The limit values stipulated in them include total dust, heavy metals, sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides, gaseous inorganic compounds, dioxines, furanes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAK) and other compounds. Depending on the types of fuel used, there are different requirements regarding the emission concentration limits that have to be complied with. For cement plant operators it is sensible to keep the usage rate of hazardous waste material below 40%.

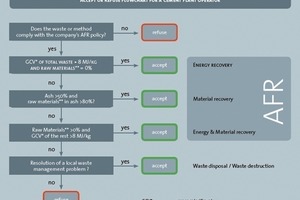

The market development has led to the usage of a large number of different alternative fuels. In a joint venture with Holcim, the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) in Eschborn developed criteria for the co-processing of waste material in cement plants [3]. A number of usability requirements were defined for AFR material (Fig. 8). The most decisive of these is the material’s usability as an energy supplier, but its usability as raw material or a combination of usability as energy supplier and raw material constituent are also of interest. The method of fuel handling in the cement plant largely depends on the pre-processing of the material, the range of different fuels and the employed fuel quantities. The pre-processing is an important process stage in waste preparation, and is performed by external companies or separate business units of the cement manufacturing firm. Preparation of waste at cement plants is not desired.

A number of waste handling solutions are employed at cement plants. Handling of tyres and rubber wastes (Fig. 9) in automatic operation requires complex material feeding and separating units. Liquid fuels such as waste oil are far easier to handle and dose (Fig. 10). Solid fuel mixtures such as RDF demand a greater amount of equipment (Fig. 11) [4]. Different alternative fuels are delivered via so-called docking stations for truck trailers (Fig. 12). Continuous supply to the burner becomes problematic if not enough buffer volume is available. Enormous halls are needed for the storage of large quantities of alternative fuels and an adequate buffer volume (Fig. 13). The downstream processes are primarily determined by the nature of the dosing devices. In modern systems, multi-material dosing systems are generally used (Fig. 14). Correspondingly high demands are also placed on the calciners and multi-fuel burners [5–7].

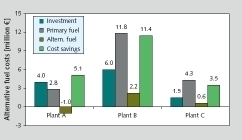

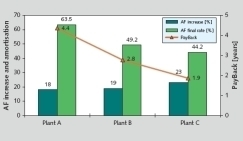

The question of profitability of co-processing plants can be explored by taking HeidelbergCement as an example. The alternative fuel usage capacities of three HeidelbergCement plants have recently been extended [8]. Figure 15 details the capital expense for the system extensions (mainly storage and dosing systems), the fuel costs, and the costs saved by using alternative fuels. Figure 16 shows the amortization costs of the plant capacities. This figure underscores the general tendency that the higher the already achieved alternative fuel usage rate is, the more expensive it is to achieve a further significant effect. Accordingly, the plant capacity of plant A was expanded by less than 30% and that of plant C by more than 50%. However, in addition to this, local influences such as fuel sourcing exist.

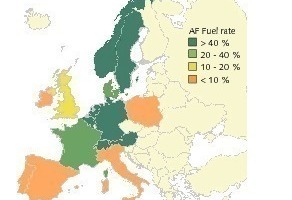

Europe‘s leading role in the co-processing of waste materials in the cement industry is undisputed. However, within Europe there are strong regional differences (Fig. 17) and there is a distinct north-south divide. In Europe, the rate of conventional fuel substitution by alternative fuels was still 3% in 1990, but this rose to approx. 12% in 2000, approx. 19 % in 2005 and approx. 25% in 2009. In Germany, the cement industry is currently achieving a substitution rate of 58.4%, i.e. 2.8 million t of alternative fuel. The first experience with alternative fuels was gained as long ago as the 1950s, when used tyres were burnt for the first time in Germany, although conventional fuels could still be purchased cheaply at that time [9]. Also in Germany, the so-called BRAM concept (= RDF/Refuse Derived Fuel) was introduced during the second oil crisis at the end of the 1970s. Meanwhile, environment and climate protection are a progressively greater motivation for the co-processing of waste materials, in addition to the increasing economic pressures [10].

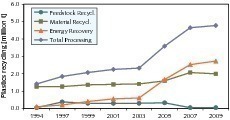

The progress in Europe would not have been possible without the efforts made by cement producers through the establishment of their own waste processing companies (e.g. the Holcim company Geocycle (Fig. 18) and HeidelbergCement‘s ecorec and SRM with their products such as Cemfuel), as well as the cement industry‘s utilization of other resources, particularly plastic wastes. In Germany, for instance, the amount of waste plastics increased from 2.8 million t (1994) to 4.93 million t (2009). Figure 19 illustrates the development of waste co-processing. Meanwhile, utilization as an energy source has become the most important segment, while utilization as a raw material constituent plays no role at all. If one ignores the recycling of plastics as a production feedstock, 2/3 of waste plastics in the post-consumer sector in Germany go into utilization as an energy source. 40% of waste plastics are used as an alternative fuel while 60% are burnt in refuse incineration plants.

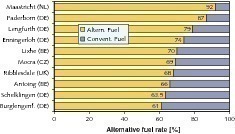

The German-speaking countries and the Benelux countries are regarded as the leaders in the co-processing field. This also becomes clear on a plant level when one considers e.g. the TOP locations of HeidelbergCement (Fig. 20). This figure shows that most such locations are situated in Germany or in the Benelux countries. Only two locations in the TOP10 are situated in other countries. The Maastricht plant (Fig. 21) occupies 1st place in the internal HeidelbergCement ranking with a 92% alternative fuel usage rate. The plant fires large amounts of dried and ground sewage sludge. This sewage sludge is prepared by the so-called Biomill process and has a calorific value of 12 GJ/t, i.e. an energy density 7 times higher than that of pre-dewatered sewage sludge [11]. However, other HeidelbergCement plants use wet sewage sludge. Sewage sludge is a popular way of increasing the usage rates of biomass wastes.

At the Lägerdorf plant (Fig. 22) of Holcim Germany, the alternative fuel usage rate is currently 75%, representing 70% of the energy input [12]. Fractions with high calorific value from municipal, industrial and commercial wastes make up the lion‘s share of these alternative fuels, but even rotor blades from wind energy plants are processed and used. The utilization of fluff and alternative fuel pellets help to minimize the firing of brown coal, for example. Holcim recently applied for an approval procedure to increase the plant‘s AFR usage rate to 100% in 2011. This increase will be partially covered by the use of sewage sludge. The company is planning for a usage of 50000 t (DM) per year. The fuel portion of the AFR will correspond to about 11% of the plant‘s total firing capacity of 240 MW. Dried sewage sludges are delivered in bulk transporter vehicles while dewatered sewage sludges are delivered in semitrailers. The environmental impact assessment has already been submitted for this project.

5 Progress in emerging countries

Every country and practically every cement factory has its own chances and possibilities for the co-processing of waste ma-terials. The ability to utilize knowledge from other projects all around the world is an advantage. Among the most important prerequisites are the existence of corresponding statutory directives, the obtaining of a licence and the installation of suitable storage and dosing equipment for the kiln system. One of the problems involved in the co-processing of wastes in these countries is that there are few incentives, hardly any dumpsite controls and little awareness of the advantages of cement plants compared to environmentally problematic refuse incineration plants. The consequent lack of financing, lack of technological infrastructure and weaknesses in the application of statutory requirements are the main reasons why the possibility of environmentally-friendly waste disposal in cement plants has so far been only inadequately exploited [13].

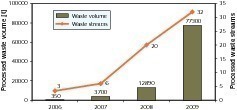

However, despite the fact that important cement production countries such as China, India, Pakistan and Turkey are only just starting to use waste materials for co-processing and their average substitution rates are still only around 5% or even less, there are a number of success stories of individual producers and plants. India has recently adopted guidelines for co-processing plants in the cement industry [14]. Beside companies like Grasim, Birla Corp., HeidelbergCement and Lafarge, ACC is one of the pioneers on the co-processing field. Figure 23 shows the rapid development of waste co-processing at ACC. While only three different types of waste material with a quantity of just under 350 t were used in 2006, ACC‘s waste usage rate already exceeded 77000 t in 2009 and the number of waste materials employed had risen to 32. The company obtains a large portion of its waste material from industrial sources which otherwise are unable to dispose of their wastes – which sometimes include hazardous substances – in an environmentally-friendly manner [15].

The rising cost of conventional fuels is being particularly felt in countries like Pakistan, where the cement industry has to import almost 90% of its fuels. Fuel costs therefore make up over 40% of the production costs. As most Pakistani cement plants are located in the north of the country, overland transport costs of around 25–30 US$/t are incurred in addition to the marine shipping costs of about 90 US$/t (CIF Karachi Seaport).Numerous cement producers are already using biofuels such as rice husks as an alternative fuel. Fauji Cement, who operate a 3700 tpd plant (Fig. 24) in Jhang Bahtar in the province of Punjab, was among the first companies in Pakistan to use RDF for co-processing. Their RDF firing capacity is still around 12 tph. The fuel preparation takes place in the cement factory. Up to now, the company has gained very good operating

experience with the system and intends to use this option at its new 7200 tpd plant.

Most emerging countries have without doubt made pro-gress with their environmental laws and guidelines for waste co-processing in cement plants, even if emission limit values are, in some cases, still considerably higher than the strict EU limit values. But it is particularly in these countries that cement plants facilitate environmentally beneficial waste disposal, in contrast to, for instance, the poorly-equipped refuse incineration plants. The leading global cement producers are providing a good example by using the same Best Practises in emerging countries as they do, for example, in Europe. Consequently, the emission figures of these firms’ cement plants in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Argentina are far below the permitted limit values in those countries.

The potential for co-processing in the cement industry is far from exhausted. This applies equally to the industrialized countries of Europe and North America and to the emerging countries. HeidelbergCement is planning to increase its usage rate of alternative fuels from the present 19.5% to 30% by 2020 (Fig. 25). Naturally, this aim will be most easily achieved if the usage rates in emerging countries like China and Indonesia can be drastically increased. The company is also planning to raise its usage rate of CO2-neutral biofuels to 9%, in order to cut the CO2 load of its cement production. It is interesting that, according to HeidelbergCement, the cost of alternative fuels significantly decreases in line with an increasing usage rate. The use of alternative fuels will be significantly promoted if other companies follow Holcim‘s example by developing their own resources in individual countries around the world for the purchasing and preparation of alternative fuels.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.