Lean manufacturing and thermal enhancement of single-layer wall with an additive manufacturing (AM) structure

The emergence of large-scale additive manufacturing (AM) technology has been increasing around the world. This large-scale AM technology has facilitated several projects using cement-based materials. AM technology can theoretically be applied in modern construction but much work is still required for further investigation and implementation in the field of lean manufacturing practice. This work describes the AM of textured single-layer wall panels assembled to form a guardhouse structure. The innovation in this structure lies in the design of the textured single wall layer that is not generally found in existing AM textured walls. The benefit of using lean manufacture for the AM textured single wall panel is the reduction in weight; 10 to 11 % less material is required. Another benefit found in the architectural design and surface textures of the AM structure is the considerable improvement in the thermal properties and the 31 % energy saving when compared with the conventional design.

1 Introduction

For many decades the research and development programmes for large-scale additive manufacturing (AM) or 3D printing technology in such domains as design, construction, and architecture have been using various types of materials, such as plastics [1, 2], metals [3], ceramics [4], wood [5], asphalt [6] and cement-based materials [7-11]. The attention of academics, construction material producers, architects, and contractors is becoming increasingly drawn towards large-scale AM technology. Large-scale AM technology results in many benefits through the increased degree of...

1 Introduction

For many decades the research and development programmes for large-scale additive manufacturing (AM) or 3D printing technology in such domains as design, construction, and architecture have been using various types of materials, such as plastics [1, 2], metals [3], ceramics [4], wood [5], asphalt [6] and cement-based materials [7-11]. The attention of academics, construction material producers, architects, and contractors is becoming increasingly drawn towards large-scale AM technology. Large-scale AM technology results in many benefits through the increased degree of customization and superior construction efficiency. Many attempts have been made to implement robotic systems for various construction applications such as Prefabricated Prefinished Volumetric Construction (PPVC) and prefabrication construction. However, this work focuses on real-time construction using the AM technology.

Large-scale AM technology is also considered as a revolution in the construction industry. This is because of the importance of the reduction in labour shortage issues and the advancement of digital innovation. Such technology ideally offers several benefits to the civil engineering and architectural design industries, including [12-14]:

(1) Leaner production

(2) Reduced construction waste

(3) Expansion of customized design

(4) Enhanced process accuracy

and minimized errors

(5) Improved overall quality of work

(6) Safer operation

The benefits of using the AM technology in civil engineering and architectural design are well established so several traditional and alternative construction materials have been developed to tackle the labour shortage issue, including the use of alternative binders, ultra-high performance concrete, fibre-reinforced cement, aerated cement, and geopolymers [15-20]. There are several successful AM technology procedures, such as extrusion (also called fused deposition modelling; FDM), binder jetting and smart dynamic casting technology [21]. The extrusion AM technology is based on extruding a fresh material though a nozzle in layers until a printed element is fully formed. The binder jetting technology is based on laying a dried powder material and then spraying a liquid/slurry binder to form the designed element. The smart dynamic casting is a novel construction technique for fabricating a mesh-like fibre-reinforced formwork and spraying a fresh concrete mix onto the formwork. Much work has shown that the performance characteristics of material printed by a large-scale binder jetting printer using cementitious materials can be as good as those of the material printed by large-scale extrusion machines [22-27].

These three AM technologies have their own advantages and limitations, depending on the criteria for the fabrication of the printed elements. The correct technology can therefore be selected for the particular application.

One of the key aims of the technology developers is the in-situ construction of a multi-storey house or building. This requires multiple skills, including materials science and architectural design. The AM printing process, AM printing machine and its AM algorithm from computer-aided design (CAD) software, finite element modelling from structural analysis software, and fabrication and jointing processes are required to print the house. A five-storey showcase apartment building with an area of 1100 m² has been unveiled by the Winsun Company in Suzhou/China as shown in Figure 1 [28]. However, the building was constructed by printing the panels and connecting the printed wall panels on site (in-situ printing of the complete house was not achievable). However, Dini aims to print an entire house structure with a compressive strength at 28 days of at least 20 MPa by using a D-shaped AM machine with a printing volume of 12 x 12 x 10 m, as shown in Figure 2 [29, 30]. Many research and development programmes for eventually attaining the goal through a more efficient process are still under investigation.

It is often said that the cement-based materials developed for extrusion AM have distinctive characteristics that differ from traditional concrete because it must be possible to extrude the material through a nozzle typically ranging from 1 cm to 5 cm. The unique key characteristics of AM concrete include:

Printability: The printability characteristics of the fresh mix is directly related to its various rheological properties (plastic viscosity and yield stress) as well as to the pumping and extrusion system used (diameter, material type, geometry of the nozzle head, pumping distance, type of pumping hose and the pressures applied by the screw conveyor and pump system, etc.) The printability of the fresh AM mix can be varied by adjusting the superplasticizers [30-32], the geometry and size of the aggregate and the viscosity modifier [33]. It should be noted here that the fresh mix is generally mixed for a longer mixing time that depends on the mixing and pumping system. The issue of loss of flowability must be taken into account in the printability of the fresh material. Many research programmes [34-36] investigated longer mixing times and higher rotational speeds and reported that the fresh properties of the mix were altered but that the negative effects could be reduced by the presence of chemical additives and supplementary cementitious materials (SCM).

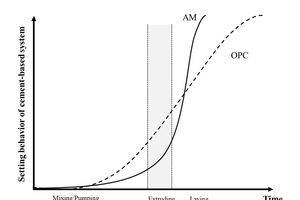

Layability: Once the fresh mix has been extruded from the nozzle, the next property to be considered is the layability. The mix is printed in layers, so the stiffening/setting behaviour or thixotropic state should develop gradually so that multiple layers can be supported without dramatic deformation and subsequent collapse. Many additives can be used to tailor the layability of the extruded mix, including alternative hydraulic binders [37-41], chemical accelerators [42, 43], retarders [44] and clay [45-46]. Figure 3 shows the desired setting behaviour of the fresh AM mix when compared to an ordinary Portland cement (OPC) mix. The early-stage setting behaviour of the fresh AM mix should last longer before the stiffening stage to keep the rheology unchanged and allow the mix to be extruded. The extruded mix should then develop its strength relatively rapidly after it starts to stiffen. This ensures that the extruded mix can support multiple layers.

High compressive strength: The AM concrete mix has a higher compressive strength than normal concrete. Hambach and Vokmer [25] reported that the normal compressive strength of the concrete was about 20 to 60 MPa but could be as high as 80 MPa when the alignment method of short reinforcing fibres is used. Le et al. [26] developed a 3D printing concrete that was printed using a 9 mm diameter nozzle and had compressive strengths ranging from 75 to 102 MPa. Gosselin et al. [27] developed a 3D printing concrete that contained micro silica and had a compressive strength as high as 120 MPa. The concretes referred to in these studies can be considered as ultra-high performance concretes. The developments in terms of materials science in the cement-based materials seems promising since the strengths are high enough for constructing houses and buildings.

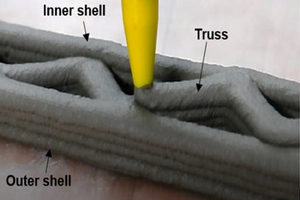

One of the commonly considered aspects in large-scale AM extrusion technology is the path design for the extrusion direction. When printing an AM wall structure it is usually found that the structure of the panel is formed as double-layer shells with an inner truss inside the shells, as shown in Figure 4.

The inner truss is designed to support an internal load. This work describes a novel printing solution for a wall system by printing single-layer wall panels. This novel solution of a single-layer wall is based on a lean manufacturing principle resulting in a lower weight of the structure, reduced printing time and the utilization of less material, which generates economic and operational benefits. The competitiveness of large-scale AM technology can be enhanced with all these benefits and can eventually be equivalent to a conventional construction process, such as prefabricated construction. This paper also presents the results of the thermal performance of an AM structure built as a guardhouse. It demonstrates the significant advantage with respect to thermal performance when the structure is formed from AM panels. The textured single-layer wall panels of the guardhouse (referred to as a “Triple S - Surface, Structure, and Shelter”) are designed to have a woven pattern [45]. After printing using the AM extrusion machine, the printed panels are combined to form the guardhouse structure. The surface temperature of the structure exposed to outdoor conditions was measured in situ for comparison with the former conventional guardhouse that was replaced by the new one.

2 Research methodology

2.1 Materials

The AM cement mixes have distinctive performance characteristics as discussed earlier [17]. The AM extrusion material used in this study was therefore formulated in-house. It was composed of ordinary Portland cement, fly ash, silica fume, hybrid fibres, alumina cement, crushed limestone aggregate and retarder. A more detailed assessment of the properties can be found in Snguanyat et al. [9]. The mixes contained calcium sulfoaluminate cement or calcium aluminate cement as the accelerator in the approximate quantity of 0.1 to 5.0 % by weight to allow for the overlap of the bottom layer relative to the next layer. The relationship between the degree of overlap and the geometry of the printed layer are shown in Equation 1. The increased degree of overlap leads to a more textured AM structure, which allows for greater flexibility and variety of design for the mixes printed by the AM process.

⇥(1)

The fresh and hardened performance characteristics of the AM mixes are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that the workability time means the period for which the mixes can be extruded through the nozzle.

A self-levelling non-shrink grout (SCG non-shrink grout, Thailand) was obtained locally and was required during the construction. Its specification is shown in Table 2. It was needed for jointing each panel. A two-component epoxy sealant (Sikadure-32TH, Thailand) was obtained locally for sealing the joints of each panel. A shaped steel bar with a diameter of 12 mm sourced locally was used for connecting the joints of each panel.

2.2 Methods

This section describes the methods employed in the three processes, including the AM process for the guardhouse structure, evaluates the lean manufacturing practice and assesses its thermal performance.

2.2.1 The AM process for the guardhouse structure

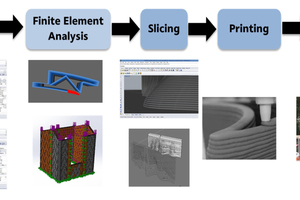

This article describes the AM process methodology shown in Figure 5. The process begins with the modelling of the printed element, followed by conducting finite element analysis to evaluate the structural performance. The design modelling was conducted using CAD software (Rhinoceros 3D version 5, Robert McNeel & Associates). The structural design of the guardhouse was then carried out using a CAD engineering program (SolidWorks 2015, Dassault Systèmes). After the structure had been analyzed structurally, the solid model was transferred to the slicing software to slice the model into layers. The thickness of each layer can be controlled as required and the direction of travel of the extruding nozzle is designed by the slicing software (Cura; Ultimaker Cura). After the slicing process, the sliced model was transferred to the controller of the AM machine and the printing operation was started. The AM process was carried out using a DeltaWASP customized machine (WASP project). The printing area was approximately 2 m in diameter with a height of about 2 m. A plastic nozzle with a diameter of about 5 mm was attached to the printer. The layer height used was approximately 5 mm. The printing process was continuous and ended when the printing of each element was completed. It should be noted here that there is a limitation on printing size. The size of the guardhouse was 3.0 x 3.5 x 3.5 m; more details can be found in [47]. This size was much larger than the printing volume of the machine. The guardhouse was therefore designed to be split into smaller elements. Fabrication and jointing processes were required for each element during construction. When all the panels had been printed they were stored until their strength had developed sufficiently for lifting and withstanding the loads. All the panels were then delivered to the site, lifted, and assembled.

2.2.2 Evaluation of the lean manufacturing practice for AM single-layer wall panels

This section describes the lean manufacturing practice used for the novel development of printing an AM single-layer wall. Lean manufacturing appears to hold considerable promise for addressing the competing demands of quality, flexibility, cost, and time deliveries and has a direct impact on incremental and radical process innovation. Lean manufacturing can promote the options for radical process innovation, such as the large-scale AM technology described in this study for exploiting the construction market [48, 49]. AM technology on a large scale is still at the frontier of commercialization so lean manufacturing through product and process design can significantly improve the value-to-market of the product since these product and process activities reportedly represent about 80 % of the total design work. The benefits of fabricating the AM single-layer wall panels when compared to the AM double-layer wall panels assessed in this work include reduced material usage and printing time [50]. After the installation of the guardhouse had been completed the estimated total weight of AM mix used for fabricating the single-layer wall panel was evaluated in comparison with the AM double-layer wall panel. The total weight of AM mix printed is shown in (2) and (3).

V = L∙t∙w∙n⇥(2)

W = ρ∙V⇥(3)

Where

V = total volume of AM mix used (m³)

L = average path length for 1 layer (m)

t = thickness of each layer as specified in design model (m)

w = width of the extruded mix after extrusion (m)

n = number of layers

W = total weight of AM mix used (kg)

ρ = density of the mix (kg/m³) as shown in Table 1.

The total time for printing the AM single-lay wall panel was calculated and the time for printing the AM double-layer wall was also approximated as a reference. The calculation of the total time of printing is shown in (4).

⇥(4)

where

T = total time for printing the panel (h)

A = constant time value in relation to the preparation and after-work time (h)

h = height of each layer as specified in the design model (m)

R = rate of printing (kg/h); in this work it ranges from 100 to 150 kg/h. It should be noted that the R value depends on the AM system used

2.2.3 Evaluation of thermal performance

The thermal performance of a building is a major consideration and is obviously a prime factor in achieving energy efficiency. Suitable choices in the determination of the construction materials utilized, in designing the layout of the building, in locating windows and partitions and in fabricating the wall systems could maximize the thermal efficiency of the building. This not only contributes towards reducing the required size of the air-conditioning system but also towards reducing the annual energy costs [51, 52]. In an average home in the US, for example, the air-conditioning and cooling systems account for about 50 to 70% of the total energy consumption in the home [53]. By reducing this large percentage the thermal performance of buildings can help to reduce the serious problems of climate change. Two components that greatly influence the thermal performance of the building are 1) the thermal conductivity of the chosen construction material and 2) the architectural design and wall systems of the building.

The thermal behaviour of cement-based materials is relevant to their use in buildings, bridges and other structures. In particular, a high value of the specific heat is desirable due to the associated ability to retain heat while a low value of the thermal conductivity is desirable due to the associated ability to provide thermal insulation. However, a high thermal conductivity value can be desirable due to the associated ability to reduce the temperature gradient, and hence the thermal stresses, in a structure. The thermal conductivities [W/m K] of the AM panels were tested in accordance with ASTM C1167 [54] and compared with that of a normal OPC mix containing pulverized fly ash with a designed compressive strength of 40 MPa. The OPC mix proportions were designed for a prefabricated panel with binder content of more than 425 kg/m³. After casting, the panels being tested were cured under saturated humidity conditions for 28 days before assessing their thermal conductivity. Duplicate samples were assessed and the mean value was recorded.

The thermal performance of the AM guardhouse was evaluated here to show the reduction in energy consumption when the AM single-layer wall was used. The in situ temperature measurement was conducted under outdoor conditions. The panels were exposed to the sunlight during the day. The surface panel investigated was located on the east side so that it was exposed to direct sunlight during the morning. The surface temperatures of both the inner and outer walls were recorded at ten-minute intervals using thermocouples (PL-90-11; Tokyo Sokki Kenkyujo; Japan) embedded at the centre of each panel with a data logger (TDS-540; Tokyo Sokki Kenkyujo; Japan). The equipment had a measurement range of -10°C to 200°C with an accuracy of ± 0.5°C or ± 0.5%. The data were collected for approximately 5 days.

After all the data had been collected the thermal contact conductance coefficients of both the conventional and the AM guardhouses were calculated. The thermal contact conductance is the thermal property showing the conduction of heat between two solid bodies in contact. [55] The thermal contact conductance of the AM panel can be calculated from Equation 5 based on the Fourier principle.

⇥(5)

where

q = heat flow

k = thermal contact conductance coefficient

A = cross sectional area

= temperature gradient at the contact

3 Results and discussion

3.1 AM process for the guardhouse

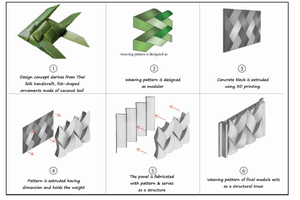

Figure 6 shows a schematic outline of the architectural design process. Step 1 in the diagram begins by creating the design concept derived from a hand-crafted fish ornament (from Thai folk handicraft). The ornament is typically made of coconut leaf. The weaving pattern of the fish ornament is then designed on a modular basis so that it can be printed as a panel (Step 2). The design of the 3D printing concrete panel is then transferred to the printer in Step 3. This is followed by extruding the concrete panel using the 3D printer (Step 4) and the 3D printing concrete block is then fabricated with the concrete pattern (Step 5). This final modular weaving pattern can withstand loads and also acts as a structural truss (Step 6). It should be noted that the design concept based on the lean manufacturing principle comes first, followed by implementation of the concept of the hand-crafted fish ornament.

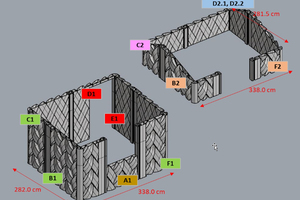

Figure 7 shows the AM process and the hardened surfaces of the textured single-layer AM wall panel. The fresh AM mix is designed for printing with curves and can be overlaid without any support. It was found that final surface of the guardhouse had no hair cracks or shrinkage cracks after more than 12 months in service. As mentioned above, there are limitations to the AM machine so the sizes of the AM panels are also limited. The design model of the guardhouse is divided into 11 elements as shown in Figure 8. The code for each printed panel is identified. It should be noted that one aspect for future improvement with respect to the lean manufacturing principle is the acquisition of a larger AM machine system with more efficient processes, such as automatic mixing and feeding systems. This would eliminate the fabrication process of multiple AM panels as illustrated in [33, 56] and the labour costs for mixing the concrete could be reduced.

The printing duration and weight of each printing element are shown in Table 3. The total weight of all elements is approximately 4900 kg and the total printing time is 52 hours. An accelerator is used in the cement mix. This reduces the time delay while waiting for the strength of the element to develop sufficiently before it is transferred. Acceleration of the various cement-based materials could be beneficial for the operating time and promote the competitiveness of the construction method. After all the elements have been printed they are transferred to the site [36, 57]. Each element is assembled as designated. The non-shrink grout is mixed with water to give the correct flow properties and is then poured in at the corners and other parts of the elements. The two-part epoxy is mixed and applied at the joints between the elements. Figures 9a) and 9b) show the former guardhouse built using a typical construction process before it was demolished and the textured single-layer wall guardhouse printed by an AM extrusion machine. Completion of the AM guardhouse with respect to all the printing and assembly processes took 2 to 4 weeks.

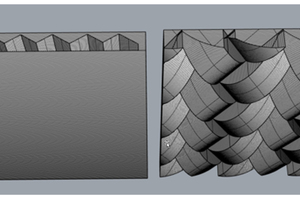

3.1.2 Evaluation of the lean manufacturing procedure for an AM single-layer wall panel

This section describes results of the improvement resulting from the lean manufacturing procedure for developing the AM single-layer wall panels. The results for an AM single-layer wall panel are compared with those for an AM double-layer wall panel, as shown in the models in Figure 10. The modelled panels of both systems have dimensions of 1.3 x 2.0 x 0.12 m. The AM mixes were extruded with a width of 2.5 cm and thickness of 1 cm. Two aspects are considered: the reduction in material consumption and the reduction in the total time for the printing process. The weight of mix consumed was calculated in (2) and (3) and the total time of printing was calculated in (4).

The results of the weight of printed material and the time for printing the AM single- and double-layer wall panels are given in Table 4. The results indicate that the weight of the printing materials for the AM single-layer wall panel is approximately 11 % lower than for the double-layer wall panels. This is because the outer shell is eliminated for the single-layer wall panel, so less material is consumed. The total time for printing the two AM systems was also assessed and the estimate indicates that the total time for printing the single-layer wall panel is 10 % less than for the double-layer wall panel. The procedure for producing the AM single-layer wall panel is faster and more efficient than for the double-layer wall panel.

It can be concluded that the architectural design of the novel AM model of the single layer wall panel, as originally conceived, leads to a leaner manufacturing process in term of materials consumed and time spent. It should be noted that although both the process parameters for printing the AM single-layered wall panel are reduced, this does not take account of other beneficial indirect activities, such as reduced labour costs, transportation costs, and electricity and energy costs. The actual benefits achieved are very significant and may exceed the estimate. More research is required to examine the overall procedures for printing the single-layer wall panel based on the lean manufacturing processes.

3.1.3 Evaluation of thermal performance

The AM and the precast mixes were cast in moulds with a thickness of 10 cm. After the specimens had been cured for 28 days they were assessed for their thermal conductivity properties. The results in Table 5 indicate that the AM and precast mixes had thermal conductivity values of 0.54 and 0.43 W/m K respectively. The thermal conductivity of the AM mix is 26% higher than that of the precast mix. In terms of material conductivity this means that the heat flux can be transferred between the layers of the AM mix faster than in the precast mix. This is thought to be due to the ingredients of the AM mix as detailed in [9]. The ingredients of the cement mixes were studied [58-60] and it was found that the cement content, silica fume, fly ash, polymer, fibre, cellulose, and aggregate all had a significant impact on thermal conductivity. The replacement of silica fume and fly ash could reduce the thermal conductivity of cement-based systems by up to approximately 40 % while the increased content of fine aggregate could result in an increase in thermal conductivity by about 60 %. The AM mix contains fine aggregate and also the said mineral and chemical additives so it has a higher thermal conductivity than the precast mix in which the ingredients include pulverized fly ash as well as coarse and fine aggregates. The higher thermal conductivity value of the AM mix is thought to occur because the density of the hardened AM mix (2400 kg/m³) is higher than that of normal-weight concrete or the precast mix. Although the thermal conductivity of the AM material itself is higher than that of the precast materials it should be borne in mind that the thermal contact conductance value is another contributory factor in the complete building system.

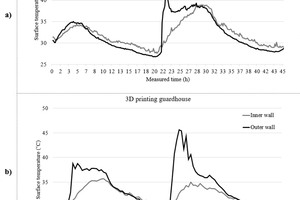

Figures 11a) and 11b) show an example of the results (over about 2 days) of the in situ measurement of the surface temperatures of the inner wall and outer wall of the former conventional guardhouse that has been demolished and of the AM guardhouse. The experiment was carried out over approximately 5 days. The earlier days saw the air temperatures ranging from approximately 25 to 35˚C and the later days had air temperatures between 27 to 42˚C (i.e. higher than the former). The panel surface of the outer wall investigated was exposed to the sun during the morning. This period shows the highest surface temperature value at the outer wall.

The following indicators with respect to the thermal performance of the guardhouse are included in the assessment:

1) The maximum surface temperature of the inner wall, indicating the decrease in the temperature at the highest level inside the structure when using the AM technology

2) The kinetics of the internal temperature rise, indicating the rate at which the heat is transmitted through the AM panel of the structure. The slower the kinetics the better is the heat insulation system

3) The relative thermal contact conductance coefficients based on (5)

4) The relative energy consumption based on the calculation by Zhou et al. [61]. The relative energy consumption (C) is calculated from (6)

⇥(6)

where

∆T = maximum temperature of inner wall

Tavg = average daytime temperature

(= 35˚C in Thailand)

Teco = temperature setting generally adopted for

air-conditioning systems during summer(= 26˚C in Thailand)

The results of all the indicators measured are listed in Table 6. These show that for the AM guardhouse the maximum temperature of the inner wall is 4.7˚C lower than for the conventional wall even though the maximum temperature of the outside of the AM wall is 2.5 ˚C higher than with the conventional wall. It can be seen that the colour of the AM mixes is darker than the conventional mixes. The lightness (L*) value of the hardened AM mix is 53.2, whereas the L* value of the hardened conventional mix is 70.9 based on the CIELAB colour space test. The higher L* value contributes to the lighter colour of the measured object. The kinetics of the temperature rise at the outer walls of both systems are not significantly different, ranging from 5.4 to 5.9˚C/h. It should be noted that the surface temperature rises to its maximum when the panel is directly exposed to the sunlight. This indicates that neither system has a significant difference since the temperatures at the outer surfaces still rise at a similar rate. However, when the surface of the inner wall is considered, the temperature rise kinetics of the AM structure are 66% lower than with the conventional structure. The dramatic reduction in the kinetics of temperature rise is due to the fact that not only is there a space gap between the outer surface and inner shell, but the surface of the AM structure also is rougher and more textured. Zavarise and Paggi [62] and Lambert and Fletcher [63] reported that the surface roughness of the solid material at the macro and microscopic levels could significantly affect the thermal conductance properties. The measured surface temperature data show that the AM structure can save almost half the energy consumption of the conventional structure. This large energy saving percentage when using the AM structure reflects a significant benefit with respect to the thermal performance. It can be concluded that although the material of the AM mix has a higher thermal conductivity than the conventional precast mix (as shown in Table 5) the design of the space gap between the wall and the surface texture plays an important role in establishing the thermal conductance of the system. The architectural design and surface texture derived from the AM technology have a significant effect on the thermal performance, leading to huge savings in energy consumption.

4 Conclusions

This study describes a large-scale AM process for fabricating the AM guardhouse and its benefits in terms of lean manufacturing practice and energy saving. However, it seems that at present the large-scale AM process is unlikely to replace existing technologies such as prefabricated construction. There will have to be considerable work on investigation and improvement in this field. The novel AM process of printing a single-layer wall panel instead of a double-layer wall panel will represent a further step in improving the process with respect to reducing the amount of material used and time spent. In the case of the AM guardhouse this procedure can save up to approximately 11 % of the total material used and 10 % of the total time required for the printing.

As far as the thermal performance is concerned, although the AM mix contains various ingredients that increase the thermal conductivity by 26 % when compared to the conventional OPC mix this can be more than offset by the architectural design of the space gap and the rough/woven surface texture derived from the large-scale AM technology. The thermal contact conductance of the AM structure is 69 % lower than that of the conventional structure, leading to savings of 31 % in energy utilization. The positive contributions from the lean manufacturing principle and the thermal performance of the large-scale AM promote the efficiency of the process and the savings in energy consumption are such that this technology could represent a major revolution in the construction industry.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

![1 AM five-story building in China [28]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/2/2/0/6/2/tok_7c14f924e80543a225290226443bda22/w300_h200_x286_y163_Application_Siam_bild1-e176c50389d3846b.jpeg)

![2 Outline of the entire house printed by a large-scale D-shaped machine [29]](https://www.zkg-online.info/imgs/1/4/2/2/0/6/2/tok_f7aaf97fee6c960278dc240a74a0fae9/w300_h200_x287_y226_Application_Siam_bild2a-047717f5bc8eb990.jpeg)