Leading safety with numbers

Currently in occupational safety, mainly lagging indicators are used, such as LTIFR (Lost Time Injury Frequency Rate), which means measuring something negative, namely the absence of safety. These indicators are based on a high number of working hours, do not support benchmarking and give little clue to root causes. It would be better to work with leading indicators that help to predict incidents and find causes. First-aid cases and near misses could be such indicators, leading to preventive action.

1 The challenge

All companies explicitly or implicitly promise all their employees a work environment free of harm as part of the employment contract so that they leave their workplace as healthy as they had arrived at it. This makes safety at work a management obligation.

Peter Drucker, one of the great management thinkers in the last century, stated back in 1954: “The first task of top management of a business enterprise is to develop clear concepts and usable measurements” [1]. Today, there are a series of clear concepts for safety at work, among them “Vision Zero” [2], developed by ISSA...

1 The challenge

All companies explicitly or implicitly promise all their employees a work environment free of harm as part of the employment contract so that they leave their workplace as healthy as they had arrived at it. This makes safety at work a management obligation.

Peter Drucker, one of the great management thinkers in the last century, stated back in 1954: “The first task of top management of a business enterprise is to develop clear concepts and usable measurements” [1]. Today, there are a series of clear concepts for safety at work, among them “Vision Zero” [2], developed by ISSA (International Social Security Association) and already adopted by many important companies around the world. The cornerstone of this concept is its seven golden rules. The third rule states that companies must set safety and health targets. Today, every company has to check if it has developed not only clear concepts but also usable measurements. The challenge in developing indicators is to define what “usable” means in the context of safety at work.

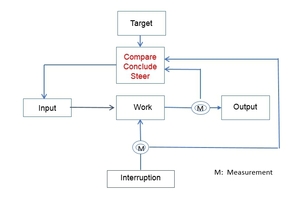

In general terms, numbers are useful for management when these allow it to set targets, to measure the outcome and then to compare both, to draw conclusions for this comparison and to use those conclusions to steer the next cycle (Figure1). Steering always means looking into and trying to influence the future.

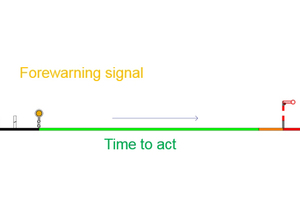

Reaching and maintaining a safety target of zero, however, requires a distinct emphasis on prevention, similar to quality management but with a higher urgency since safety deals with the wellbeing of humans and not “just” fault-free products for consumers. To prevent future harm, we need forewarning signals, just like a train driver so that he can halt his train in time if another train is standing on the same track. To prevent incidents, management needs predictive indicators as early warnings, that allow conclusions on where, when and how to act to prevent employees, contractors and visitors from harm (Figure1).

2 Usefulness of today’s indicators

In literature and the internet the safety indicator that always turns up is the Lost Time Accident Frequency Rate (LTAFR), sometimes termed LTIFR (Incident instead of Accident, which makes sense because accident sounds too much like accidental and there is nothing accidental about incidents).

This frequency measurement, calculated either on 200 000 or on 1 000 000 work hours, is used all around the world by companies and authorities alike. In terms of safety, leading companies achieve a LTIFR of ≤ 2 (basis: 1 000 000 manhours). Companies are obliged to include this indicator in their reports.

This, however, does not mean it is a “useful indicator”. Apart from lacking stringent standards regarding its measurement (especially in the definition of when an accident is an accident), its main deficiency is that it is a lagging indicator, showing harm that has already been done. Tom Krause wrote back in 1980: “The reliance on accident frequency as the sole measure of performance shows up for what it is – misleading and reactive” [3].

3 Developing leading indicators

For the development of predictive (or leading) indicators suitable as early-warning signals, the questions are: What are the obligations of management, the obligations of the employees, and which incidents should be analysed?

3.1 Indicators derived from management

obligations

Regarding safety, the obligations of management include doing HIRAs (Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment), developing SWPs (Safe Working Procedures) and keeping SWPs current. From this the following indicators can be derived:

of HIRA/# of defined activities⇥[~1]

of HIRA revised / month⇥

⇥(> 16% [= twice each year])

of SWP/# of defined activities⇥[≥1]

of version differences between activity description and SWP⇥ [~0]

3.2 Indicators resulting from

employee obligations

In respect of HIRAs and SWPs, employees have the obligation to know, understand and accept them as well as working according to the SWPs. From this, the following indicators can be derived:

of SWP trainings completed⇥(~ 100%)

Participation in Safety Moments⇥(> 95%)

of Safety Moments given⇥(> 95% of target)

of Safety Observation tours done⇥

⇥(> 95% of target)

3.3 Indicators resulting from the Bird Pyramid

The pyramid in Figure2 is named after Frank E. Bird Jr. who undertook in 1969 a study to determine the ratios of various types of incidents [4] and shows a definition of harm according to severity. They are as follows:

First Aid Cases (FAC) and Near Misses (NM) can be analyzed according to types of activities, locations (geography), time and experience level of persons involved, pointing to possible hot spots where preventive action should be intensified. Looking at the time element for example, FAC and NM reporting can show whether the probability of harm is higher, for example, the morning after major sport events or in early winter with its higher consumption of over-the-counter cold remedies. A good FAC/MN reporting furthermore enables middle management to find root causes and gives them material to deliver at their daily safety moments.

4 Making FAC/NM reporting possible

First Aid Cases are frequently only captured “statistically” without the necessary detail to enable conclusions to be drawn. Near Misses are registered even more rarely.

For change, three major hurdles must be overcome:

the early conditioning of humans not to “wake sleeping dogs”

the reluctance to put things in writing and

the inefficiency of processing data into information

4.1 The sleeping dog hurdle

Already at a very young age, we learn not to report near misses. We all remember situations in kindergarten or classroom like this:

Not to report misbehaviour if there was no serious consequence is deeply ingrained in our minds as numerous sayings starting with “Let sleeping dogs lie” mentioned above to the German “Whenever grass has grown over an issue and hides it, a camel comes along to eat it away”.

Squealing or telling on others is generally frowned upon, while telling on yourself is regarded as just plain dumb.

The situation described shows the dilemma for a worker who has infringed a rule but not harmed anyone. If he could be punished for his infraction, then he most certainly won’t reporwt it.

What can and should be done to remove this hurdle to receiving the information? The USA’s National Safety Council recommends: The reporting system needs to be non-punitive and, if desired by the person reporting, anonymous [5]. This recommendation is fully consistent with many other publications on this topic. It, however, raises another issue for the management. On one hand a company needs to enforce company rules, which in turn includes consequence management, i.e. punishment. On the other hand, the recommendation states the contrary, implicitly saying that the information resulting from near miss reporting is so valuable that the company should not enforce rules whenever by “luck” the potential for damage and harm has remained just a potential. As a consequence, companies will punish results and not cause. This dilemma cannot be eliminated and should be discussed extensively with the workforce. One approach could be to set a time limit of, for example, 24 hours for reporting incidents that will not be subject to sanctioning. The non-punitive approach helps to encourage all employees involved to report near misses that are the result of their own rule infringement, without dispensing with penalties completely. Denouncing another person should, however, remain a taboo in order not to create an informer culture usually associated with totalitarian states. In a healthy company culture, employees observing a co-employee infringing a rule should talk to the other employee and encourage them to report it.

4.2 The red ink hurdle

The second issue, the reluctance to write things down, also has to do with early conditioning.

40 years later and the situation hasn’t changed, particularly because the workforce in many firms is now multinational. It’s enough to read reports filled out by plumbers, electricians or painters coming to fix something to see that the language is rarely correct.

It is therefore important to create a reporting system in a company that does not require written text. Several opportunities exist. The most usual solution is to use a form structured as a checklist that demands only the employees to tick boxes. Such forms, however, require that the safety experts reviewing the forms must go back and do interviews since checklists do not carry the full information. Another solution is to nominate somebody good at writing to serve as the reporter; employees know that they can see him at certain times to tell their story. Depending on the smart phone policy of a company, an app can be prepared with which employees can enter whatever they want to report together with a photograph. The reluctance to write is much reduced with the use of a smart phone because text may be corrected automatically and Twitter-like messages have a grammar of their own, anyway.

4.3 The feedback hurdle

The final hurdle is the efficiency in dealing with the reports since in large facilities there can be easily hundreds of reports per month (especially if the bottom category of the Bird pyramid, unsafe conditions and unsafe behaviour, is included). Reports must be analysed, preventive measures designed, decisions taken, and actions implemented. This process is the logical consequence of the near miss reporting, the purpose of which being to take preventive actions to stop the root causes leading to harm.

There should, however, be a second process that gives feedback to the person who reported an incident and the workforce soon after the report is submitted. Employees want to be taken seriously and to know that the bosses have received the report and are doing something about it. Krause [3] has shown that consequences that follow soon and are clear to grasp have a big positive impact. Companies looking at their Near Miss Reporting need to analyse whether their feedback process is fast and clear enough. This, however, does not mean jumping to conclusions. Some reports need time to be fully analysed; some solutions might need to go through a full investment approval process. In such cases, giving feedback can mean that the company informs the person who has reported that a process has been started and that content-oriented feedback will be given at such and such a time.

5 Conclusions

The safety world relies to a large extent on lagging indicators today. These are necessary since target setting makes only sense if the results reached are measured against the targets. Lagging indicators, however, are not sufficient since they do not help much in guiding and focusing the preventive actions that aim at avoiding incidents.

We need leading indicators that can predict serious incidents. First Aid Cases and Near Misses are such leading indicators. Consequently, all companies should set up and introduce a good reporting system for them.

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.