Carbon capture, utilization and storage in the cement industry

Cement and concrete are the most important construction materials but the manufacturing industry is also one of the largest industrial CO2 emitters. Accordingly, the EU plans to reduce the CO2 emissions by 80 % by 2050, when compared with 1990.This article highlights relevant facts & data about the global and European cement industry, what measures are taken for the mitigation of emissions, what are the most promising technologies and what are the prospective costs.

1 Introduction

In the cement industry, unlike most other industries, the process chemistry (decarbonisation of the limestone) rather than fuel combustion and electricity consumption is responsible for almost 2/3 of the CO2 emissions in clinker manufacturing. However, this proportion even increases with more advanced technologies that reduce fuel and power consumption. As an example: in the EU in 1990 the CO2 emissions from decarbonisation made up only about 54 % of the 170 million t (Mt/a) from the cement industry, combustion was responsible for about 38 %, power consumption for about 6 % and...

1 Introduction

In the cement industry, unlike most other industries, the process chemistry (decarbonisation of the limestone) rather than fuel combustion and electricity consumption is responsible for almost 2/3 of the CO2 emissions in clinker manufacturing. However, this proportion even increases with more advanced technologies that reduce fuel and power consumption. As an example: in the EU in 1990 the CO2 emissions from decarbonisation made up only about 54 % of the 170 million t (Mt/a) from the cement industry, combustion was responsible for about 38 %, power consumption for about 6 % and all others (incl. transport) for about 2 %. Today, it is estimated that the proportion from decarbonisation in the cement industry of the EU is close to 60 %.

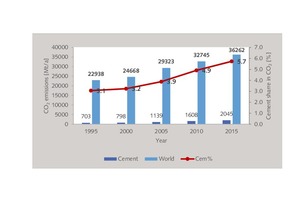

Due to the large rise in cement consumption and production, CO2 emissions from the cement industry grew faster than those of other industries (Figure 1). The CO2 emissions of the cement industry almost tripled in the 20 years from 1995 to 2015, while the share of the cement industry in global CO2 emissions increased from 3.1 % to 5.7 % and is probably now close to 6 %. Figure 2 shows the development in the different regions of the world. Asia is the region with the largest absolute growth (+1170 Mt/a of CO2) and largest relative growth (+234 %), while Europe is the only region with a negative growth (-7.7 Mt/a, -6 % relatively). The Middle East and Africa also had a significant growth (+84.5 Mt/a and 53.5 Mt/a respectively in absolute figures, and +186 % and +174 % in relative figures).

According to the IEA, the cement industry was responsible for 2094 Mt/a of CO2 in 2010, and the emissions decreased to 2021 Mt/a by 2016. It is not possible to confirm whether this is true because on a global scale the effects from the increase in cement production were probably larger than the reducing effects due to better thermal and electric efficiency, use of alternative fuels, a lower clinker to cement ratio (clinker factor) and lower cement production in North America and Europe. However, as regards the CO2 emission level, cement comes second after the iron & steel industry, which had about 2500 Mt/a of CO2 emissions in 2010 (Figure 3).

The chemicals industry and oil refineries together are responsible for another 2.0 M/ta of CO2, while the aluminium industry only accounts for 0.1 Mt/a.

Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technologies will have their price. For the cement industry in Europe, where average cement prices are as high as 100 €/t, the price of 20 €/CO2, either due to the EU trading scheme or the costs for CCUS, will cause a 17.3 % rise in the commodity price (Figure 4). This effect will increase to 25.9 % at 30 €/t, 43.1 % at 50 €/t and finally to 86.3 %, if the price for 1 t of CO2 increases to 100 €. The cement industry in Europe will no longer be competitive on an international scale and will lose market shares to imports. Similar increases in the CO2 price will not affect the steel and aluminium industries to the same extent. A price of 100 €/t of CO2 will affect the aluminium industry by about 13.8 % and the steel industry by 29.7 %. These are also competitive disadvantages, but relatively low when compared to the cement industry.

2 The Cembureau CO2 road-map 2050

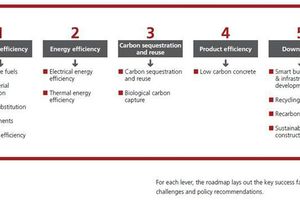

The cement industry has developed a vision of how the sector could reduce its emissions by 2050 [1]. In this roadmap by Cembureau, the European Cement Association, the focus is placed on five parallel routes that can each contribute to lowering emissions both in terms of cement and concrete production (Figure 5). The first three of these routes are considered to be under the control of the cement producers. Potential savings from the other two routes (Product Efficiency and Downstream) do not relate directly to cement manufacturing. Anyhow, the cement industry is committed to invest in innovation that explores new ways for cement and concrete to contribute to a low-carbon and circular economy.

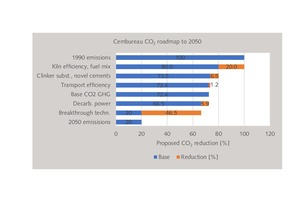

According to Cembureau, there is no single choice or technology that will lead to an 80 % reduction in emissions. Only a combination of different methods of emission reduction can achieve substantial reductions. Figure 6 shows the contribution of the different measures to the overall reduction, based on the 1990 emissions. Kiln efficiency, fuel mix and clinker substitution have already achieved some significant results and will contribute further until 2050, together with novel cements. Transport efficiency has a small effect of 1.2 %, if more water-ways and rail networks are used. The main assumptions are:

1. Same cement production quantity in 2050 and 1990

2. Average plant capacity will double to 5000 t/d

3. 60 % alternative fuels (of which 40 % is biomass)

4. Novel (low carbon) cements make up 5 % of production

5. 70 % clinker factor by 2050

The base CO2 of all of these measures will be still at about 72.4 % in 2050. Whether all the assumptions make sense is questionable. For instance, if the average plant capacity has to be doubled, then a large number of smaller plants will have to be closed or replaced by large kiln lines of 5000 to 6000 t/d by 2050, because very large kiln lines of 10000 t/d are not realistic in Europe. Furthermore, OneStone Research estimates that item 5 is underestimated, and that a clinker factor of < 60 % instead of 70 % would be more realistic. In 2011, the clinker factor in the EU was already 73.3 %, and in Germany the clinker factor was already 71.7 % in 2016. According to the IEA, China already had a clinker factor below 60 % in 2014 [2].

Using renewable power will have a small effect of nearly 6 % carbon reduction. But the main contribution to CO2 reduction is expected to be so-called breakthrough technologies, which will be responsible for the major part of 46.5 % in the CO2 reduction up to 2050. It makes sense to separate this sector into bridge technologies which are available on an industrial scale before 2030 and the ‘real’ breakthrough technologies which will probably not be available on an industrial scale before 2030. Furthermore, it is important to see which technologies are more suitable for retrofitting existing plants and which technologies are more suitable for new plants. Carbon capture technologies in the cement industry can be categorized by their ‘Technology Readiness Level’, with a scale of 1 (lowest level of technology readiness) to 9 (technology in its final form for cement kilns with > 1000 t/d) [3].

3 Bridge technologies (up to 2030)

3.1 Conventional technologies

ECRA, the European Cement Research Academy, published a recent report about the state-of-art techniques in cement manufacturing, covering mostly conventional technologies such as kiln efficiency, fuel mix and clinker substitution but also other carbon mitigation technologies [4]. In the ECRA report, the different technologies are discussed in detail. From our point of view, the conventional technologies play a major role in achieving the CO2 reduction targets by 2030. All these technologies are already used by almost all cement producers, and almost all technologies achieve significant savings in operational costs, while the adaptation of all other mitigation technologies will cost money.

3.2 Low-carbon clinker/cements

A large number of concepts developed by a number of cement producers are designed to substitute a small share of ordinary Portland cements by low-carbon clinker/cements. Such new binders include cements based on the carbonation of calcium-silicates, pre-hydrated calcium-silicates, belite cements, (belite) calcium sulfoaluminate clinker; metakaolin and others. However, from a mid-term perspective none of the new binding materials have the potential to replace cements based on Portland cement clinker on a larger scale. The new binding materials and systems presented will develop and enter the market for niche products with regional importance, e.g. for repair mortars, quick cements and other cementitious preparations [4]. A number of measures already taken are reported by the LCTPi [5].

3.3 Direct flue-gas use for CO2 storage and utilization

HeidelbergCement is one of the very few companies in the cement sector that for some years now have implemented projects to turn CO2 into valuable products [6]. One of the most interesting aspects is that in some of the projects cement flue gas is used directly, without any CO2 concentration. Such flue gas has CO2 concentrations below 30 % and in most cases around 13-15 %. One project started in collaboration with Oakbio in 2012 transfers CO2 into PHB biopolymer. Another project in collaboration with Joule Ltd was to use modified bacteria to convert CO2 into ethanol. Very promising is the use of CO2 for producing algae-based feed (Figure 7). Extensive work on the growth of micro-algae has been undertaken in three HeidelbergCement sites in Sweden, France and Turkey. Based on these findings, a commercial scale plant is now being installed in Morocco, benefitting from perfect climate conditions and the availability of large non-arable land plots.

Another technology which will suit the cement and aggregate industries is the use of CO2 from flue gas to carbonate (waste) minerals into building materials. Mineral carbonation is a chemical process in which magnesium and calcium silicates (e.g. serpentine, olivine, wollastonite) are reacted with CO2 to form stable carbonates. Industrial wastes (fly ash, cement kiln dust, blastfurnace slag) can also be used instead of natural minerals as starting materials for the production of e.g. lightweight aggregates. The advantage is that such processes use the unpurified exhaust gas to carbonate the minerals. However, the amount of CO2 that can be stored in such materials is relatively small.

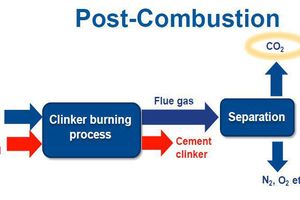

3.4 Post combustion technologies

Since May 2013, the European cement industry under the guidance of ECRA has conducted the first small-scale CO2 capture tests at the Brevik cement plant (Figure 8) of Norcem/Heidelberg-Cement. Post-combustion (Figure 9) is especially suited for cement plant retrofits. Three post combustion technologies have been tested, including solid sorbents (technology provider RTI Inter-national), amine scrubbing (technology provider Aker Solutions) and membranes (technology providers NTNU, Yodfat Engineers and DNV GL). Project information and test results are summarized in several papers [4, 7, 8]. As demonstrated by the tests from 2015-2016, amine-based technology (Figure 10) can be efficiently applied to capture CO2 from kiln flue gas. However, the tail-end separation of CO2 from flue gas is still energy-intensive. In 2017, the Norwegian government released funds via Gassnova for a full-scale amine scrubbing project to be studied in detail by Norcem and Aker Solutions as part of the complete carbon capture and storage chain.

4 Breakthrough technologies (from 2030)

Today, two breakthrough CO2 capture technologies are being discussed in the cement industry: Oxyfuel and Indirect Heating (Calix process). Although these technologies are now at the pilot stage, it is not expected that a full industrial size will be available before 2030. Anyhow, this is not only a matter of the technical development, economic support and costs for the technology implementation, but also depends on the emission allowances set by the government for the cement industry, the CO2 price of the ETS (EU Trading Scheme), the political and public pressure and last but not least, how much the net CO2 emissions per ton of cement have already been reduced by the cement producers with conventional methods.

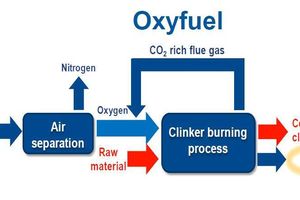

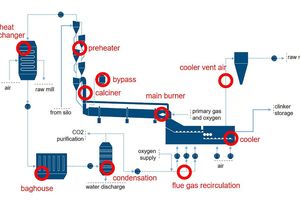

Oxyfuel technology (Figure 11) is currently seen as a more economic candidate for CO2 capture at cement kilns, although investment and operational costs are high. The use of O2 instead of air in kiln firing would result in a comparatively pure CO2 stream, which could be supplied to the transport and storage infrastructure with little effort for purification if it is a full oxyfuel system, and more effort if it is a partial oxyfuel process. The technology, which is also used in power plants, is able to concentrate the CO2 in the flue gas by recirculating part of the flue gas and feeding pure O2 to the burner to maintain the required burning conditions. The CEMCAP project aims to reach technology readiness level (TRL6) by investigating several issues (Figure 12) for oxyfuel technology in plant retrofits based on previous work by ECRA and Norcem.

In a next step, oxyfuel will be implemented in two cement plants in Europe. The Colleferro plant of HeidelbergCement in Italy as well as the Retznei plant of LafargeHolcim in Austria were chosen as demonstration plants. The advantage of the Colleferro plant (Figure 13) is that it has two kilns, of which one has not been operational and will provide optimal test conditions for industrial-scale operation to test for the first time how this carbon capture technology has to be adapted for a full oxyfuel process.

Based on opportunity studies and in-depth technical feasibility studies, the investment and costs for the test phase will amount to around € 80 million. While the cement industry has committed itself to contributing € 25 million, substantial funding from European or other research schemes will also be required.

HeidelbergCement and other companies have teamed up in a consortium with Australian technology provider Calix to develop a breakthrough calciner that can directly separate and capture the CO2 released from limestone when it is being transformed into clinker. The technology is called Leilac (Low Emissions Intensity Lime and Cement) and is now for the first time undergoing a test phase in the cement industry. The project at HeidelbergCement’s Lixhe cement plant (Figure 14) in Belgium includes design, construction and testing of the innovative indirect calciner. The € 21 million project at Lixhe plant has received € 12 million in support from the EU and will run for the next five years. This technology will open up tremendous opportunities: Integrated into the calcination process, the Calix reactor is capable of capturing almost pure CO2 released from the limestone. The technology offers added value, as it can capture these emissions without significant energy or capital expenditures.

5 Readiness of most promising technologies

ECRA’s carbon capture research and development started in 2007 in a long-term project designed to examine the capture of carbon dioxide as a prerequisite for a safe geological storage of CO2. However, since 2007 the priorities have changed and beside carbon storage the utilization of CO2 has also become an option. Accordingly, the utilization of CO2 for commercial purposes is now on the agenda. Without proper utilization, carbon capture projects are senseless. For CO2 utilization there are a larger number of options and possibilities [10]. The most promising include the use of CO2 as a chemical feedstock for the manufacturing of polymers, polyols and formic acid or for methane production or for power liquids including methanol, ethanal, isopropanol and biodiesel.

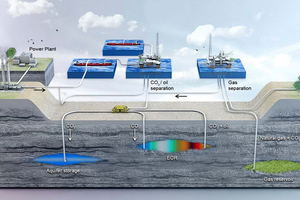

Up to now, CO2 storage has not achieved a breakthrough. The technologies and the complete supply chain from carbon capture, transportation and storage are available, as demonstrated e.g. by projects by Aker Solutions (Figure 15). But beside the oil & gas industries, which use CO2 for EOR (enhanced oil recovery), only a few other industries have been interested. With only two large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) power projects in operation at the end of 2017, with a combined capture capacity of 2.4 million t of CO2 per year, CCS in power remains well off track for achieving the SDS target of 350 million t per year by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

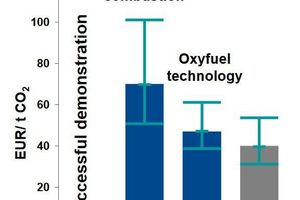

Today, the most promising carbon capture technologies include full oxyfuel systems and indirect heating (Calix) for new plants and several post-combustion technologies (amine scrubbing and calcium looping) and partial oxyfuel for plant retrofits. But there is still a very large variability and uncertainty in estimated investments and operating costs for these technologies. Table 1

shows investment costs for two options for a reference plant in Europe with 1.9 Mt/a clinker capacity (6000 t/d) and 2.7 Mt/a cement capacity. The reference price for a conventional state-of-the-art plant is given with € 260 million and 137 €/t clinker respectively. Figure 16 shows the estimated operational costs for these plants. Currently, the economic conditions would impair the competitiveness of cement production.

Technologies for carbon capture are at different levels of maturity and still have many hurdles to overcome. Post-combustion capture is expected to become commercially operational earlier (2020), then oxyfuel or Calix, which will need at least five years longer from today’s perspective (Figure 17). The figure is from a presentation in 2015, but has not changed very much.

6 Outlook

At the moment, the cement industry has no pressure to build cement plants which fulfill carbon capture requirements. There are a few global leaders such as HeidelbergCement, LafargeHolcim and Cemex, which are mainly involved in the CCUS research and development. One strategy is to implement projects which offer ‘quick wins’, even when they allow only a relatively small potential of CO2 abatement. Larger-scale projects are being systematically developed mostly in collaboration with technology developers, research institutes and other value chain partners. Probably it will take up to 2030 before the commercial-scale projects spread from Europe to the rest of the world.

//www.onestone.eu" target="_blank" >www.onestone.eu:www.onestone.eu

Überschrift Bezahlschranke (EN)

tab ZKG KOMBI EN

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

tab ZKG KOMBI Study test

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.

This is a trial offer for programming testing only. It does not entitle you to a valid subscription and is intended purely for testing purposes. Please do not follow this process.